6

Health Care Interventions

In the last three decades, knowledge about the short- and long-term health effects associated with abuse and neglect, combined with the advocacy efforts on behalf of victims of family violence, have stimulated health professionals to focus attention on its causes, consequences, treatment, and prevention (Alexander, 1990; Chadwick, 1994). This enhanced interest has been accompanied by an increase in the number and variety of health intervention programs (Kolko, 1996a; Infante-Rivard et al., 1989). Although individual clinicians may respond to the needs of individual patients, clinical settings and public health agencies often do not address family violence as a health and social problem (Journal of the American Medical Association, 1990; Hamberger and Saunders, 1991; Kurz, 1987; McLeer et al., 1989). Several professional associations have recommended diagnostic and treatment guidelines for family violence, but health care interventions for family violence are generally not incorporated into standard medical care, health data reporting systems, or health care reimbursement practices.

In their direct contact with individual patients, who may include past, present, and future victims of family violence, health care providers have daily opportunities to screen for, diagnose, treat, and prevent individual cases of child abuse and neglect, domestic violence, and elder abuse. Estimates of the impact of family violence on the public health and the health care system indicate that family violence accounts for 39,000 physician visits each year; 28,700 emergency room visits, 21,000 hospitalizations, and 99,800 hospital days Rosenberg and Mercy, 1991). They can provide important linkages between individual health services, social support networks, community resources, and more comprehensive preventive efforts; in their roles as researchers and advocates, they can integrate their

expertise in direct patient care with efforts to expand the range of health and social services available to their patients and the general population. Health care professionals interact with the legal system and the social service system as mandated reporters, forensic examiners, and expert witnesses.

The health care system consists of two broad sectors: the medical care sector is focused on services for individuals, and the public health sector is concerned with community-based efforts to improve the quality of care for special groups, including the poor and persons with infectious diseases and chronic or debilitating health problems. The interventions described in this chapter are primarily medical interventions; they focus on individuals and the treatment of patients for injuries or illnesses, including mental illnesses, that may or may not be reported as consequences of family violence. The medical model includes interventions such as screening, diagnostic and therapeutic services, referrals for specialized services, and follow-up care to maintain the patient's health and prevent the recurrence of health disorders.

Current violence prevention efforts in the medical care system generally focus on particular populations defined by gender, age group, or type of violence. Some efforts involve system-wide approaches that include interactions between health care providers and representatives of community agencies, advocacy groups, and the media to address family violence in the general population. Prevention efforts have usually targeted individuals rather than the family unit, with the exception of services based in family practice and some mental health settings.

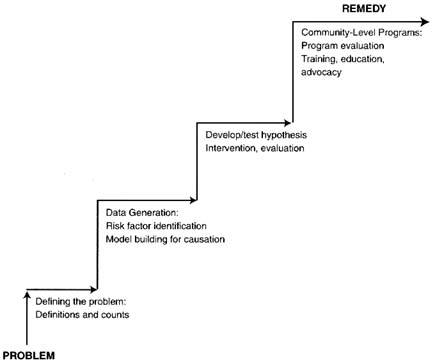

In contrast, prevention efforts in the public health system include programs and interventions to improve the health of the public or special populations within a community. In the last decade, the field has embraced violence as a subject within its mandate, and proponents have contributed new tools and perspectives to changing abusive and violent behavior and preventing its injurious consequences (Mercy et al., 1993). The formulation of violence as a public health issue dates to the 1985 surgeon general's Workshop on Violence and Public Health, convened by Surgeon General C. Everett Koop to encourage health professionals to begin to respond to the consequences of interpersonal violence (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1986). Modeled on historical successes in controlling infectious diseases, the public health approach aims to reveal underlying patterns of violence in communities, to identify individuals and groups at risk, and to highlight and control the risk factors and behaviors that are associated with child abuse, domestic violence, and elder abuse (Rosenberg and Fenley, 1992) (Figure 6-1, Table 6-1).

Oriented toward communities and prevention rather than the treatment of individuals and consequences, the public health perspective is not prominent in most of the interventions described in this book. The emphasis on proactive responses to social problems that have major health consequences has the potential to engage the public health system and individual health care providers in a

FIGURE 6-1 Public health scientific method and its role in family violence research.

SOURCE: Mercy et al. (1993). Copyright 1993, The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc., Project HOPE, http://www.projhope.org/HA/. Reprinted by permission of Health Affairs.

broad network designed to provide not only health care services but also referrals to others who can address the legal and social dimensions of family violence before harmful effects have occurred. The public health perspective also promotes the use of scientific knowledge and quality assurance and performance measures to achieve community health goals (see Box 6.A). The committee sees real value in a strong commitment to public health approaches to the prevention of family violence, although work in this area has a long way to go to establish viable prevention strategies and demonstrate evidence of their effectiveness.

The existing research on health care interventions focuses primarily on the incidence and prevalence of abuse in specific populations, the characteristics of victims and perpetrators, and the health consequences of victimization. Although attention is most often given to the immediate impact of family violence on victim use of health services and resources, the health impact of family violence can affect different stages of development over the life course, including pregnancy outcomes and fetal development, infancy, early and middle childhood,

TABLE 6-1 Public Health Strategies for Preventing Violence and Its Consequences

|

Strategy |

Description |

Intervention Examples |

|

Change individual knowledge, skills, or attitudes |

Deliver information to individuals to: —Develop prosocial attitudes and beliefs; —Increase knowledge —Impart social, marketable, or professional skills —Deter criminal actions |

—Conflict resolution education; —Social skills training —Job skills training —Public information and education campaigns —Training of health care professionals in identification and referral of family violence victims —Parenting education —Home visitation programs for young, poor, single mothers —Family therapy |

|

Change social environment |

Alter the way people interact by improving their social or economic circumstances |

—Adult mentoring of youth —Job creation programs —Respite day care —Battered women's shelters —Economic incentives for family stability |

|

Change physical environment |

Modify the design, use, or availability of: — Dangerous commodities —Structures or space |

—Control of alcohol sales at local events; —Gun laws and restrictions (e.g., in schools) |

|

SOURCE: Modified from Mercy et al. (1993). Copyright 1993, The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc., Project HOPE, http://www.projhope.org/HA/. Reprinted by permission of Health Affairs. |

||

adolescence, adult stages, and the latter stages of life. Family violence has been identified as a contributing factor for a broad array of fatal and nonfatal injuries and health disorders, including pregnancy and birth complications, sudden infant death syndrome, brain trauma, fractures, sexually transmitted diseases, HIV infection, depression, dissociation, psychosis, and other stress-related physical and mental disorders (Journal of the American Medical Association, 1990). Family violence has also been associated with numerous major social problems, including aggressive, violent, self-injurious, and suicidal behavior; teen pregnancy; runaway and homeless youth and adults; substance abuse; and delinquency and crime (Malinosky-Rummell and Hansen, 1993; National Research Council, 1993a; Widom, 1989a,b,c). Family violence has been identified as the causal

|

BOX 6.A In 1991, one of the priority areas identified in the Public Health Service report Healthy People 2000 is the need for information to guide public health policy at the state, local, and national levels and to develop common health goals that can help change social norms that may contribute toward a health problem. Among its 300 goals, Healthy People 2000, in its revised form (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1995), includes the following objectives related to family violence:

