2

Nature and Scope of Violence Against Women

The problem of violence against women has gained increasing attention in recent years, but the scope and magnitude of the problem are the subjects of on-going debates (e.g., Gilbert, 1995). For example, studies of how many women experience rape in their lifetimes have reported as few as 2 percent (Riger and Gordon, 1981; Harris, 1993) and as many as 50 percent (Russell, 1984); most estimates fall between 13 and 25 percent (Koss and Oros, 1982; Hall and Flannery, 1984; Kilpatrick et al., 1987, 1992; Koss et al., 1987, 1991; Moore et al., 1989). There are similar debates about the number of battered women. Similar wide discrepancies are reported for women who experience violence by an intimate partner: annual rates range from 9.3 per 1,000 women (Bachman and Saltzman, 1995) to 220 per 1,000 women (Meredith et al., 1986). The most often cited figures come from the National Family Violence Surveys (Straus and Gelles, 1990), which found a rate of 116 per 1,000 women for a violent act by an intimate partner during the preceding year and 34 per 1,000 for "severe violence" by an intimate partner. The debates about scope and magnitude sometimes overshadow and di-

vert attention from the discussion of the actual problem of violence against women, its consequences, and what can be done to prevent it.

This chapter highlights what is known about the extent of violence against women. It first reviews the data on the most extreme violence, that which ends in death. For nonfatal violence, the chapter considers information gathered from representative sample surveys and official data sources and discusses reasons for discrepancies in study findings. It also discusses gaps in the data, uses for data, and offers recommendations for improving the information about both the extent and nature of violence against women.

Fatal Violence

Data on homicides in the United States are collected by two sources—the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The FBI's Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) system collects basic information on serious crimes from participating police agencies and records supplemental information about the circumstances of homicides. The NCHS collects and tabulates data on causes of death, including homicide, from death certificates. The NCHS data provides detail on causes of death by homicide, by age, sex, and race, but it does not provide information on the offender-victim relationship.

Although U.S. homicide rates are substantially higher for men than for women—16.2 and 4.1 per 100,000, respectively (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1993; Kochanek and Hudson, 1995)—homicide ranks similarly as a cause of death for both men and women; see Table 2.1. Homicide is the second leading cause of death for those aged 15-24 and the fourth leading cause for those aged 10-14 and 25-34. However, the pattern of offender-victim relationship for homicides has changed since the 1960s for men, but not for women. Today, men are more likely to be killed by a stranger or an unidentified assailant, while women are still substantially more likely to be killed

TABLE 2-1. Rank of homicide as a cause of death, by sex and age,1990

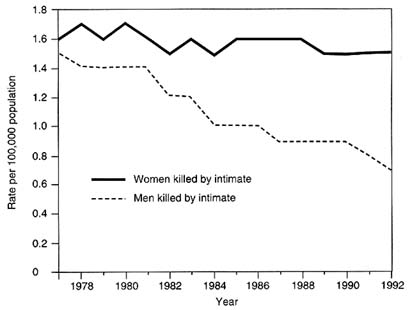

by a male intimate or an acquaintance (Mercy and Saltzman, 1989; Kellermann and Mercy, 1992; Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1993). In 1993, of the 4,869 female homicide victims (aged 10 and over), 1,531 (31 percent) were killed by husbands, ex-husbands, or boyfriends; of the 17,457 male homicide victims (aged 10 and over), only 591 (3 percent) were killed by wives, ex-wives, or girlfriends (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1993). The rate of homicide by an intimate has remained remarkably stable for women, but not for men; see Figure 2.1. The rate for women was between 1.5 and 1.7 per 100,000 from 1977 to 1992. For men, however, the rate dropped from 1.5 per 100,000 in 1977 to 0.7 per 100,000 in 1992 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1994). It has been suggested that the availability of services for battered women, which began in the late 1970s, may have played a role in the decrease in males killed by intimates by offering women alternative means of escaping violent situations (see, e.g., Browne and Williams, 1989).

FIGURE 2-1 Rates of homicide by relationship to offender.

NOTE: Intimate includes spouse, ex-spouse, and boyfriend or girlfriend.

SOURCE: Bureau of Justice Statistics (1994:9)

Women, like men, are most likely to be murdered with a firearm (see, e.g., Kellermann and Mercy, 1992): 70 percent of all homicides in the United States in 1993 were committed with a firearm (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1993). The risk of homicide in the home by a family member or intimate for both women and men is 7.8 times higher if a gun is kept in the home (Kellermann et al., 1993). Thus, laws that allow judges to require persons against whom temporary restraining orders (known also as protection-from-abuse orders) have been issued to relinquish firearms in their possession may help reduce the lethality of violence against women; the question has not yet been directly studied.

