3

Fonio (Acha)

Fonio (Digitaria exilis and Digitaria iburua) is probably the oldest African cereal. For thousands of years West Africans have cultivated it across the dry savannas. Indeed, it was once their major food. Even though few other people have ever heard of it, this crop still remains important in areas scattered from Cape Verde to Lake Chad. In certain regions of Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea, and Nigeria, for instance, it is either the staple or a major part of the diet. Each year West African farmers devote approximately 300,000 hectares to cultivating fonio, and the crop supplies food to 3-4 million people.

Despite its ancient heritage and widespread importance, knowledge of fonio's evolution, origin, distribution, and genetic diversity remains scant even within West Africa itself. The crop has received but a fraction of the attention accorded to sorghum, pearl millet, and maize, and a mere trifle considering its importance in the rural economy and its potential for increasing the food supply. (In fact, despite its value to millions only 19 brief scientific articles have been published on fonio over the past 20 years.)

Part of the reason for this neglect is that the plant has been misunderstood by scientists and other decision makers. In English, it has usually been referred to as "hungry rice," a misleading term originated by Europeans who knew little of the crop or the lives of those who used it.1 Unbeknownst to these outsiders, the locals were harvesting fonio not because they were hungry, but because they liked the taste. Indeed, they considered the grain exotic, and in some places they reserved it particularly for chiefs, royalty, and special occasions. It also formed part of the traditional bride price. Moreover, it is still held in such esteem that some communities continue to use it in ancestor worship.2

Not only does this crop deserve much greater recognition, it could have a big future. It is one of the world's best-tasting cereals. In recent

times, some people have made side-by-side comparisons of dishes made with fonio and common rice and have greatly preferred the fonio.

Fonio is also one of the most nutritious of all grains. Its seed is rich in methionine and cystine, amino acids vital to human health and deficient in today's major cereals: wheat, rice, maize, sorghum, barley, and rye. This combination of nutrition and taste could be of outstanding future importance. Most valuable of all, however, is fonio's potential for reducing human misery during "hungry times."

Certain fonio varieties mature so quickly that they are ready to harvest long before all other grains. For a few critical months of most years these become a "grain of life." They are perhaps the world's fastest maturing cereal, producing grain just 6 or 8 weeks after they are planted. Without these special fonio types, the annual hungry season would be much more severe for West Africa. They provide food early in the growing season, when the main crops are still too immature to harvest and the previous year's production has been eaten.

Other fonio varieties mature more slowly—typically in 165-180 days. By planting a range of quick and slow types farmers can have grain available almost continually. They can also increase their chances of getting enough food to live on under even the most changeable and unreliable growing conditions.

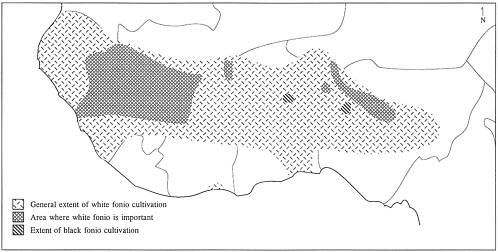

Of the two species, white fonio (Digitaria exilis) is the most widely used. It can be found in farmers' fields from Senegal to Chad. It is grown particularly on the upland plateau of central Nigeria (where it is generally known as "acha") as well as in neighboring regions.

The other species, black fonio (Digitaria iburua), is restricted to the Jos-Bauchi Plateau of Nigeria as well as to northern regions of Togo and Benin.3 Its restricted distribution should not be taken as a measure of relative inferiority: black fonio may eventually have as much or even greater potential than its now better-known relative.

PROSPECTS

Unlike finger millet, African rice, sorghum, and other native grains, fonio is not in serious decline. Indeed, it is well positioned for improved production. First, it is still widely cultivated and is well known. Second, it is highly esteemed. (In Nigeria's Plateau State, for example, the present 20,000-ton production is only a quarter of the projected state demand.4) Third, it tolerates remarkably poor soil and will grow

where little else succeeds. These are good underpinnings for fonio's future advancement.