As with many of the national objectives, however, baseline and follow-up data were not available at the national level and data constraints were even more severe at state and local levels (Stoto, 1992; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1995). An Institute of Medicine report has recently proposed a community health improvement process to integrate various perspectives on the determinants of health and performance monitoring and to marshal collective resources in a community to improve the health of its members (Institute of Medicine, 1997). The process includes 12 recommended prototype indicators, including the prevalence of physical abuse of women by male partners; the number of confirmed child abuse cases reported to authorities and the percentage receiving child protective services and appropriate medical care; and the existence of protocols for health care professionals to identify, treat, and properly refer suicide attempts, victims of sexual assault, and victims of spouse, elder, and child abuse. |

link in some health and social problems resulting from cases that involve physical injuries, withholding medication, complications of forced sex, or inability to use barrier protection. Although linkages in many other areas are uncertain and often highly individualistic, the presence of family violence as a risk factor in such an expansive range of health disorders has created strong interest in identifying medical interventions to address family violence.

Evaluations of family violence treatment and prevention interventions in health care settings are not well developed in the research literature. Child maltreatment interventions are the most commonly studied services, especially mental health services and home visitation programs. Evaluations of health care provider training, identification, and screening programs are extremely rare in all three areas of family violence. Documentation of histories or reports of family violence, for either children and adults, are generally not part of medical practice. As a result, the impact of interventions on an individual's health history or on the general health of a community often is unknown.

As in social service and the legal interventions, progress in evaluating the effectiveness of health care interventions is hampered by numerous methodological and design constraints. There are very few quasi-experimental or experimental studies; those that exist do not use control groups or other hallmarks of rigorous design. Rather, they are essentially individual program descriptions, with information about patient demographics and characteristics and caseload and process measures. One important exception to this observation is the set of studies that have been conducted on home visitation interventions, which are usually based in a community public health agency. These studies are some of the few evaluations of family violence interventions to use randomized assignment, rigorous assessment measures for maternal and child well-being, and lengthy follow-up periods (15 years in one study).

This chapter reviews health care interventions and the available evaluations of them, first for child maltreatment, then for domestic violence, and finally for elder abuse. As discussed in Chapter 1, our decision to treat interventions according to their institutional settings necessitated somewhat arbitrary categorizations. The discussion of certain interventions would be equally appropriate in the chapters on social services or the legal system, but we have categorized as health related all interventions that occur primarily in a health care setting. The chapter includes brief descriptions of some interventions of great interest in the field that are in the early stages of development but have not been evaluated.

Child Maltreatment Interventions

Evidence of child maltreatment appears to health care providers as multiple and recurrent injuries, injury histories inconsistent with physical findings, and injuries inconsistent with children's developmental capability to sustain them on their own (examples of the latter are a 2-month-old infant with a fractured arm

and a prepubertal child with a sexually transmitted disease). Health care providers are required under state law to report suspicions of child maltreatment to child protective service officials.

The response of the health care system to child abuse and neglect involves identification of maltreatment and referral of victims and perpetrators for associated health care, social, and legal services; treatment for the immediate and long-term medical and psychological consequences; and the reporting of abuse and neglect to the appropriate investigatory authorities in order to initiate protective intervention on behalf of the child. Although all children who come to the attention of the health care system and who require medical care are treated, identification and reporting of maltreatment are inconsistent and are influenced by health care providers' awareness, training, and judgment (see the discussion of mandatory reporting in Chapter 5). As a result, some (possibly many) children do not receive appropriate services and may not be viewed as at risk for future maltreatment.

Six interventions are reviewed in this section: (1) identification and screening, including the use of hospital multidisciplinary teams and the role of health care professionals as expert witnesses, (2) mental health services for child victims of physical abuse and neglect, (3) mental health services for child victims of sexual abuse, (4) mental health services for children who witness domestic violence, (5) mental health services for adult survivors of child abuse, and (6) home visitation and family support programs. The sections are keyed to the appendix tables that appear at the end of the chapter.

6A-1: Identification and Screening of Child Maltreatment1

Organizations for health care professionals have initiated training programs designed to increase knowledge for recognizing, diagnosing, documenting, and treating child abuse. The range of efforts includes integrating health care professionals into interdisciplinary multiagency teams and interventions (American Academy of Pediatrics, 1991; American Medical Association, 1992a,b, 1995); issuing guidelines for interview techniques, behavior observations, and physical examinations; and providing health care providers with information about reporting requirements and community resources for social and legal assistance to patients. Physician guides and visual diagnosis kits have been designed to assist health professionals in establishing the causes of injuries in both obvious and obscure cases of child maltreatment.

Local community-based programs that unite public health and clinical settings also serve an educational and awareness-raising role. The Preventing Abuse and Neglect Through Dental Awareness (PANDA) Coalition in Missouri, for

|

1 |

See also the discussion of mandatory reporting procedures in Chapter 5. |

example, includes state medical, public health, and social service representatives committed to educating dental professionals about how to identify and report child abuse and neglect (Missouri Department of Health, 1995).

Although evaluations have examined the impact of training about child maltreatment on the knowledge and behavior of health care providers, they have not examined links between training experiences, provider practices, service referrals, and patient outcomes. Nor have they examined the possibility that increased detection may provide diminishing returns for both child and adult victims if additional remedies are not available. As a result, the ability of health care providers and institutions to recommend appropriate care for recognized victims of family violence, monitor treatment implementation and success, and influence eventual health outcomes for children and families has yet to be adequately documented.

Table 6A-1 lists the only evaluation of an identification and screening program that meets the committee's criteria for inclusion. It compared child health and rates of reported maltreatment outcomes for two groups of high-risk mothers using a screening device and a comprehensive health services program for one group and routine services for the other (Brayden et al., 1993). Although infant health improved in the treatment intervention, the comprehensive program did not alter the rates of reported abuse for high-risk mothers and was associated with an increased number of neglect reports, possibly a result of surveillance bias.

The authors attribute the failure of this intervention to demonstrate reduced rates of maltreatment in part to the possibility that the psychosocial treatment of the mothers may not have been intensive enough to offset past adverse environmental influences, even though the medical aspect of the intervention improved infant health. The authors also observe that group discussions for high-risk mothers may have been a poor choice, since it may have unintentionally facilitated poor parenting practices. This evaluation suggests that improving health care provider knowledge or behavior alone may not be sufficient to influence maltreatment outcomes if the availability and efficacy of other intervention services are not considered.

Hospital Multidisciplinary Teams

Many health care facilities use multidisciplinary teams to improve identification and case management for victims of child maltreatment identified in hospitals. These teams are generally composed of hospital administrators, social workers, physicians, nurses, and mental health professionals who perform several roles: providing medical consultation on individual cases; assisting with the psychosocial management of the family while in crisis; initiating and coordinating outpatient care and follow-up; conducting integrated case reviews with representatives from social services and legal agencies; and educating other health care providers.

The use of multidisciplinary teams has not been evaluated to assess child health outcomes. Several hospitals have now disbanded their teams because of lack of resources and smaller populations of pediatric patients.