U.S. homicide rates are significantly higher for women of color than for white women: 10.7 per 100,000 for all women of color; 13.1 per 100,000 for African American women; 2.8 per 100,000 for white women (Kochanek and Hudson, 1995).

The same pattern holds for homicides by intimates. In 1992, the rate of intimate homicide of African American women aged 18 to 34 was 6 per 100,000; for whites in that age group the rate was 1.4 per 100,000 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1994).1

The overall homicide rate in the United States is 9.3 per 100,000 persons (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1993), far higher than that of most other developed nations. For example, in Canada, a country that classifies most criminal offenses under rules similar to those in the United States, the 1993 homicide rate was slightly over 2 per 100,000. Interestingly, the homicide rate for Canadian women killed by their spouses is comparable to that in the United States, averaging 1.3 per 100,000 women each year; however, Canadian men are killed by their spouses at a rate of 0.4 per 100,000, about half the rate in the United States (Statistics Canada, 1994).

Nonfatal Violence

Official and Survey Data

Information on the scope of nonfatal violence against women comes from both official records and survey data. Thirty-five states collect some statistical information on domestic violence, and 30 states collect statistical data on sexual assaults (Justice Research and Statistics Association, 1996). However, the source and nature of the data vary greatly from state to state. Some states collect data from health or social service sources, such as hospital emergency rooms, other health care providers, or victim service provider records, but most of the data collected come from the criminal justice system, particularly from law enforcement agencies.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics of the Department of Justice and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the Department of Health and Human Services have each funded demonstration projects to attempt to integrate data from the various sources to create a comprehensive data set

on violence against women. While such data sets could be of great value to researchers and policy makers, concerns about confidentiality and the use of the data must be taken into account. For example, recording of domestic violence in women's medical records has resulted in some women being denied health insurance because domestic violence was classified as a preexisting condition.

The most consistently collected and commonly used official data set is the UCR. Because the FBI has been collecting and annually tabulating UCR data since 1930, they provide long-term, national trends. But the UCR includes only incidents that are considered crimes and that have been reported to the police. Based on comparisons with national survey data, it is estimated that only 40 to 50 percent of crimes become known to police (Reiss and Roth, 1993), and that percentages may be much lower for violent crimes against women. For example, a major survey of family violence found that only 6.7 percent of women assaulted by an intimate had reported the incident to police (Straus and Gelles, 1990). UCR rates further depend on the recording of reported incidents by the police as crimes. What is recorded may vary because of differences in state statutes (for example, marital rape would not be counted in those states in which it is not a crime), as well as by differences in policies among jurisdictions and the discretionary judgments of individual police officers. Furthermore, the UCR contains little information about nonfatal crimes other than race, age, and sex of arrested offenders; offender-victim relationship is not recorded.

In order to overcome the limitations inherent in official data, researchers have turned to surveys to gain a fuller picture of violence against women. Standard measures in survey research include incidence and prevalence. Incidence is the number of new cases within a specified time period (often, a year). Prevalence is the rate of established cases within a specified time period. Most of the surveys on violence against women measure either annual prevalence or lifetime prevalence (or both). Annual prevalence rates are important for

looking at trends in the rate of violence over time; lifetime prevalence rates give an indication of the number of women who will be affected in the course of their lifetimes.

The primary sources for national data on violence against women are the two waves of the National Family Violence Survey (reported in Straus et al., 1980; Straus and Gelles, 1990), the on-going National Crime Victimization Survey,2 and, for sexual assault, the National Women's Study (Kilpatrick et al., 1992). A number of other studies have addressed a distinct subpopulation or specific topic. Table 2.2 lists representative studies, their characteristics, and their findings.

Many of the studies on sexual assault cited in Table 2.2 were funded by the National Center for the Prevention and Control of Rape, which was located in the National Institute of Mental Health from 1976 until its termination in 1987. Currently, both foundation and federal government funding sources emphasize ameliorating the aftereffects rather than assessing the nature and scope of violence against women. Overall, there have been few survey studies on violence against women, and methodological constraints have precluded direct comparison across investigations, yet few resources in either the public or private sector are currently available for such work.

