7

Comprehensive and Collaborative Interventions

Social service, law enforcement, and health care professionals have consistently noted that family violence is often only one aspect of the troubled lives of individuals and families who come to their attention. Family violence often occurs in a social context that includes substance abuse, homelessness, poverty, discrimination, other forms of violence, and mental disorders. Researchers and service providers have also recognized that protective factors are often in place in these same communities that mitigate problems for the majority of residents. The presence of multiple risk and protective factors in the physical and social environments of those who experience family violence is receiving increased attention in the design of treatment and preventive interventions (National Research Council, 1993a,b, 1996). Recent theories have emphasized the importance of interactions among family violence, neighborhood environments, and the broader social culture on a range of factors, such as poverty, unemployment, discrimination, and community violence, that may contribute to, or inhibit, family violence.

Three separate but complementary initiatives have emerged to address the complex interactions of risk and protective factors, multiple problems, and environmental effects on family violence: (1) service integration, (2) comprehensive services focused on separate problems that share common risk factors (also called cross-problem interventions), and (3) community-change interventions that target social attitudes, behaviors, and networks. Although the overall goals and characteristics of these three initiatives are similar, they use different strategies in seeking to accomplish change and to improve the quality and range of family violence prevention, treatment, and support services in community settings. The first focuses primarily on using existing services more effectively within a community;

the second responds to the needs and strengths of the whole person or family; and the third addresses the community or society itself as the subject of the intervention.

Experience with these initiatives is relatively recent, and research in this area is still largely descriptive. This early works indicates that

- the array of models that has emerged in the last decade are characterized by innovative and experimental approaches to service delivery;

- the emphasis on comprehensive (cross-problem) and collaborative (cross-sector or multiagency) approaches has attracted substantial interest and enthusiasm by community leaders and public and private agencies that sponsor family violence treatment and prevention programs;

- service integration efforts that go beyond agency coordination into the realm of collaboration and resource-sharing require extensive time, resources, leadership, and commitment by the participating agencies; and

- the creation of new organizational units, service strategies, and communication, information, and decision-making systems may be required to implement these initiatives.

Few evaluation studies exist to demonstrate whether comprehensive or collaborative approaches are more effective than traditional forms of service delivery in improving the outcomes of clients and communities. In many communities, the experimental initiatives often complement or extend traditional agency services rather than replace them, making it difficult to isolate the effects of the new approaches. The committee found no evaluations of any interventions discussed in this chapter that meet its criteria for inclusion; we do, however, raise key issues about the methods that should be used in studies of their effectiveness.

In this chapter, we describe what is known about service integration and cross-problem interventions that go beyond individual agencies and take the form of coordinating councils, task forces, multiagency programs, resource centers, and wraparound services. We also discuss community-change initiatives that are designed to shift the balance of power between service providers and community representatives and to foster new approaches that respond to particular needs or objectives as defined by a local community.

Types Of Interventions

Service Integration Initiatives

The hallmark of service integration is collaboration within or between health, law enforcement, and social service agencies. Tremendous diversity characterizes the structure, style of operation, funding sources, and settings in which service integration interventions operate. They do, however, share the goal of

enhancing the quality and design of services focused on discrete aspects of child maltreatment, domestic violence, and elder abuse by

- increasing service provider awareness of the multiple needs and complex histories of victims and offenders;

- identifying opportunities for integrating service plans to reduce duplication and inefficiency; and

- enhancing victim safety and diminishing the frustration and harm that can occur when victims are asked to describe a traumatic incident or relationship on multiple occasions in various institutional settings.

Some authors have characterized service integration as an evolutionary and hierarchical process (Swan and Morgan, 1993). The first level consists of informal cooperation, the second level involves interagency coordination and more formal utilization of existing resources, and the third level involves collaboration in which the participating agencies share common goals, mutual commitments, resources, decision making, and evaluation responsibilities. In some communities, for example, existing agencies are not prepared to embrace a true partnership but may share organizational resources with other programs through task force or coordinating committee efforts. Other communities have established a separate agency that provides a central physical location and organizational system supported by borrowed personnel from cooperating agencies and programs. Examples of the latter are the child advocacy centers that have emerged in numerous localities to assist with the identification, treatment, and documentation of child maltreatment, particularly child sexual abuse. Movement across the different levels of service integration is often uneven and is vulnerable to political and administrative factors that influence the integration effort and resource base of the participating agencies.