The Health Professional as Expert Witness

In cases of physical or sexual abuse, the medical record that documents the history and physical examination of the victim may be the most important piece of evidence heard by the court. Physician statements and medical records can justify important exceptions to hearsay rules (which vary from state to state), thereby allowing the child to speak about the nature of the event, the circumstances, and the identifies of the persons involved (see also the discussion of improving child witnessing in Chapter 5). The health professional can collect, document, and present evidence of abuse; discuss the likelihood of maltreatment and possible perpetrators; and if necessary advocate for the child's safety and best interests.

In theory, the preparation and training of health care professionals regarding expert testimony can improve their effectiveness and willingness to appear in court on behalf of patients and enhance the use of the victim's medical records as evidence (Stern, 1997). Such training may also make them better witnesses for the defense as well as better prosecution witnesses. No studies have evaluated the impact of such training programs, however, and uncertainty exists as to whether they improve collaborative efforts between health professionals and the law enforcement officials, improve the prosecution of offenders and the protection of victims, or alter long-term health outcomes for children. In addition, the absence of compensation for the time and diagnostic tests that may be involved in preparing such testimony may discourage many health professionals from participating in law enforcement actions.

6A-2: Mental Health Services for Child Victims of Physical Abuse and Neglect

No consistent set of mental health consequences has been identified for children who have been maltreated (Goldson, 1987; Malinosky-Rummell and Hansen, 1993; Kolko, 1996a), although they have been reported to be developmentally delayed, have behavior disorders, and be recognizably different from their age peers in ways than cannot be attributed to physical injuries alone (Cicchetti and Carlson, 1989; Wolfe, 1987). (Note that victims of child sexual abuse are discussed in the next section.) Some children show many symptoms immediately; some show symptoms some time after the abuse; and some seem to show no visible effects of their experiences at all. Different factors may account for this variation in the emotional and mental health impact of maltreatment, including the level of parental support, cognitive-attributional perspectives, and

the presence or absence of other stressful factors in the child's environment. More research is required to investigate the variability in children's responses to their experiences in order to develop effective intervention programs (Salzinger et al., 1993).

Children who have been maltreated are typically referred to psychotherapy or counseling for a range of problems, including hyperactivity, impulsiveness, delinquency, aggressive or undisciplined behavior, noncompliance, social withdrawal, isolation, anxiety, phobias, and depression. They may receive any one or a combination of services (individual/group/family therapy and psychodynamic/cognitive-behavioral/psychoanalytic).

Table 6A-2 lists five evaluations in this area that meet the committee's criteria for inclusion. Two of the studies involved evaluations of the impact of treating social withdrawal in preschool children who had experienced or were assessed to be at high risk for physical abuse or neglect (Fantuzzo et al., 1987, 1988). The interventions were designed to enhance positive peer social interactions in a community-based day treatment center for maltreated children that integrates comprehensive counseling and education services for parents (the Mt. Hope Family Center in Rochester, New York, provided the site for each of the studies). The evaluations indicated that the treatment group in each study achieved developmental gains, enhancement of self-concept, and positive oral and motor skills that enhanced the social behavior of the maltreated children. Although the studies included a small number of participants (in one case, only four children each in the treatment and comparison groups), they are noteworthy in their assessment of the impact of the intervention across multiple domains of child functioning and their efforts to isolate critical components of the intervention strategy (for example, experimenting with adult versus peer-initiated social interactions).

Two studies by Kolko (1996a,b) involved a comparison of treatment conditions for children who had experienced physical abuse. In a comparison of two primary treatment conditions (cognitive-behavioral therapy and family therapy), both treatments appeared to reduce parental anger and force, but cognitive-behavioral therapy showed a significantly larger reduction than family therapy on these measures (Kolko, 1996a). An important observation in this study indicated that one-fifth of the cases showed heightened parental force in both the early and the late phases of treatment, suggesting a subgroup of families who were less responsive to services.

In a second study, 55 cases of physically abused, school-age children were randomly assigned to one of three groups: (1) individual child and parent cognitive-behavioral therapy, (2) family therapy, or (3) routine community services (Kolko, 1996b). Relative to routine community services, both individual cognitive-behavioral and family therapy were associated with greater reductions in child-to-parent violence and children's externalizing behavior, parental distress and risk of abuse, and family conflict and cohesion, although the three conditions

reported improvements across time on several of these measures. Although not statistically different, abuse recidivism rates in the three intervention conditions for children in this study were 10 percent (cognitive-behavioral therapy), 12 percent (family therapy), and 30 percent (routine community services); the rates for the participating adult caretakers were 5 percent (cognitive-behavioral therapy), 6 percent (family therapy), and 30 percent (routine community services). No significant differences between cognitive-behavioral and family therapy were observed on consumer satisfaction or maltreatment risk ratings at termination.

6A-3: Mental Health Services for Child Victims of Sexual Abuse

In 1994, McCurdy and Daro estimated that 150,000 sexual abuse cases were substantiated by child protective services. Interventions in these cases include counseling programs for the child victims, treatment programs for the offenders (discussed in Chapter 5), and family therapy programs (often comparable to those discussed in section 4A-1 in Chapter 4). Prior studies indicate that between 44 and 73 percent of children who are reported as victims of sexual abuse receive some form of counseling or psychotherapy related to their victimization (Finkelhor and Berliner, 1995; Chapman and Smith, 1987; Finkelhor, 1983; Lynn et al., 1988). Other studies show that between 20 and 50 percent of victims are asymptomatic at the time of disclosure (Kendall-Tackett et al., 1993). Some children remain symptom free, others develop problems at a later developmental stage (Gomes-Schwartz et al., 1990). Furthermore, for those children who do develop symptoms, the effects vary widely (Kendall-Tackett et al., 1993).

Traditional treatment of sexually abused children includes three service approaches: the lay or paraprofessional approach, which utilizes peer counseling and support groups; the group approach, which emphasizes group therapy and education; and individual counseling, which may be provided by social workers or mental health professionals (Keller et al., 1989). Treatment types include individual, family, and group interventions and what is offered depends on the child's age, level of functioning, gender, type of victimization, availability of resources in a geographic area, and the orientation of the treatment provider (Pogge and Stone, 1990; Lanyon, 1986; Keller et al., 1989). Treatment programs reflect a variety of intervention goals: to address a child's response to the abuse, to destigmatize the experience, to increase the child's self-esteem, to prevent the onset of short or long-term adverse effects, and to prevent future abuse (Kolko, 1987; James and Masjleti, 1983; Calhoun and Atkenson, 1991; Beutler et al., 1994; O'Donohue and Elliott, 1992).

Outcome measures are typically comparative measures of the victim's mental health or externalizing behaviors (sexual play with other children, self-stimulation) relative to untreated victims. Several behavioral inventories and checklists are available, although other methods, such as observations of the child at

home and at school, are also used (e.g., Downing et al., 1988). Interventions may not only address effects of past abuse but also teach children skills to avoid further abuse. Recognizing that sexual victimization can have profound effects on family dynamics and other family members, therapeutic interventions may address the nonoffending parent as well as the child victim (Deblinger et al., 1996; Oates et al., 1994).

