Health Policy Issues in Three Latin American Countries: Implications of the Epidemiological Transition

José Luis Bobadilla and Cristina de A.Possas

Even in middle-income countries, more favorable statistics in the aggregate disguise wide disparities between the conditions, on the one hand, of the rural and peri-urban poor that are typical of low-income countries and the conditions, on the other hand, of more affluent urban dwellers who are better educated and have better access to health services and whose health status closely resembles the profile in industrialized countries.

John Evans et al. (1981)

INTRODUCTION

This paper is concerned with health policy issues in Latin American countries, with emphasis on the changes that health systems need to introduce to meet the health needs resulting from the demographic and epidemiological transitions. To illustrate these policy issues, three country cases are analyzed here: Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico. The population of these

J.L.Bobadilla is Health Policy Specialist, Population, Health, and Nutrition Division, The World Bank. C. Possas is with the Department of Administration and Planning, National School of Public Health Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Brazil. The authors wish to thank Juan Eduardo Cespedes for information and comments on the current health situation in Colombia and Richard Cash, Xavior Coll, Oscar Echeverri, James Gribble, and Samuel Preston for comments.

countries includes about 60 percent of the population of Latin America. These three countries are now facing an important decline in mortality and fertility rates, and new sets of health problems that are related to rapid urbanization and industrialization, such as injuries, accidental intoxications and poisoning, and occupational and noncommunicable diseases affecting an aging population. At the same time, old health problems have not yet been solved; these countries are not yet free of the burden of many infectious and parasitic diseases, although their overall mortality rates for infectious diseases are declining. Analysis of the distribution of both groups of diseases shows wide disparities in health conditions across different regions and social classes.

The coexistence of old and new health problems and the persistence of wide social disparities in these developing Latin American countries have been described before (Evans et al., 1981) and referred to by Frenk et al. (1989) as “epidemiological polarization” and by Possas (1989a) as “structural heterogeneity.” These authors have stressed the importance of identifying the main consequences of this complex transitional process in developing countries. The increasing burden of chronic diseases affecting a growing adult population in these Latin American societies will be, in the next decades, an important challenge to their governments because many of their old, unsolved health problems are likely to persist. This epidemiological diversity and the rate of change in the disease profiles make the health transition process in many developing countries much more complex than the situation faced now, or before, by developed societies (Evans et al., 1981). Developing countries are reducing their fertility rates and their mortality rates due to infectious diseases in shorter periods than industrialized countries, leaving a much shorter time to adjust the health system to respond adequately to the needs of adults and the elderly and, at the same time, maintain efforts to reduce the burden of infectious diseases in children and reproductive health problems. Two other factors differ between developing and industrialized countries: first, most developing countries still lack the required health infrastructure to deal with the most pressing health needs of their populations, and to judge from their gross national products and the proportions spent on health, this situation is not likely to improve in the near future; second, most governments of developing countries are being pressed to adopt the therapeutic medical model to deal with the burden of noncommunicable diseases.

The current health care paradigms for developing countries, characterized by the primary health care model, have been effective in dealing with epidemiological scenarios in which infection and reproductive health problems dominate. It is not clear how governments should reorient their health systems to respond to the new challenges posed by population aging and the emergence of noncommunicable diseases. This paper reviews the main

policy issues that should be considered in reorienting the health system, in light of the epidemiological transition.

Recent analyses of the epidemiological transition (Caldwell et al., 1989; Laurenti, 1990; Jamison and Mosley, 1991; Frenk et al., 1991; Bell, 1993; Possas, 1991) suggest that the understanding of its policy implications can contribute to highlighting important aspects of the existing theoretical framework related to the health of human populations. Understanding the process of policy formulation in heterogeneous developing societies passing through the epidemiological transition can help to develop new concepts and methodologies for health care planning.

The formulation of policies in the health sector is influenced by various elements that interact with the epidemiological transition. The conceptual model presented in the following section briefly describes the main elements that influence health policy formulation and indicates the most relevant relationships. Next, basic information is presented on the socioeconomic, demographic, and health characteristics of the population and the health system organization in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico. In the following section, critical policy issues are described and discussed with a focus on how they are affected by the epidemiological transition.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR EXAMINATION OF POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The underlying causes of long-term changes in epidemiological profiles are not clearly understood. Our limited comprehension of the proximate determinants of health status suggests that changes in the standards of living, lifestyles, access to and quality of health services, and nutrition account for most of the improvements in survival in contemporary societies (Frenk et al., 1991). The technological advances in prevention and treatment of common diseases occurring in the past 50 years have changed the relative importance of these factors. A result is that now some countries with low income per capita ($300) are able to reduce substantially the burden of infectious and parasitic diseases. Thus, health policies in developing countries are addressing an increasingly broader set of issues related to the health status of populations.

Many of the policy issues that governments need to consider when dealing with the consequences of the epidemiological transition are country specific. The factors that determine the health status of the population, and the organization and performance of the health system, need to be taken into account. In this section, we briefly review these factors. Rather than presenting a comprehensive list of these determinants, we highlight those that are likely to play a relevant role in health policy formulation in the three selected countries.

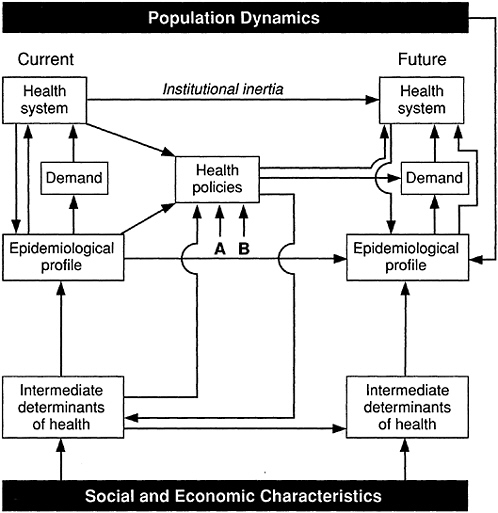

The main determinants of health policy and their interrelationships are summarized in Figure 1. It is essential to understand the population dynamics; size and distribution of the population provide a first idea of the magnitude of health needs. The rate of population growth and the process of population aging are the most important variables to be considered. Within a country, intense rural-urban migration often poses additional burdens on the local health systems of big cities.

