3

Improving Evaluation

Improving the standards of evidence used in the evaluation of family violence interventions is one of the most critical needs in this field. Given the complexity and unique history of family violence interventions, researchers and service providers have used a variety of methods and a broad array of measures and evaluation strategies over the past two decades. This experimentation has contributed important ideas (using qualitative and quantitative methods) that have helped to establish a baseline for the assessment of individual programs. What is lacking, however, is a capacity and research base that can offer specific guidance to key decision makers and the broader service provider community about the impact or relative effectiveness of specific interventions, as well as broad service strategies, to address the multiple dimensions of family violence.

Recognizing that more rigorous studies are needed to better determine ''what works," "for whom," "under what conditions," and "at what cost," the committee sought to identify research strategies and components of evaluation designs that represent key opportunities for improvement. The road to improvement requires attention to four areas: (1) assessing the limitations of current evaluations, (2) forging functional partnerships between researchers and service providers, (3) addressing the dynamics of collaboration in those partnerships, and (4) exploring new evaluation methods to assess comprehensive community initiatives.

The emerging emphasis on integrated, multifaceted, community-based approaches to treatment and prevention services, in particular, presents a new dilemma in evaluating family violence interventions: comprehensive interventions are particularly difficult, if not impossible, to implement as well as study using experimental or quasi-experimental designs. Efforts to resolve this dilemma may

benefit from attention to service design, program implementation, and assessment experiences in related fields (such as substance abuse and teenage pregnancy prevention). These experiences could reveal innovative methods, common lessons, and reliable measures in the design and development of comprehensive community interventions, especially in areas characterized by individualized services, principles of self-determination, and community-wide participation.

Improving on study design and methodology is important, since technical improvements are necessary to strengthen the science base. But the dynamics of the relationships between researchers and service providers are also important; a creative and mutually beneficial partnership can enhance both research and program design.

Two additional points warrant mention in a broad discussion of the status of evaluations of family violence interventions. First, learning more about the effectiveness of programs, interventions, and service strategies requires the development of controlled studies and reliable measures, preceded by detailed process evaluations and case studies that can delve into the nature and clients of a particular intervention as well as aspects of the institutional or community settings that facilitate or impede implementation. Second, the range of interactions between treatment and clients requires closer attention to variations in the individual histories and social settings of the clients involved. These interactions can be studied in longitudinal studies or evaluations that pair clients and treatment regimens and allow researchers to follow cohorts over time within the general study group.

Assessing The Limitations Of Current Evaluations

The limitations of the empirical evidence for family violence interventions are not new, nor are they unique. For violence interventions of all kinds, few examples provide sufficient evidence to recommend the implementation of a particular program (National Research Council, 1993b). And numerous reviews indicate that evaluation studies of many social policies achieve low rates of technical quality (Cordray, 1993; Lipsey et al., 1985). A recent National Research Council study offered two explanations for the poor quality of evaluations of violence interventions: (1) most evaluations were not planned as part of the introduction of a program and (2) evaluation designs were too weak to reach a conclusion as to the program's effects (National Research Council, 1993b).

The field cannot be improved simply by urging researchers and service providers to strengthen the standards of evidence used in evaluation studies. Nor can it be improved simply by urging that evaluation studies be introduced in the early stages of the planning and design of interventions. Specific attention is needed to the hierarchy of study designs, the developmental stages of evaluation research and interventions, the marginal role of research in service settings, and

the difficulties associated with imposing experimental conditions in service settings.

A Hierarchy of Study Designs

The evaluation of family violence interventions requires research directed at estimating the unique effects (or net impact) of the intervention, above and beyond any change that may have occurred because of a multitude of other factors. Such research requires study designs that can distinguish the impact of the intervention within a general service population from other changes that occur only in certain groups or that result simply as a passage of time. These design commonly involve the formation of (at least) two groups: one composed of individuals who participated in the intervention (often called the treatment or experimental group) and a second group composed of individuals who are comparable in character and experience to those who participated in the intervention but who received no services or received an intervention that was significantly different from that under study (the control or comparison group). Some study designs involve multiple treatment groups who receive modified forms of the services that are the subject of the evaluation; other studies use one subject group, but sample the group at multiple times prior to and after the intervention to determine whether the measures immediately before and after the program are a continuation of earlier patterns or whether they indicate a decisive change that endures after the cessation of services; this is called a time-series design (Campbell and Stanley, 1966, and Weiss, 1972, are two comprehensive primers on the basic principles and designs of program assessment and evaluation research).

Study designs that rely on a comparison group, or that use a time-series design, are commonly viewed as more reliable than evaluation studies that simply test a single treatment group prior to and after an intervention (often called a pre-post study). More rigorous experimental designs, which involve the use of a randomized control group, are able to distinguish changes in behavior or attitude that occur as a result of the intervention from those that are influenced by maturation (the tendency for many individuals to improve over time), self-selection (the tendency of individuals who are motivated to change to seek out and continue their involvement with an intervention that is helping them), and other sources of bias that may influence the outcome of the intervention.

The importance of estimating the net impact of innovative services and determining their comparative value highlights several technical issues:

- The manner in which the control or comparison groups are formulated influences the validity of the inference that can be drawn regarding net effects.

- The number of participants enrolled in each group (the sample size) must be sufficient to permit statistical detection of differences between the groups, if one exists.

- There should be agreement among interested parties that a selected outcome is important to measure, that it is a valid reflection of the objective of the intervention, and that it can reflect change over time.

- Evidence is needed that the innovative services were actually provided as planned, and that the differences between the innovative services and usual services were large enough to generate meaningful differences in the outcome of interest.

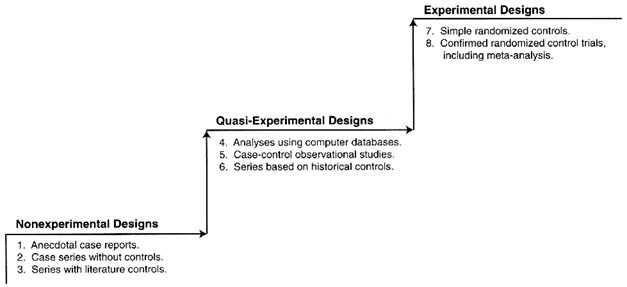

Over the last few decades, evaluation research has developed a general consensus about the relative strength of various study designs used to assess the effectiveness (or net effects) of interventions (Figure 3-1; see also Green and Byar, 1984). The lowest level of evidence in the hierarchy is nonexperimental designs, which include case studies and anecdotal reports. This type of research often consists of detailed histories of participant experiences with an intervention. Although they may contain a wealth of information, nonexperimental studies cannot provide a strong base for inference because they are unable to control for such factors as maturation, self-selection, the interaction of selection and maturation (the tendency for those with more or less severe problem levels to mature at differential rates), historical influences that are unrelated to the intervention, other interventions they may have received, a variety of response biases and demand characteristics, and changes in instrumentation (the interviewer becomes more familiar with the client over the course of the study).