Table 6A-3 lists seven evaluations of interventions in this area that meet the committee's criteria for inclusion. Six of these evaluations examined therapeutic interventions. Three studies compared treatment groups with no-treatment control groups (Deblinger et al., 1996; Oates et al., 1994; Verleur et al., 1986); the others compared competing treatment formats (Berliner and Saunders, 1996; Cohen and Mannarino, 1996; Downing et al., 1988). All six showed improvements in victim mental health following a variety of therapeutic interventions. The efficacy of abuse-specific treatment has been demonstrated in three studies (Cohen and Mannarino, 1996; Deblinger et al., 1996; Verleur et al., 1986).

In a seventh study, an experimental group of female adolescent incest victims who received sex education therapy in group treatment showed significant increase in positive self-esteem and increased knowledge of human sexuality, birth control, and venereal disease compared with the control group (Verleur et al., 1986). The latter finding is significant because less rigorous studies have shown that child sexual abuse victims are likely to be more sexually active than other children and therefore may have greater need for such knowledge.

A review of 29 nonexperimental studies of therapeutic interventions for child victims of sexual abuse found only 5 that demonstrated beneficial outcomes attributable to the intervention as opposed to the passage of time or some other factor outside therapy (Finkelhor and Berliner, 1995). In a similar review of the literature, the researchers were unable to assess the effectiveness of any mental health interventions for sexually abused children because of the limited numbers of studies and methodological problems (O'Donohue and Elliott, 1992). Consistent benefits of treatment for child victims of sexual abuse have been reported in clinical pre-post studies, although no specific type of therapeutic intervention has been shown to have significant impact when compared with others in experimental studies.

6A-4: Mental Health Services for Children Who Witness Domestic Violence

Whether or not they are also the victims of abuse themselves, some children who witness violence in their home or their community not only are more disturbed in their interpersonal relationships than other children, but also are at significant risk of repeating dysfunctional relationship patterns, which can contribute to a cyclic pattern of family violence (Bell and Jenkins, 1991; Zuckerman et al., 1995; Jaffe et al., 1986a,b). Some of these children show psychological or

behavioral reactions to witnessing violence similar to those of children who have been abused themselves (Fantuzzo et al., 1991; Hurley and Jaffe, 1990; Kashani et al., 1992; Osofsky, 1995a,b).

In reviewing the literature on the effects of witnessing violence in the home, retrospective studies suggest that boys who witness domestic violence are more likely to use violence against their own dating partners and wives (Hotaling and Sugarman, 1990). Girls who witness domestic violence may also be more violent in dating relationships, but such exposure does not appear to be a significant risk factor for adult victimization. Many gaps and inadequacies exist in this research area, including the absence of longitudinal studies that inhibit understanding of the interactions and pathways involved. A recent secondary analysis of a domestic violence database from the Spouse Assault Replication Program (SARP) (discussed in Chapter 5) provides valuable insights in examining the prevalence and situational characteristics of children exposed to substantiated cases of adult female abuse and additional developmental risk factors (Fantuzzo et al., 1997). The authors report that children are often involved in multiple and intricate ways in domestic disputes, beyond simply witnessing physical or sexual assaults. A sizable number of children in such households are the ones who call for help, are identified as a precipitant cause of the dispute that led to violence, or are physically abused themselves by the perpetrator.

Mental health services for children who witness domestic violence are a relatively new intervention strategy, but several preventive intervention and treatment programs have emerged as a secondary prevention strategy—one targeted to families who meet certain case criteria (Osofsky, 1997). One such program is Boston City Hospital's Child Witness to Violence Project (Groves et al., 1993; Zuckerman et al., 1995; Groves and Zuckerman, 1997). The goals of the intervention are to increase stability and safety in a child's environment, to treat psychological and developmental problems related to witnessing violence, to educate and support parents in managing marital conflict and eliminating violence, and to stimulate discussion by families about the role of violence. This program has not been evaluated.

Table 6A-4 lists two evaluations of one type of group treatment program for child witnesses that meet the committee's criteria for inclusion. These evaluations suggest that interventions for children who witness violence at home have beneficial effects, but they offer contradictory evidence as to which variables are most likely to be affected.

Following a 10-week group counseling intervention focused on a number of outcomes, interview data indicated significant gain in two areas: the children were able to report more safety skills and strategies and had more positive perceptions of their mothers and fathers (Jaffe et al., 1986b). No differences were found on their perception of their responsibility for the violence between their parents.

In contrast, a replication of the same treatment program found no significant

differences between treatment and control groups in knowledge of safety and support skills (Wagar and Rodway, 1995). Significant improvement was noted in the treated children's attitudes and responses toward anger and sense of responsibility for parents and violence in the family. The real contribution of these interventions for children who witness domestic violence remains unclear; it is also uncertain whether such interventions influence the incidence of domestic violence between adult partners.

The evaluation of future interventions of children exposed to violence is complicated by the interaction of multiple risk factors, including the violence that the child witnesses, the general home atmosphere, violence in the community, and violence that involves the child as victim. Since family violence usually operates in concert with other pathogenic influences, effective interventions require recognition of the broader context of the child's family and neighborhood environments.

Another issue for research is emerging evidence suggesting that, although some children may be profoundly affected by exposure to violence, many do not develop marked problems (King et al., 1995). Considerable literature on protective factors or resilience examines how many children exposed to extreme circumstances manage not only to survive, but also to thrive in the face of such adversity (Garmezy, 1985, 1993; Rutter, 1990). In order to develop effective prevention and intervention strategies, it is crucial to understand the processes by which some individuals remain confident and develop supportive relationships despite difficult circumstances. Future study designs, preferably longitudinal, should give equal attention to variables that may protect children and be associated with more positive outcomes (Osofsky, 1995a). Existing services (such as Head Start programs) can provide natural opportunities for collaborative partnerships between family violence researchers and service providers (including child care workers, early childhood educators, parents, and community leaders) that examine not only the problems that arise in situations in which children are exposed to domestic violence but also the family, community, and cultural strengths that provide important compensatory mechanisms in addressing the impact of such exposure (Fantuzzo et al., 1997). These opportunities can assist with the development of tools to address the hard-to-count and the hard-to-measure dimensions of family violence, child development, and family functioning, especially in high-risk environments in which young children may be disproportionately vulnerable to familial stress factors.

6A-5: Mental Health Services for Adult Survivors of Child Abuse

A positive correlation has been shown between childhood sexual abuse and mental health problems in adult life. The effects of abuse on victims may manifest themselves at different phases of the life cycle; some victims may not require, or may not have access to, mental health services until they reach adulthood.

Therapeutic interventions for adult survivors of child abuse may be delivered through individual or group therapy. Few evaluations of either approach have been done. Studies of adult victims are rare and are characterized by the same methodological problems as research on child victims.

Table 6A-5 lists the only evaluation in this area that meets the committee's criteria for inclusion. Using a randomized clinical trial design, it tested the hypothesis that different kinds of group therapy can recreate the experience of family, and in this setting adults can relearn healthy interpersonal skills (Alexander et al., 1989, 1991). Group therapy was more effective than a wait-list condition in reducing depression and alleviating distress, with differences maintained at the 6-month follow-up. Fearfulness and social adjustment were also affected differentially by the two types of group therapy used.