The contribution of fertility decline to the aging of populations and changing mortality levels and profiles have been described elsewhere (Bobadilla et al., 1993; Jamison and Mosley, 1991). It is worth mentioning that these demographic factors may play a far more relevant role in the epidemiologi-

FIGURE 1 Principal determinants of health policy: (A) legal frame, (B) role of the state with regard to social needs.

cal transition than changes in the risk factors for noncommunicable diseases. Nevertheless, the paucity of information on the prevalence and trends of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases in developing countries, including the three analyzed here, precludes any definite statement on their relevance in the forthcoming decades.

The current status of the health system can be described by multiple variables such as number of institutions, coverage of different services, mix of private and public sources and amount of financial resources, efficiency, equity in the distribution of resources, and quality of care. Organizational and performance deficiencies of the health system are common in many countries of the world and obviously need to be corrected before other policies designed to respond to the epidemiological transition can be implemented. Most governments allocate resources in the health sector according to the pattern of expenditure of previous years, creating an institutional inertia to maintain the status quo in their health systems. This inertia reduces the flexibility of the health system to adapt to new challenges, such as those posed by the epidemiological transition.

As Figure 1 illustrates, the current health system is related, in part, to the epidemiological profile, because it is supposed to control, prevent, and treat the main diseases and injuries. However, the health system is also determined by other social and economic factors, such as the market forces of drugs and medical equipment, technological innovation in diagnosis and treatment, the medical labor market, and political interests. Future health policies should ideally be oriented toward improving the capacity of the health system to respond to the changing demand due to the epidemiological transition.

The relationship between the epidemiological profile and the health system is depicted in Figure 1 as occurring directly and mediated through demand. Some health needs of the population elicit direct responses from the health system, as is the case with immunization. Others, such as case management of noncommunicable diseases, are identified through demands from the population. Needs and demands are clearly not synonymous, because demand depends on the health status and the perception of illness by individuals and families. Perceptions are a critical element to consider in health planning because a large proportion of the rise in demand for health care is due to an increase in illness perception and not necessarily to higher prevalence of disease.

Health policy options are also affected by two other factors that are often ignored because they are resistant to change. These are the legal framework for health, environment, and health care; and the ideological standpoint that governments and leading population groups hold regarding health and the role of the state in the provision of health services. These two factors often limit the options available in the formulation of policies.

They can, of course, be changed and often are objects of policy. Because they are country specific, it is difficult to generalize about the restrictions they impose on health policy alternatives.

HEALTH POLICY IN BRAZIL, COLOMBIA, AND MEXICO

This section describes, for Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, the most important elements of the conceptual framework described in the previous section.

Social and Economic Characteristics

Wide disparities can be observed in economic factors such as gross national product (GNP) per capita, which ranges from U.S. $1,200 in Colombia to U.S. $2,540 in Brazil, and average annual inflation, which ranges from less than 24 percent in Colombia to more than 200 percent in Brazil, as shown in the appendix. Nevertheless, all three countries share similar patterns of income concentration, with about 40 percent of income in the highest 10 percent income group and from 1 to 4 percent of income in the lowest 20 percent income group.

Social conditions also show similarities and disparities. All three countries share similar proportions of population in poverty ranging from 37 percent in Mexico to 45 percent in Brazil, but other social conditions, such as access to potable water, sanitation facilities, and education, are quite different. In Brazil, there is a very high illiteracy rate (22 percent of adult population), whereas in Colombia and Mexico these rates are 12 and 10 percent, respectively. In Mexico, access to safe water is limited to 69 percent and access to sanitation facilities is 45 percent, whereas in Brazil and Colombia at least 75 percent of the populations have access to piped water and more that 65 percent have access to adequate sanitation facilities.

Finally, it is interesting to note that even though Colombia has the lowest GNP per capita, its social and health indicators are not far below those of Mexico and Brazil. For some indicators, such as under-5 mortality and life expectancy, Colombia is in a better or similar position. Investments in prevention and primary health care in Brazil and Mexico have been relatively small in the past three decades, and only in the mid-1980s did this situation start to change. Colombia, on the contrary, has concentrated national efforts on population-based activities to control communicable diseases.

Population Dynamics

In the past 30 years, the three countries have experienced substantial reductions in their total fertility rate, giving rise to a profound change in the

TABLE 1 Population Dynamics in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, Selected Years

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age Structure (%) |

|||

|

Country |

1989 Population (millions) |

Total Fertility Rate |

1989 |

2025 |

||||

|

1965 |

1989 |

2000 |

0–14 |

15–64 |

0–14 |

15–64 |

||

|

Brazil |

147 |

5.6 |

3.3 |

2.4 |

36 |

60 |

23 |

67 |

|

Colombia |

32 |

6.5 |

2.9 |

2.2 |

36 |

60 |

22 |

68 |

|

Mexico |

85 |

6.7 |

3.4 |

2.4 |

38 |

58 |

23 |

68 |

|

SOURCE: World Bank (1991: Table 32). |

||||||||

age structure of their populations. Table 1 shows the total fertility rate estimated for the years 1965 and 1989, and projected for the year 2000. From levels between 5.6 and 6.7 children per woman, total fertility dropped to about 3.0 and is estimated to be around 2.2 by the year 2000. This decline has been achieved to a large extent as a consequence of the greater contraceptive use by women of reproductive age, which in 1987 reached levels of 53 percent in Mexico, 63 percent in Colombia, and 65 percent in Brazil. The main change in the population structure is an important growth in the proportion of the population age 15 and over. By the year 2025 almost 70 percent of the population of these countries will be 15 to 64 years old.