The next level of evidence is quasi-experimental research designs (levels 4 through 6 in Figure 3-1). Although these designs can improve inferential clarity, they cannot be relied on to yield unbiased estimates of the effects of interventions because the research subjects are not assigned randomly. Two research reviews of family violence interventions suggest that some trustworthy information can be extracted from quasi-experimental designs, so they are not without merit (Finkelhor and Berliner, 1995; Heneghan et al., 1996). Although quasi-experimental study designs can provide evidence that a relationship exists between participation in the intervention and the outcome, the magnitude of the net effect is difficult to determine. In other fields, quasi-experimental results are more trustworthy when the studies involve a broader evidential basis than simple prepost designs (Cook and Campbell, 1979; Cordray, 1986).

The highest level of evidence is experimental designs that include controls to restrict a number of important threats to internal validity. These are the least prevalent types of designs in the family violence literature. Although, in theory, properly designed and executed experiments can produce unbiased estimates of net effects, other threats to validity emerge when they are conducted in largely uncontrolled settings. Such threats involve various forms of generalization (across persons, settings, time, and other constructs of interest), statistical problems, and logistical problems (e.g., differential attrition from measurement or noncompliance with the intervention protocol). These other threats to validity

can be addressed by replications and the synthesis of research results, including the use of meta-analysis (Lipsey and Wilson, 1993). Replication is an essential part of the scientific process; replication studies can reveal evidence from both successes and failures. The proper use of research synthesis can provide a tool for understanding variation and similarities across studies and will uncover robust intervention effects, if they are present, even if the individual studies are not generalizable because their samples are not representative, the interventions are unique, or their measures are inconsistent (Cook and Shadish, 1994; Cordray, 1993; Colditz et al., 1995).

Developmental Stages of Research

Interventions often undergo an evolutionary process that refines theories, services, and approaches over time. In the early stages, interventions generate reform efforts and evaluations that rely primarily on descriptive studies and anecdotal data. As these interventions and evaluation efforts mature, they begin to approach the standards of evidence needed to make confident judgments about effectiveness and cost.

Current discussions about what is known about family violence interventions are often focused on determining the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of selected programs, interventions, or strategies. Conclusions about effectiveness require fairly high standards of evidence because an evaluation must demonstrate, with high certainty, that the intervention of interest is responsible for the observed effects. This high standard of evidence is warranted to change major policies, but it may inhibit a careful assessment of what can be derived from a knowledge base that is still immature.

Of the more than 2,000 evaluation studies identified by the committee in the course of this study, the large majority consist of nonexperimental study designs. For example, one review of 29 studies of the treatment of sexually abused children indicated that more than half of the studies (17) were pre-post (also called before and after) designs that evaluated the same group of children at two or more time intervals during which some kind of professional intervention was provided (Finkelhor and Berliner, 1995). Similarly, a methodological review of intensive family preservation services programs excluded 36 of 46 identified program evaluations because they contained no comparison groups (Heneghan et al., 1996). Thus, while hundreds of evaluation studies exist in the family violence research literature, most of them provide no firm basis for examining the relative impact of a specific intervention or considering the ways in which different types of clients respond to a treatment, prevention, or deterrence intervention.

Still, nonexperimental studies can reveal important information in the developmental process of research. They can illuminate the characteristics and experience of program participants, the nature of the presenting problems, and issues associated with efforts to implement individual programs or to change systems of

service within the community. Although these kinds of studies cannot provide evidence of effectiveness, they do represent important building blocks in evaluation research.

Developmental Stages of Interventions

A similar developmental process exists on the programmatic side of interventions. Many family violence treatment and prevention programs have their origins in the efforts of advocates concerned about children, women, elderly people, and the family unit. Over several decades of organized activity, these efforts have fostered the development of interventions in social service, health, and law enforcement settings that program sponsors believe will improve the welfare of victims or control and reduce the violent behavior of perpetrators. Some programs are based on common sense and legal authority, such as mandatory reporting requirements; some are based on theories borrowed from other areas, such as counseling services for victims of trauma (Azar, 1988); and some are based on broad theories of human interaction that are difficult to operationalize, such as comprehensive community interventions. Rarely do family violence interventions result from the development of theory or data collection efforts that precede the implementation of a particular program or strategy. Significant exceptions can be found in some areas, however, such as the treatment of domestic violence (especially the use of arrest policies) and the development of home visitation services and intensive family preservation services. All these interventions were preceded by research studies that identified critical decision points in the intervention process that could be influenced by policy or service reforms (such as deterrence research in domestic violence cases) and research suggesting that families may be more responsive to services during times of crisis (such as a decision to move a child from a family setting into out-of-home placement) or change (such as the birth of a child).

Initial attempts to implement strategies are followed by refinements that include concrete descriptions of services, the development of models to differentiate types of interventions, and the emergence of theories or rationales to explain why particular approaches ought to be effective. As these models are replicated, empirical evidence and experience emerge that clarify who is best served by a particular intervention and under what circumstances. As programs mature and become better articulated and implemented, the evaluation questions and methods become more complex.

The Marginal Role of Research in Service Settings

Most research on family violence interventions is concentrated in social service settings, in which researchers have comparatively easy access to clients and can exert greater control over the service implementation process that accompanied

the development of the intervention. Research is also concentrated in the area of child maltreatment, which has a longer history of interventions than domestic violence or elder abuse. It is important to reiterate that the distribution of the evaluation studies reviewed in this report does not match the history of the programs and the interventions themselves. Some interventions, such as home visitation and family preservation services, are comparatively new and employ innovative service strategies. Because they easily lend themselves to evaluation of small study populations, they have been the subject of numerous evaluation studies. Other, more extensive interventions, such as foster care, judicial rulings on child placement, and shelter services for battered women, involve larger numbers of individuals and are more resistant to study because they are deeply embedded in major institutional or advocacy settings that are often not receptive to or do not have the resources to support research. As a result, research is often marginalized in discussions of the effectiveness of certain programs or service strategies, and the conditions that can foster empirical program evaluation studies are restricted to a fairly narrow range of program activity.

This situation appears to be changing. The growing costs of ongoing interventions have stimulated interest in the public sector in knowing more about the processes, effects, and outcomes associated with service strategies, interventions, and programs. In the site visits and workshops that were part of our study, program advocates with extensive experience with different service models expressed a receptivity to learning more about specific components of service systems that can allow them to tailor services to the individual needs of their clients and communities. Researchers have documented the variation among victims and offenders, suggesting that, in assigning cases to service categories, repetitive and chronic cases should be distinguished from those that are episodic or stimulated by unusual stress. Furthermore, inconsistent findings and uncertainties associated with the ways in which clients are referred to or selected for programs and interventions suggest that more attention should be focused on the pathways by which individual victims or offenders enter different service settings.

There is now greater interest in understanding the social, economic, legal, and political processes that shape the development of family violence interventions. At the same time, program advocates have begun to focus on the development of comprehensive community interventions that can move beyond the difficulties associated with providing professional services in institutional settings and establish resource centers that can aid parents, families, women, and children in their own communities. The development of these comprehensive and individualized interventions has stimulated further interest in knowing more about the ways in which client characteristics, service settings, and program content interact to stimulate behavioral change and lead to a reduction in child maltreatment, domestic violence, and elder abuse.

