1

Introduction

With great speed and a considerable amount of controversy, managed care has produced dramatic changes in American health care. At the end of 1995, 161 million Americans—more than 60 percent of the total population— belonged to some form of managed health care plan (HIAA, 1996a). The movement into managed care has been especially rapid for the treatment of mental health and substance abuse (alcohol and drug) problems, also known as behavioral health. Behavioral health problems are common: every year, an estimated 52 million Americans have some kind of mental health or substance abuse problem (see Table 1.1). At the end of 1995, the behavioral health benefits of nearly 142 million people were managed, with 124 million in specialty managed behavioral health programs and 16.9 million in an HMO (Open Minds, 1996).

Health maintenance organizations (HMOs), preferred provider organizations (PPOs), point-of-service plans, and other forms of managed care networks, such as managed behavioral health care organizations, differ in their organizational structures, types of practitioners and services, access strategies, payment for practitioners, and other features. Their goals, however, are similar: to control costs through improved efficiency and coordination, to reduce unnecessary or inappropriate utilization, to increase access to preventive care, and to maintain or improve the quality of care (IOM, 1996a; Miller and Luft, 1994).

Both private-sector employers and public-sector agencies (Medicaid and state mental health and substance abuse authorities) have turned to managed behavioral health care companies to control costs and improve quality and access for mental health and substance abuse care. Traditionally, mental health and substance abuse care benefits have been more limited compared with benefits for

TABLE 1.1 Estimated Annual Prevalence of Behavioral Health Problems in the United States (Ages 15–54)

|

Behavioral Health Problems |

Prevalence (percent) |

No. of People (millions) |

|

All behavioral health problems (i.e., mental disorders, alcoholism, and drug addiction) |

29.5 |

52 |

|

Any mental disorder |

22.9 |

40 |

|

Any substance abuse or dependence (i.e., alcohol and illicit drugs) |

11.3 |

20 |

|

Both mental disorder and substance abuse or dependence |

4.7 |

8 |

|

NOTE: Prevalence data have been collected from the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), a Congressionally mandated survey designed to study the comorbidity of substance use disorders and nonsubstance use-related psychiatric disorders in the United States. The survey was administered by the staff of the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan between 1990 and 1992. NCS surveyed 8,098 noninstitutionalized participants with a structured psychiatric interview conducted by lay interviewers using a revised version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). CIDI is a structured diagnostic interview based on the National Institute of Mental Health's (NIMH's) Diagnostic Interview Schedule, which can be used by trained interviewers who are not clinicians (Kessler et al., 1994). SOURCE: Kessler et al. (1994) and SAMHSA (1995). |

||

physical health, and for mental health and substance abuse care there also have been few alternatives to hospitalization. In the late 1980s, the majority (70 percent) of mental health funds spent by Medicaid and private insurance went for inpatient care, leading many researchers, clinicians, and advocates to question the imbalance and to search for policy changes. Only the introduction of managed care arrangements has led to a significant shift away from costly and often unnecessary inpatient stays to a more appropriate range of outpatient and community-based care. In sum, behavioral health care offers purchasers the potential to spread existing resources farther by paying for less intensive (and less expensive) treatment strategies that can return patients to a reasonable level of functioning, such as being able to return to work or school (England and Vaccaro, 1991).

The controversies in managed care are less about the goal of cost reductions and are more about the ways in which cost reductions are achieved. Methods of cost control include authorizing only certain practitioners who are under contract to provide services to an enrolled population, reviewing treatment decisions, closely monitoring high-cost cases, reducing the number of days for inpatient hospital stays, and increasing the use of less expensive alternatives to hospitalization (Iglehart, 1996; Shore and Beigel, 1996).

In the committee's view, managed care strategies are not inherently harmful

and can be appropriate and helpful, as in the shift from inpatient to outpatient care, the additional supervision for complex cases, and applications of standards based on best practices. However, certain activities of companies that provide behavioral health care, such as limiting or denying services that are considered to be needed, adding barriers to access to care such as increased copayments for outpatient visits, and adding gatekeepers who change the practitioner-patient relationship, are viewed as having an adverse impact on the quality of care (Mechanic et al., 1995).