Health Status

The health status of the populations of Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, according to information on mortality levels, has improved considerably over the past 60 years. Currently, life expectancy at birth is 69 years for Mexico and Colombia and 66 years in Brazil. The childhood mortality rates are lower for Colombia and Mexico (50 and 51 per 1,000 children under 5, respectively) than for Brazil (85 per 1,000), as shown in the appendix. Although these indicators show a considerably better health status than many developing countries, they are quite unsatisfactory when compared with countries that have similar or lower annual income per capita such as Costa Rica and Chile.

The epidemiological profile of the three countries shows that according to mortality statistics, infectious and parasitic diseases are no longer responsible for the majority of deaths. Rather cardiovascular disease, cancer, and injury explain between 44 and 59 percent of total deaths, as shown in Table 2. Mexico has a larger share of deaths due to infectious and parasitic diseases and malnutrition, and Colombia has more deaths due to injury.

TABLE 2 Distribution of Deaths by Causes of Death in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico Around 1986

|

|

Country (%) |

||

|

Causes of Death |

Colombia (1986)c |

Mexico (1986)b |

|

|

Infectious and parasitic diseases, and malnutrition |

12 |

12 |

20 |

|

Perinatal and maternal causes |

7 |

6 |

7 |

|

Injury and violence |

11 |

19 |

16 |

|

Cardiovascular disease |

28 |

27 |

19 |

|

Cancer |

9 |

13 |

9 |

|

Other |

12 |

19 |

26 |

|

Ill defined and senility |

21 |

4d |

3 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Total of registered deaths |

(787,341) |

(146,400) |

(396,565) |

|

aData for Brazil include only some reporting areas that concentrate on the more developed parts of the country. Therefore, figures underestimate the share of deaths due to infectious diseases and overestimate the deaths due to noncommunicable diseases. bWorld Health Organization (1990). cMinisterio de Salud (1990). dOnly ill defined. |

|||

The coverage of mortality statistics in Brazil is less than in the other two countries; thus the information in Table 2 probably underestimates the number of deaths due to infectious and parasitic diseases in Brazil.

To understand better the heterogeneity in epidemiological profiles, health status indicators at the national level need to be stratified by socioeconomic variables. Table 3 shows childhood mortality rates according to different levels of the mother’s education. The childhood mortality rates among children whose mothers are less educated are between three and four times greater than those for children whose mothers have the highest educational level.

Main Characteristics of Health Systems

Organizational Structure

Health systems in the three countries have different organizational structures. In Brazil, government and social security agencies have been integrated into the Unified Health System, but in Mexico and Colombia, there is a clear division of responsibilities between the ministries of health and the social security agencies. The responsibilities differ in the two countries: in Colombia, the Ministry of Health provides the majority of health services to

TABLE 3 Mortality Rates (per 1,000 population) for Children Under 5, According to Formal Education of Mother—Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico

|

|

Country |

||

|

Mother’s Education |

Brazil (1978–1986) |

Colombia (1978–1986) |

Mexico (1979–1987) |

|

None |

136 |

78 |

112 |

|

1–3 years |

137 |

65 |

91 |

|

4–6 years |

70 |

40 |

54 |

|

7–11 years |

40 |

25 |

29 |

|

Ratio of highest to lowest rate |

3.4 |

3.1 |

3.9 |

|

SOURCE: Rutstein (1992: Table 3). |

|||

the population and the Social Security Institute covers only a small proportion of the population active in the labor force. In contrast, in Mexico, the Ministry of Health concentrates its services on the poor, and social security agencies cover about 60 percent of the total population.

The size and role of the private sector are also quite different in the three countries. In Brazil the private sector is very large and provides services to the unified public system. Private insurance plans are also growing very fast. In Colombia and Mexico the private sector also plays an important role, but there is no significant provision of private services funded by the public system. The insurance plans in these countries are also growing, but their sizes are very small.

Source of Finance

The sources of finance follow the organizational structures in the three countries. In Mexico and Colombia, where a clear division between the social security institutes and the ministries of health exists, the services of the former are financed through contributions from employers and employees, and of the latter through general taxation and fees. Colombia also obtains funds through earmarked taxation of specific products (such as beer or tobacco) to finance specific components of the health services. Brazil, on the other hand, integrates these different sources into a single health fund to finance its Unified Health System.

Coverage

Despite the relatively high income per capita of these three countries (within the context of developing countries), there is evidence to suggest

that 20–30 percent of the population have not access to basic health services. The coverage of deliveries attended by health professionals range from 70 percent in Mexico to 81 percent in Brazil, and immunization of children receiving the third dose of the diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus vaccine varies from 66 percent in Mexico to 87 percent in Colombia (United Nations Children’s Fund, 1992).

Distribution of Resources

Health conditions in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico have improved considerably for the majority of their populations during the recent decades. Unfortunately, the uneven distribution of social benefits derived from development has accentuated health inequalities. The current organization of health services widens existing health inequalities in the three countries analyzed here, mainly because the distribution of resources is biased toward the middle and upper classes, and the quality of care, for those who have access, is generally inversely related to socioeconomic status (Bobadilla, 1988).