Imposing Experimental Conditions in Service Settings

It is difficult for researchers to establish good standards of evidence when they cannot exert complete control over the selection of clients and the implementation of the intervention. But several strategies have emerged in other fields that can guide the development of evaluation research as it moves from its descriptive stage into the conduct of quasi-experimental and true experimental studies.

An important part of this process is the development of a "fleet of studies" (Cronbach and Snow, 1981) that can provide a broad and rich understanding of a specific intervention. For example, a recent report by the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine used a variety of sources of evaluation information to examine the effects of needle exchange programs on the risk of HIV transmission for intravenous drug users (National Research Council, 1995). Several program evaluations conducted over several years made it possible for the study panel to examine the pattern of evidence about the effectiveness of the needle exchange program. Although each individual study of a given project was insufficient to support a claim that the needle exchange program was effective, the collective strengths of this fleet of studies taken together provided a basis for a firm inference about effectiveness.

The only fleet of studies identified in our review of evaluations is the Spousal Arrest Replication Program (SARP) discussed in Chapter 5 . In contrast, although multiple studies have been conducted of parenting programs and family support interventions (such as lay counseling, peer group support, and parent education), their dimensions, subject samples, and instrumentation are too varied to allow strong inferences to be developed at this time.

Evaluation may lag behind the development and refinement of intervention programs, especially when there is a rush to experiment without establishing the necessary conditions for a successful endeavor. Premature experimentation can leave the impression that nothing works, especially if the problem to be addressed is complex, interventions are limited, and program effects are obscure. Yet early program experimentation studies can be helpful in describing the characteristics of clients who appear to be receptive or impervious to change, documenting the barriers to program implementation, and estimating the size, intensity, costs, and duration of the intervention that may be required. If these lessons can be captured, they are a valuable resource in moving the research and program base to a new level of development, one that can address multiple and contextual interactions.

Flaws in Current Evaluations

The committee identified 114 evaluation studies conducted in the period 1980-1996 that have sufficient scientific strength to provide insights on the effects

of specific interventions in the area of child maltreatment, domestic violence, and elder abuse (Table 3-1). This time period was selected because it provides a contemporary history of the evaluation research literature while maintaining manageable limits on the scope of the evidence considered by the committee. As noted in Chapter 1, each of the studies employed an experimental or quasi-experimental research design, used reliable research instrumentation, and included a control or comparison group. In addition, a set of 35 detailed review articles summarizes a broader set of studies that rely on less rigorous standards but offer important insights into the nature and consequences of specific interventions (Table 3-2). Most of the 114 studies identified by the committee focus on interventions conducted in the United States. As a group, these studies represent only a small portion of the enormous array of evaluation research that has been conducted.

A rigorous assessment of the quasi-experimental studies and research review papers reveals many methodological weaknesses, including differences in the nature of the treatment and control groups, sample sizes that are too small to detect medium or small effects of the intervention, research measures that are unreliable or that yield divergent results with different ethnic and cultural groups, short periods of follow-up, and lack of specificity and consistency in program content and services. The lack of equivalence between treatment and control groups in quasi-experimental studies can be illustrated in one study of therapeutic treatment of sexually abused children, in which children in the therapy group were compared with a group of no-therapy children (Sullivan et al., 1992). In a review of the study findings, the authors note that although children who received treatment had significantly fewer behavior problems at a one-year follow-up assessment, the no-therapy comparison group consisted of children whose parents had specifically refused therapy for their children when it was offered (Finkelhor and Berliner, 1995). This observation suggests that other systematic differences could exist within the two groups that affected their recovery (for example, having parents who were or were not supportive of psychological interventions).

Similarly, a review of intensive family preservation services programs indicated that, in a major Illinois evaluation of the intervention, the 2,000 families included were distributed across six sites that administered significantly different types of programs and services (Rossi, 1992). As a result, the sample size was reduced to the 333 families associated with each individual site; small effects associated with the intervention, if they occurred, could not be observed (Rossi, 1992). A later methodological review of intensive family preservation services indicated that 5 of 10 studies that used control or comparison groups had treatment groups that included fewer than 100 participants (Heneghan et al., 1996).

The quality of the existing research base of evaluations of family violence interventions is therefore insufficient to provide confident inferences to guide policy and practice, except in a few areas that we identify in this report. Nevertheless,

TABLE 3-1 Interventions by Type of Strategy and Relevant Quasi-Experimental Evaluations, 1980-1996

|

Intervention |

Quasi-Experimental Evaluations |

|

Parenting practices and family support services 4A-1 |

Barth et al., 1988 Barth, 1991 Brunk et al., 1987 Burch and Mohr, 1980 Egan, 1983 Gaudin et al., 1991 Hornick and Clarke, 1986 Lutzker et al., 1984 National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect, 1983a,b Reid et al., 1981 Resnick, 1985 Schinke et al., 1986 Wesch and Lutzker, 1991 Whiteman et al., 1987 |

|

School-based sexual abuse prevention 4A-2 |

Conte et al., 1985 Fryer et al., 1987 Harvey et al., 1988 Hazzard et al., 1991 Kleemeier et al., 1988 Kolko et al., 1989 McGrath et al., 1987 Miltenberger and Thiesse-Duffy, 1988 Peraino, 1990 Randolph and Gold, 1994 Saslawsky and Wurtele, 1986 Wolfe et al., 1986 Wurtele et al., 1986, 1991 |

|

Child protective services investigation and casework 4A-3 |

|

|

Intensive family preservation services 4A-4 |

AuClaire and Schwartz, 1986 Barton, 1994 Bergquist et al., 1993 Dennis-Small and Washburn, 1986 Feldman, 1991 Halper and Jones, 1981 Pecora et al., 1992 Schuerman et al., 1994 Schwartz et al., 1991 Szykula and Fleischman, 1985 Walton et al., 1993 Walton, 1994 Wood et al., 1988 Yuan et al., 1990 |

|

Intervention |

Quasi-Experimental Evaluations |

|

Child placement services 4A-5 |

Chamberlain et al., 1992 Elmer, 1986 Runyan and Gould, 1985 Wald et al., 1988 |

|

Individualized service programs 4A-6 |

Clark et al., 1994 Hotaling et al., undated Jones, 1985 |

|

Shelters for battered women 4B-1 |

Berk et al., 1986 |

|

Peer support groups for battered women 4B-2 |

|

|

Advocacy services for battered women 4B-3 |

Sullivan and Davidson, 1991 Tan et al., 1995 |

|

Domestic violence prevention programs 4B-4 |

Jaffe et al., 1992 Jones, 1991 Krajewski et al., 1996 Lavoie et al., 1995 |

|

Adult protective services 4C-1 |

|

|

Training for caregivers 4C-2 |

Scogin et al., 1989 |

|

Advocacy services to prevent elder abuse 4C-3 |

Filinson, 1993 |

|

Mandatory reporting requirements 5A-1 |

|

|

Child placement by the courts 5A-2 |

|

|

Court-mandated treatment for child abuse offenders 5A-3 |

Irueste-Montes and Montes, 1988 Wolfe et al., 1980 |

|

Treatment for sexual abuse offenders 5A-4 |

Lang et al., 1988 Marshall and Barbaree, 1988 |

|

Criminal prosecution of child abuse offenders 5A-5 |

|

|

Improving child witnessing 5A-6 |

|

|

Evidentiary reforms 5A-7 |

|

|

Intervention |

Quasi-Experimental Evaluations |

|

Procedural reforms 5A-8 |

|

|

Reporting requirements 5B-1 |

|

|

Protective orders 5B-2 |

|

|

Arrest procedures 5B-3 |

Berk et al., 1992a Dunford et al., 1990 Ford and Regoli, 1993 Hirschel and Hutchison, 1992 Pate and Hamilton, 1992 Sherman and Berk, 1984a,b Sherman et al., 1992a,b Steinman 1988, 1990 |