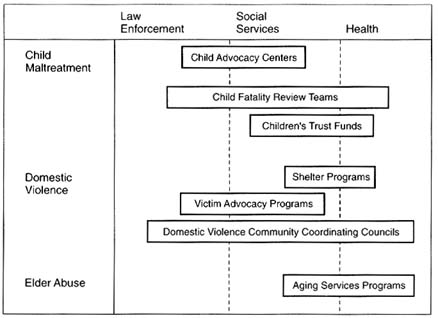

New programs can emerge that combine services across different types of violence or across institutional domains (Figure 7-1). But separate programs are not always necessary. Depending on the resources available in a particular program, victim advocates can provide their clients with legal assistance and social service referrals to counseling programs, emergency shelter, and child care regardless of their institutional setting.

Comprehensive Services for Multiple Problems

Comprehensive services seek to improve the quality and impact of service delivery by responding to the multiple problems faced by troubled families in a single service setting. Such problems include violence in the home, substance abuse, inadequate housing, juvenile crime, school dropout, physical and mental health disorders, and unemployment. These efforts have been characterized as dealing with the whole victim or the whole family.

FIGURE 7-1 Examples of service integration initiatives.

SOURCE: Committee on the Assessment of Family. Violence Interventions, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 1998.

In some cases, a specialized unit is created to coordinate and administer a broad range of services; in others, an existing agency assumes a lead role. The administrative style and setting of a comprehensive services program may affect its acceptability to affected parties as well as its overall effectiveness. Comprehensive services are not often designed to significantly change the menu of services available to victims in a given community, but rather to improve client access to existing services and to enhance agency awareness of client needs, case histories with different service systems, and community resources and expectations. In some cases, especially in the area of violence prevention, these initiatives also seek to influence individual behavior and community attitudes about violence through outreach and public education.

Community-Change Interventions

Community-change interventions involve shifting the locus of power and authority from centralized structures to the level of neighborhoods and community task forces; in achieving this goal, they often synthesize fragmented and categorized service systems (Connell et al., 1995; Kahn and Kamerman, 1996).

They attempt to create social networks in deprived communities that will enable local residents to exercise more power or autonomy in choosing or influencing the types of services available to them (Connell and Kubisch, 1996). Reform of political and social institutions is the primary focus of these interventions.

Community-change interventions are not the same as community outreach, although such efforts may overlap. The latter reflects a concern for community representation, local participation, and cultural diversity in order to improve service delivery, but it does not seek to achieve social change through political and social reforms.

The emphasis on community approaches as a general social strategy to support families and protect children has historical roots that span at least a century. The settlement houses that characterized the liberal reform movements of the nineteenth century, such as Hull House in Chicago, sought to serve a wide range of family needs in a neighborhood context (Halpern, 1990). Staff who lived in the settlement houses worked to establish a center that could spread the culture, values, and resources of mainstream middle-class America among poor and immigrant populations (Garbarino and Kostelny, 1994). These early efforts can be seen as precursors of modern victim advocacy programs, parent education programs, home visitation, battered women's shelters, and other family support services that seek to develop a national prevention strategy for family violence.

Other precursors to comprehensive community services include neighborhood-based projects to combat juvenile delinquency in the 1930s and the 1950s and the community action and model cities programs established during the war on poverty of the 1960s. Perhaps the most familiar examples of community-change interventions are the community development corporations of more recent decades (O'Connor, 1995; Halpern, 1994).

Interventions associated with this approach seek to create changes in social structures and networks on the assumption that these will lead to more responsive institutional and individual behaviors, as well as the creation of new resources that will improve the outcomes of residents and families in the community. Community-change interventions are often viewed as an instrument of progressive social reform, designed to engage multiple community resources in common efforts to foster social well-being rather than dividing the community into separate groups that focus on particular problems. This type of intervention also seeks to empower clients to gain access to services that may be scarce or located in inconvenient locations.

Examples Of Comprehensive And Collaborative Interventions

The three types of community-based interventions discussed above include fatality review teams, child advocacy centers, coordinated community responses to domestic violence, family support resource centers, substance abuse and domestic

violence treatment programs, community interventions for injury control, settlement houses, and shelters.