Decentralization of Health Services

The three countries analyzed here underwent a very intense decentralization process in their health systems during the 1980s. This process was a consequence of two main determinants: the growing political pressure for the empowerment of local levels and the need to increase the flexibility of the health systems, making them more adequate to the growing diversity in epidemiological profiles and local realities (Rondinelli and Cheema, 1983). Analysis of the decentralization experiences in these countries indicates that this process seems, in general, to constitute a positive response to the social changes and increasing epidemiological diversity. However, a major problem for local governments and communities in this process, especially in poorer areas and regions, has been the lack of managerial capacity and instruments at the local level to deal with the new duties and attributions transferred in decentralization (Vianna et al., 1990).

The information presented in this section indicates that the three countries analyzed are relatively similar in their demographic and health profiles, but exhibit large disparities in the organization and delivery of health services. The reforms, still in process in the three countries, are all oriented in the same general directions: greater unification of health institutions, more decentralization of operations, greater responsibility of the government to finance health care, and sustained commitment to expand the coverage of services and strengthen the primary level of care. It is also difficult to assess the effectiveness of health policies that are implemented by other

sectors of the economy: water and sanitation, pollution control, food distribution and safety, tobacco taxation, road safety, etc. Ministries of health in these countries express concern over these intersectoral policies but generally assign lower priority to these issues compared to the provision of health services. Even health programs that fall into their domain, but are not related to health care, such as sanitary regulation or health education, tend to receive lower priority. This outcome is due in part to the low level of expenditure in social sectors and the relative weakness of the ministries of health to enforce laws and regulations, and to lead other ministries to undertake intersectoral policies.

HEALTH POLICY ISSUES AND OPTIONS

Analysis of the complex epidemiological transition process in these three Latin American countries suggests that it is not possible to formulate a homogeneous health policy agenda for developing countries. The health problems faced by the middle-income countries need to be addressed differently from those of low-income countries where infectious diseases and undernutrition still clearly predominate. In spite of this need for specificity in the analysis of each country case, we have identified a set of issues that should orient health planning strategy. The discussion of each issue illustrates the complexities involved in reshaping the health system so that it is more responsive to demographic and epidemiological changes, and also serves as a guide to analyzing policy options in other developing countries.

Provision of Health Services as a Means to Redistribute Welfare

Inequalities in health status are the consequence, in large part, of concentration of income and other goods and services. According to the social justice objectives declared by the governments of the three countries studied here, social services, including health services, should contribute to the redistribution of the benefits of development. In these three countries, the health system fails to do so and, in some situations, exacerbates inequalities (Médici, 1989; Bobadilla et al., 1988). Five systemic policies are proposed to achieve greater equity in the distribution of health services.

Change in Eligibility Criteria for Access to Health Services

The partial coverage of social security in Colombia and Mexico shows regressive effects in the distribution of welfare because the financing of the system is supported by the whole society, but the benefits are restricted to the middle and lower-middle classes. By eliminating the barrier to social security for the unemployed, peasants, and workers in the informal sector

(largely self-employed), greater equity in the distribution of resources by socioeconomic groups could be achieved. Incorporation into the Brazilian Constitution of the notion that social security should be universally accessible and distinguished from the more restricted notion of seguro social, which limits access on the basis of employment, is an example of the legal steps that can be taken toward this policy.

Tax Reform

A tax reform that eliminates differential health subsidies for the middle and upper classes could contribute to greater equity in health services. Medical expenses and drugs are tax deductible in the three countries. The net result is that the middle and upper classes benefit because they are more likely to earn enough to pay taxes, and they consume the vast majority of private health services (Cruz et al., 1991). The lower-middle class and some groups of the poor live with low cash income and also utilize private health services, but have no means of recovering their expenditure. In addition, most of the population groups that have no access to health care are in extreme poverty. This type of tax policy, intended to provide incentives for the utilization of health services, produces a regressive effect in the distribution of welfare.

Ration or Eliminate Health Interventions of Low Cost-Effectiveness

Implementing a policy in the public sector to limit health interventions that are not cost-effective is justified in all circumstances because health needs are infinite and resources are not. Its importance should be stressed now because the current trend in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico is to reproduce the therapeutic component of the health care model for noncommunicable diseases, as is done in industrialized countries. Most of the technologies and interventions available to treat the most common chronic and degenerative diseases are extremely expensive and relatively ineffective (Jamison and Mosley, 1991). The proposed policy would free scarce resources that can be used to finance the next two proposed policies, which require additional investment.

Expand Coverage of Public Health Services for the Poor

Expansion of public health services for the poor is already a policy in the three countries analyzed here. The problem is that the poorest segments of the population have not been reached. Brazil and Mexico face serious difficulties in reaching rural areas due to long distances and lack of transport and of other goods and services in these communities. Many rural

communities are very small (Mexico has more than 100,000 communities with fewer than 500 inhabitants), making investment in these communities not very cost-effective. On the other hand, in communities where transportation is readily available, potential still exists for increasing coverage. Successful models that use community health workers to reach the rural communities in the three countries should be replicated and the scope of their activities reviewed to assess their abilities to prevent noncommunicable diseases.

The financial feasibility of extending coverage to all the poor who lack access to health care needs to be carefully reviewed. If the current allocation of resources (by health programs) is maintained and extension depends exclusively on new funds, this proposal is not feasible in the next decade or so. As mentioned earlier, waste derives from inefficiencies and application of non-cost-effective interventions. There is evidence to suggest that the current human and financial resources in Brazil and Mexico would clearly be sufficient to extend coverage to all the poor unserved communities just by improving the efficiency and rationalizing the allocation of resources for health programs. The political and technical feasibility of designing and implementing these reforms is difficult to assess, but given the major macroreforms already implemented in Mexico and Brazil, this policy seems to be feasible.