The overall impact of managed care on the quality of health care is difficult to determine. Managed care has many structures, making comparisons across organizational forms (e.g., HMOs vs. PPOs) difficult. In addition, the quality of health care is difficult to measure and define because of the complexity of health care. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has defined quality of care as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (IOM, 1990a, p. 21).

|

Definition of Quality of Care The degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge (IOM, 1990a, p. 21). |

Adopting this definition would suggest an array of health services research based on the variations of each component: health services (e.g., primary care and specialty drug abuse, alcoholism, and mental health treatment in different practice settings, including hospital-based and office-based practices and health centers), individuals (e.g., differences among children, adolescents, adults, and seniors, as well as gender differences), populations (e.g., cultural differences and differences between rural and urban populations), and outcomes (e.g., cure, relapse prevention, and return to functioning). The combinations are virtually unlimited.

Public interest in quality of care is keen, and purchasers are not waiting for conclusive outcomes research to help them make decisions on the value and effectiveness of different managed care options. HMO ratings, adapted from product and service rating systems such as those developed by Consumer Reports, are published in national magazines such as Time, U.S. News and World Report, and Newsweek and in national newspapers including The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and USA Today. Report cards and ratings are produced by managed care organizations, governments, purchaser coalitions, and trade organizations,

emphasizing consumers' satisfaction with their care and the services that they have received.

|

The challenge of accountability studies is how to build report cards that report consistent, credible, and verifiable data back to the patients and the people who are trying to pick which HMO or PPO they 're going to join. Randall Madry Utilization Review Accreditation Commission Public Workshop, May 17, 1996, Irvine, CA |

When these new measures of health care quality are added to the traditional approaches, primarily accreditation and licensure of practitioners and facilities, quality assessment becomes a complex patchwork of mechanisms. Federal, state, and local governments, accreditation organizations, managed care organizations, purchaser coalitions, consumer groups, professional organizations, and the media are actively involved in providing information on the quality of health care. Some of these efforts are collaborative, but some are competitive. Overall, the picture is incomplete, inconsistent, and inadequate for making truly informed decisions about the quality of health care services. To those who are responsible for purchasing care, the absence of consensus on quality measurement makes decisions more difficult.

In the spring of 1995, the IOM was asked by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to convene a committee to examine quality assurance and accreditation guidelines for managed behavioral health care. The committee's charge was to provide a framework to guide the development, use, and evaluation of performance indicators, accreditation standards, and quality improvement mechanisms in managed behavioral health care (i.e., services related to mental health, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse). In carrying out this task, the committee operated on a clear premise: the ultimate goal of the work was to improve the quality of care for people with behavioral health problems.

Although many of the committee's concerns about the quality of behavioral health care are unique, any study of accreditation and other quality assurance strategies also has relevance to the general health care system. The processes of accreditation and quality assurance are fundamentally the same in the primary care and specialty sectors, and the role of primary care practitioners contributes to the evaluation and delivery of behavioral health care. Furthermore, all sectors of the health care delivery system are responding to the same demands from policymakers and the public for accountability and cost-effectiveness.

|

When you think about it, every organization—be it a managed care organization, an insurer, a hospital, an integrated delivery system, whatever—has huge financial systems that literally aggregate and track hundreds if not thousands of financial transactions, On the quality side, we pull 10 charts and do a review. John Bartlett American Managed Behavioral Healthcare Association Public Workshop, April 18, 1996, Washington, DC |

Six themes emerged from the committee's review of the research and industry literature. The themes were echoed and amplified in the testimony from individuals from the managed behavioral health care industry, accreditation organizations, professional associations, and advocacy groups; consumers; and health policy analysts. They are as follows:

-

Behavioral health problems include a wide range of conditions whose effects may be short-lived or lifelong and that may be mildly distressing or profoundly disabling. Many conditions are chronic and relapsing. Most can be effectively treated and respond to appropriate and ongoing care.

-

Treatment is most successful when it matches an individual's needs and includes an array of integrated services, including primary care, specialty mental health and substance abuse care, and community-based care, such as social support programs.

-

Behavioral health care is changing rapidly and profoundly, stimulated primarily by the introduction and evolution of managed care and by the discovery of new and effective medications and other treatments.