It is important to reiterate that these interventions have not been evaluated using control groups, and thus their effects on family violence remain undocumented. The committee presents briefs summaries of innovative efforts in order to highlight insights into the potential benefits, as well as the challenges, of these approaches. Many of these interventions contain elements of service integration, comprehensive services, and community change as described in the earlier sections of this chapter. The variation in each type of program and the lack of in-depth case studies that could describe their basic goals and methods of operation make it difficult to characterize them in more precise terms at this stage of their development.

Fatality Review Teams

It is estimated that 2,000 children die each year as a result of abuse or neglect by caregivers (Durfee, 1994). Half the fatalities identified as ''fatal child abuse" or "homicide by caregiver" involve children less than 1 year old (Christoffel, 1990). Child fatality review teams are intended to provide a systemic, multidisciplinary means by which several agencies can integrate information about child deaths in order to identify discrepancies between policy and practice, deficiencies in risk assessment or training practices, and gaps in communication systems that require attention. Since their inception in Los Angeles in 1978, child fatality review teams have emerged in 21 states to address the issue of severe violence against children and infants.

Some jurisdictions regard the most important outcome of child fatality review teams as the protection of siblings in the violent family; others emphasize the improvement of child protection efforts through better coordination and long-term collection of information. Emphasis is placed on the accurate classification of child deaths as homicides to decrease the number of homicides misidentified as accidental death, death by unknown cause, and sudden infant death syndrome (Lundstrom and Sharpe, 1991; Durfee et al., 1992). Improvements in the classification of child deaths are also thought to contribute to the collection of evidence to improve the prosecution of abusers.

Child fatality review teams are generally composed of representatives of the coroner or medical examiner's office, law enforcement agencies, prosecuting attorneys (from municipal, district, or state courts), child protective services agencies, and pediatricians and other health care professionals with expertise about child abuse. Some teams include representatives of mental health agencies, fire department or emergency personnel, probation and parole supervisors, educators and child care professionals, state or local child advocates, and sudden infant death syndrome experts (Granik et al., 1992). In some states, child fatality

review teams review every child death; in others, they examine only suspicious deaths.

Investigation of child deaths requires special training in pediatric forensics, pathology, child abuse, and forensic investigation. Researchers have concluded that the specialized review team is more likely to identify the indicators of child abuse and neglect than coroners or physicians who do not have special training (Lundstrom and Sharpe, 1991).

The model of fatality review teams is now being adopted by some cities and states (such as Florida) to investigate domestic violence fatalities as well, but this experience has not yet been described in the research literature.

Child Advocacy Centers

Community child advocacy centers have emerged to coordinate services to child victims of nonfatal abuse and neglect, especially in the area of child sexual abuse. The national Network of Children's Advocacy Centers estimates that there are 243 operational centers in 47 states in the United States.

An important goal of child advocacy centers is to reduce the redundancy, anxiety, and inconvenience that the child and family may experience as a result of family violence (especially sexual abuse). They seek to improve the handling of a maltreatment case during the stages of investigation, prosecution, and treatment by coordinating social services, health care, and law enforcement efforts. Typically, a child advocacy center is located in a facility that houses representatives of the jurisdiction's law enforcement, child protective services, prosecutors, child advocate, and mental health professionals. This model seeks to enhance interagency efficiency and effectiveness through the physical proximity of the center's multiagency staff, the designation of a child advocate who monitors the case through the various agency systems, and opportunity for formal and informal communication on a regular basis.

Coordinated Community Responses to Domestic Violence

A variety of approaches have been developed to create safe environments for women who have experienced domestic violence: community partnering, community intervention, task forces or coordinating councils, training and technical assistance projects, and community organizing. Designated as "coordinated community responses," these interventions are examples of multiple forms of service integration (Hart, 1995).

Community partnering relies on grass roots organizations to develop various initiatives identified in a strategic plan for community action. Community-wide intervention programs represent a broader scope of effort and provide direct services to batterers as well as victims. The intervention projects generally focus on the criminal justice system to achieve greater accountability in the response to

battered women and the deterrence of batterers. A well-known example of community-wide intervention is the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project in Duluth, Minnesota.