Reduce Differences in Quality of Care between Health Agencies

Equalizing quality of care is necessary regardless of the implications of the epidemiological transition, because of the low standards of care prevailing in many health institutions in these countries (Gish, 1988). The equity objective reinforces the need for quality and overcoming the uneven distribution that exists among institutions that serve different socioeconomic groups. A large study of the quality of perinatal health services in Mexico City demonstrated that neonatal mortality rates (standardized for obstetric risk) were higher in Ministry of Health hospitals, which serve mainly the poor, compared to social security hospitals (Bobadilla and Walker, 1991).

Reform of the Health Care Model

The current health care model of the three countries is inadequate to deal with the increasing complexity of the epidemiological profile. As in many other countries, in these three countries, primary care is weak and underutilized, and most of the public hospitals are overcrowded and used for conditions that could be treated at lower levels of care. Three interrelated changes in the current health care model are proposed to correct these problems.

Increase the Technological Complexity of the Primary Level of Care

The increasing demand for health services that results from a rise in the absolute number of noncommunicable disease cases will not be met adequately with the limited health personnel and restricted technology available at the primary level of care. Common conditions, such as hypertension, ischemic heart disease, cervical dysplasia, cataracts, and varicose veins, can currently be treated with inexpensive treatments. Early detection of many chronic conditions can save resources by reducing the number of cases that advance to more severe stages and require hospitalization. Diagnostic and screening procedures and cost-effective ambulatory therapies should be selected and made available at the primary level of care. This policy should not be implemented, however, if resources are going to be taken from services for maternal and child health, which should still be the priority in poor areas.

Restrict Hospital Care

A second proposed change is to restrict hospital care to the most severe conditions and give priority to conditions amenable to treatment with cost-effective interventions. Low-risk deliveries, sterilizations, and minor surgery are examples of services that can be provided at a lower-level health facility. The next policy proposal defines such a facility.

Create or Strengthen Advanced Primary Health Care Centers

With different names and slight changes in the content, the three countries analyzed here have already recognized the need for a new level of care that would deal with the health problems mentioned previously: low-risk delivery, ambulatory surgery, common diseases, and conditions that require a specialist. This proposal for a more complex intermediate level of care is feasible only for urban areas that have a population base large enough to support such an institution. For this reason, it is important to note that this policy—without the preceding one—could aggravate current inequalities between the urban and rural populations. It is an extremely important strategy to face the fast-growing health problems of urban areas, and defining mechanisms of cooperation between public and private sectors can be very effective because both are already providing care for these conditions. Perhaps the most successful experience that has applied these reforms to the health care model comes from Cali, Colombia. Several reports have shown that with limited investment, these policies led to improved efficiency and effectiveness at the hospital level, greater coverage of delivery care and

other conditions, improvements in the satisfaction of patients, and lower (direct and indirect) costs (Vélez and de Vélez, 1984; Guerrero, 1990).

Improved Efficiency and Quality of Care

The evidence for inefficiency in the use of resources abounds in the health sectors of developing countries (Akin et al., 1987). The most common example is given by the low output of facilities and health personnel at the primary and secondary levels of care. Occupancy rates of less than 40 percent are common in district- and other second-level hospitals, mainly in the public sector. The reasons for this underutilization of resources are related to poor organization of the health centers, lack of resources (drugs, equipment, and other), and poor quality of care. Potential users perceive these services as inadequate to meet their health needs and resort to alternative options, such as private doctors and hospitals or tertiary level of care public hospitals. As a consequence, tertiary-level hospitals are typically overloaded with patients having trivial or nonsevere conditions. Occupancy rates of these hospitals range from 80 to more than 100 percent, depending on the ward. Moreover, many admissions and lengths of stay are not medically justified, adding to the misuse of scarce resources in these hospitals.

The services provided by the ministries of health of Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico all share these characteristics. In Colombia and Mexico, however, the social security and private schemes are more efficient, with higher output per health personnel and health facility. On the other hand, inefficiency in Brazil is high because the National Institute for Medical Care (INAMPS), which originated from the social security system and is now linked with the Ministry of Health, is the largest health scheme in the country and buys most of the hospital services from the private sector. With INAMPS the excess of intervention and the problems of quality are further exacerbated because the control over private practice is very limited (Mello, 1981; McGreevey, 1989; Possas, 1989b).

Suboptimal quality of health care in developing countries is, to a large extent, due to scarcity of resources and administrative inability to deliver the required inputs on time, but more money and resources alone will not improve the standards of care. Unnecessary interventions, which are a reflection of poor quality, occur more often in institutions and facilities where the supply of resources is adequate. Hysterectomies, caesarean sections, tonsillectomies, and appendectomies are only a few of the interventions that are provided excessively in some health institutions of developing and industrialized countries. Brazil and Mexico experience some of the highest levels of caesarean deliveries in the world (Bobadilla, 1988), but paradoxically, in the rural areas of these countries, between 20 and 30 percent of births are not attended by a health professional. Excessive medical

intervention wastes money, produces morbidity and mortality (sometimes offsetting its health benefits at the population level), and entails a high opportunity cost for the health care of the poor.

The problems of the quality of hospital-based services are more difficult to solve and have more severe consequences than those of the health centers or doctors’ offices. It has been documented that cuts in the health budgets of many Latin American countries affected the purchase of drugs and supplies, as well as salary levels, but left the scope, number, and content of existing health programs largely untouched (Cruz et al., 1991). Less money for medical supplies and for equipment, maintenance, supervision, administration, and salaries has produced two effects: an improvement in the efficiency when there was a margin to do so, and a deterioration in the quality of care (Ayala and Schaffer, 1991). Public hospitals have been more severely affected because of the increased demand from the population group that had previously sought attention through private hospitals.

Three policies deserve serious consideration to improve the quality of care and the efficiency of service delivery:

Certification of Hospitals

The diversity of institutions engaged in the provision of services in these three countries suggests that a single nationally recognized commission or office should perform regular evaluations of hospitals. Such a commission ought to be independent of the interested parties and probably separate from the government. Failing to pass the certification a predetermined number of times should lead to closure of a facility. Obviously new laws would be required to make hospitals comply and to settle disputes. This policy has already been suggested for Mexico (Ruelas, 1990).