-

The influence of managed care will continue to grow. Administered appropriately, it can provide quality care at reasonable cost. Without careful attention, it can result in the undertreatment and neglect of some of the most vulnerable individuals.

-

The complex patchwork of quality measures and accreditation mechanisms has yet to produce significant progress in the effort to improve the quality of care, but it is laying a foundation of performance measures and accreditation standards that may ultimately serve that purpose.

-

Differences in perspectives and differences in the timing of and strategies for treatment make it difficult to find a set of measures of the quality of behavioral health care services that all stakeholders can agree on.

|

If we really focused on patient/client-driven, assessment-based, clinically-driven treatment in the most efficient and effective way, based on accountability and data, that would take care of costs. David Mee-Lee American Society on Addiction Medicine Public Workshop, April 18, 1996, Washington, DC |

This final point must be emphasized. A combination of factors—including the expected outcome, the time at which treatment effects are measured, and the perspective of the individual consumers and practitioners—can produce dramatically different conclusions. Confronted with a patient with suicidal depression, for example, a psychiatrist might judge treatment as high quality if that patient no longer has suicidal thoughts after a week in the hospital. The patient's mother, on the other hand, may be disappointed with the hospitalization even if she is pleased that her son was released so soon and denies suicidal thoughts. She may feel that the resident psychiatrist was inexperienced, that the attending psychiatrist doubted her account of the potential reasons for her son's crisis, and that the underlying causes of his problem were not addressed. This same set of circumstances could occur in both fee-for-service and managed care settings, although the next steps for reviewing the treatment decisions might be very different.

Despite such challenges, the committee believes that all of the stakeholders —consumers, practitioners, public and private purchasers, managed care companies, accreditation organizations, and other citizens and groups with a stake in the quality of care—can and must work together to reach a coordinated, collaborative, and consensus approach to quality measurement and treatment. The committee believes that efforts to achieve consensus, both on definitions and on measures of quality, are a valuable investment in the effort to provide the best possible treatment at the lowest appropriate cost.

The development of consensus on quality is particularly important in the field of behavioral health for a variety of reasons that will be discussed throughout this report. Both the complexity of health care and the number of stakeholders have grown extremely rapidly. In the field of behavioral health, the growth in complexity can be attributed to at least four factors:

-

Increased scientific knowledge about the effectiveness of treatment and the proliferation of new treatment methods give both primary care and specialty practitioners an opportunity to treat these problems.

-

More publicity, greater public understanding, availability of insurance, and less stigma associated with behavioral health conditions result in increased

-

numbers of people seeking treatment and give purchasers new incentives to control their costs.

-

Differences in the structure of insurance coverage for behavioral health care compared with that for physical health care, including the continued application of lifetime and annual limits and other restrictions, have drawn the attention of state and federal lawmakers, businesses, lobbies, and advocacy groups that seek parity for behavioral and physical health care coverage.

-

The immense growth in managed care in general and in carve-outs (independent, specialty managed care organizations for behavioral health treatment) changes purchasers' choices and prompts new consumer actions.

What makes the health care system succeed or fail in providing high-quality treatment is the interaction between groups of stakeholders and their views on the system's structure, access to care, outcomes, costs, and other factors. Throughout the committee's deliberations, the perspectives of different stakeholders— consumers and families, practitioners, purchasers, and the managed care industry—were discussed. Different stakeholders provided their perspectives, and each must be considered to provide a context for the committee's observations and recommendations.

|

Will accreditation markedly change the quality of patient care? It may make the system better. It may make the system appear more efficient. But the principal question is, what happens to the patient? Mark Parrino American Methadone Treatment Association Public Workshop, April 18, 1996, Washington, DC |

TERMINOLOGY USED IN THIS REPORT

Managed care takes a philosophical approach different from traditional fee-for-service health care, and its terminology has influenced discussions about quality of care in health economics, public policy, and the media. In these contexts, the term consumer is used to refer to an individual who receives care, who purchases care directly, or who selects among health plans purchased on his or her behalf by an employer or by another entity, such as a professional association or union (the selection is also known as “consumer choice ”). Consumer protection and consumer satisfaction, originally applied in the context of industry products, now can refer to quality assurance and quality improvement in the health care system.