6A-6: Home Visitation and Family Support Programs

Home visitation and family support programs, which are usually administered by public health agencies, constitute major preventive interventions that show important promise in addressing the problem of child maltreatment. In contrast to the parenting practices and family support services discussed in Chapter 4, home visitation is offered to families at risk of child maltreatment but who have not been reported for it; home visitation seeks to influence parenting practices during critical transitions in family life.

Home visitation is a health care strategy to improve child health and development outcomes in families determined to be at risk for poor infant and child outcomes, based on risk factors of low birthweight, prematurity, young age of mother, primiparity, maternal education, poverty or low socioeconomic status, lack of maternal social support, and substance abuse (Brayden et al., 1993; Infante-Rivard et al., 1989; Seitz et al., 1985; Bennett, 1987; Brooks-Gunn, 1990; National Research Council, 1993a; Institute of Medicine, 1994). In traditional practice, home visiting programs generally begin with prenatal care for the mother and then extend through the first or second years of her child's life. Home visitors attempt to improve bonding by educating parents about children's physical, cognitive, and social development, by teaching parents more effective parenting and child management techniques, and helping them develop access to family support services and community resources. Although the primary focus is on the mother and her role as the primary caregiver, family functioning, individualized family and child needs, and the role of community are also considered. Although there are few evaluations in this area, it is one of the few interventions that have included long-term (15-year) follow-up studies (Olds et al., 1997), suggesting that home visitation can provide an important contribution to wide-spread strategy for reducing family violence.

Table 6A-6 lists the nine evaluations in this area that meet the committee's criteria for inclusion, five of which are follow-up studies of one intervention, the

Prenatal/Early Infancy Study in Elmira, New York (Olds, 1992; Olds et al., 1986, 1988, 1994, 1995). These studies reported a significant impact on certain family health-related outcomes, including: improved prenatal health behaviors, such as improved maternal diet, reduced smoking, and greater social support; increased infant birthweight and mother's length of pregnancy, including a 75 percent reduction in preterm delivery (Olds et al., 1988). The study also reported improvements in maternal personal development by stimulating continued efforts at school or in the workforce and by postponing the birth of a second child.

Evaluation indicates that the intervention also affected child health and safety. It improved the safety of the home environment, reduced the number of emergency department visits for child injuries and ingestions, and had some effect on reports of abuse and neglect. In the highest-risk group—poor unmarried teenagers—home visitation reduced the number of subsequent child maltreatment reports during the first two years of their infant's life to 4 percent for the treatment group compared with 19 percent for the control group. This decrease during the first two years of their infant's life is linked by the researchers to improvement in parent's knowledge, parenting skills, and bonding with infants.

Four years after the completion of the intervention, however, no difference existed between the treatment and control groups in their behavioral and developmental outcomes or the rates of child abuse and neglect (Olds et al., 1994). This finding has been attributed to selection bias in the original sample—home visitors and other service personnel who continued to have contact with the mothers in the treatment groups may have been more sensitive to and more likely to report signs of child maltreatment that would otherwise not come to the attention of child protection agencies. A 15-year follow-up study of the long-term effects of the original intervention indicated that the prenatal and early childhood home visitation program showed positive results, including a reduction in the number of subsequent pregnancies, the use of welfare, child abuse and neglect rates, and criminal behavior on the part of low-income, unmarried mothers (Olds et al., 1997).

During the time between the first and second evaluations, the program evolved from a high-intensity demonstration and research study into a community services program administered by local governmental offices. During this transition, changes occurred in the program definition, target audience, educational training of the provider, extent and coordination of services, and caseload per home visitor (Institute of Medicine, 1994), which may have diluted the overall impact of the original design of the intervention (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1990).

The Elmira project was replicated in Memphis, Tennessee, in a largely low-income African American population (Olds et al., 1995). After two years of project implementation, positive outcomes were reported in interim measures associated with child maltreatment, but the children were still too young to provide any significant data on rates of reports of abuse or neglect. In the Memphis study, women reported fewer attitudes associated with child abuse (lack of empathy

for children, a belief in physical punishment to discipline infants and toddlers). At 12 and 24 months of the project, the homes of nurse-visited women were rated as more conducive to healthy families than those of the control group.

The Healthy Start program, administered by the Hawaii Department of Maternal and Child Health, is a second model of home visitation; it began in 1985 as a 3-year demonstration project and became a state program in 1988. The Hawaii program offers parent education and support as well as counseling and support in gaining access to such community resources as housing, financial assistance, medical aid, nutrition, respite care, employment, and transportation.

Initial data on the effects of the Hawaii Healthy Start program suggest that it has a positive impact on reducing child abuse and neglect; two evaluations of the program are under way but have not yet been completed. The National Committee for Prevention of Child Abuse is conducting a clinical trial with high- and low-risk families randomly receiving home visits or no treatment, but the evaluation study has not yet been published. Outcomes to be monitored include parental functioning, child physical and cognitive development, parent-child interactions, use of formal and informal community supports, and child abuse rates as measured using standardized psychometric instruments. This evaluation will examine program features such as the use of paraprofessionals as home visitors, methods for determining service intensity and duration, and methods for identifying target populations and delivering the most effective home care. The study will provide recommendations to over 25 states that have demonstrated an interest in replicating the program. A second evaluation of Healthy Start is being conducted at Johns Hopkins University but has not yet been published.

In response to early reports that home visitation may improve family functioning and child health, some researchers have concluded that the statistical evidence is not sufficient to support the efficacy of nurse visitation programs on child abuse events or child development and well-being for all children (Infante-Rivard et al., 1989). Variations in the levels of service provision and family compliance, difficulties in the measurement of abuse, and broader intervening psychosocial and socioeconomic factors that affect families make the current research difficult to interpret. Reliance on official reports as measures of child abuse and neglect may underestimate the true incidence or prevalence of such events. Surveillance bias is another methodological problem, since the homes to which health professionals have routine access may be more likely to be reported for abuse or neglect than homes that are never visited.

Despite the methodological difficulties and uncertainties about the duration of program impact on preventing child maltreatment, home visitation remains one of the most promising interventions for prevention of child abuse or neglect; there is some indication of its success with families at risk, and it would be useful to compare its benefits as a secondary (targeted) or a primary (provided to all) strategy. An important consideration is the issue of cost, since the provision of

health and social services to a large number of families in their homes over a lengthy period can be expensive.

We describe below a number of projects that have not yet been evaluated.

Healthy Families America. A new initiative for abuse prevention, called Healthy Families America, is based on the Hawaii Healthy Start program. At present, it exists as a consultation service to communities that are planning state or local home visitation programs. Its goal is to encourage the development of a universal system for parent education and support, including home visitation services for families who request additional support (Bond, 1995). Although Healthy Families America has not yet been evaluated, the program has established a research network to assess the implementation of the intervention.

Bright Beginnings. In 1995 the state of Colorado initiated the Bright Beginnings program to provide universal, voluntary home visitation by community volunteers from birth through age 3 weeks. The intervention is designed to foster positive child social and health outcomes, to reduce the incidence of child maltreatment, and to provide prenatal care for every pregnant woman in the state by 1998. The program has not been evaluated.