Certification of Physicians and Other Health Professionals

A system similar to that proposed above would ensure that health professionals update their knowledge and improve their practice over time.

Quality Assurance Systems

Good administration of health facilities is not enough to achieve optimal quality of care. It is necessary to develop information systems on process and outcome that facilitate monitoring the performance of health facilities, particularly hospitals. Peer review systems should be formed with authority to introduce the necessary changes in the organization of an institution and to modify the incentives that guide the behavior of health personnel. The development of techniques and methods for quality assur-

ance has been substantial over the last decade in industrialized countries. There is an urgent need to adapt these techniques and methods, and to train health professionals in this relatively new area of health management (Ruelas, 1990).

The relative rise in noncommunicable diseases will pose additional problems to health institutions that are currently not prepared to deal adequately with complex services. These policies to improve quality are more justified today by the epidemiological transition as the demand for hospital care increases while resources remain the same or decrease.

National Capacity Building for Strategic Health Planning

Debate on the policies for human resource development in these countries has often been polarized around two alternative approaches: (1) comprehensive health care and (2) vertical programs that focus on preventive and/or curative services. The short-term concerns, together with other social and cultural factors, have led governments to neglect investment in analytical-capacity building in fields such as health policy, epidemiology, and health economics. Until this gap is filled, the application of modern methodologies and conceptual frameworks to the analysis of health needs may be seriously jeopardized.

The development of more adequate institutional and management structures to deal with the consequences of the epidemiological transition will require multisectoral activities and multidisciplinary inputs that exceed the limited, medically oriented approach commonly used in the ministries of health and the social security institutes of these countries (Marques, 1989). To face this challenge, countries will need to invest in four critical areas:

Development of Human Resources in Planning and Management

The strengthening of planning and management activities at all levels will require new priorities for health personnel training. The relationships among universities, technical schools, and health institutions will need to be reinforced (Soberón et al., 1988a, b) in a few key areas where collaboration is critical: evaluation of services, cost-effectiveness analysis of alternative interventions, and updating of the curricula and health personnel knowledge.

Better Quality of Health Information Systems

Large amounts of health information are available in middle-income countries, but only a fraction of this is used in decision making (Cordeiro et al., 1990). Even if all the available information were processed and ad-

equately presented for decision making, critical pieces of information would usually still be missing. Finally, the information on births and mortality, collected through vital statistics, is essential for health planning, but the coverage and quality of the data are still deficient in most Latin American countries (Chackiel, 1987).

Development and Strengthening of Essential National Health Research

Essential National Health Research has been proposed (Commission on Health Research for Development, 1990) as one of the most effective means to overcome the heavy burden of disease in developing countries and to reduce the health status inequalities within and among them. This idea refers to the capacity to undertake research on health problems primarily relevant for the developing countries and to advance knowledge on global health issues. It is a system in which the main actors serve both as research-oriented universities, schools of public health, and research centers, and as the providers of health services, and it embodies substantial political commitment, adequate financial support, and the demand for research. Currently, the strength of Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico is in biomedical research, and less so in clinical and public health research (Bobadilla et al., 1988; Cordeiro et al., 1990). The epidemiological transition and the challenges posed to the health system will require a substantial growth in the quantity, relevance, and quality of epidemiological and health systems research.

Capacity Building in Health Technology Assessment

New technologies in clinical medicine are typically additive, inducing more diagnostic and therapeutic procedures—not replacing existing ones (Possas, 1991). This additivity, coupled with rapid technological innovation, has resulted in profound effects on health care costs, with as much as 50 percent of the marginal increments in health care costs being due to new technologies (Panerai and Mohr, 1989). The introduction of new technologies and drugs should be preceded by a thorough assessment of their likely effect on different parts of the health system (cost and effectiveness among other aspects) and on the health of the population (ethical and cultural issues). Such an evaluation requires a critical mass of professionals trained in epidemiology, engineering, health economics, behavioral sciences, and health management. A broad range of modern technologies is already available in these middle-income countries, but limited information and research on the consequences of their incorporation into the health system have been used to approve their purchase and diffusion (Marques, 1989).

CONCLUSION

Since the mid-1980s many developing countries and most of the international agencies that work in the health field have become increasingly aware of the importance of the epidemiological transition. The policy implications of the transition have attracted the attention of scholars and health specialists from a wide variety of disciplines. As a consequence of this renewed interest in the transition, four major positive changes in the conceptual model of health can be identified: (1) health policies are examined through a multidisciplinary approach; (2) health policies deal more with increasing overall health status of populations, and evaluations of the health system are more often linking resources with health improvements; (3) inclusion of health problems of all age groups and not only children in the analysis of the burden of disease, and inclusion of noncommunicable diseases and injury in the spectrum of preventable causes of ill-health; and (4) broadening of health interventions to encompass social policies aimed at reducing environmental risk factors and modifying negative lifestyles.

Examination of the health policies in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico has led us to conclude that there are five main implications of the epidemiological transition for health policy in developing countries. First, the transition offers an empirical framework for strategic planning of the health system, because it allows anticipation of future trends of mortality and its causes, and suggests some of the future scenarios in the burden of disease. Second, because the transition anticipates a greater burden of disease in the adult and elderly populations, the mission of the health system needs to be revised, giving more emphasis to disease prevention and control, and less to demand satisfaction. Third, the current deficiencies of the health system, both organizational and operational, must urgently be corrected because they would be major obstacles in the implementation of other policies intended to improve the health status of the population. Fourth, explicit criteria to set priorities in the health sector need to be defined, so that resources can be distributed among competing socioeconomic groups and health needs. Fifth, the capacity to analyze the health status of populations, evaluate the performance of the health system, and design cost-effective interventions to deal with noncommunicable diseases needs to be strengthened.