Africa

Humid Areas

Low prospects. Fonio is mainly a plant of the savannas and is probably ill adapted to lowland humid zones. It seems likely to succumb to various fungal and bacterial diseases. However, white fonio does grow around the Gola Forest in southeastern Sierra Leone, and black fonio is reportedly cultivated in Zaire and some other equatorial locations. These special varieties (occasionally misnamed as Digitaria nigeria) are possibly adapted to hot and humid conditions.

Dry Areas

High prospects. People in many dry areas of West Africa like fonio. They know that it originated locally, and they have long-established traditions for cultivating, storing, processing, and preserving it. During thousands of years of selection and use, they have located types well adapted to their needs and conditions. Although the plant is not as drought resistant as pearl millet, the fast-maturing types are highly suited to areas where rains are brief and unreliable.

Upland Areas

Excellent prospects. Fonio is the staple of many people in the Plateau State of Nigeria and the Fouta Djallon plateau of Guinea, both areas with altitudes of about 1,000 m.

Other Regions

This plant should not be moved out of its native zones. In more equable parts of the world it might become a serious weed.5

USES

Fonio grain is used in a variety of ways. For instance, it is made into porridge and couscous, ground and mixed with other flours to make breads, popped,6 and brewed for beer. It has been described as

a good substitute for semolina—the wheat product used to make spaghetti and other pastas.

In the Hausa region of Nigeria and Benin, people prepare a couscous (wusu-wusu) out of both types of fonio. In northern Togo, the Lambas brew a famous beer (tchapalo) from white fonio. In southern Togo, the Akposso and Akebou peoples prepare fonio with beans in a dish that is reserved for special occasions.

Fonio grain is digested efficiently by cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys, and other ruminant livestock. It is a valuable feed for monogastric animals, notably pigs and poultry, because of its high methionine content.7 The straw and chaff are also fed to animals. Both make excellent fodder and are often sold in markets for this purpose. Indeed, the crop is sometimes grown solely for hay.

The straw is commonly chopped and mixed with clay for building houses or walls. It is also burned to provide heat for cooking or ash for potash.

NUTRITION

In gross nutritional composition, fonio differs little from wheat. In one white fonio sample, the husked grain contained 8 percent protein and I percent fat.8 In a sample of black fonio, a protein content of 11.8 percent was recorded.9

The difference lies in the amino acids it contains. In the white fonio analysis, for example, the protein contained 7.3 percent methionine plus cystine. The amino acid profile compared to that of whole-egg protein showed that except for the low score of 46 percent for lysine, the other scores were high: 72 for isoleucine; 90-100 for valine, tryptophan, threonine, and phenylalanine; 127 for leucine; 175 for total sulfur; and 189 percent for methionine.10

This last figure means that fonio protein contains almost twice as much methionine as egg protein contains. Thus, fonio has important potential not only as survival food, but as a complement for standard diets.

AGRONOMY

Fonio is usually grown on poor, sandy, or ironstone soils that are considered too infertile for pearl millet, sorghum, or other cereals. In

NUTRITIONAL PROMISE

|

Main Components |

|

Essential Amino Acids |

|

|

Moisture |

10 |

Cystine |

2.5 |

|

Food energy (Kc) |

367 |

Isoleucine |

4.0 |

|

Protein (g) |

9.0 |

Leucine |

10.5 |

|

Carbohydrate (g) |

75 |

Lysine |

2.5 |

|

Fat (g) |

1.8 |

Methionine |

4.5 |

|

Fiber (g) |

3.3 |

Phenylalanine |

5.7 |

|

Ash (g) |

3.4 |

Threonine |

3.7 |

|

Thiamin (mg) |

0.47 |

Tryptophan |

1.6 |

|

Riboflavin (mg) |

0.10 |

Tyrosine |

3.5 |

|

Niacin (mg) |

1.9 |

Valine |

5.5 |

|

Calcium (mg) |

44 |

|

|

|

Iron (mg) |

8.5 |

|

|

|

Phosphorus (mg) |

177 |

|

|

COMPARATIVE QUALITY

Guinea's Fouta Djallon region, where fonio is common, the soils are acidic clays with high aluminum content—a combination toxic to most food crops. It is generally grown just like upland rice, and the two are frequently produced by the same farmers. Normally, the seed is broadcast and covered by a light hoeing. It germinates in 3-4 days and grows very rapidly. This quick establishment and the heavy seeding rate (usually 10-20 kg of seed per hectare) ensures that the fields seldom need weeding. In a few cases the crop is transplanted from seedbeds to give it an even better chance at surviving the harsh conditions.