Anticipatory guidance at well-baby visits. Most families do not have access to home visitor services. Most new babies and their mothers are seen in the health care setting for a prescribed routine of well-care visits, which may provide many opportunities to offer the same kinds of prevention strategies as home visitation. This strategy has not yet been evaluated, and its comparative strength relative to home visitation or other community family support services is not known.

Domestic Violence Interventions

The consequences of domestic violence may be one of some women's most significant health problems. Entry into the health care system serves as a common point of intervention for battered women (Parsons et al., 1995; Commonwealth Fund, 1996; American Medical Association, 1992c). Battered women seek extensive medical care over the life course; domestic violence is one of the most powerful predictors of increased health care utilization (Bergman and Brismar, 1991; Koss et al., 1991; Felitti, 1991). Recent studies indicate that between 2 and 14 percent of women seeking medical services had experienced domestic violence in the past 1-12 months; a quarter of these cases had experienced severe abuse involving more than four incidents over the last 12 months (Abbott et al., 1995; McCauley et al., 1995; Gin et al., 1991). The lifetime prevalence of domestic violence reported in one study was over 50 percent; 16.9 percent of the women seeking health services were still with the partner who had abused them (Abbott et al., 1995).

The physical consequences of domestic violence include acute injuries as

well as chronic injury, chronic stress and fear, intimidation, entrapment, and lack of control over health care or support systems. These consequences include a range of medical, obstetric, gynecological, and mental health problems, including chronic or psychogenic pain, chronic irritable bowel, pelvic inflammatory disease, chronic headaches, atypical chest pains, abdominal and gastrointestinal complaints, gynecologic problems, and sexually transmitted disease (American Medical Association, 1992c). The mental health consequences include posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, suicide attempts, and nonspecific disorders, such as headaches, insomnia, and anxiety (Bergman and Brismar, 1991; American Medical Association, 1992c).

Although a broad array of negative health outcomes is associated with domestic violence, a significant number of women who seek health services as a result of violent experience do not identify themselves as victims. Inadequate screening and identification of battered victims is thought to be linked to providers' lack of knowledge and awareness of battering as a significant women's health problem; lack of time, privacy, and social services resources; and frustration about victims who return to violent partners (Sugg and Inui, 1992; Warshaw, 1989, 1993; Friedman et al., 1992).

The current health care response to domestic violence is a blend of medical care, public health, and advocacy approaches. The efforts of the domestic violence advocacy community, individual clinicians, and a growing number of professional societies have generated standards of care and major initiatives to increase provider awareness, to establish and distribute clinical guidelines, and to offer strategies for improving institutional responses to domestic violence. Many professional societies, including the American Medical Association, the American Nurses Association, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Association of American Medical Colleges, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Nurse-Midwives have generated standards of care relevant to domestic violence. Innovative hospital-based advocacy programs are increasing in number, and medical and nursing programs are beginning to integrate family violence materials into their standard curriculum (Warshaw, 1996).

In the sections that follow we review two types of interventions for battered women: (1) screening, identification, and medical care responses and (2) mental health services. The sections are keyed to the appendix tables that appear at the end of the chapter.

6B-1: Domestic Violence Screening, Identification, and Medical Care Responses

2Much of the health care system's response to domestic violence focuses on screening and identification. Despite widespread recognition of domestic violence as a public health problem in the 1990s, many clinicians have difficulty integrating routine inquiry about domestic violence into their day-to-day practice. The reluctance of health professionals to ask questions about domestic violence is associated with several factors, including close identification of the practitioner with the patient, especially among female clinicians who have personal histories of abuse; fear of offending patients; lack of training and knowledge about appropriate interventions; inability to control the situation or cure the problem; lack of time to deal appropriately with abuse; and lack of coverage or reimbursement for referral or recommended services (Tilden et al., 1994; Sugg and Inui, 1992). Training and institutional reform efforts are now under way to address these factors and to develop strategies for social change that can integrate public health and advocacy-based principles into traditional medical care to enhance the prevention of domestic violence (Warshaw, 1993, 1996). Integrating principles of prevention, safety, empowerment, advocacy, accountability, and social change into clinical care practices, however, requires attention to structural components of the health care system that inhibit optimal care as well as attention to the philosophy and process of clinical training (Warshaw, 1996). The enhancement of domestic violence training programs in health care settings also raises issues about the quality and verifiability of the added identifications and the points at which such increased case detection provides diminishing returns for both victims and health care providers.

Pregnancy is an important opportunity for abuse assessment and intervention. Screening for abuse prior to or during pregnancy may be effective in identifying patterns of family violence, due to the frequency and pattern of prenatal visits. Screening for domestic violence is usually included in outpatient clinic care rather than in private care settings, but the latter are also beginning to change. Recent studies have shown that the incidence of abuse during pregnancy is equal to or greater than other health complications for which women are routinely screened (such as gestational diabetes and preeclampsia), and that abuse has the potential for lethality for both mother and fetus (Gazmararian et al., 1996). Abuse during pregnancy has been linked to low-birthweight outcomes for infants (Parker et al., 1994; Bullock et al., 1989; Schei et al., 1991), an increased rate of miscarriage (Gielen et al., 1994), and maternal postpartum depression (associated with lack of support from a partner). It is not certain if abuse increases during pregnancy, but studies have indicated that 7.4 to 20 percent of

|

2 |

See also the discussion of mandatory procedures in Chapter 5. |

women experience abuse in the 12 months prior to their pregnancy (Campbell and Parker, 1992; Gazmararian et al., 1996; McFarlane et al., 1992). The timing and overlap between wife abuse and child abuse are cause for concern and warrant research (Straus and Gelles, 1990).

Effective and efficient use of screening in health care settings requires several key factors: awareness among health care professionals of the possibility for domestic violence in both general and clinical populations, especially in obstetrics, family practice, primary care, and mental health settings; the existence of sensitive and specific screening tools that can integrate questions about domestic violence into routine health histories; adequate training to overcome discomfort in asking and responding when patients reveal abuse experiences; and resources to facilitate referral once victims are identified.

As in the area of child maltreatment, organizations for health care professionals have initiated efforts to assist physicians in identifying and treating battered patients. In 1989 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists joined Surgeon General Everett Koop to launch a public awareness campaign. In 1992, the American Medical Association (1992a) published diagnostic and treatment guidelines for interview techniques, behavior observations, and physical examinations. In addition, health care organizations provide information to health care providers about state and federal reporting requirements, community resources to which patients may be referred for social services and legal assistance, emergency temporary custody arrangements, guidelines for testimony on abuse findings in legal proceedings, and risk management regarding legal liability.

Also in 1992, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations required emergency departments and hospital ambulatory care services to have written procedures and staff training for the identification and referral of victims of violence. For the first time, hospital accreditation was directly linked to compliance with standards for the care of patients who were battered by their partners. Since then, many state medical societies and public health departments have adopted these published standards.

Table 6B-1 lists four evaluations in this area that meet the committee's criteria for inclusion. These studies assessed the effectiveness of training programs and emergency department protocols in identifying battered women. The studies use times-series designs to examine outcome data before and after the implementation of an intervention. Using rates of identification of abused women as the outcome measure, the studies show that appropriate protocols can be developed and implemented that are specific to enhancing identification of battered women.