Research Findings

The more than 20 years of survey research on violence against women show a number of consistent patterns. The most common assailant is a man known to the woman, often her male intimate. This holds true for both sexual (e.g., Russell, 1982; Bachman and Saltzman, 1995) and physical (e.g., Kellermann and Mercy, 1992) assault. It also holds true for African Americans (e.g., Wyatt, 1992), Mexican Americans (e.g., Sorenson and Telles, 1991), and whites (e.g., Russell, 1982) and for both urban (e.g., Russell, 1982; Wyatt, 1992) and rural (e.g., George et al., 1992) populations.

TABLE 2-2 Representative sample studies of violence against women in the United States

|

Auther(s) and Year |

Sample |

Ethnic composition |

Locale |

Findings |

|

Sexual Assault |

||||

|

Russell, 1982 |

930 adult women |

Representative of area population |

San Francisco |

Lifetime rape reported by 24% |

|

Hall and Flannery, 1984 |

508 adolescents (age 14-17) |

—a |

Milwaukee |

Lifetime rape or sexual assault reported by 12% |

|

Essock-Vitale and McGuire, 1985 |

300 women, 35-45 years old |

100% white |

Los Angeles |

Lifetime rape or molestation reported by 22% |

|

Kilpatrick et al., 1985 |

2,004 adult women |

66% white 44% nonwhiteb |

Charleston County, SC |

Lifetime forcible rape reported by 8.8% |

|

Sorenson et al., 1987 |

1,645 women, 18-39 years old 1,480 adult men |

6% Hispanic 42% non-Hispanic white, 13% other |

Los Angeles |

Lifetime sexual assault reported by 10.3% of Hispanic women, 26.3 % of non-Hispanic white women and 10% of all men |

|

Wyatt, 1992 |

248 women, 18-36 years old |

50% African American 50% white |

Los Angeles |

Rape since age of 18 reported by 25% of African American and 20% of white women |

|

Kilpatrick et al., 1992 |

4,008 adult women |

—a |

United States |

Lifetime rape reported by 13% |

|

George et al., 1992 |

1,157 adult women |

60.3% white 39.7% African American |

Five counties in North Carolina |

Lifetime sexual assault reported by 5.9% |

|

Physical Assault by Intimate Partner |

||||

|

Straus et al., 1980: National Family Violence Survey, 1975 |

2,146 adults |

Representative of U.S. population |

United States |

Past year physical violence reported by 12.1% of women; past year severe violence reported by 3.8% of women |

|

Schulman, 1979 |

1,793 adult women |

Representative of state |

Kentucky |

Past year physical violence reported by 10%; ever experienced physical violence reported by 21% |

|

Straus and Gelles, 1990: National Family Violence Survey, 1985 |

6,002 households |

Representative of U.S. population |

United States |

Past year physical violence reported by 11.6% of women; past year severe violence reported by 3.4% of women |

|

a Information not reported in study. b Most nonwhite sample members were African American, with not more than 1% accounting for any other racial classification (e.g., Hispanic, American Indian, or Asian). |

||||

The highest rates of violence are experienced by young women. The average annual rate of victimization is 74.6 per 1,000 for women aged 12-18 and 63.7 per 1,000 for women aged 19-29; in comparison, the average annual rate for all women is 36.1 (Bachman and Saltzman, 1995). Although the actual rates may vary, the age trend is similar for homicides (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1993), sexual assaults (Kilpatrick et al., 1992), and intimate partner violence (e.g., Straus and Gelles, 1990).

Women self-report violent actions toward their male partners at rates similar to or higher than men self-report violent actions toward their female partners (e.g., Straus and Gelles, 1986). However, men consistently have been found to report their own use of violence as less frequent and less severe than their female partners report it to be (Szinovacz, 1983; Jouriles and O'Leary, 1985; Edleson and Brygger, 1986; Fagan and Browne, 1994). Furthermore, rates do not provide information on the outcome of the act or whether the violent act was one of self-defense or attack, so the meaning of this finding is unclear. Both survey findings and health and crime data do indicate, however, that women are more frequently and more seriously injured by intimates than are men (Langan and Innes, 1986; Stets and Straus, 1990; Browne, 1993; Fagan and Browne, 1994).