Most of the policy issues identified in this paper deal with current deficiencies of the health system and propose ways in which they can be corrected within the legal and financial constraints existing in these countries. A second group of issues suggests ways to deal with the growing burden due to noncommunicable diseases and injury. Most of the suggestions can be implemented without extra financial resources, but call for a substantial reallocation of the available resources.

Only the national level has been analyzed, and this clearly leads to some generalizations that cannot be sustained when provinces or districts are examined. The intracountry variations in health profiles, and the performance and organization of health systems are substantial in the three countries and warrant more detailed analysis of the issues and recommendations made in this paper. Finally, it is worth remembering that immediate political interests have not been considered because they are beyond the scope of this analysis.

The challenge facing all developing countries in the next century will be to define realistic and feasible strategies able to avoid the increasing burden of noncommunicable diseases and injuries before they reach the levels observed in developed countries and, at the same time, to maintain the efforts to reduce the “unfinished agenda.” More than a decade ago, John Evans and colleagues (1981:1126) said that “no satisfactory strategy has been developed to meet the health needs of older children and adults within the financial means of most developing countries” and that “the search for health technology appropriate to the financial and organizational circumstances of developing countries must be seen as a high priority for the research and development community of the entire world.” Research, innovation, creativity, and imagination are readily available for many social problems worldwide. The most rational policy for future health problems in developing countries is to apply our best resources to search for appropriate answers to fill this gap identified more than a decade ago.

REFERENCES

Akin, J., N.Birdsall, and D.de Ferranti 1987 Financing Health Services in Developing Countries: An Agenda for Reform. World Bank Policy Study. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Ayala, R., and C.Schaffer 1991 Salud y Seguridad Social. Crisis, Ajuste y Grupos Vulnerables. Perspectivas en Salud Publica No. 12. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica.

Bell, D. 1993 Some implications of the health transition for policy and research. In L.Chen, A. Kleinman, and N.Ware, eds., Health and Social Change: An International Perspective. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard School of Public Health.

Bobadilla, J.L. 1988 Quality of Perinatal Medical Care in Mexico City. Perspectivas en Salud Pública No. 3. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública.

Bobadilla, J.L., and G.Walker 1991 Early neonatal mortality and cesarean delivery in Mexico City. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 164:22–28.

Bobadilla, J.L., J.Frenk, and J.Sepúlveda 1988 Health research in Mexico: Strengths, weaknesses and gaps. Background paper prepared for the Commission on Health Research for Development, Mexico City.

Bobadilla, J.L., J.Frenk, T.Frejka, R.Lozano, and C.Stern 1993 The epidemiological transition and health priorities. In D.Jamison and H.Mosley, eds., Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. New York: Oxford University Press for the World Bank.

Caldwell, J., S.Findley, P.Caldwell, G.Santow, W.Cosford, J.Braid, and D.Broers-Freeman, eds. 1989 What we know about health transition: The cultural, social and behavioural determinant of health. Proceedings of an International Workshop, Australian National University, Canberra, May.

Chackiel, J. 1987 La investigación sobre causas de muerte en America Latina. Notas de Poblacion 44:9–30. Santiago de Chile: Celade.

Comision Economica para American Latina y el Caribe 1990 Magnitud de la Pobreza en America Latina en Los Anos Ochenta. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL.

Commission on Health Research for Development. 1990 Health Research: Essential Link to Equity in Development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Consejo Consultivo del Programa Nacional de Solidaridad 1990 El Combate a la Pobreza: Lineamientos Programaticos. Mexico: El Nacional, S.A.de C.V.

Cordeiro, H.A. (Coord.), M.B.Marques, C.A.Possas, and P.M.Buss 1990 Prioridades Nacionais, Pesquisa Essencial e Desenvolvimento em Saude. Serie Politica de Saude No. 10, Fundacão Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, 1990. Paper prepared for the workshop held in the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation with the Commision on Health Research for Development, Rio de Janeiro, October.

Cruz, C., R.Lozano, and J.Querol 1991 The Impact of Economic Crisis and Adjustment on Health Care in Mexico. Innocenti Ocassional Papers Number 13. Florence: International Child Development Centre (UNICEF).

Evans, J., K.Lashman Hall, and J.Warford 1981 Shattuck lecture—Health care in the developing world: Problems of scarcity and choice. New England Journal of Medicine 305:1117–1127.

Frenk, J., J.L.Bobadilla, J.Sepúlveda, and M.López-Cervantes 1989 Health transition in middle-income countries: New challenges for health care. Health Policy and Planning 4:29–39.

Frenk, J., J.L.Bobadilla, C.Stern, T.Frejka, and R.Lozano 1991 Elements for a theory of the health transition. Health Transition Review 1:21–38.

Gish, O. 1988 Intervenciones minimas de atencion primaria a la salud para la sobrevivencia en la infancia. Salud Pública de Mexico 30:432–446.

Guerrero, R. 1990 Regionalizacion de la atencion quirurgica: Un ejemplo de investigacion aplicada. In J.Frenk, ed., Salud: de la Investigation a la Action. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Economica.

Jamison, D., and H.Mosley 1991 Disease control priorities in the developing countries: Health policy responses to epidemiological change. American Journal of Public Health 81:15–22.

Laurenti, R. 1990 Transicáo Demográfica e Transicáo Epidemiológica. Anais, 10. Congresso Brasileiro

de Epidemiologia. Epidemiologia e Desigualdade Social: Os Desafios do Final do Século . Campinas: UNICAMP.