In Sierra Leone, and probably elsewhere, fonio is often grown following, or even instead of, wetland rice. This is done particularly when the season proves too dry for good paddy production and the farmers decide to give up on the rice. Fonio thus serves as an insurance against total crop failure.

In certain areas, fonio may sometimes be planted together with sorghum or pearl millet. Indeed, it is frequently the staple, while the other two are considered reserves. Commonly, farmers in Guinea sow multiple varieties of fonio and then later fill in any gaps with fast maturing varieties of guinea millet (Brachiaria deflexar).11

HARVESTING AND HANDLING

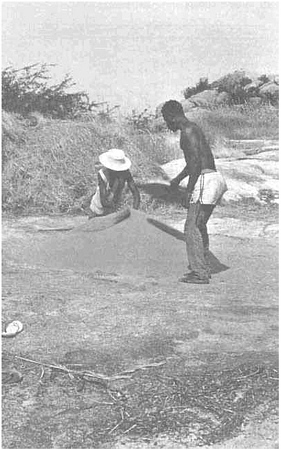

Fonio grain is handled in traditional ways. The plants are usually cut with a knife or sickle, tied into sheaves, dried, and stored under cover. Good yields are normally 600-800 kg per hectare, but more than 1,000 kg per hectare has been recorded. In marginal areas, yields may drop to below 500 kg and on extremely poor soils may be merely 150-200 kg per hectare.12

Traditionally, the grain is threshed by beating or trampling, and it is dehulled in a mortar. This is difficult and time-consuming.

The seed stores well.

LIMITATIONS

Because of the lack of attention, fonio is still agronomically primitive. It suffers from small seeds, low yields, and some seed shattering.

The plant responds to fertilizers, but most types are so spindly that fertilization makes them top-heavy and they may blow over (lodge).

|

Fonio: It's Not Just a Famine Food Late in 1990, I interviewed a farmer with a largish plot of fonio. It was just a few kilometers from Bo town, in central Sierra Leone. What especially intrigued me was that this was not, as I at first supposed, a poverty-stricken woman's attempt to grow a little food for household subsistence. It was instead a commercial venture, aimed at the Bo market. There, fonio sells (cup for cup) at a better price than rice. By selling her crop she would be able to buy a larger amount of rice. To me, this was a striking confirmation of the commercial potential of this almost entirely neglected crop. To the people who know it, fonio is treasured more highly than rice! Paul Richards |

Birds may badly damage the crop in some areas; bird-scaring is usually necessary in those locations. The plants are also susceptible to smut and other fungal diseases.

It has been reported that fonio causes soil deterioration, but this appears to be a misperception. It is often sown on worn-out soils, sometimes even after cassava (the ultimate crop for degraded lands elsewhere). It is this association with poor soils that has given rise to the rumor, but the soils were in fact impoverished long before the fonio was put in.

Some groups dislike black fonio because, compared with the white form, it is more difficult to dehusk with the traditional pestle.

The seed loses its viability after two years.

Because of its small seed size, the harvest is very difficult to winnow. Sand tends to remain with the seed and produces gritty foods. It is therefore necessary to thresh fonio on a hard surface rather than on bare ground. Also, just before cooking, the grains are usually washed to rid them of any remaining sand.

NEXT STEPS

Clearly, fonio is important, has many agronomic and nutritional virtues, and could have an impressive future. This crop deserves much greater attention. Modern knowledge of cereal-crop improvement and dedicated investigations are likely (at modest cost) to make large advances and improvements. Yields can almost certainly be raised

dramatically, farming methods made less laborious, and markets developed—all without affecting the plant's resilience and reliability. These results, and more, are likely to come about quickly once fonio becomes as important to the world's scientists as it is to West Africa's farmers.

Promotion

General activities to raise awareness of this crop's value and potential include a monograph, a newsletter, a ''friends of fonio" society, a fonio cookbook, a series of fonio cook-offs, and fonio conferences. These could be complemented by publicity, seed distributions, and experiments to test fonio's farm qualities and cultivation limits.