Differences in study findings are primarily ones of magnitude rather than substance. For example, although risk characteristics (e.g., being young) and assault characteristics (e.g., by a known man) are fairly consistent across studies, estimates of the lifetime prevalence of sexual assault range from 2 percent (Riger and Gordon, 1981) to 50 percent (Russell, 1984) with most estimates hovering around 20 percent (e.g., Brickman and Briere, 1984; Essock-Vitale and McGuire, 1985). There have been so few representative sample investigations of physical violence against women that cross-study comparisons are necessarily limited. The 1992-1993 National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) found 34.7 of every 1,000 women had been victims of assault in a year: 8 per 1,000 for

aggravated assault and 26.7 per 1,000 for simple assault, with 7.6 per 1,000 being assaults by intimates (Bachman and Saltzman, 1995). In contrast, in the 1985 National Family Violence Survey (NFVS) 116 women per 1,000 reported being victims of violence by an intimate (Straus and Gelles, 1990). The huge difference between the NFVS and the NCVS rates of assaults on women by intimates—the NFVS rate is 15 times higher—has been attributed to the difference in contexts of the two surveys: the NCVS questions relate to crimes; women may not view assaults by intimates as criminal, hence fail to report them in this context (Straus and Gelles, 1990).

Few data are available to determine how violence against women has changed over time or how it is related to overall rates of violence. In the United States, the rate of reported violent crime has increased dramatically in the past 20 years, from 46.1 per 1,000 in 1974 to 74.6 per 1,000 in 1993—a 61.8 percent increase (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1993). In that same time span, the rate of forcible rape reported to police increased 54.9 percent (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1993), but is not known how much of that increase may reflect increased willingness of women to report rape to the police and how much is an actual increase in the rate of rape. From 1973 to 1991, the rate of overall violence against women remained relatively constant at about 23 per 1,000 (Bachman, 1994). The NCVS did not specifically ask about sexual assaults or violence by intimates prior to 1992; after changes in the survey to specifically include such information, the reported rates of violence jumped to 43.7 per 1,000 women (Bachman and Saltzman, 1995). This change most likely reflects the change in the survey and not a sudden increase in the rate of violence against women. The NFVS found a 6.6 percent drop in the rate of intimate violence against women from the 1975 survey to the 1985 survey, although the drop was not statistically significant. In addition, the 1975 survey was conducted by face-to-face interviews and the 1985 survey was conducted by telephone: this difference may account for some of the drop in reported rates.

Although the United States has significantly higher rates of most violent crimes than most other developed countries (Reiss and Roth, 1993), rates of violence against women may be more similar. Table 2.3 shows the results of random sample surveys in a number of countries. The recent Canadian Violence Against Women Survey found that 29 percent of ever-married women had experienced physical or sexual violence at the hands of an intimate partner; in comparison, Straus and Gelles (1986) estimated that violence occurred in 28 percent of marriages in the United States. The Canadian survey also found that nearly 50 percent of all Canadian women had experienced at least one incident of physical or sexual assault since the age of 16 (Statistics Canada, 1994). The Canadian survey is remarkable in that it interviewed a random sample of 12,300 women who were 18 years of age and older and investigated physical and sexual violence as well as emotional abuse.

Accounting for Differences in Findings

As with all research, a variety of methodological factors can be linked to the differences in study findings. Sample composition and locale, data collection method, and question construction and context are among the most important methodological differences in U.S. studies.

Study samples vary widely. Although some include large numbers of African Americans (George et al., 1992; Wyatt, 1992) or Hispanics 3 (Sorenson et al., 1987; Kantor et al., 1994), most focus on European American (white) populations. With a few exceptions (e.g., George et al., 1992), most studies were conducted with urban residents. Given differences in the geographic location, age, and ethnic composition of the samples, one would not expect similar prevalence estimates.

Data collection methods also vary across the studies. Paper-and-pencil self-report instruments, once thought to be preferable because they allow for anonymity, have the lowest participation rates and produce the lowest prevalence esti-

mates of adult sexual assault (Brickman and Briere, 1984; Hall and Flannery, 1984). Telephone interviews have been shown to be a substantial improvement over paper-and-pencil surveys because some rapport between the interviewer and the woman can be established and because more detailed and specific information can be collected. Face-to-face interviews, the most costly data collection method, are generally preferred for the investigation of sensitive topics, such as violence in intimate relationships, because they allow for the greatest interviewer-respondent rapport. Sexual assault prevalence rates obtained in studies that gathered data through in person interviews are generally higher than those obtained in telephone interviews; those rates, in turn, are generally higher than the rates obtained in paper-and-pencil surveys (Russell, 1982; Hall and Flannery, 1984; Kilpatrick et al., 1985; Wyatt, 1992).