The use of the term consumer is sometimes controversial in primary care and medical specialties, particularly psychiatry, and also in the mental health specialties of psychology, social work, marriage and family therapy, and counseling. Many clinicians view the term as placing undue emphasis on the purchase of health care rather than on the relationship with a practitioner who delivers the care. For example, the 1996 report of the IOM Committee on the Future of Primary Care used the term patient and did not refer to consumers. As Iglehart has described (1996), the application of managed care principles means that practitioners begin to share clinical decisionmaking with payers, insurance plan managers, as well as with consumers, and this is difficult for many practitioners.

In the course of its deliberations, this committee used the term patient in the context of a therapeutic relationship while an individual is receiving care from a clinician, but used the term consumer more broadly to refer to individuals in most circumstances, including individuals who are making purchasing decisions, who are evaluating report cards, or who have already had treatment and are in recovery. This usage is consistent with that of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, including the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Health Care Financing Administration, and SAMHSA. This usage is also consistent with that of four of the accreditation organizations whose activities and standards were reviewed for this report.

The term behavioral health, used throughout this report, is a creation of the managed care industry. The term was developed in private-sector managed care companies in the mid-1980s to describe mental health and substance abuse (abuse of alcohol and other drugs). This term also is controversial, on the grounds that a variety of treatment modalities (e.g., behavioral, cognitive, and psychodynamic modalities) are used, and also on the grounds that the disorders themselves may be physiological or organic rather than simply behavioral manifestations of dysfunction.

Box 1.1 summarizes the terms used in this report. The committee recognizes and respects the variety of uses of these terms, including those used by other IOM committees. In the rapidly changing health care environment, these terms seemed to this committee to be the most applicable for this study of quality assurance in managed behavioral health care.

CONSUMERS AND FAMILIES

Consumers are the ultimate end users of the health care system. The committee defines consumers as individuals who are, have been, or may in the future be receiving care or services (see Box 1.1). In the field of behavioral health care, the term consumer applies to those who are experiencing or have experienced behavioral health problems and illnesses as well as the family members or others who have financial or legal responsibility for their care. Also included are those who are or could be at risk for behavioral health problems and could need care in the future.

|

BOX 1.1 Terminology Used in This Report

Behavioral health: managed care term applied to mental health and substance abuse care and services. Client: an individual who is being treated for mental health or substance abuse problems in a social or rehabilitation setting (e.g., a residential treatment program), or in the private practice of a psychologist, social worker, marriage and family therapist, or counselor. Clinician: an individual who uses a recognized scientific knowledge base and has the authority to direct the delivery of personal health services to patients (IOM, 1996a, p. 33). The term is typically applied in medical settings. Consumer: an individual who is, has been, or may in the future be receiving care or services. Patient: an individual who is cared for by a clinician for purposes of diagnosis, treatment, or preventing illness or for maintaining recovery from illness. The term is usually applied in primary care and specialty medical settings, including psychiatric practice. Practitioner: an individual who delivers clinical, rehabilitation, or psycho-social treatment to individuals in medical, clinical, or social settings. Provider: a program, facility, or organization that delivers health care. Purchaser: a group—such as an employer, unit of government, association, or coalition —that negotiates for and buys health care on behalf of a specified group, generally to cover specific benefits and services at reduced prices. Stakeholders: individuals and groups for whom the cost, availability, accessibility, or quality of care hold direct implications, including individuals who receive care and their families, practitioners, public and private purchasers, managed care companies, accreditation organizations, and policymakers. |

Behavioral health problems are more frequent than is generally realized (see Table 1.1), and their estimated costs to society are far greater than the costs of treatment (see Chapter 3, Challenges in Delivery of Behavioral Health Care). In the past decade, people with behavioral health problems have made great strides

in their efforts to increase access to care and to influence the quality of treatment. Patients and families have grown increasingly sophisticated about scientific advances in treatment and about the types of behavioral health care practitioners, such as knowing which practitioners can prescribe medications. In addition to sponsoring regular meetings of support groups, consumers have taken their cause to legislators in state capitols and the U.S. Congress.