It should not be too difficult to generate excitement for this "lost gourmet food of the great ancestors." It might prove a good basis for recreating traditional cuisines. Even export as a highly nutritious specialty grain is a possibility.

Scientific Underpinnings

Despite its importance, fonio is a crop less than halfway to its potential. There have been few, if any, attempts to optimize, on a scientific basis, the process of growing it. Its taxonomy, cultivation, nutritional value, and time to harvest are only partially documented. Varieties have neither been compared, nor their seed even collected, on a systematic basis. Little or no research has been done on postharvest deterioration, storage, or preservation methods.

Germplasm Collection

An early priority should be to collect germplasm.13 Varieties are particularly numerous in the Fouta Djallon Plateau in Guinea and around the upper basins of the Senegal and Niger Rivers.14 Among these will certainly be found some outstanding types. This alone seems likely to lead to better cultivars that will bring marked advances in fonio production. The collection should also be screened to determine if yield is limited by viruses.15 If so, the creation of virus-free seed might also boost yields dramatically.

Seed Size

The smallness of the grain offers a special challenge to cereal scientists: can the seeds be enlarged—perhaps through selection, hybridization, or other genetic manipulation?

Yield

The cause of the low yields needs investigation. Is it because of the sites, diseases and pests, poor plant architecture, inefficient root structure, lodging, poor tillering, bolting, or daylength restrictions? What are optimum conditions for maximum yields? Can fonio's productivity approach that of the better-known cereals'?

Grain Quality

Cereal chemists should analyze the grains. What kinds of proteins are present? What are the amino-acid profiles of the different proteins? Nutritionists should evaluate the biological effectiveness of both the grains and the products made from them. There are probably happy surprises waiting to be discovered. In particular, protein fractionation is likely to turn up fractions with methionine and cystine levels even greater than fonio's already amazingly high average.

The exceptional content of sulfur amino acids (methionine plus cystine) should make fonio an excellent complement to legumes. Feeding studies to verify this are in order. The combination could be nutritionally outstanding.

Cytogenetics

As a challenge to geneticists, fonio has a special fascination. It has no obvious wild ancestor. That it appears to be a hexaploid (2n=6x=54) may help account for this. Does it, in fact, contain three diploid genomes of different origin? What are its likely ancestors, and might they be used to increase its seed size and yield?

Plant Architecture

Lodging is a serious drawback, especially when the soil is fertile. This may be overcome by dwarfing the plant or endowing stronger stems by plant breeding. How "free-tillering" are the various types?

Other Uses

Certain other Digitaria species are cultivated exclusively as fodder, whereas some are notable for their soil-binding properties and ability to produce an excellent turf. Is fonio also useful for such purposes? Could it, too, become a valuable all-purpose plant for many regions? Could improved fonio be "naturalized" in the northern Sahel to increase the availability of wild grain to nomadic groups?

Sociocultural Factors

How is the crop currently cultivated, distributed, and processed? What roles are played by social and cultural

factors such as the division of labor, traditional beliefs, and people's expectations? (Fonio, after all, is seldom if ever grown under optimum conditions.) Its promotion will succeed best in West Africa if its development is placed within such local constraints.

Processing

The processing and cooking of this crop is extremely arduous. Unless this can be relieved, fonio will probably never reach its potential.

SPECIES INFORMATION

Botanical Names

Digitaria exilis Stapf and Digitaria iburua Stapf16

Synonyms

Paspalum exile Kippist; Panicum exile (Kippist) A. Chev.; Syntherisma exilis (Kippist) Newbold; Syntherisma iburua (Stapf) Newbold (for Digitaria iburua)

Common Names

English: hungry rice, hungry millet, hungry koos, fonio, fundi millet

French: fonio, petit mil (a name also used for other crops)

Fulani: serémé, foinye, fonyo, fundenyo

Bambara: fini

Nigeria: acha (Digitaria exilis, Hausa); iburu (Digitaria iburua, Hausa); aburo

Senegal: eboniaye, efoleb, findi, fundi

The Gambia: findo (Mandinka)

Togo: (Digitaria iburua); afio-warun (Lamba); ipoga (Somba, Sampkarba); fonio ga (black fonio); ova (Akposso)