Definitions of violence against women vary from study to study. Some studies of sexual assault were limited to rape (e.g., Essock-Vitale and McGuire, 1985); others included physical contact in addition to rape (e.g., Wyatt, 1992); and still others used a very broad definition that included noncontact abuse (e.g., Sorenson et al., 1987). Given the discrepancy in definitions used to assess the phenomenon, differences in prevalence rates are to be expected.

Multiple, behaviorally specific questions are associated with greater disclosure by study participants. Studies of sexual assault that use a single screening question (e.g., ''Have you ever been raped or sexually assaulted?") no matter how broad it is (e.g., Sorenson et al., 1987) obtain lower prevalence rates than studies that use several questions that are behaviorally specific (e.g., "Did he insert his penis into your vagina?") (e.g., Wyatt, 1992). Asking directly about sexual violence does not appear to offend study participants. In one community-based survey (Sorenson et al., 1987), a number of respondents talked about their assaults for the first time when responding to a direct question by the interviewer. Also, consistent with decades of social science research that docu-

TABLE 2-3 Representative sample studies of violence against women in other countries

|

Countries & Author(s) |

Sample |

Sample Type |

Findings |

|

Barbados Handwerker, 1993 |

264 women aged 20-45 243 men aged 20-45 |

Islandwide national probability sample |

30% of women battered as adults |

|

Belguim Bruynooghe et al., 1989 |

956 women aged 30-40 |

Random sample of 62 municipalities |

3% experienced serious; violence; 13% experienced moderately serious violence; 25% experienced less serious violence |

|

Canada Statistics Canada, 1993 |

12,300 women over age 18 |

Random national sample |

25% of women (29% of ever-married women) experienced physical or sexual violence by a male partner |

|

Canada Brickman and Briere, 1984 |

551 adult women |

Representative of city of Winnipeg |

6% experienced rape and 21% sexual assault |

|

Chile Larrain, 1993 |

1,000 women aged 22-55 |

Stratified random sample in Santiago |

60% experienced abuse by male intimate; 26% experienced severe violence in relationship for at least 2 years |

|

Colombia PROFAMILIA, 1990 |

3,272 urban women 2,118 rural women |

National random sample |

20% physically abused 33% psychologically abused 10% raped by husband |

|

Korea, Republic of Kim and Cho, 1992 |

707 women and 609 men who had been with partner at least 2 years |

Three-stage, stratified random sample of entire country |

37.5% of wives report being battered by husband in past year |

|

Malaysia Women's AID Organization, 1992 |

713 women over age 15 508 men over age 15 |

National random sample of peninsular Malaysia |

39% of women physically beaten by a partner in 1989 |

|

New Zealand Mullen et al., 1988 |

349 women |

Stratified random sample selected from electoral rolls of five contiguous parliamentary constituencies |

20% physically abused by partner |

|

Norway Schei and Bakketeig, 1989 |

150 women aged 20-49 |

Random sample selected from census data in Trondheim |

25% physically or sexually abused by male partner |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Heise et al. (1994:6-9). |

|||

ments similar patterns with regard to sensitive topics, respondents in surveys were more likely to refuse to answer questions about income than they were to refuse to answer questions about sexual assault.

Prevalence estimates are also related to the context in which questions about sexual or intimate partner violence are asked. For example, the NCVS recently was amended to ask directly about sexual assault. Although such a change is an improvement over previous NCVS practice (to clearly define events such as robbery and burglary but not to name or directly ask about sexual assault), asking about sexual or intimate partner violence in the context of a survey about crime requires the respondent to define her experience as a criminal act (e.g., Koss, 1992). Research consistently shows, however, that women often do not define experiences that meet the legal definition of a rape as a rape (e.g., Koss, 1988), so they may be unlikely to respond affirmatively to questions about sexual assault that are asked in the context of a survey about criminal acts.

The context of the data collection is important in another way: women are known to be less likely to reveal incidents involving their male intimates, a common assailant according to survey research. There are a number of reasons for this phenomenon. Women may believe assaults by an intimate are family matters that should not be disclosed; they may fear losing their children should the violence become known; they may have concerns about involving the criminal justice system if the violence becomes known; and their assailants may be nearby at the time of the interview.

Like investigations into other sensitive topics (e.g., child sexual abuse; see Wyatt and Peters, 1986), most investigations have tried to reduce the differences between interviewers and study participants. One study that included both male and female interviewers and male and female respondents (Sorenson et al., 1987) found that the sex of the interviewer had little effect on prevalence estimates. Responses may vary on more subtle matters, however, and the issue of

interviewer-respondent similarity on sociodemographic characteristics, such as gender and race, has not been deeply investigated.

