2

Human Activity in Antarctica

Despite Antarctica's size, larger than the United States and Mexico combined, its very existence as a continent was not established definitely until the 1820s. It was 1899 before humans first wintered on antarctic shores and 1911 before Amundsen (and, shortly thereafter, Scott) reached the South Pole. Humans would not again set foot on the pole until 1956. Only in the 1930s, with expeditions such as those of Byrd and Ellsworth, did systematic and extensive scientific exploration of the region begin. Not until 1957 and 1958, during the first International Geophysical Year (IGY), did a science-oriented, international cooperative effort became a reality. Out of this effort arose the Antarctic Treaty that has been the focus for international scientific cooperation ever since.

Excepting the exploitation of seals and whales, human activities have left few long-term marks in the Antarctic Treaty area. Expeditions and long-term bases clearly have caused local disturbances in the past, but the current emphasis is on cleaning up past problems and paying more attention to environmental concerns associated with activities in Antarctica.

In recent years, the world political and social climate has caused human activity in the antarctic region to rise sharply, primarily for two reasons: (1) nations that historically were not involved in antarctic exploration have sought representation in the antarctic community and have established scientific bases so that they may participate; and (2) private citizens, in increasing numbers, have visited the Antarctic as tourists to enjoy the continent's pristine and aesthetically pleasing environment and the spirit of adventure deriving from the remoteness of Antarctica. Human activities that may have environmental consequences in the Antarctic have been well documented by several authors, most notably Benninghoff and Bonner (1985), who detailed the types of impacts caused by human activity and suggested ways to evaluate them in a scientific framework. This chapter briefly discusses such activities and their implications for scientific programs under the Protocol on Environmental Protection.

PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

Antarctica is covered mostly by ice. The transition zone between the continent and the surrounding seas is the site of unique climatic regimes. Extremely strong offshore katabatic winds are caused by the descent of cold air masses from the interior of the continent. The changes in relative durations of daylight and dark are also extreme—24 hours of darkness in winter change to 24 hours of daylight in summer. The seas surrounding the continent freeze during the winter and melt during the summer. This freezing and melting creates a dynamic physical environment and contribute to the rich nutrient loads in the surrounding waters.

The harshness of the antarctic environment is extremely taxing on human endeavors. The journals of the early explorers contain graphic descriptions of the antarctic climate. One of the most famous of these explorers, Captain Robert F. Scott, walked with four companions pulling sleds to the South Pole, arriving on January 18,1912. They perished returning from the pole, but left detailed accounts of the hardships of the trek. On the return, for example, on January 19, 1913, at an altitude of 2,960 meters, the minimum temperature was-32°C. As they continued their trek toward the coast in the bitter cold, one entry reads, ''cold night, minimum temperature minus 37 degrees'' (Scott, 1913). Later, on March 2, Scott's journal reads, "it's down to minus 40 degrees and this morning it took one and one-half hours to get our foot gear on, but we got away before eight" (Scott, 1913). Because of the harshness of the antarctic climate, any scientific or other operations in the region require special equipment and facilities. In order to reduce the requirements for human presence, some research activities are now trending toward the use of remote, untended facilities for scientific measurements and investigations, as illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Marine temperatures in the region are less severe than over the antarctic land mass. During the winter, when sea ice is present and darkness prevails, it is extremely cold, but as spring arrives and the sea ice melts, temperatures rise and human activities become quite feasible. Even in the austral summer, however, ice-strengthened research ships are a necessity. In addition, standard gear for sampling the marine environment must be modified to prevent damage by persistent sea ice. Investigators must employ specialized and innovative techniques, such as use of moored arrays of instruments below the sea ice to collect oceanographic data. Data acquisition systems using satellite links are also very useful in this region. Even scientists working in the marine environment where temperatures are less extreme must cope with a unique climate that requires special modification of personal activities and scientific instrumentation.