|

Court-mandated treatment for domestic violence offenders 5B-4 |

Chen et al., 1989 Dutton, 1986 Edleson and Grusznski, 1989 Edleson and Syers, 1990 Hamberger and Hastings, 1988 Harrell, 1992 Palmer et al., 1992 Tolman and Bhosley, 1989 |

|

Criminal prosecution 5B-5 |

Ford and Regoli, 1993 |

|

Specialized courts 5B-6 |

|

|

Systemic approaches 5B-7 |

Davis and Taylor, 1995 Gamache et al., 1988 |

|

Training for criminal justice personnel 5B-8 |

|

|

Reporting requirements 5C-1 |

|

|

Protective orders 5C-2 |

|

|

Education and legal counseling 5C-3 |

|

|

Guardians and conservators 5C-4 |

|

|

Arrest, prosecution, and other litigation 5C-5 |

|

|

Identification and screening 6A-1 |

Brayden et al., 1993 |

|

Intervention |

Quasi-Experimental Evaluations |

|

Mental health services for child victims of physical abuse and neglect 6A-2 |

Culp et al., 1991 Fantuzzo et al., 1987 Fantuzzo et al., 1988 Kolko, 1996a,b |

|

Mental health services for child victims of sexual abuse 6A-3 |

Berliner and Saunders, 1996 Cohen and Mannarino, 1996 Deblinger et al., 1996 Downing et al., 1988 Oates et al., 1994 Verleur et al., 1986 Wollert, 1988 |

|

Mental health services for children who witness domestic violence 6A-4 |

Jaffe et al., 1986b Wagar and Rodway, 1995 |

|

Mental health services for adult survivors of child abuse 6A-5 |

Alexander et al., 1989, 1991 |

|

Home visitation and family support programs 6A-6 |

Larson, 1980 Marcenko and Spence, 1994 National Committee to Prevent Child Abuse, 1996 Olds, 1992 Olds et al., 1986, 1988, 1994, 1995 Scarr and McCartney, 1988 |

|

Domestic violence screening, identification, and medical care responses 6B-1 |

McLeer et al., 1989 McLeer and Anwar, 1989 Olson et al., 1996 Tilden and Shepherd, 1987 |

|

Mental health services for domestic violence victims 6B-2 |

Bergman and Brismar, 1991 Cox and Stoltenberg, 1991 Harris et al., 1988 O'Leary et al., 1994 |

|

Elder abuse identification and screening 6C-1 |

|

|

Hospital multidisciplinary teams 6C-2 |

|

|

Hospital-based support groups 6C-3 |

|

|

SOURCE: Committee on the Assessment of Family Violence Interventions, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 1998. |

|

TABLE 3-2 Reviews of Multiple Studies and Evaluations

|

Type of Abuse |

Citation |

Focus |

Studies Reviewed |

|

1. Child abuse |

Becker and Hunter, 1992 |

A review of interventions with adult child molesters, intrafamilial and extrafamilial. |

27 studies |

|

2. Child abuse |

Blythe, 1983 |

A review of interventions with abusive families. |

16 studies |

|

3. Child abuse |

Briere, 1996 |

A review of treatment outcome studies for abused children. |

3 studies |

|

4. Child abuse |

Carroll et al., 1992 |

An evaluation of school curricula child sexual abuse prevention program evaluations. |

18 programs |

|

5. Child abuse |

Cohen et al., 1984 |

A review of evaluations (many completed prior to 1980) of programs to prevent child maltreatment: early and extended contact, perinatal support programs, parent education classes, and counseling programs. |

20 studies |

|

6. Child abuse |

Cohn and Daro, 1987 |

Review of child neglect and abuse prevention programs. |

4 evaluations |

|

7. Child abuse |

Dubowitz, 1990 |

Review of evaluations of cost and effectiveness of child abuse interventions. |

5 evaluations |

|

8. Child abuse |

Fantuzzo and Twentyman, 1986 |

A review of psychotherapeutic interventions with victims of child abuse. |

30 studies |

|

9. Child abuse |

Fink and McCloskey, 1990 |

Review of child abuse prevention programs. |

13 evaluations |

|

10. Child abuse |

Finkelhor and Berliner, 1995 |

Review of child abuse treatment programs, characterizing them by type of study design. Included sex education, music therapy, family therapy, group therapy, and cognitive behavioral treatment. |

29 evaluations |

|

11. Child abuse |

Frankel, 1988 |

Review of family-centered, home-based services for child protection. |

7 studies |

|

12. Child abuse |

Fraser et al., 1991 |

Review of family and home-based services and intensive family preservation programs. |

7 studies |

|

Type of Abuse |

Citation |

Focus |

Studies Reviewed |

|

13. Child abuse |

Garbarino, 1986 |

Review of results of child abuse prevention programs. |

5 studies |

|

14. Child abuse |

Heneghan et al., 1996 |

A review of 46 family preservation services program evaluations, including 5 randomized trials and 5 quasi-experimental studies. |

10 studies |

|

15. Child abuse |

Kelly, 1982 |

A review of integral components of behavioral treatment strategies to reorient pedophiliacs. |

32 studies |

|

16. Child abuse |

Kolko, 1988 |

A review of in-school programs to prevent child sexual abuse. |

15 studies |

|

17. Child abuse |

McCurdy, 1995 |

A review of evaluations of home visiting programs. |

10 studies |

|

18. Child abuse |

McDonald et al., 1990 |

Comparison review of California Homebuilder-type interventions including in-home services designed to improve parenting skills and access to community resources. |

8 in-home care projects |

|

19. Child abuse |

McDonald et al., 1993 |

Comparison of the findings of evaluations of foster care programs. |

27 studies |

|

20. Child abuse |

National Resource Center on Family Based Services, 1986 |

An evaluation of child placement prevention projects in Wisconsin from 1983-1985. |

14 projects |

|

21. Child abuse |

O'Donohue and Elliott, 1992 |

A review of evaluations of psychotherapeutic interventions for sexually abused children. |

11 studies |

|

22. Child abuse |

Olds and Kitzman, 1990 |

Review of randomized trials of prenatal and infancy home visitation programs for socially disadvantaged women and children. |

26 studies |

|

23. Child abuse |

Olds and Kitzman, 1993 |

Review of randomized trials of home visitation programs designed to ameliorate child outcomes including maltreatment. |

19 studies |

|

Type of Abuse |

Citation |

Focus |

Studies Reviewed |

|

24. Child abuse |

Pecora et al., 1992 |

Review of studies of family-based and intensive family preservation programs. |

12 studies |

|

25. Child abuse |

Rossi, 1992 |

Review of Homebuilders-type programs. |

9 studies |

|

26. Child abuse |

Sturkie, 1983 |

Review of group treatment interventions for victims of child sexual abuse. |

18 studies |

|

27. Child abuse |

Wolfe and Wekerle, 1993 |

Review of studies reporting on treatment outcomes with abusive and/or neglectful parents and children. |