Using the Available Data

Policy decisions—such as how many resources to allocate to service delivery—require solid data about the incidence and prevalence of violence against women. Rather than viewing the discrepancies in prevalence estimates as a problem, the range of findings may be very useful to decision makers. For example, differing estimates on the prevalance of sexual assault research results that are related to methodological differences, can be used for different purposes. Research investigations that ask directly about sexual assault (and which obtain relatively low prevalence rates) ascertain the number of women who are willing to label themselves as survivors or victims of sexual assault and, therefore, who might seek sexual assault services. At the same time, it is important to estimate the number of women whose experiences are legally defined as sexual assault although they themselves might not define them that way: research indicates that those women use health services more frequently than women who have not been sexually assaulted, even when their health status and health insurance coverage are nearly identical (Koss et al., 1991). Thus, the "true" prevalence of violence against women may be less important for policy and other decision makers than understanding the methodological differences that resulted in various estimates.

Recognizing the commonalities in study findings of various investigations is critical to both policy and research. Research consistently documents that men known to women are those most likely to assault them (whether physically or sexually) and that young women are at high risk. These consistent findings suggest that scarce resources designated for men's violence against women should be allocated not to "stranger danger," but to the problem of violence by inti-

mates and acquaintances. The research indicates the relative importance of preventing violence against young women.

Data Gaps

Although some policy decisions can be based on existing research, improving estimates of the rates of violence against women is important for a number of reasons. Without solid baseline rates for the general population and for various groups within the population, it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of interventions, particularly preventive interventions and interventions aimed at community-wide change. Good incidence and prevalence data—though they may measure different phenomena—are also important for the allocation of service resources. A number of substantial gaps exist in the knowledge base.

First, there is relatively little information about violence against a growing segment of the nation's population—women of color. Second, research on violence against women has advanced knowledge along categorical lines (i.e., sexual assault, physical assault) rather than on what are believed to be patterns of victimization that include multiple forms of violence (e.g., Yoshihama and Sorenson, 1994). Third, studies have focused primarily on the victims, not the offenders, so there is little information on rates of perpetration. Estimates can be made of the number of women likely to experience sexual assault or intimate violence at sometime in their lives, but there is a lack of data with which to estimate the lifetime prevalence of violence perpetration. The scope of perpetration has implications for designing preventive interventions.

The studies conducted to date present a complex picture of ethnic differences in violence against women (Sorenson, 1996). National survey studies suggest that African Americans are more likely than white Americans to report physical violence in an intimate relationship (Straus and Gelles, 1986; Cazenave and Straus, 1990; Hampton and Gelles, 1994; Sorenson et al., 1996). However, how much of the variance

may be explained by socioeconomic factors and how much by cultural factors remains unclear and requires further study. Studies that included Hispanics showed contradictory conclusions. Hispanics were reported to be at higher (Straus and Smith, 1990), similar (Sorenson and Telles, 1991), or lower (Sorenson et al., 1996) risk than non-Hispanic whites for physical violence in marriage. It is possible that this range of findings is due to sample differences, study contexts, and different data collection methods. It is also important to consider intragroup differences: for example, one study of four Hispanic groups—Puerto Rican, Mexican, Mexican-American, and Cuban—found prevalence rates for wife assault varied among them (Kantor et al., 1994). In-person interviews with representative samples of women reveal little difference in sexual assault prevalence between African American and white women (George et al., 1992; Wyatt, 1992). By contrast, unlike the findings for physical violence, studies have found Hispanic women (mostly of Mexican descent) to be at significantly lower risk of sexual assault than their non-Hispanic white counterparts (Sorenson et al., 1987; Sorenson and Telles, 1991). However, a substantial and consistent proportion of sexual assaults, regardless of respondent ethnicity, are perpetrated by the woman's male intimate (Sorenson et al., 1987; Sorenson and Telles, 1991; George et al., 1992; Wyatt, 1992).

There are no survey studies, to the panel's knowledge, of Asian American women's experiences of intimate violence. Such research is important because, according to Ho (1990:129): "traditional Asian values of close family ties, harmony, and order may not discourage physical and verbal abuse in the privacy of one's home; these values may only support the minimization and hiding of such problems." Moreover, we have few data on different Asian and Pacific Islander populations, despite prevailing differences among these subgroups in terms of culture, value systems, immigration history, and other factors.