Marques, M.B. 1989 A Reforma Sanitária Brasileira e a Política Científica e Tecnológica Necessaria, Serie Política de Saúde No. 8. Rio de Janeiro: FIOCRUZ/NEP.

McGreevey, W.P. 1989 Los altos costos de la atencion de salud en el Brasil. In Economia de la Salud: Perspectivas para America Latina. Organización Panamericana de la Salud, Publicación Cientifica No. 517. Washington, D.C.

Médici, A.C. 1989 Financiamento das políticas de saúde no Brasil. In Economia de la Salud: Perspectivas para America Latina. Organización Panamericana de la Salud, Publicación Cientifica No. 517. Washington, D.C.

Mello, C.G. 1981 O sistema de saude em crise. CEBES-HUCITEC. Sáo Paulo: Colecáo Saude em Debate.

Ministerio de Salud 1990 La Salud en Colombia, Tomo 1. Bogota.

Panerai, R.B., and J.P.Mohr 1989 Health Technology Assessment Methodologies for Developing Countries. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization.

Possas, C. 1989a Epidemiologia e Sociedade: Heterogeneidade Estrutural e Saúde no Brazil. São Paulo: HUCITEC.

1989b Saude e Trabalho: a Crise da Previdencia Social. Prefácio a 2a edicao. São Paulo: HUCITEC.

1991 Fiscal crisis, social changes and health policy strategies in Brazil. Background paper to the discussion of the Takemi Research Proposal, Takemi Program in International Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, October.

Rondinelli, D.A., and G.S.Cheema 1983 Implementing decentralization policies: An introduction. In G.S.Cheema and D.D.Rondinelli, eds., Decentralization and Development Policy Implementation in Developing Countries. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Ruelas, E. 1990 Transiciones indispensables: De la cantidad a la calidad y de la evaluacion a la garantia. Salud Pública de Mexico 2:108–110.

Rutstein, S.O. 1992 Levels, trends and differentials in infant and child mortality in the less developed countries. Pp. 17–42 in K.Hill, ed., Child Survival Priorities for the 1990s. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Institute for International Programs.

Soberón, G., J.Kumate, and J.Laguna 1988a La Salud en México: Testimonies 1988. I. Fundamentos del Cambio Estructural. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Soberón, G., J.Frenk, and A.Langer 1988b Requerimientos del paradigma de la atención primaria a la salud en los albores del siglo XXI. Salud Pública de México 30:791–803.

United Nations Children’s Fund 1992 The State of the World’s Children 1992. New York: Oxford University Press.

Vélez, A., and G.de Vélez 1984 Investigation de modelos de atención en cirugia: Programa sistema de cirugia simplificada. Educacion Médica y Salud 8.

Vianna, S.M., S.F.Piola, A.J.E.Guerra, and S.F.Camargo 1990 O Financiamento da Descentralizacáo dos Services de Saúde: Criterios para transferencias de Recursos Federais para Estados e Municipios. Série Economia e Financiamento No. 1. Brasilia: OPAS, Representacáo.

World Bank 1991 World Development Report 1991: The Challenge of Development. Washington, D.C.

1992 Global Health Statistics. Unpublished tables. World Health Organization, Washington, D.C.

World Health Organization 1990 1989 World Health Statistics Annual. Geneva: World Health Organization.

APPENDIX

Economic, Social, and Health Status Characteristics of Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico

BRAZIL

Economic

Per capita GDP (1989): U.S. $2,540.a

Average annual inflation (1980–1989):>200%.a

Very high income concentration (1983): highest 10% with 46% of income, and lowest 20% with 2.4% of income.a

Socialb

Population in poverty (1987):45%.c

Access to safe water (1983–1986):75%.d

Access to sanitation facilities (1983–1986):78%.d

Illiteracy rate in adult population (1985):22%.a

Heath Status

Life expectancy at birth (1984):66 years.a

Mortality under 5 (1989):8.5%.a

Percentage of deaths due to infectious diseases (1985):12%.e

Malaria, tuberculosis, and AIDS are rising very fast.

Cholera is spreading fast from the north and northeast.

Life expectancy is 16 years lower in the northeast than in the southf

COLOMBIA

Economic

Per capita GDP (1989): U.S. $1,200.a

Average annual inflation (1980–1989):24%.a

Very high income concentration (1988): highest 10% with 37% income and lowest 20% with 4% income.a

Socialb

Population in poverty (1986):42%.c

Access to safe water (1985):88%.d

Access to sanitation facilities (1985):65%.d

Illiteracy rate in adult population (1985):12%.a

Health Status

Life expectancy at birth (1989):69 years.a

Mortality under 5 (1989):5.0%.d

Percentage of deaths due to infectious diseases (1986):10%.e

Violence and other cause of injury are probably the major cause of premature mortality.

Malaria and cholera are resurging.

MEXICO

Economic

MEXICO—

Socialb

Population in poverty (1984):37%.c

Access to safe water (1983–1985):69%.d

Access to sanitation facilities (1983–1985):45%.d

Illiteracy rate in adult population (1985):10%.a

Health Status

Life expectancy at birth (1989):69 years.a

Mortality under 5 (1989):5.1%.d

Percentage of deaths due to infectious diseases (1986):20%.e

Malnutrition in rural areas is still a high public health priority; inequalities of health status between population groups are very wide.

Oaxaca has a life expectancy 12 years less than Nuevo Léon.

NOTE: GDP=gross domestic product.

|

a |

World Bank (1991). |

|

b |

Population in poverty is defined as those who earn an income less than two times the required amount to purchase the basic food basket. |

|

c |

Comision Economica para America Latina y el Caribe (1990). |

|

d |

World Bank (1992). |

|

e |

See Table 2 footnotes for sources. |

|

f |

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estadistica (1984). |

|

g |

Consejo Consultivo del Programma Nacional de Solidaridad (1990). |