A study done at the emergency department of the Medical College of Pennsylvania, which serves a predominately low-income, inner-city population (McLeer and Anwar, 1989), concluded that staff training and protocols increased recognition of abused women, although the enhanced identification process was not maintained in the absence of institutionalized policies and procedures for

diagnosing and treating victims of domestic violence (McLeer et al., 1989). Using the same study design and outcome measure to evaluate an identification protocol implemented among nursing staff at a university hospital in the Northwest, a second study concluded that enhancing the knowledge and interview skills of nurses can increase the identification of battered women (Tilden and Shepard, 1987).

Another study used a prospective design for screening domestic violence victims in the emergency room setting (Olson et al., 1996). They screened all women ages 15-70 who came to a Level I trauma center using a chart modification method, adding the question, ''Is the patient a victim of domestic violence?" to the emergency department record. Two percent of women were identified as victims of domestic violence at baseline; 3.4 percent were identified during the chart modification month; and 3.6 percent were identified when an educational component involving training about the causes and impacts of domestic violence was added to the chart modification. The relative rate for identifying victims of domestic violence was 1.8 times higher when the question was asked than during the control month; the educational component did not appear to enhance identification.

These identification studies must be considered cautiously, since time-series study designs have well-known limitations, including the inability to control all variables that could influence the outcome (Campbell and Stanley, 1966). The limitation that is most significant to emergency department research is the frequent turnover in staff, which alters the proportion of staff who have undergone training during the study period. Changes in the socioeconomic and cultural environments used in these studies did not appear to alter or seem likely to influence the findings, according to the authors. However, the Olson study also highlights the importance of recognizing the limits of training and screening questions as isolated interventions. These approaches may have greater impact if they are part of a comprehensive approach designed to address domestic violence that provides ongoing reinforcement and changes in institutional cultures that can improve the quality of health care for victims of abuse.

Although they have not been completed, evaluations are currently under way for a number of other programs designed to enhance health provider responses to domestic violence. The Health Resource Center, administered by the Family Violence Prevention Fund in San Francisco, has developed a manual and a training model for teams of health care providers and advocates to improve hospital, clinic, and community responses to domestic violence. This model evolved from a growing recognition that traditional training was not sufficient to change individual provider behavior or to generate the kinds of system changes necessary to respond appropriately to victims of domestic violence. In 1994, a 3-year evaluation of it was undertaken by the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing in collaboration with the Trauma Foundation/San Francisco Injury Center and the University of Pittsburgh's Center for Injury Research and Control. A randomized trial will

evaluate the program's impact on staff attitudes, infrastructure changes and responses to victims needs, effectiveness of screening instruments, and patient satisfaction. The evaluation component of the training program, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, involves 12 hospitals in Pennsylvania and California.

Another evaluation study under way and funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention compares three hospitals in which the WomanKind program is already in place with three control hospitals in the Minneapolis area. WomanKind is a hospital-based program combining education and training with a network system for health professionals, social workers, and advocates involved in caring for domestic violence patients. The study will measure changes in knowledge, attitudes, and skills among health care providers and advocates; frequency of diagnosis and referral; patient satisfaction with services; number of repeat contacts with the program; and utilization of community services.

The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research has funded a 3-year study that is designed to help primary care providers in a managed care setting identify and treat victims of domestic violence. Health care providers will be educated about both acute and chronic presentations and consequences of domestic violence, and protocols for enhanced case management techniques will be initiated. Program effects on detecting battering and on preventing recurrences will be assessed, along with a critical analysis of program costs (Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1996). A unique aspect of this study is its ability to follow a specific patient population over an extended period of time.

Staff training programs and protocols, by themselves, do not ensure that patients will receive the services they need. Regardless of the training of medical staff, ensuring victim access to services depends on availability and accessibility of local resources, insurance coverage and financial strategies for reimbursement of medical services, and assurances of confidentiality and safety. Establishing an appropriate therapeutic plan depends not only on characteristics of providers but also on an institutional culture and community resources that support services for female victims by addressing such structural barriers as cost, reimbursement, and accessibility (Flitcraft, 1993; Warshaw, 1993).

For yet another set of interventions in this area, no evaluations are either scheduled or completed. They are, however, of interest to the field and are described briefly below.

St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital. St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital in New York City is developing a comprehensive intervention to obtain a statistical assessment of domestic violence related to medical visits; to provide victim advocates for emergency department patients; to provide referrals for counseling; and to foster cooperation among the law enforcement, criminal justice, and health care systems. This intervention has initiated universal screening of all women over 17 years of age in two emergency department facilities, using a structured protocol

and form to document domestic violence. Project outcomes have not been tested in the medical, social service, or legal settings.

AWAKE. The Advocacy for Women and Kids in Emergencies (AWAKE) program at Children's Hospital in Boston screens mothers of abused children for domestic violence in order to improve the welfare of the mothers and prevent future incidents of child abuse (Robertson, 1995). The program offers immediate risk assessment and safety planning, counseling services, support groups, and an educational program; it provides access to housing as well as legal and medical providers. AWAKE attempts, whenever possible, to keep mothers and children together and maintain the family. Multigenerational programs like this are good examples of how coordination of care and interagency cooperation can maximize resources available for patient care. They need to be evaluated to understand what components of these teams are most effective for securing services for abuse victims and improving health outcomes for both adult and child victims.

6B-2: Mental Health Services for Domestic Violence Victims

3Mental health consequences of domestic violence are significant and prompt women to seek services as frequently as do physical problems. In controlled studies, battered women are consistently found to be more depressed than other women on various instruments (Bland and Orn, 1986; Jaffe et al., 1986a). In other studies, depression was the strongest indicator of domestic violence among women seeking medical care at a family practice medical center (Saunders et al., 1993); a significantly higher prevalence of major depression existed among battered women than in the larger population under study (Gleason, 1993). Significant predictors of depression in battered women include the frequency and severity of abuse, other life stressors, and their ability to care for themselves; these were stronger than prior history of mental illness or demographic, cultural, and childhood characteristics (Campbell et al., 1997; Cascardi and O'Leary, 1992).

In mental health care settings, post-traumatic stress syndrome is widely recognized as a frequent consequence of violent victimization (Koss et al., 1994). Higher rates have been documented among battered women in shelters than in other groups of women (Gleason, 1993; Woods and Campbell, 1993). Many of the symptoms that emerge following domestic violence are included among the criteria for a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress syndrome: reexperiencing the traumatic event (nightmares and flashbacks), avoidance and numbing (avoidance of thoughts and reminders of the trauma), and increased arousal (problems in sleeping and concentrating, exaggerated startle reactions) (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). There is a strong possibility that post-traumatic stress syndrome

|

3 |

Mental health services programs for batterers are discussed in Chapter 5, since most clients are referred to these treatment programs by legal authorities following an arrest. |

is underdiagnosed by primary care providers, who tend to focus only on the obvious symptoms of sleep disorder and stress reactions.