Task forces or coordinating councils are designed to coordinate and improve practices among key political leaders, public safety and emergency personnel, law enforcement officers, health care professionals, social service providers, and victim advocates to end violence against women. Task forces, often comprised of representatives of state and local government agencies and nonprofit organizations, may promulgate protocols or guidelines for practice, support training and technical assistance programs, identify areas in need of systemic reform, establish informal systems of communication, and facilitate conflict resolution and policy formation among diverse groups. In Seattle, for example, the Domestic Violence Coordinating Council includes several committees whose goal is to create and implement a five-year strategic plan to prevent domestic violence in the city.

Family Support Resource Centers

In its 1995 annual report, the U.S. Advisory Board on Child Abuse and Neglect urged the development of a "comprehensive, child-centered, family focused, and neighborhood-based system of services" to help prevent child maltreatment and reduce its negative consequences among those who have already been victimized. Such a system would include informal family and neighborhood support, assistance with difficult parenting issues via community-based programs, and crisis intervention services. Many of these services are discussed in Chapter 4—the advisory board's emphasis is on blending them and providing them in a local residential setting. The advisory board recommended that such a system should be the principal component of a primary prevention strategy aimed at families with infants and toddlers to reduce fatalities from abuse and neglect, to increase child safety, and to improve the functioning of all families.

A proliferation of efforts designed to establish social support for families at risk for child abuse or neglect has been described in the research literature (see, for example, the discussion of parenting practices and family support interventions in section 4A-1, also Garbarino and Kostelny, 1994). Family support resource centers differ from traditional social service interventions focused on parenting because they are proactive and are available on a universal basis to all families in the community rather than embedded in a treatment program provided only to families who have been reported for child abuse or neglect. Examples of such programs are family support, such as the Family Focus program (Weissbourd and Kagan, 1994); social support networks, such as Homemakers (Belle, 1989); parent education projects, such as the New Parents as Teachers Program (Pfannenstiel and Seltzer, 1989); and home health visitor programs, such as the

Elmira project described in Chapter 6 (Olds et al., 1986; Olds and Henderson, 1990).

Family support resource centers seek to establish and strengthen social support systems that can link social nurturance and social control during formative periods of child and family development (Garbarino, 1987; Weiss and Halpern, 1991). This strategy is designed to enhance community resources that can alter parenting styles acquired and reinforced through a lifetime of experience in a sometimes dysfunctional familial and social world (Garbarino and Kostelny, 1994). Two questions pervade analyses of family support programs: Can family support be a short-term "treatment" strategy, or must it be a condition of life? Can family support succeed amid conditions of chronic poverty or very high risk? These questions pose limiting factors that may influence the effects of neighborhood support programs, including those focused on child maltreatment (Garbarino and Kostelny, 1994).

For parents who lack basic educational skills and experience with positive disciplinary practices, family support resource centers and parent support groups may help reduce the risks of maltreatment associated with corporal punishment and impulsive behaviors. However, these interventions may be ill-equipped to protect children in families with such problems as substance abuse, long-term health or mental health disorders, inadequate housing or homelessness, chronic unemployment, or other dysfunction that threatens the basic stability and integrity of family life. The length and intensity of effort necessary to support good parenting practices in these types of social settings may require extensive resources that can address the developmental stages of children and families and respond to shifting needs over time.

Substance Abuse and Domestic Violence Treatment

It is beyond the scope of this report to review all community interventions that attempt to reduce family violence by addressing environmental and situational risk factors, such as poverty, unemployment, substance abuse, teenage and single parenting, and social isolation. We did, however, examine community intervention programs that seek to create opportunities for behavioral change in multiple dimensions, for example altering the link between substance abuse and violence against women.

Some communities have taken steps to integrate components of substance abuse treatment into domestic violence prevention programs and vice versa. These efforts take a variety of forms, including joint training on the two problems—an integrated approach—and the addition of a separate curriculum or speaker on a related topic—an additive approach. The relative effects of integrated and additive programs, compared with each other and with more traditional single-topic prevention programs, have not been evaluated.

One study of agency services in Illinois, indicated that, although service

providers from both substance abuse and domestic violence programs wanted to collaborate with each other, their conceptual frameworks about causal factors and theories of change contained fundamental differences (Bennett and Lawson, 1994:286):

Battered-women's advocates, in general, believe that abuse is a deliberate and volitional act. The batterer must accept full responsibility for his violence and must learn both self-control and respect for women. Addictions counselors generally believe that a disease process, beyond the control of the addict, causes dysfunctional behaviors.