21 studies |

|

28. Child abuse |

Wurtele, 1987 |

Review of results of school curricula to teach children sexual abuse prevention skills. |

11 studies |

|

29. Domestic violence |

Edleson and Tolman, 1992 |

Review of group batterer treatment programs for male spouse abusers. |

10 studies |

|

30. Domestic violence |

Eisikovits and Edleson, 1989 |

Review of outcome studies of batterer treatment programs. |

approximately 20 studies |

|

31. Domestic violence |

Gondolf, 1991 |

Review of results of evaluations of court-mandated and voluntary batterer counseling programs. |

30 batterer programs studied, 6 evaluations reviewed |

|

32. Domestic violence |

tbl, 1995 |

Review of evaluations of battered treatment programs. |

|

|

33. Domestic violence |

Rosenfeld, 1992 |

Review of battered treatment programs focusing on recidivism data. |

25 studies |

|

34. Domestic violence |

Sanders and Azure, 1989 |

Review of various family violence interventions, including services to prevent child abuse and domestic abuse. |

|

|

35. Domestic violence |

Dolman and Eldest, 1995 |

Review of effectiveness of battered treatment programs. |

|

|

SOURCE: Committee on the Assessment of Family Violence Interventions, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 1998. |

|||

this pool of evaluation studies and additional review articles represents a foundation of research knowledge that will guide the next generation of family violence evaluation efforts and allows broad lessons to be derived from the research literature. For example, research evaluations of the treatment of sexually abused children have concluded that therapeutic treatment is beneficial for many clients, although much remains unknown about the impacts and interactions associated with specific treatment protocols or the characteristics of children and families who are responsive or resistant to therapeutic interventions (Finkelhor and Berliner, 1995). The knowledge base also provides insight into the difficulties associated with implementing innovative service designs in various institutional settings and the range of variations associated with clients who receive family violence interventions in health care, social service, and law enforcement settings.

Sample Size and Statistical Power

Studies of family violence interventions are often based on small samples of clients that lack sufficient statistical power to detect meaningful effects, especially when such effects are distributed nonrandomly across the subject population and do not persist over time. Statistical power is the likelihood that an evaluation will detect the effect of an intervention, if there is one. Two factors affect statistical power: sample size and effect size (the effect size, ES, is usually measured in terms of the mean difference between the intervention and control groups as a fraction of the standard deviation). In designing an evaluation, researchers need to consider the effect size that would be needed to achieve satisfactory statistical power (power is commonly deemed adequate when there is an 80 percent chance of detecting a hypothesized result).

Conventional statistical estimates suggest that large effects of an intervention (an effect size that exceeds 0.80) require a sample size of at least 20 individuals. This sample size is the modal size used in child abuse studies reported in a review by Finkelhor and Berliner (1995). These studies would have to posit large differences between innovative services and usual care to observe program effects. As the meaningful effect size becomes smaller, a larger sample size is needed to detect it. Medium effects (ES = 0.50) require a sample size of at least 80 individuals to observe the effect, if it exists. Small effects (ES = 0.20), which may be important in terms of understanding the types of individuals who respond positively or negatively to specific interventions, require larger sample sizes of 300 or more to observe the effects, if they exist (Cohan, 1988). Few family violence intervention studies reported to date have used samples this large.

Calculating the actual statistical power for each sample size and the ''expected effect" scenario represents an important measure of the statistical adequacy of family violence studies. For example, an intervention that is expected to produce a medium effect and involves 20 clients per group has only a 46

percent chance of detecting the effect (if it exists). To reach conventional levels of power (80 percent), the sample sizes should be increased fourfold to 80 per group to detect medium and large effects. If the true effect is small, a 15-fold increase in the sample size would be necessary.

The use of multisite evaluations can increase the statistical strength of family violence intervention studies, as long as separate sites adhere to common design elements of the intervention and apply uniform eligibility and risk assessment criteria (difficulties in these areas have been identified in at least one evaluation of intensive family preservation services—see Schulman et al., 1994). An alternative is to extend the duration of each study to allow sufficient time to accrue an appropriate sample. But expanding the time frame increases the possibility that the intervention may be revised or changes may occur in the subject population or the community.

Lessons from Nonexperimental Studies

Limitations in the caliber of study designs, the weak statistical power of the majority of studies, and inconsistencies in the reliability and validity of measures suggest that little firm knowledge can be extracted from the existing literature about program effects of family violence interventions. However, in the committee's view, the evaluations described in Tables 3-1 and 3-2 provide information about obstacles that need to be addressed and successes that could be built on. Although pre-post, nonexperimental studies cannot provide solid inferences about net effects, they are important predecessors to the next generation of studies. These building blocks in the developmental process include experience with the stages of program implementation, awareness of the utility of screening measures and their sensitivity to change over time, estimates of the reliability and validity of selected research measures, and experience with recruitment and attrition in the intervention condition and measurement protocol.

These technical problems, which involve fundamental principles of what constitutes a good study design and methods, are similar to those that plague many studies of social policies. But they are overshadowed by other, more pragmatic issues related to subject recruitment and retention, ethical and legal concerns, and the integration of evaluation and program development. These pragmatic issues, discussed in the next section, require attention because they can interact with study design and methods to strengthen or weaken the overall strength of evaluation research.

Points Of Collaboration Between Researchers And Service Providers

Several steps are necessary to resolve the technical challenges alluded to above. First, research and evaluation need to be incorporated earlier into the

program design and implementation process (National Research Council, 1993b). Second, such integration requires creative collaboration between researchers and service providers who are in direct contact with the individuals who receive interventions and the institutions that support them. The dynamics of these collaborative relationships require explicit attention and team-building efforts to resolve different approaches and to stimulate consensus about promising models of service delivery, program implementation, and outcomes of interest. Third, the use of innovative study designs (such as empowerment evaluations, described later in this chapter) can provide opportunities to assess change associated with the impact of programs, interventions, and strategies (Letterman et al., 1996). Drawing on both qualitative and quantitative methods, these approaches can help service providers and researchers share expertise and experience with service operation and implementation.

Numerous points in the research and program development processes provide opportunities for collaboration. Service providers are likely to be more responsive if the research improves the quality and efficiency of their services and meets their information needs. Addressing their needs requires a reformulation of the research process so that researchers can provide useful information in the interim for service providers while building a long-term capacity to focus on complex issues and conducting experimental studies.

Knowledge About Usual Care1

The first point of collaboration between research and practice occurs in the development of information about the nature of existing services in the community. If the elements of service delivery that are represented by normal or usual care are not known, then the extent to which innovative interventions differ from or resemble usual care cannot be assessed. If the experimental condition does not involve a substantially greater or different amount of service, then the experiment will degrade to a test of the effects of similar service levels; it will become difficult to distinguish equivalent effects from no beneficial impact in the evaluation of the treatment under study. This type of study may lead to conclusions that the new intervention is ineffective, when in fact it does not differ significantly from usual care.