Mali: fani, feni, foundé

Burkina Faso: foni

Guinea: pende, kpendo, founié, pounié

Benin: podgi

Ivory Coast: pom, pohin

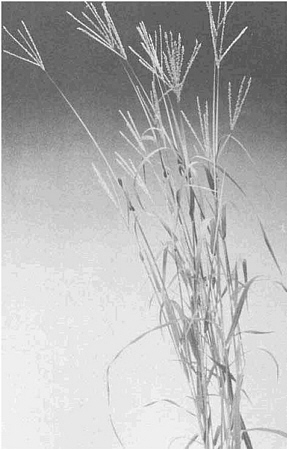

Description

As noted, there are actually two species of fonio. Both are erect, free-tillering annuals. White fonio (Digitaria exilis) is usually 30-75 cm tall. Its finger-shaped panicle has 2-5 slender racemes up to 15 cm

|

Fonio as Fast Food As noted elsewhere (especially in Appendix C), a lack of processed products is holding back Africa's native grains. One grass-roots organization is doing something about this: it is turning fonio into a convenience food. In southern Mali, fonio is mainly grown by women on their individual plots. Perhaps not unexpectedly, then, it is a women's group that has chosen to foster the grain's greater use. The group aims to raise fonio consumption by producing a precooked flour. The project, backed by the Malian Association for the Promotion of the Young (AMPJ), is staffed and run entirely by women. Their goal is a fast-cooking fonio that will challenge parboiled rice and pre-packaged pasta (both of which are usually imported) in the Bamako markets. The new "instant" fonio comes in 1-kg plastic bags and is ready for use. It requires no pounding or cleaning. It can be used to prepare all of the traditional fonio dishes. It is simple to store and handle. It is clean and free of hulls and dirt. And it requires less than 15 minutes to cook. For the user, then, it offers an enormous saving in both effort and time. The project is currently a small one, designed to handle 6 tons of raw fonio per year. It uses local materials, traditional techniques, and household equipment: mortars, tubs, calabashes, steaming pots, sieves, matting, kitchen scales, and small utensils. The women sieve, crush, wash, and steam-cook the fonio; then they dry and seal the product in the airtight bags. The most delicate operation is a series of three washes to separate sand from the fine fonio grains. The women have organized themselves into small working groups, formed for (1) the supply of raw materials, (2) production and packaging, and (3) marketing. Fonio is considered a prestige food in local culinary customs. Yet, on the Bamako market this precooked product currently sells at a very competitive price: between 500 and 550 CFA Francs per kg. (By comparison, couscous sells at 650-750 CFA Francs.) This small and homespun operation exemplifies what could and should be done with native grains throughout Africa. It is good for everyone: diversifying the diet of city folks, reducing food imports, and, above all, benefitting the local farmers by giving them a value-added product. |

long. Black fonio (Digitaria iburua) is taller and may reach 1.4 m. It has 2-11 subdigitate racemes up to 13 cm long.

Although both species belong to the same genus, crossbreeding them seems unlikely to yield fertile hybrids, as they come from different parts of the same genus.17

The grains of both species range from "extraordinarily" white to fawn yellow or purplish. Black fonio's spikelets are reddish or dark brown. Both species are more-or-less nonshattering.

Distribution

Fonio is grown as a cereal throughout the savanna zone from Senegal to Cameroon. It is one of the chief foods in Guinea-Bissau, and it is also intensively cultivated and is the staple of many people in northern Nigeria. Fonio is not grown for food outside West Africa.

Cultivated Varieties

There are no formal cultivars as such, but there are a number of recognized landraces, mainly based on the speed of maturity.

Environmental Requirements

Daylength

Flowering is apparently insensitive to daylength.

Rainfall

Fonio is extremely tolerant of high rainfall, but not—on the whole—of excessive dryness. The limits of cultivation (depending on seasonal distribution of rainfall) are from about 250 mm up to at least 1,500 mm. The plant is mostly grown where rainfall exceeds 400 mm. By and large, the precocious varieties are cultivated in dry conditions and late varieties in wet conditions.

Altitude

Although fonio is grown at sea level in, for instance, Sierra Leone, the Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau, its cultivation frequently is above 600 m elevation.

Low Temperature

Unreported.

High Temperature

Unreported.

Soil Type

It is grown mainly on sandy, infertile soils. It can, however, grow on many poor, shallow, and even rocky soils. Most