There is also limited information on the prevalence of

violence against women in American Indian and Alaska Native communities. There may be significant intertribal differences with the tremendous diversity in tribal cultures and over 250 recognized tribes, 209 Alaska Native villages, and 65 communities not recognized by the federal government (Norton and Manson, 1996). There are reports that domestic violence was rare, at least in some tribes, prior to contact with Europeans (Chester et al., 1994). It is possible that traditional family structures and social and religious functions may have served as protective factors.

Recent immigrants often are not represented in survey samples because of language and cultural barriers, immigrants' fears of officials and deportation, and fear that applications for relatives to immigrate to the United States might be affected (Chin, 1994). One study that examined immigrant status (i.e., whether the respondent was born in the United States) in association to physical or sexual assault by intimates offered surveys in either Spanish or English and found that persons born in Mexico evidenced a much lower risk of both physical and sexual violence in their intimate relationships than their U.S.-born Hispanic counterparts (Sorenson and Telles, 1991). These differences in risk patterns were not identified in two other studies of Latinos (Straus and Smith, 1990; Sorenson et al., 1996), in no small part because relatively recent immigrants were not likely to have been sampled since neither of these latter two studies interviewed anyone in Spanish. Diversity in the primary variable of interest, culture, is attenuated when monolingual non-English speaking populations are excluded.

There is a further methodological problem. Most studies have used measures and instruments developed on Anglos and simply applied them to members of other ethnic groups, for whom the instruments' validity is unknown. There may be differences in the intent of a question and a respondent's interpretation related to patterns of expression and idioms that may vary across cultures. This may explain, in part, the lack of consistency of results across studies. Clearly, unique

cultural manifestations of violence against women cannot be identified if such experiences are not measured. The failure to include women of color in the development of instruments designed to assess violence against women has left the field with a major gap in the data.

In addition to data gaps about the prevalence of violence among minority women, there is also little conceptual understanding of how structural factors relating to race or ethnicity and socioeconomic status interact with gender to create the specific context in which violence is experienced (Crenshaw, 1991). These conceptual gaps can sometimes lead to oversights and omissions that can lead to policies that unintentionally exacerbate some women's vulnerability to violence. For example, immigration policies that required immigrant women to remain married to a resident spouse for 2 years before they could receive permanent residence status forced some women to remain in violent situations. Although there is anecdotal evidence that language barriers, immigrant status, geographical or social isolation, and cultural insularity can influence the experience of violence and the accessibility of interventions, these dynamics have not been systematically researched.

Additionally, there is little systematic information about the intersection of different forms of violence. One could speculate that a woman who is beaten by her husband on a regular basis is likely to be sexually victimized and psychologically maltreated as well, but survey research seldom investigates the co-occurrence of various forms of violence against women. Most surveys have focused on single aspects of women's experiences of violence, such as rape or physical violence. For example, studies of intimate partner violence that neglect to ask about sexual violence may miss information on and understanding of marital rape. Case studies of battered women indicate that the most severely battered women also experience severe sexual violence (Browne, 1987).

Another source of data may be studies of women's health and behavior that include unanalyzed information pertinent

to violence against women. Identification and secondary analysis of these types of data sets could yield much information and at a relatively low cost. The inclusion of research questions pertaining to violence against women in other studies, such as those pertaining to women's health, alcohol and drug use, prenatal care, or unplanned pregnancy, could further help illuminate the context in which women experience violence and its impact on their lives. For example, existing health surveys could be amended to include questions about violence in women's lives. Research suggests that pregnant women who are battered are more likely to delay obtaining prenatal care (McFarlane et al., 1992) and to have low-birth-weight babies (Bullock and McFarlane, 1989) than pregnant women who are not battered. Cigarette smoking, alcohol and other drug intake, mental health status, and other relatively sensitive topics have been investigated in numerous studies of pregnancy. Including questions about being hit, kicked, or otherwise injured by one's male intimate may yield key information for understanding of pregnancy complications and outcomes, as well as of violence itself. Physical and sexual violence may account for some of the unexplained factors in women's health status that have been noted.

Conclusions And Recommendations

Violence against women has been recognized as an important field of scientific inquiry, and the research to date has illuminated many aspects of women's experiences with violence. However, that research has often been narrowly focused, and comparisons across studies have been hampered by methodological differences.

Definitions and Measurement

Research definitions of violence against women have been inconsistent, not only making study findings difficult to compare, but also contributing to controversy over the scope of

the problem. More consistent definitions and improved measures covering all aspects of violence against women would facilitate needed research on violence against women and improve knowledge as a basis for both research and policy.