Perhaps the most telling reflection on conditions in Antarctica was written by Scott, apparently in frustration when his party learned that

FIGURE 2.1 The first Automatic Geophysical Observatory (AGO) set up for unmanned operations at a remote site in Antarctica 500 km from the South Pole. The ski-equipped Hercules aircraft is positioned to deliver the year's supply of propane that fuels the AGO's 60 watt thermoelectric generator. Heat from the generator is used to maintain the shelter at a constant room temperature while the experiment electronics pass nearly 3 gigabytes of science data to the AGO's recorders. Six instruments supplied by one Japanese and five U.S. institutions are included in the instrument complement for studies of upper atmosphere physics. Also included is a set of meteorology instruments. (Courtesy of J.H. Doolittle, Lockheed Palo Alto Research & Development Laboratory. Acknowledgement: NSF/OPP contract DPP 88-14294).

Norwegian explorers had reached the South Pole before them: "Great God, this is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have labored to it without the reward of priority" (Scott, 1913). No doubt, even today, many antarctic scientists attempting outdoor activities that do not go according to plan have felt these same frustrations. The harshness of the antarctic environment imposes an extra measure of difficulty on everyone who works or visits there. People inexperienced with these conditions quickly learn that additional time and effort are required to accomplish even seemingly simple tasks.

HUMAN ACTIVITY

Although research activities—first exploratory and today more broadly focused on a range of scientific frontiers—have been the predominant human activity in Antarctica for nearly half a century, this has not always been the case. Antarctic waters supported a substantial whaling and sealing industry during the 19th and 20th centuries. Although whaling and sealing are not now done, these waters still support commercial fishing for a variety of species. Perhaps the most notable change in use of the Antarctic is the significant increase in numbers of tourists visiting the continent in recent years.

Exploration, Research, and Resources

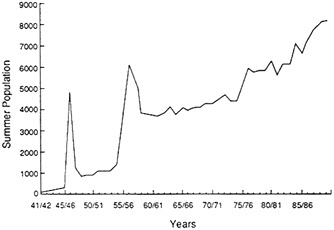

Aside from the expeditions of the early 1900s, continuing human activity in Antarctica began in the early 1940s, with people of several nations overwintering yearly. Beltramino (1993) has compiled data on the numbers of stations and summer and overwintering personnel through 1990. Figure 2.2 shows the summer population of Antarctica beginning in 1942; it shows a sharp rise in 1946, followed by a drop until 1957 when the IGY began. Between 1946 and 1990, the number of stations operating in Antarctica grew from 6 to 40.

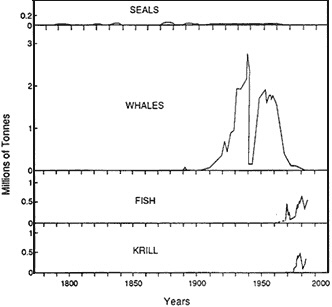

Since the early 1800s humans have exploited various species that inhabit the antarctic seas. Exploitation of fur seals and elephant seals began in the early 1800s and continued until 1960. Just before 1900, antarctic whaling became a very large, worldwide industry and, excepting the years of World War II, continued into the mid-1980s. Whale populations by then had dropped to extremely low numbers; under pressure from public opinion, the International Whaling Commission declared a moratorium on the commercial take of whales. Particularly in the Antarctic Peninsula region, many beaches, especially those close to whale processing facilities or anchorages used by whaling vessels, contain large whale bones as mute testimony to this past activity. In recent times, antarctic fish and krill have become more important commercially. Figure 2.3 shows trends in the take of seals, whales, fish, and krill since the beginning of the various commercial efforts.

The antarctic seas are far from untouched. Their biological resources have been harvested extensively, and several species have been substantially depleted. This harvesting is likely to continue, particularly if krill becomes an important source of protein for humans and/or other uses. The take of fish and krill is now regulated under the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR). Under CCAMLR, regulations and management actions have been developed for some fish species. However, even as the marine system is recovering from past exploitation,

the possibility of commercial exploitation of new species, such as crab, arises. Studies of the recovery of depleted populations will provide interesting insight into ecosystem dynamics. Ecologists studying the recovery of the whales, for example, will watch carefully to determine what effect this recovery might have on other species competing for krill.