The result has been unprecedented change. For example, for the first time, consumers are working as active partners with practitioners to ensure that their causes are addressed by state and national legislative proposals. One such effort was the proposal by Senators Pete Domenici and Paul Wellstone for parity between physical health and mental health coverage. The original proposal was an amendment to the bill cosponsored by Senators Nancy Kassebaum and Edward Kennedy that was passed by the U.S. Senate in the spring of 1996. The final, compromise version of the bill passed in the fall of 1996 did not mandate any services, required parity only with regard to existing lifetime or annual limits for medical or surgical services, and exempted small businesses. However, advocates view the national discussions about parity as a landmark achievement, and many are actively involved in state parity legislation as well.

At the same time that public awareness of behavioral health issues has increased, the rise of managed care has changed the processes involved in obtaining appropriate treatment. After years of having limited insurance coverage but a selection of practitioners, many consumers now find that their health plan restricts their choice of practitioners and covers only a certain number of visits. Moreover, although a large number of people receive high-quality treatment in managed care plans, high-profile situations involving poor or devastating outcomes have attracted publicity or resulted in litigation.

Families and legal guardians are also concerned about managed care because they face tough and painful decisions when a loved one is or appears to be less willing or able to make rational choices. Caring for a child or other relative with severe mental illness leaves many families financially bankrupt and emotionally devastated. Alcohol and drug abuse also have severe consequences, including loss of family support and neglect of children. Thus, parents and other family members also have a stake in treatment decisions, the structure of care, and insurance coverage.

Advocacy groups have exercised an increasing influence on the structure and quality of care and have been vocal about the importance of client or patient satisfaction with care as a measure of its quality. For example, the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) has recently released a consumer-oriented report card for mental health services in a collaborative effort with many consumers and consumer groups (CMHS, 1996). Advocates are far better organized and influential in the mental health field than in the substance abuse field, where stigma and the fear of prosecution for using illegal substances are powerful deterrents to the open discussion of issues related to quality of care and where traditions of anonymity inhibit advocacy. Reflecting the current climate, in the spring

of 1996 the U.S. Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed legislation (P.L. 104-121, the “Contract With America Advancement Act of 1996”), to disallow Supplemental Security Income and Social Security Disability Insurance to individuals who are disabled only because of drug addiction or alcoholism, or both (i.e., without a disabling psychiatric or medical condition). These steps mean that these individuals will lose federally funded medical coverage as well.

|

We have always had managed care. Until now, we have had what I would call doctor managed care. We are shifting to corporate managed care. The third wave is what I call self-managed care, or self-determination, having a say in the important decisions of one's life. Daniel Fisher National Empowerment Center Public Workshop, April 18, 1996, Washington, DC |

Consumers of behavioral health care are tremendously diverse with respect to family and cultural backgrounds, the nature of their behavioral health problems, type of employment, type of insurance coverage, experiences with practitioners and treatment, philosophies and beliefs about treatment, and many other factors. Some consumers and advocates believe that family involvement in treatment is essential to its success, whereas others believe that involvement with the family will only prolong a person's distress and keep him or her from getting better. All these perspectives must be considered, and they all point to the importance of evaluating each person and family and taking all these variations into account in the development of treatment plans.

PRACTITIONERS

The variety of practitioners in the behavioral health care system adds complexity. In the behavioral health care system, the professional specialty practitioners include psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, psychiatric nurses, social workers, marriage and family therapists, and substance abuse counselors. Primary care physicians also play a significant role in treatment and referrals. In medically underserved areas (especially inner cities and rural and frontier areas), primary care practitioners include a large number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants. In addition, there is a long tradition of social support or self-help groups, starting with Alcoholics Anonymous in the mid-1930s. All these groups share the goal of reducing symptoms and improving the quality of life for individuals and families dealing with behavioral health problems, but the number of different

treatment philosophies and strategies, many of which are conflicting and contradictory and which are recognized by insurers in varying degrees, is staggering.

In substance abuse treatment, counseling is traditionally provided by individuals who are in recovery from alcohol and drug abuse. State administrators and some national professional organizations are concerned that health plans may not view experiential counselors as essential practitioners by health plans and will not provide reimbursements for their services, despite their clinical and cost-effectiveness (NAADAC, 1996). Many states have a long history of supporting the social model programs or nonmedical programs in which these counselors predominate (Gerstein et al., 1994; IOM, 1990b).