In his assessment of family preservation services, Ors (1992) notes that, although usual care circumstances generally involve less service than is delivered in intensive family preservation programs, families who do not receive the intensive services rarely receive no service at all. Without knowing more precisely the magnitude and quality of the differences between the treatment and control conditions, estimates of effects are difficult to interpret. Findings of no difference (which are common in many social service areas) can result from insufficient

service distinctions among conditions and groups, as well as small sample sizes (Lisped, 1990). In some cases, degraded differences between groups play a larger role in loss of statistical power than reductions in sample size (Corduroy and Pin, 1993).

Program Implementation

A second point of collaboration between researchers and service providers occurs in developing knowledge about the nature and stages of implementation of the intervention being tested. This assessment requires attention to client flow, rates of retention in treatment, organizational capacity (how many clients can be served), and features that distinguish the treatment from usual care circumstances. Knowledge about program implementation also requires articulation of the "logic model" or "theory of change" that provides a foundation for the services that are provided and how they work together to serve the client.

The reliability and the validity of outcome measures consume a great deal of attention in the evaluation literature. Of equal importance are the reliability and the validity of the service delivery system itself and the ways in which intervention services compare with those provided in the usual-care or no-treatment conditions. Measurement of service delivery features provides a basis for transporting successful interventions to other locations, and it offers an opportunity to provide assistance to program developers in monitoring the delivery of services.

Conducting a randomized assessment of an intervention that is poorly implemented is likely to show, with great precision, that the intervention did not work as intended. But such a study will not distinguish between failures of the theory that is being tested and failures of implementation. Program designers need to identify critical elements of programs to explain why effects occurred and to assist others who wish to replicate the intervention model in a new setting. Collaboration between researchers and program staff is thus essential to incorporate attention to the experience with program design and implementation into the overall evaluation plan.

Client Referrals, Screening, and Baseline Assessment

A third point of collaboration between researchers and service providers occurs in the development of knowledge about paths by which clients are referred, screened, and assigned to treatment or control conditions. This area focuses on knowing more about the entire context, structure, and operation of the program throughout all its stages—from the moment an individual is identified as a potential client to his or her last recorded contact with the program. Such knowledge can improve evaluations of family violence interventions by providing strategies on how to enhance sample sizes yet stay within the eligibility criteria established by the program. Research on the client selection and assessment

processes can make more explicit the social, economic, legal, and political factors that affect the paths by which individuals self-select or are referred to family violence programs in health, social service, and law enforcement settings. Research on the pathways to service can reveal the extent to which service providers can adjust their programs and interventions to the specific characteristics of their clients. It can also clarify the extent of common characteristics and variation among clients.

Clients who enter these programs have varying histories of abuse, life circumstances, financial resources, and experiences with support networks and service agencies. Capturing these individual differences at the point of baseline (preintervention) assessment allows the research study to examine the extent to which interventions have different impacts with different groups of clients. At a minimum, baseline assessment (and assignment) could be used to enhance the sensitivity of the overall design by taking into account known risk factors that can be used to reduce the influence of extraneous outcome variance.

Collaborations directed at refining the assignment process can clarify the threats to validity that arise in client selection processes when randomization is not possible or cannot be maintained. Researchers who focus on devising strategies to improve client selection will need to collaborate with caseworkers, police officers, district attorneys, judges, and other individuals who routinely work with victims at key points in the usual circumstances. Such collaborations can lead to novel approaches to assigning individuals to service conditions, which currently are not well documented in the research literature.

Discussions between researchers and practitioners can also identify important considerations that arise from the need to look at the population who are served versus those who were eligible for service but were not included in the study design. Science-based efforts to maintain rigorous and consistent eligibility criteria can sometimes result in an incomplete picture of the characteristics of the general client base, which are often familiar to the community of service providers. When clients who have multiple problems (such as substance abuse, chronic health or mental health disorders, family emergencies, or criminal histories) are routinely screened out of a study, for example, a program may appear to be effective for the service population when in reality it is being assessed for only a limited portion, and possibly the most receptive portion, of the client population. Conversely, when eligibility standards are less strict, an intervention may appear to be ineffective for the general population who receive services (who may not actually need the intervention that is provided). The creation of specific cohorts within a study design can facilitate analysis of the relative impact of the intervention in high- and low-risk groups, but such efforts require general consensus about characteristics and histories that can provide consistent markers to justify assignment to different groups.

Discussions of random assignment in evaluations of service interventions often raise concerns about the fairness or safety of denying services to some

individuals for the purpose of devising a control condition. Control group issues are especially difficult in assessing ongoing interventions that try to serve all comers. Although withholding services to victims of violence for the purpose of devising a control condition is not justifiable, the rejection of random or controlled assignment of clients is not warranted. Since most intervention studies involve comparisons with usual-care circumstances, those who are assigned to this control group will receive the types and levels of services that they would have received in the absence of the intervention condition. As such, control clients receive customary services, but they do not receive services with untested benefits or uncertain risks, which may be superior or inferior to the standard of usual care.

In other situations, randomization can be employed in cases in which there is uncertainty about the nature of services to be provided. This "tie-breaker" approach has been used in law enforcement studies in which the officer in charge could randomly assign borderline cases to a treatment or control group as part of the design of the research study (Lisped et al., 1981).

Descriptive evaluation studies identify key issues, such as the likely scope of the treatment population and the likely sources of referrals for these clients (Lisped et al., 1981). Such studies can also help identify factors in the sociopolitical context of family violence interventions that influence service design and implementation. These "pipeline" studies can be an important part of the program and evaluation planning process (Borsch, 1994) and represent opportunities for researcher and service provider collaborations that are not well documented in the research literature.

In testing the impact of new service systems, the use of wait-list controls is another option that can be considered in the study design. For example, the Women's Center and Shelter of Greater Pittsburgh reported that they could not meet the request for services in their community. In this instance, a wait-list control may have been justified in the evaluation of the impact of shelter services. However, this approach does not resolve the problem and tensions associated with using limited fiscal resources to study, rather than extend, existing services. A variation of the use of wait-list controls is an approach that relies on a triage process to identify those most in danger, provide full services for them, and use random assignment for those in less danger. This approach may be most tolerable when a waiting list for services and a wait-list control group (or step) design can be used.

Another approach to experimental assessment involves the use of alternative forms of service, which can be distinguished in terms of their intensity, duration, or comprehensiveness. Individuals in need of services would receive (in a controlled fashion) alternative service models or administrative procedures. This approach is less appealing when alternative service models cannot be easily distinguished, since decreases in variation will influence the researchers' ability to detect small but meaningful impacts and relative differences among alternative

treatment systems. The absence of differences in studies of alternative forms of service can be interpreted as showing that interventions do not have their intended effects (i.e., they are unsuccessful) or that both approaches are equally effective in enhancing well-being. The absence of a framework for assessing change over time will impede efforts to distinguish between no beneficial effects and equivalent effects.

The Value of Service Descriptions

Collaborative research and practice partnerships can highlight significant differences between new services and usual-care services, which are generally a matter of degree. Treatment interventions may differ in terms of frequency (number of times delivered per week), intensity (a face-to-face meeting with counselors versus a brief telephone contact), or the nature of the activities (goal setting versus establishment of a standard set of expectations). Documenting these differences is critical for planning and interpreting the outcome and replication, since they establish the strength of the intervention.