Tourism

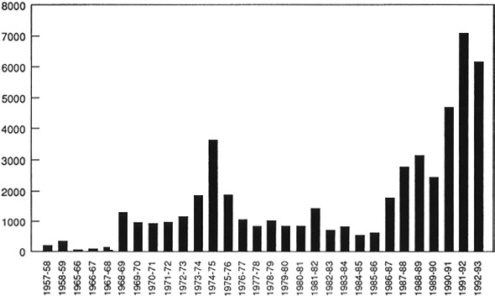

Antarctica holds a special fascination for people wishing to see its rich and diverse wildlife, vast scenic beauty, massive glaciers, icebergs and ice shelves, and the historic huts and sites of the pioneering explorers. Commercial tourism is relatively new to Antarctica; development of the industry has been well documented by several authors, including the historians Reich (1980), Headland (1989), Enzenbacher (1992), and Stonehouse (1992). The first recorded tourists flew over the continent in 1956. In the 1957–58 season, Chile and Argentina took more than 500 fare-paying passengers to the South Shetland Islands by ship. Since then, antarctic tourists have traveled primarily by ship, although a small number have also flown to the interior of the continent for activities including mountain climbing, skiing, wildlife photography, and dogsledding. What began in the late 1950s with a small number of ships and tourists has increased to more than 50 voyages during the 1992–93 season by seven U.S.-based tour companies and three foreign companies, carrying an estimated 6,166 fare-paying passengers (N. Kennedy, National Science Foundation, personal communication, 1993). The 1992–93 season saw the widest range of vessels used to date, including private yachts, ice-strengthened expedition ships, nonstrengthened cruise ships, and icebreakers. Tourists are no longer just visiting the Antarctic Peninsula and nearby offshore islands; ships are now taking them to the Ross Sea, Adelie Land, and other coastal areas as far west as Mawson Station. One ship during the 1992–93 season took tourists by helicopter to the Dry Valleys, west of McMurdo Sound (see Figure 1.1), and at least one tour ship plans voyages in the Weddell Sea during the 1993–94 season.

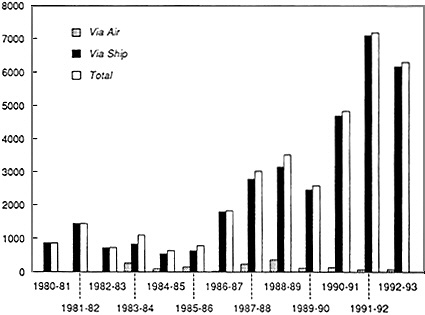

Although, as shown in Figures 2.4 and 2.5, tourism has grown from year to year, especially since 1986, in the 35 years since tourists first visited Antarctica, the total number is still smaller than the crowd at one football game of a major university. Since the 1991–92 season, it is estimated that tourists visiting the continent annually have outnumbered the personnel involved in national scientific and logistic programs in the area covered by the Antarctic Treaty System (Enzenbacher, 1992). Because tourism is nearly all ship-based, however, tourists' time on land is less than 1 percent of that of scientific and support personnel (J. Splettstoesser, International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators, personal communication, 1993).

Airborne tourism has only added slightly to the total counts of tourists-more than 90 percent of them have visited Antarctica by ships (Enzenbacher, 1992; and Stonehouse, 1992). The first tourist flight to Antarctica was arranged by a Chilean national airline. The flight in a Douglas DC-6B took place December 22,1956; 66 tourists made the trip (Headland, 1989). Pan American Airways operated the first commercial Stratocruiser flight to land at McMurdo Sound in October 1957 (Headland, 1989). Overflying without landing, or flight-seeing, became popular in the 1970s, when planeloads of tourists were flown over the continent at low altitude by both Qantas Airways and Air New Zealand. Between February 1977 and December 1980, 44 flights, involving more than 11,000 passengers, were operated (Reich, 1980). Flight-seeing, for all practical purposes, came to an end following the crash of an Air New Zealand DC-10 on Mt. Erebus in November 1979. All 257 passengers and crew were killed.