A primary motivation for health care practitioners is to help their patients and clients to get better. Improvement can be measured in many ways, including a reduction in symptoms, the ability to return to work or school, improved quality of life, and improved relationships. Ideally, practitioners tailor treatment plans on the basis of a person 's needs and preferences, the availability of appropriate services, and their judgments about what will bring the best results. The realities of health care financing, however, also mean that treatment plans will be developed on the basis of what is paid for by the person 's insurance plan, whether it is a fee-for-service or managed care plan.

|

We have tensions between wanting to individually tailor services and the need for benefit packages. Ann Froio ComCare Public Workshop, May 17, 1996, Irvine, CA |

With managed care, treatment decisions are not only based on the private decisions of practitioners, clients or patients, and the clients' or patients' families. Managed behavioral health care companies in some cases approve a practitioner's treatment plans, so practitioners must disclose confidential information. Clinical protocols standardize treatment, and limitations can be imposed on the numbers and types of sessions, requiring approvals for additional sessions. Some companies emphasize medication management without counseling and psychotherapy, whereas others rely on nonphysician practitioners and use psychiatrists only when prescription medications or hospitalization are needed (Boyle and Callahan, 1993).

Arguably, the resistance to standardization of care is stronger in the behavioral health fields than anywhere else in the health care system. Treatment decisions are complicated by the great variability of conditions, and much remains to be learned about which treatments are most effective for which individuals at which time in the course of their treatment. Many clinicians resist the idea of

standardizing care because of their belief in individual differences —no two people are alike, and the same person behaves differently during different episodes of treatment. The patterns of practice in psychiatry, psychology, psychiatric nursing, and social work include a large proportion of individuals in solo private practice, and they tend to view managed care as a threat to their autonomy and livelihood. The variations in practice, however, would seem to warrant standardization on the basis of evidence of treatment effectiveness.

In the vivid words of one commentator, behavioral health clinicians are sharply divided about whether “to wage a scorched-earth, take-no-survivors holy war against the ‘great Satan' of managed care or to pursue a quality improvement strategy of making managed care better” (Sabin, 1995, p. 32). This practitioner resistance is not new or unique to behavioral health. When the first medical group practices emerged in Minnesota and California, they were viewed as a liberal social experiment or a form of socialized medicine by many solo practitioners (Starr, 1982). Some clinicians continue to express concerns about the potential adverse effects of managed care on the relationships between practitioners and patients (e.g., Emanuel and Dubler, 1995).

Proponents of managed care point to examples of managed care providing better coordination, better information systems and health education, and more standardization of best practices, and thus improved quality. In solo practice, it is extremely difficult to provide coordination and linkage with primary care and other practitioners. Quality management activities in managed care help to provide better matching of care with the needs of consumers and families and also reduce the number of unnecessary and ineffective procedures or visits. In addition, managed care information systems can support the collection and assessment of standardized encounter and other data to further understand what contributes to effective treatments and positive outcomes.

Medical ethicists Philip Boyle and Daniel Callahan frame the issues around managed care in the following way. Because even the vast amounts of money currently spent on health care are not sufficient to allow everyone to receive every potentially beneficial intervention, the resources must somehow be managed. Boyle and Callahan believe that a managed behavioral health care system offers more potential for quality, access, and equity than the current combination of fee-for-service and public systems of care. The argument then shifts from whether to manage care to how to manage care (Boyle and Callahan, 1993; Sabin, 1995).

PURCHASERS

Group purchasers of health care include employers, unions and associations, and federal, state, and local governments. Large private employers have been leaders in altering the buying practices in the health care market, based on their interest in increasing the value that they receive for health care spending (IOM, 1993) and in providing quality health care efficiently. Most large employers still con-

tinue the historical practice of offering substantial subsidies to their employees' health insurance premiums as part of a fringe benefits package that attracts qualified employees. Some large employers have developed their own standards for the purchase of behavioral health care (e.g., Digital Equipment Corporation), and increasingly, coalitions of employers such as the Pacific Business Group on Health are developing alliances to negotiate with health plans for standardized primary care benefits at lower prices (Brown, 1996).

|

Employers have always tried to evaluate the value of health care. To our employer groups, that is defined as a change in health status plus satisfaction, divided by cost. Catherine Brown Pacific Business Group on Health Public Workshop, May 17, 1996, Irvine, CA |

Traditionally, employers have been the main purchasers of managed care, but federal, state, and county governments have also looked to managed care to help control costs and increase the opportunity for accountability. As indicated in Table 1.2, approximately 224 million individuals are insured (as of 1995), and on behalf of these individuals, hundreds of private organizations and public agencies negotiate contracts with providers.