The value of service descriptions is enhanced by identifying key elements that distinguish interventions from comparison groups as well as ones they have in common. Such descriptions should include information about the setting(s) in which service activities occur; the training of the service provider; the frequency, intensity, and/or duration of service; the form, substance, and flexibility of the program (e.g., individual or group counseling); and the type of follow-up or subsequent service associated with the intervention.

Most family violence interventions are poorly documented (Heneghan et al., 1996; Ors, 1992). For example, in 10 evaluation studies of intensive family preservation services reported by Heneghan et al. (1996), all 10 described (in narrative form) the types of services that were provided, but only 5 provided data on the duration of services; 3 provided data on the number of contacts per week; and 3 provided limited, narrative information on services provided in the usualcare conditions. In a different study, Median and Hanse (1985) found that the majority of abuse cases that were substantiated received no services at all (see Chapter 4). This point highlights the importance of knowing more about significant differences between service levels in the treatment and comparison groups, so that innovative projects do not duplicate what is currently available.

The flexibility in services is also an issue in assessing differences in service levels. Some services are protocol driven, whereas others can be adjusted to the needs of specific clients. The most respected intervention evaluations use consistent program models that can be replicated in other sites or cities. However, most interventions in social service, health, and law enforcement settings aim to be responsive to individual client needs and profiles rather than driven by protocols because of the variation in the individual experiences of their clients. Safety planning for battered women, for example, varies tremendously depending on

whether a woman plans to stay in an abusive relationship, is planning to leave, or has already left. Staff, clients, and researchers can collaborate to prepare multiple protocols for a multifaceted intervention that reflects the context and setting of the service site.

Finally, many intervention efforts presume that a social ill can be remedied through the application of a single dose of an intervention (e.g., 3 weeks of rehabilitation). Others rely on follow-up activities to sustain the gains made in primary intervention efforts. Careful description of differences in follow-up activities should be given as much attention as is given to describing the primary intervention.

Explaining Theories of Change

In the early stages of development, the fundamental notions or theoretical concepts that guide a program intervention are not always well articulated. However, the service providers and program developers often share a conceptual framework that reflects their common understanding of the origins of the problem and the reasons why a specific configuration of services should remedy it. Extracting and characterizing the theory of change that guides an intervention can be a useful tool in evaluating community-based programs (Weirs, 1995), but this approach has not been widely adopted in family violence evaluations.

Program articulation involves a dynamic process, involving consultation with program directors, line staff, and participants throughout the planning, execution, and reporting phases of the evaluation (Hen and Ors, 1983; Corduroy, 1993; US. General Accounting Office, 1990). Causal models provide a basis for determining intermediate outcomes or processes that could be assessed as part of the overall evaluation plan. If properly measured, these linkages can provide insights into why interventions work and what they are intended to achieve.

Outcomes and Follow-up

Front-line personnel often express concerns that traditional evaluation research, which relies on a single perspective or method of assessment, may measure the wrong outcome. For example, evaluations of shelters for battered women may focus on the recurrence of violence, which is usually dependent on community sanctions and protection and is out of the victim's and the shelter's control. The reliance on single measures can strip the entire enterprise, as well as victims' lives, of their context and circumstances. Another issue of concern is that outcomes may get worse before they get better. For instance, health care costs may increase in the short term with better identification and assessment of family violence survivors.

An important strategy is to measure many and different outcomes, immediate and long-term outcomes, multiple time periods, both self-report and observational

measures, and different levels of outcomes. The absence of consensus about the unique or common purposes of measurement should not obscure the central point that the identification of relevant domains for measuring the success of interventions requires an open collaborative discussion among researchers, service providers, clients, sponsors, and policy makers.

Another key to improving data collection, storing, and tracking capabilities is the development of coordinated information systems that can trace cases across different service settings. Three national data systems for child welfare data collection provide a general foundation for national and regional studies in the United States: in the Department of Health and Human Services, the Administration on Children and Families' Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (EFFACERS); the federally supported and optional Statewide Automated Child Welfare Information Systems (SACCUS); and the National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect's National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NANDS), a voluntary system that includes both summary data on key indicators of state child abuse and neglect indicators and detailed case data that examine trends and issues in the field. Researchers are now exploring how to link these data systems with health care and educational Dataquest, using record-matching techniques to bring data from multiple sources together (George et al., 1994a). This type of tracking and record integration effort allows researchers to examine the impact of settings on service outcomes. Using this approach, Wulczyn (1992), for example, was able to show that children in foster care with mothers who had prenatal care during their pregnancy had shorter time periods in placement than children whose mothers did not have prenatal care. Similarly, drawing on foster care Dataquest and the records of state education agencies, George et al. (1992) reported that 28 percent of children in foster care also received various forms of special education. Fostering links between Dataquest such as NANDS and EFFACERS and other administrative record sets will require research resources, coordination efforts, and the use of common definitions. Such efforts have the potential of greatly improving the quality of program evaluations.

Community Context

The efficacy of a family violence intervention may depend on other structural processes and service systems in the community. For instance, the success of battered treatment (and the evaluation of attrition rates) is often dependent on the ability of criminal justice procedures to keep the perpetrator in attendance. Widespread unemployment and shortages in affordable housing may undermine both violence prevention and women's ability to maintain independent living situations after shelter stays. Evaluation outcomes therefore need to be analyzed in light of data collected about the community realities in which they are embedded.

A combination of qualitative and quantitative data and the use of triangulation

can often best resolve the need to capture contextual factors and control for competing explanations for any observed changes. Triangulation involves gathering both qualitative and quantitative data about the same processes for validation, and complementing quantitative data with qualitative data about other issues not amenable to traditional measurement is recommended. Agency records can be analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively.

At a minimum, regardless of the measures that are chosen, the ones selected ought to be assessed for their reliability (consistency) and validity (accuracy). There is a surprising lack of attention to these issues in the family violence field, although a broad range of measures is currently used in program evaluations (Table 3-3).

The Dynamics Of Collaboration

Strengthening the structural aspects of the partnership between researchers and service providers will change the kinds of relationships between them. Creative collaborations require attention to several issues: (1) setting up equal partnerships, (2) the impact of ethnicity and culture on the research process, (3) safety and ethical issues, and (4) concerns such as publishing and publicizing the results of the evaluation study and providing services when research resources are no longer available.

Equal Partnerships

Tensions between service providers and researchers may reflect significant differences in ideology and theory regarding the causes of family violence; they may also reflect mutual misunderstandings about the purpose and conduct of evaluation research. For front-line service providers, evaluation research may take time and resources away from the provision of services. The limited financial resources available to many agencies have created situations in which finances directed toward evaluation seem to absorb funds that might support additional services for clients or program staff. Evaluations also have the potential to jeopardize clients' safety, individualization, and immediacy of access to care.

Recent collaborations and partnerships have gone far to address these concerns. Community agencies are beginning to realize that well-documented and soundly evaluated successes will help ensure their fiscal viability and even attract additional financial resources to support promising programs. Researchers are starting to recognize the accumulated expertise of agency personnel and how important they can be in planning as well as conducting their studies. Both parties are recognizing that, even if research fails to confirm the success of a program, the evaluation results can be used to improve the program.