In the 1983–84 season, the Chileans began operating C-130 flights, carrying 40 passengers, from Punta Arenas to Teniente Rodolfo Marsh Station on King George Island. Hotel accommodations are available at Estrella Polar,

FIGURE 2.4 Estimated numbers of shipborne and airborne tourists having visited Antarctica from 1980–81 to 1992–93. Sources: Enzenbacher (1992), National Science Foundation (1992a), N. Kennedy, National Science Foundation, personal communication (1993).

the first hotel in Antarctica. Small ski-equipped aircraft are also being used to fly passengers to the Antarctic. Since 1984, the dominant company has been Adventure Network International. This organization takes expeditioners, photographers, and mountain climbers to many inland destinations, including the geographical South Pole and the highest mountain peaks in Antarctica. These flights, primarily in DC-6s and Twin Otters, are operated mostly during the austral summer. However, during the 1989–90 season, nine months of operation (July to April) were reported (Swithinbank, 1990).

In an effort to manage the growing tourism industry, in 1989 three major ship tour operators developed two sets of guidelines: Guidelines of Conduct for Antarctica Visitors and Guidelines of Conduct for Antarctica Tour Operators. These guidelines formalized existing shipboard practices for ensuring that tourism is environmentally friendly to promote conservation in Antarctica. The guidelines are reviewed annually and updated as necessary. During the 1992–93 season they were used by 13 companies, both U.S.-and foreign-based, that conduct ship and airborne travel to Antarctica.

The Guidelines of Conduct for Antarctica Visitors is used to educate travelers about their responsibilities under the Antarctic Conservation Act, behavior around wildlife (including recommended distances of approach), and the need to protect the flora, fauna, historic relics, and sites of Antarctica. The guidelines also inform travelers that visits to Specially Protected Areas (SPAs) and Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), and interference with scientific projects are prohibited, and that tourists may take from Antarctica only photographs and memories. Most companies now feature all or part of these recommendations in their advertising brochures and provide the full text of the guidelines in pretour mailings to passengers. Before arrival in Antarctica, passengers on board are briefed on the guidelines by the expedition leaders. In the field, staff and naturalists monitor passenger behavior.

The Guidelines of Conduct for Antarctica Tour Operators focus specifically on vessel operations and the duties of the crew and staff in ensuring that the program is operated responsibly. Comparable guidelines have been adopted by Adventure Network International to formalize existing practices in its airborne and land-based operations. The full text of the Guidelines of Conduct for Visitors and Tour Operators is included in Appendix A.

EFFECTS OF HUMAN ACTIVITY ON SCIENCE

Any human activity in Antarctica has some form of impact on the environment. One of the major categories of human activity is the establishment and operation of research stations, airstrips, and other facilities needed to support scientific work. Historically, the impacts of these types of activities were not thought to be potentially important. Attitudes toward the environ-

ment have evolved, however, and scientific and logistic activities today will require closer monitoring for potential environmental impacts. This new focus requires additional justification for scientific facilities and closer examination of the need for given scientific programs. Future scientific and logistic activities in Antarctica will aim for less environmental disturbance; concomitantly, scientific measurements and studies will be less affected by such disturbances.

The degree of environmental disturbance varies with the science involved and with the specific project. Most scientific activities involve little disturbance. However, certain programs require remote measurement devices, which potentially can be lost and released into the antarctic environment; other experimental work may require the collection of specimens or the release of chemicals. Such scientific programs are important to the understanding of antarctic systems and are likely to be significantly affected by the implementation of the Protocol. The implementation process, therefore, should seek to balance the potentials of scientific gain and environmental impact.

The impact of commercial fisheries on the antarctic marine ecosystem is a major concern. Commercial fisheries have already overexploited certain finfish populations. Under CCAMLR, many scientific programs contribute data that are useful in regulating commercial fishing activities, but unrelated research programs may be affected by commercial fishing. One example is basic studies of the life history of antarctic krill (Euphausia superba). Fishing, although monitored and regulated under the auspices of CCAMLR, seems to have an uncertain policy link to the Environmental Protocol. The Protocol covers all human activities that have environmental impacts, but its primary concern is with scientific programs and tourism. It seems likely that commercial fishing activities will influence scientific programs in the marine system and perhaps those in coastal regions as well. Effective coordination between CCAMLR and the Protocol seems essential and demands further examination.

The extent of impact from tourists is not known because the baseline data and conclusive monitoring programs are as yet incomplete. Potential impacts include disturbance of flora and fauna, disruption of scientific activities, and marine pollution by vessels and small boats. The crash of the Air New Zealand DC-10 on Mt. Erebus and several ship groundings have illustrated the dangers of operating in Antarctica.