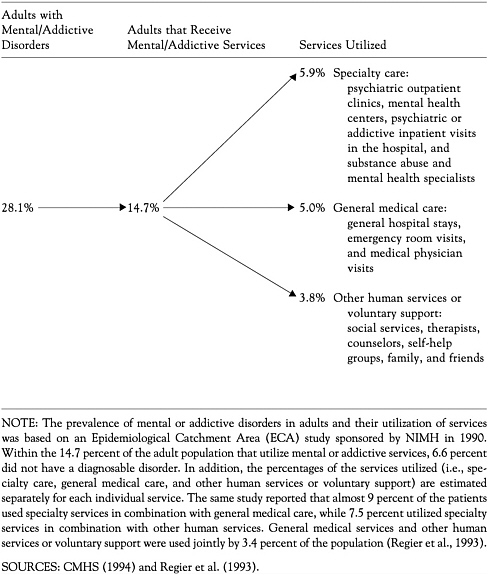

Expenditures for mental health and substance abuse treatment account for approximately 10 percent of all health care spending (Frank and McGuire, 1996). Although an estimated half of all individuals who have behavioral health problems do not receive care (see Table 1.3), the growth of spending for mental health and substance abuse treatment has been a matter of considerable concern to both private payers and state governments. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the rates of growth in behavioral health care spending substantially exceeded the rise in general health care spending (England and Vaccaro, 1991).

State governments have moved to strengthen the bargaining power of health plan buyers by encouraging the creation of purchasing alliances that enable small group purchasers of health insurance to command more choice at better prices. Twenty states have adopted measures that encourage the formation of purchasing alliances (GAO, 1994). States also have an important consumer protection role by licensing and/or certifying practitioners and provider agencies, which will be discussed later in this report (see Chapter 4). In addition, states regulate insurance plans, such as HMOs, against standards of financial solvency, benefits, and health care practice.

Purchasers can set standards of quality for the health plans and practitioners from whom they purchase care or care management, generally as part of a contract. The standards used by purchasers are highly variable and idiosyncratic across

TABLE 1.2 U.S. Health Insurance Data (in millions), 1992–1995

|

Population Description |

1992 |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

|

Total population |

251.7 |

256.9 |

259.3 |

264.3 |

|

Insured populationa |

212.8 |

215.7 |

219.6 |

223.7 |

|

HMO enrollment |

41.4 |

45.2 |

51.1 |

58.2b |

|

Specialty MBHC enrollmentc |

78.1 |

86.3 |

102.5 |

110.9 |

|

Uninsured population |

38.9 |

41.2 |

39.7 |

40.6 |

|

aHMO enrollment and Specialty managed behavioral health care (MBHC) enrollment are included in the category “Insured population” to illustrate their relative proportions. Due to potential double counting, they should not be added. b1995 projection as of June 1996. cSpecialty MBHC has been defined as an entity managing fixed behavioral health, mental health and chemical dependency treatment benefit budgets on capitated, risk-based, or performance-based contracts (Open Minds, 1996). The term excludes public programs and most provider-sponsored integrated delivery systems (Stair, 1996). SOURCES: EBRI (1996), GHAA (1996), HIAA (1996a), Open Minds (1996),and Stair (1996). |

||||

and within the public and private sectors, but the contract requirements are generally the arena in which the issues of outcomes and consumer satisfaction are addressed. In the committee's view, many new developments in these areas, such as the CMHS consumer-oriented report card, the American Managed Behavioral Healthcare Association's (AMBHA's) Performance Measures for Managed Behavioral Healthcare Programs, and state-level initiatives such as the Consumer Quality Review Teams used in Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, are likely to begin to be incorporated into contracts. For example, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) is basing its contracts on the Healthplan Employer Data Information System developed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) (HCFA, 1996).