These differences in beliefs may militate against service integration and comprehensive service initiatives. One study suggested as much by observing that data on the referral experience in substance abuse/domestic violence cross-problem interventions indicates a pattern of weak linkage and low referral rates (Bennett and Lawson, 1994). For example, 23 percent of the substance abuse staff surveyed stated that they never referred their clients to domestic violence programs. The authors concluded that service provider differences in beliefs about the role of self-control in substance abuse and domestic violence was the most significant factor that impeded collaboration.

Community Interventions for Injury Control and Violence Prevention

Community interventions to address injury control and violence prevention are based on two assumptions: that multiple interventions aimed at one or more forms of injury will be more effective in reducing risk factors than a single intervention, and that an injury or violence prevention campaign that is oriented to the community will be more successful than one that is oriented to individuals. The community approach often involves public education campaigns in a particular community, highlighting the need for and ways to prevent all forms of injury or violence. More recently, public health efforts have been used to influence behavioral changes in the community with respect to risk factors and health outcomes, especially in preventing cardiovascular disease and smoking.

Youth violence prevention is one area of community interventions designed to integrate public health approaches with local crime control. A recent review of 15 evaluation studies of youth violence prevention programs identified several evaluation issues that require attention (Powell and Hawkins, 1996): the presence of multiple collaborating organizations; scientific and programmatic tension; the enrollment of control groups; subject mobility; the paucity of established and practical measurement instruments; complex relationships between interventions and outcomes; analytic complexities; unexpected and disruptive events; replicability; and the relative ease of research on individuals as opposed to groups. Many of these issues characterize evaluation research on other types

of family violence interventions, suggesting the need for opportunities to exchange knowledge and expertise between these fields.

In 1992 and 1993, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched a series of evaluations of 15 youth violence prevention projects in 12 U.S. cities and one county. Although these projects include different types of violence prevention strategies, they are all based on theoretical models that draw on scientific research (for a review see Powell and Hawkins, 1996). The strategies used to implement community-based youth violence prevention programs also may be valuable in planning family violence interventions because the youth violence programs often consist of multiple interventions implemented as a unit for a highly diverse population.

Battered Women's Shelters

As mentioned in Chapter 4, the emergence in the 1980s of shelters for battered women as a major intervention focused on community change had its roots in the feminist and anti-rape movements of the 1970s (Schechter, 1982). These movements exposed ways in which existing health, legal, and social service systems were not responsive to the needs of women and stimulated institutional reforms to create alternative approaches to providing emotional and legal support in confronting male violence. Reforms were often stimulated by knowledge gained both from professionals involved in rape crisis centers and by the experiences and insights of rape crisis service providers, who were often suspicious of those who sought to blame women for male violence (Schechter, 1982).

Shelter providers often worked to connect individual victims and their supporters with political and economic resources that could break down the institutional and psychological barriers that isolated the experience of rape victims and battered women. Battered women's shelters thus became a catalyst for community service reforms as well as a direct service provider. This role fostered reforms that expanded professional service resources for battered women in a variety of institutional settings, including hospitals, emergency shelters, and women's health programs. Evaluations of the role and impact of battered women's shelters have often missed these effects because of their emphasis on direct service outcomes.

Community Partnerships for Substance Abuse Prevention

In the early 1990s, the federal government initiated the Community Partnership Demonstration Program. Described as a "macro-strategy" by Cook et al. (1994), this intervention is designed to prevent abuse of alcohol, tobacco, and other drug addiction through the creation of collaborative and coordinated efforts among multiple key organizations and groups serving more than 250 individual local communities across the nation (Kaftarian and Hansen, 1994). Participant

agencies include health, social service, criminal justice, and education agencies as well as voluntary and community organizations, private businesses, elected officials, the religious community, and grass roots groups.

The evaluation strategies and research experiences tied to these interventions may be able to guide improved evaluations of community-change interventions in the field of family violence. At this time, however, little is known about unique community factors or organizational arrangements that may facilitate or discourage the adaptation of this approach to family violence (Kaftarian and Hansen, 1994; Lorion et al., 1994; Hunt, 1994). Those who have studied service integration, comprehensive services, and community-change programs have emphasized the need for attention on the implementation process and the innovative efforts and resources needed to design and sustain these types of interventions. They also voice caution about integrating lessons drawn from diverse local community and program settings into a core program philosophy and guiding principles to reshape local projects. These studies demonstrate the difficulty of establishing long-term research programs within a culture of interventions that are focused strongly on empowering communities, short-term action, integrated and comprehensive services, and sustaining financial resources and organizational viability.