Surprisingly few studies have investigated substance abuse among battered women. Two studies of medical emergency departments, neither of which was controlled, show an association between alcoholism and being assaulted by a partner (Stark and Flitcraft, 1988; Bergman and Brismar, 1991).

Other studies have found an association between abuse and illicit drug use (Plichta, 1996) and increased alcohol problems (Jaffe et al., 1986a; Miller et al., 1989). Studies of abuse during pregnancy have also reported an association with substance abuse (Amaro et al., 1990; Campbell and Parker, 1992; Parker et al., 1994). A key question that has not been well studied is the extent of mental health symptoms, including substance abuse, that may have existed prior to the family violence compared with problems that develop as a consequence of the violence.

Table 6B-2 lists four evaluations of mental health services for domestic violence that meet the committee's criteria for inclusion (see also the discussion of evaluations of advocacy services for battered women in section 4B-3, which include mental health measures in their assessments of the intervention). Bergman and Brismar (1991) studied whether a screening and supportive counseling intervention would decrease battered women's use of hospital services for somatic or psychiatric care. Several limitations, such as sampling bias, inadequate proxy or indicator measures, inadequate power to detect effect, and lack of information regarding other potentially confounding factors, make it difficult to draw conclusions.

Cox and Stoltenberg (1991) report significant improvement from preto post-test in assertiveness and self-esteem for a group of 9 women in a battered women's shelter who volunteered to participate in a group counseling program. The program had been developed to improve the skills needed to end violent relationships, but it did not report how many women returned to their abusers when they left the shelter.

Since a high percentage of women seen in mental health settings are unidentified battered women, the effects of different types of treatment formats (individual, group, couples) and protocols deserve rigorous evaluation to examine their impact on women who have experienced domestic violence (see also the discussion of peer support groups for battered women in Chapter 4).

The merits and advisability of couples counseling, a common form of family therapy for domestic violence offenders and victims, have received significant attention and debate (Walker, 1994; O'Leary et al., 1994). Many victim advocates believe that couples counseling programs fail to address issues of power, control, and violence used by the batterer and issues of safety, empowerment, and increased options for the victim. Although couples counseling treatment programs may be effective in some situations (when violence is stimulated by alcohol,

for example, or when it occurs at a low level), there is need for caution so that the danger to women is not increased by the therapy.

Harris et al. (1988) report as the most important result of their study that offender-victim couples are more likely to complete a group treatment program than a couples counseling program. In treatment groups, participants in the couples counseling format were four times more likely to drop out than those in the group program. All participants showed positive changes in psychological well-being, regardless of treatment group. The goal of ending violence in the relationship was achieved for 23 of 28 women who could be located for follow-up interviews, but this figure (82 percent) is suspect since the women who dropped out of treatment could not be located and may have dropped out because of an increase in violence. No difference was noted for level of violence between treatment groups. The evidence about the advisability of couples counseling as a whole is inconclusive.

In the past, research on victims of domestic violence has focused on identifying victims and the psychological consequences of battering. Efforts are now under way to shift the focus from clinical treatment to a broader set of health and safety goals designed to reduce the impact of violence and ultimately prevent its occurrence. Tensions between clinicians and victim advocates have been fostered, in part, by the lack of an integrated framework that could address both the social and psychological needs of battered women. Careful attention to project design will encourage scientific evaluation of different treatment models to assess their outcomes and relative effectiveness while ensuring appropriate delivery of needed services.

Elder Abuse Interventions

Very few programs offer interventions for elder abuse in health care settings; most that do adapt models used to prevent child abuse and neglect and domestic violence. Research in this field is in an early stage of development, and observers have noted that, as long as elder abuse is seen as tangential to geriatrics and gerontology, research on elder abuse interventions will remain undeveloped (U.S. House Select Committee on Aging, 1981). No rigorous evaluations of such programs have been published.

As noted in the discussions of child maltreatment and domestic violence, provider awareness of family violence and mandated reporting requirements do not necessarily translate into effective treatment and prevention services. Ehrlich and Anetzberger (1991) found that, although state departments of health were aware of elder abuse reporting laws, very few had implemented abuse identification and reporting practices. Particular problems arise in the field of elder abuse because the victims have the right to self-determination unless there is reason to doubt their competence to make decisions concerning their own welfare. In extreme circumstances, a hospital can authorize a protective service admission if

it decides that the elderly person, upon discharge, would not be safe back in his or her home setting; this option, although viable, can be difficult to achieve when hospitals seek to reduce economic costs or do not regard patient safety as part of their concern. Another option is to keep the elderly person in an emergency unit overnight until an intervention can be put in place in collaboration with social service or law enforcement officials, so that she or he can go home to a safe environment (Carr et al., 1986; Fulmer et al., 1992).

In this section we review three interventions for abused elders: (1) identification and screening programs, (2) hospital multidisciplinary teams, and (3) hospital-based support groups. There are no evaluations in this area that meet the committee's criteria for inclusion; the sections that follow are based on descriptive literature.

6C-1: Identification and Screening

Guidelines for the detection and treatment of suspected elder abuse have been published by the American Medical Association (1992d). Although 42 states now have reporting requirements for elder abuse, few hospitals have established adult protective teams.

In Seattle, Harborview Medical Center has developed an elder abuse detection and referral protocol for all geriatric disciplines (Tomita, 1982). The protocol includes medical history, presentation of signs and symptoms, functional assessment, physical exam, caregiver interview, collateral contacts, and case plans. Program services include client or caregiver service intervention, staff training, referrals to community services, and case follow-up (Quinn and Tomita, 1986).

6C-2: Hospital Multidisciplinary Teams

Hospital multidisciplinary teams are also used in elder abuse cases. The San Francisco Consortium for Elder Abuse Prevention, for example, consists of representatives from a variety of professions and settings, including case management, family counseling, mental health, geriatric medicine, civil law, law enforcement, financial management, and adult protective services. The team meets monthly to review and assess multiproblem, multiagency cases of elder abuse (Wolf and Pillemer, 1994).

Regulations for protective services in Illinois require that any protective services program serving an area that includes 7,500 or more people age 60 and older have a multidisciplinary team that represents protective services, medical care, law enforcement, mental health, financial planning, and religious institutions. Special training programs regarding elder abuse are also available in many communities for those who must respond to the needs of the elderly as health professionals, social service personnel, or caregivers.

6C-3: Hospital-Based Support Groups

Following the model of existing hospital-based support groups for families affected by diseases of the aged such as Alzheimer's, for the caregivers of elderly relatives, and for abused elders themselves (Wolf and Pillemer, 1994), support groups are intended to provide information and social support to minimize frustrations and tensions that may lead to abusive or neglectful behavior. Although descriptive data are available for many support group efforts, they often lack standards or outcomes against which to measure their effectiveness, and they do not assess the effects on the community.

The integration of elder abuse health interventions into the broad network of support services for the elderly sponsored by the Older Americans' Act and the federal Administration on Aging represents a promising approach that deserves further consideration in the treatment and prevention of elder abuse. An integrated approach allows health professionals to become part of a community effort focused on early recognition and responses that can be sustained in the absence of a crisis. Yet such initiatives, whether specific to elder abuse or to generally improve the lives of older people, are notable for their lack of measured effectiveness.

Conclusions