True collaborative partnerships require a valuing and respect for the work on all sides. Too often the attitude of researchers in the past has been patronizing

TABLE 3-3 Outcome Measures Used in Evaluations of Family Violence Interventions

|

Type of Violence |

Instrument |

Subject of Outcome Measure |

|

|

|

|

|

Victim |

Perpetrator |

Other |

|

Child Abuse |

Adolescent-Family Inventory Events |

|

X |

|

|

|

Adult/Adolescent Parenting Inventory |

|

X |

|

|

|

Chemical Measurement Package |

|

X |

|

|

|

Child Abuse Potential Inventory |

|

X |

|

|

|

Child and Family Well-Being Scales |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Child Behavior Checklist |

X |

|

|

|

|

Conflict Tactics Scales |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Coppersmith Self-Opinion Inventory |

|

X |

|

|

|

Coping Health Inventory |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scales |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Family Assessment Form |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Family Environment Scale |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Family Inventory of Life Events and Changes |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Family Systems Outcome Measures |

|

|

X |

|

|

Home Observation |

|

|

X |

|

|

Cent Infant Development Scale |

X |

|

|

|

|

Maternal Characteristics Scale (Right) |

|

X |

|

|

|

Minnesota Child Development Inventories |

X |

|

|

|

|

Parent Outcome Interview |

|

X |

|

|

|

Parenting Stress Index |

|

X |

|

|

Domestic Violence |

Adult Self-Expression Scale |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Conflict Tactics Scales |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Depression Scale CEOs-D |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Quality of Life Measure |

X |

|

|

|

|

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Rooter Internal-External Locus of Control Scale |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Social Support Scale |

X |

|

|

|

Elder Abuse |

Anger Inventory |

|

X |

|

|

|

Brief Symptom Inventory |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale |

X |

X |

|

|

SOURCE: Committee on the Assessment of Family Violence Interventions, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 1998. |

||||

toward activists, and front-line agency personnel have been suspicious of researchers' motives and commitment to the work. Honest discussion is needed of issues of parity, all the possible gains of the enterprise for all parties, what everyone would like out of the partnership, and any other unresolved issues. Both sides need to spend time observing each other's domains, in order to better realize their constraints and risks.

The time constraints associated with setting up partnerships, especially those associated with short deadlines for responding to requests for proposals, need attention. Rather than waiting for a deadline, service providers and researchers need to support a plan for assessing the effects of interventions early in their development.

Viable collaborations also involve the consumers of the service at every step of the evaluation process. Clients can suggest useful outcome variables, the contextual factors that will modify those outcomes, elements of theory, and strategies that will maximize response rates and minimize attrition. They can help identify risks and benefits associated with the intervention and its evaluation.

Finally, collaboration that leads to a common conceptual framework for the evaluation study and intervention design is an essential and productive process that can identify appropriate intermediate and outcome measures and also reconcile underlying assumptions, beliefs, and values (Conned et al., 1995).

The Impact of Ethnicity and Culture

Ethnicity and culture consistently have significant impact on assessments of the reliability and validity of selected measures. Most measures are tested on populations that may not include large representation of minority cultural groups. These measures are then used in service settings in which minorities are often overrepresented, possibly as a result of economic disadvantage.

The issues of ethnicity and cultural competence influence all aspects of the research process and require careful consideration at various stages. These stages include the formation of hypotheses taking into account any prior research indicating cultural or ethnic differences, careful sampling with a large enough sample size to have enough power to determine differential impact for different ethnic groups, and strategies for data analysis that take into account ethnic differences and other measures of culture.

Improving cultural competence involves going beyond cultural sensitivity, which involves knowledge and concern, to a stance of advocacy for disenfranchised cultural groups. The absence of researchers who are knowledgeable about cultural practices in specific ethnic groups creates a need for greater exposure to diverse cultural practices in such areas as parenting and caregiving, child supervision, spousal relationships, and sexual behaviors. This approach requires greater interaction with representatives from diverse ethnic communities in the

research process as well as agency services to foster a cultural match with the participants (Williams and Beaker, 1994).

In analyzing of the effect of social context on parenting, caregiving behaviors, and intimate relationships, greater attention to culture and ethnicity is advisable. Evaluating the role of neighborhood and community factors (including measures such as social cohesion, ethnic diversity, and perceptions by residents of their neighborhood as a ''good" or "bad" place to raise children) can provide insight into the impact of social context on behaviors that are traditionally viewed only in terms of individual psychology or family relationships.

Safety and Ethics

Safety concerns related to evaluation of family violence interventions are complex and multifaceted. Research confidentiality can conflict with legal reporting requirements, and concern for the safety of victims must be paramount. Certificates of confidentiality are useful in this kind of research, but they simply shield the researcher from subpoena and do not resolve the problems associated with reporting requirements and safety concerns. Basic agreements regarding safety procedures, disclosure responsibilities, and ethical guidelines need to be established among the clients, research team, service providers, and individuals from the reporting agency (e.g., child or adult protective services) to develop strategies and effective relationships.

Exit Issues

Ideally the research team and the service agency will develop a long-term relationship, one that can be sustained, through graduate student involvement or small projects, between large formal research studies. Such informal collaborations can help researchers in establishing the publications and background record needed for large-scale funding. Dissemination of findings in local publications is also helpful to the agency.

Formal and informal collaboration requires that all partners decide on authorship and the format of publication ahead of time. Multiple submissions for funding can attract resources to carry out some aspects of the project, even if the full program is not externally funded. The collaboration also requires thoughtful discussions before launching an evaluation about what will be released in terms of negative findings and how they will be used to improve services.

One exit issue often not addressed is the termination of health or social services in the community after the research is completed. Innovative services are often difficult to develop in public service agencies if no independent source of funds is available to support the early stages of their development, when they must compete with more established service strategies. Models of reimbursement and subsidy plans are necessary to foster positive partnerships that can

sustain services that seem to be useful to a community after the research evaluation has been completed.

Evaluating Comprehensive Community Initiatives

Family violence interventions often involve multiple services and the coordinated actions of multiple agencies in a community. The increasing prevalence of cross-problems, such as substance abuse and family violence or child abuse and domestic violence, has encouraged the use of comprehensive services to address multiple risk factors associated with a variety of social problems. This has prompted some analysts to argue that the community, rather then individual clients, is the proper unit of analysis in assessing the effectiveness of family violence interventions. This approach adds a complex new dimension to the evaluation process.

As programs become a more integrated part of the community, the challenges for evaluation become increasingly complex:

- Because participants receive numerous services, it is nearly impossible to determine which service, if any, contributed to improvement in their well-being.

- If the sequencing of program activities depends on the particular needs of participants, it is difficult to tease apart the effects of selectivity bias and program effects.

- As intervention activities increasingly involve organizations throughout the community, there is a growing chance that everyone in need will receive some form of service (reducing the chance of constituting an appropriate comparison group).

- As program activities saturate the community, it is necessary to view the community as the unit of analysis in the evaluation.

- The tremendous variation in individual communities and diversity in organizational approaches impede analyses of the implementation stages of interventions.