Improving Evaluation

Chapter 3 contains the committee's major discussion of evaluation of community-based initiatives. Despite the paucity of evidence of the effectiveness of community interventions focused on family violence, evaluation studies in other fields are generating analytical frameworks, measurement tools, and data collection efforts that offer valuable insights. Community-based research is being pursued on children and families (Connell et al., 1995; Connell and Kubisch, 1996; Kahn and Kamerman, 1996), substance abuse prevention (Kaftarian and Hansen, 1994), and child maltreatment (Garbarino and Kostelny, 1994).

In the field of public health, several well-designed large-scale trials have been conducted in the last 15 years to test the impact of particular public health community intervention programs.1 Yet few of these interventions have had significant impact in terms of widespread behavioral change; rigorous evaluations of most have shown meager effect sizes in relation to the effort expended (Susser, 1995). Four decades of experience with public health interventions in smoking prevention indicates that social movements directed toward behavioral change require extensive time to be effective. The experience with community

trials in changing smoking behavior also suggests that it is very difficult to detect change produced by interventions when large-scale programs are implemented after a social movement is under way. Small effect sizes for the interventions may simply show that the degree of change attainable by the program has already been reached by the progress of the social movement (Susser, 1995).

The experience with community trials also suggests that additional knowledge is required to improve their effectiveness with special target populations, such as youth or individuals who may be chemically addicted or chronically exposed to certain types of behavior and are thus more resistant to change than the general population.

A number of key questions must be explored in the evaluation of community change interventions:

- Does the presence or absence of community interventions alter the motivation and behavior of at-risk individuals, particularly in terms of their willingness to participate or become involved in formal and informal groups or to use these groups to gain access to services in traditional agency settings?

- Do changes in patterns of group participation or the creation of social and political networks in the community result in greater availability or use of agency services and support systems?

- Does the presence or use of community services and support systems change child, family, or community outcomes? In what dimensions?

- What levels of intensity and what time periods are needed in deprived communities to achieve significant changes in regional rates of family violence, especially among groups that experience multiple problems?

- What are the most critical areas and what is the rate of change in child, family, and community outcomes that are associated with service integration, comprehensive service, and community-change interventions? Do these areas or rates accelerate or decline in the presence or absence of specific agencies or political leaders? How are they affected by the creation of new organizational structures, the extent of local community participation, or changing social norms?

Conclusions

Although comprehensive community interventions are an area of growing interest and activity in the field of family violence, they represent one of the most difficult areas for evaluation research, and their impact remains unexamined in the research literature. Unique methodological challenges confront the development of studies of these interventions, and creative strategies are required to foster partnerships among researchers, service providers, and community residents to assess the strengths and limitations of these efforts to address family violence.

No single model of service integration, comprehensive services, or community

change can be endorsed at this time; however, a range of interesting designs has emerged that have widespread popularity and support in local communities. Because their primary focus is often on prevention rather than treatment, comprehensive community interventions have the potential to reduce the scope and severity of family violence as well as contribute to remedies to other important social problems.

Despite their methodological challenges, these initiatives merit systematic evaluation that could focus on several key factors:

- What resource requirements and processes are necessary to implement comprehensive community interventions focused on family violence treatment and prevention? What critical components contribute to their effectiveness in different social, political, and economic climates?

- Do comprehensive community interventions have greater impact on reducing risk factors, enhancing protective factors, or both? Do adequate measures exist to examine the critical domains in which changes are expected to occur (such as the quality of social support for children, adults, and families or the timing of services) as a result of a community intervention?

- Is the impact of comprehensive community interventions stronger or weaker when their focus is restricted to a particular population, problem, or behavior? Are the strategies that are developed in one area (such as domestic violence) useful in addressing other forms of family violence or the relationships between family and community violence?

- How can the evaluations of comprehensive community interventions for family violence draw lessons from evaluation experiences in other areas of prevention research, especially with regard to study design, sample recruitment and retention, and measurement?