Recommendation: Researchers and practitioners should more clearly define the terms used in their work.

Researchers, policy makers, and service providers from a wide spectrum of disciplines and fields—including public health, criminal justice, medicine, sociology, social work, psychology, and law—work on violence against women, and they need to ensure that others can understand and use their findings. The definitions need to take into account the full range of abuse experienced by women—sexual, physical, and psychological—and acknowledge the commonalities among, as well as unique aspects of, those forms of violence. Definitions that take into account the multidimensional aspects of violence against women will allow for the assessment of multiple types of violence against women in the same sample. Definitions should also specify severity, duration, and frequency of violent acts.

Recommendation: Research funds should be made available for the development and validation of scales and other tools for the measurement of violence against women to make operational key and most used definitions. The development process should include input from subpopulations with whom the instrument will be used, for example, people of color or specific ethnic groups.

There has been much controversy in the field over instruments used to measure violence against women, and the paucity of validated instruments is a serious barrier to improved research on violence against women. The context in which questions are asked and the wording used may influence the willingness of respondents to report violence. The context and wording of questions may also have different meanings

for different subpopulations. In fields in which few measurement instruments are available, determining construct validity (the extent to which the association between a measure and other variables is consistent with theoretical or empirical knowledge) and concurrent validity (the extent to which a measure is related to other presumably valid measures) may be difficult. Repeated use and refinement of the test instrument, with careful attention to such aspects of measurement as format, administration conditions, and language level, may be necessary. Instrument developers may receive guidance on validity determination from the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (American Educational Research Association et al., 1995).4

After work on instrumentation, including investigations of effective questioning strategies in relevant subpopulations, funding is needed for survey studies of varying sizes and scope (including different age groups and ethnic or racial groups) to rigorously document the extent of violence against women. Although some national surveys have estimated the frequency of violence against women, few national lifetime prevalence data exist, especially for racial and ethnic subgroups and other subpopulations. Because most surveys include persons who have experienced violence and sought services, those who have experienced violence but not sought services, and those who have not experienced violence, they can investigate the range of experiences and exposures. Documentation in official records (e.g., law enforcement records, medical charts) also needs to be improved so that more research can be conducted using available records. An improvement in official records would reduce, to some degree, the need for and expense associated with investigating certain research questions in one-time studies.

Recommendation: National and community level representative sample survey studies using the most valid instrumentation and questioning techniques available to measure incidence and prevalence of violence against

women are needed. These studies should collect data not only on behavior, but also on injuries and other consequences of violence. Studies of incidence and prevalence of perpetration of violence against women are also needed. National and community surveys of other topics, such as women's mental or physical health or social or economic well being, should be encouraged to include questions pertaining to violence against women. Furthermore, identification and secondary analysis of existing data sets with respect to violence against women should be funded.

Research on Context

A consideration of the context in which women experience violence is vital to understanding the nature of the problem, as well as to the consequences to the woman, and effectiveness of interventions. There is little understanding of how such factors as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, culture, and sexual orientation intersect with gender to shape the particular context in which violence occurs. Because women's experiences differ on these dimensions, those differences must be understood and incorporated into the body of knowledge about violence against women in order to design intervention strategies. Other factors that warrant consideration include disability, religion, homelessness, and institutionalization. Investigators should be encouraged to undertake studies that examine risk factors for victimization as well as groups at risk of victimization. In other words, in addition to identifying target groups for prevention and intervention, research needs to identify elements that might be amenable to change.

Recommendation: All research on violence against women should take into account the context within which women live their lives and in which the violence occurs. This context should include the broad social and cultural context, as well as individual factors. Work should in-

clude more qualitative research, such as ethnographic research, as well as quantitative research, designed to uncover the confluence of factors such as race, socioeconomic status, age, and sexual orientation in shaping the context and experience of violence in women's lives.

Notes

-

1.

The UCR does not provide data on homicides for Hispanic or Asian Americans.

-

2.

The National Crime Victimization Survey has been well described and its limitations examined in other work; see, for example, Reiss and Roth (1993), Fagan and Browne (1994), and Koss (1992, 1993).

-

3.

The terms ''Hispanic" and "Latino/Latina" are used interchangeably in this report, following the term used in the research being reported.

-

4.

For a detailed discussion of the validity and reliability of the Conflict Tactics Scales, see Straus (1990b,c).