Public and private purchasers are concerned with the cost of health care. Indeed, in the public workshops conducted by the committee, several presenters referred to cost of care as the purchasers' primary consideration. The questions for this committee are how much purchasers weigh the importance of the quality of care in their search for good value and outcomes and how purchasers can be helped to maintain and improve the quality of care as they strive for greater value and efficiency.

THE MANAGED CARE INDUSTRY

Consumers, practitioners, and third-party payers (insurance) are traditionally viewed as the main partners that interact in the delivery of health care. Man-

aged care alters the delivery of care by introducing a new control mechanism and method for formal negotiation of expected results among the stakeholders, with the expressed purpose of controlling costs through reducing unnecessary or inappropriate care. Managed care plans use a network of selected providers, which includes hospitals, residential programs, and practitioners. Managed care organizations also seek to influence the nature, quantity, and location of services that are delivered (IOM, 1996a). The contractual relationship between the purchaser

and the managed care entity and between the managed care entity and its practitioners are critical in the specification of the incentives, controls, and goals for the plan (Frank et al., 1995).

|

We know that there is competition in the health care marketplace today. I don't think anybody doubts that. But it is very much a price-driven competition. And that, we think, is very dangerous to the quality of care that patients are receiving. Margaret O'Kane National Committee for Quality Assurance Public Workshop, April 18, 1996, Washington, DC |

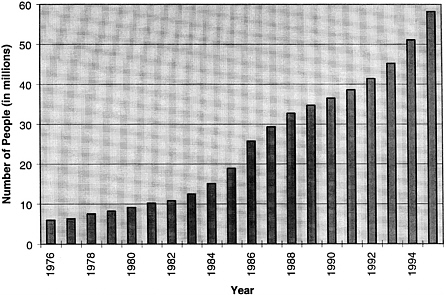

From mid-1991 through mid-1995, there was a 46 percent increase in HMO enrollment (HIAA, 1996a) (see Figure 1.1). In 1995, of the 184 million Americans with private insurance, an estimated 161 million were enrolled in some form of managed care (HIAA, 1996b). In the public sector in 1995, approximately one third of Medicaid-eligible individuals and close to 10 percent of Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in managed care plans (see Table 4.2 in Chapter 4). Growth in managed care is taking place primarily in large and medium-sized markets, and the penetration of managed care is greatest in the West, the upper Middle West, and the Northeast (IOM, 1996a).

Managed care has had a major impact on the traditional indemnity insurance industry, which was based on a system in which fees were paid for services provided. Some insurance companies, such as Prudential, Cigna, Aetna, Metropolitan Life, and Travelers, as well as the nonprofit Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans, have bought and developed their own managed care plans. During the mid- to late 1980s, the rate of growth in behavioral health care was greater than the growth in any other sector of health care. The mid-1980s also saw the emergence of a number of managed behavioral health care companies that offered to reduce the spiraling costs of behavioral health care (England and Vaccaro, 1991). A further discussion of these trends in the health care industry is presented in Chapter 2.

Another recent development in the health care industry is the increasing number of benefits consulting firms, such as Coopers and Lybrand, Ernst and Young, Hewitt Associates, KPMG Peat Marwick, McKinsey and Company, William R. Mercer, Towers Perrin, and The Wyatt Company. These companies are largely invisible to consumers and to many practitioners, but they have evolved from providing accounting and auditing services to becoming the main brokers of the managed care contracts negotiated by employers. In the past, benefits consultants worked primarily with purchasers in private industry, but with the expan-

FIGURE 1.1 Number of HMO enrollees, 1976–1995. SOURCE: HIAA (1996a).

sion of managed care into the public sector, consultants are now providing technical assistance to state agencies that want to make informed purchases and hold managed care organizations accountable for the public dollars spent.

Key stakeholders in the industry also include the private national organizations that accredit both provider agencies and managed care entities. Technically, accreditation is voluntary, but many public and private payers encourage or require that their practitioners maintain accreditation. These accreditation entities address organizational capacity, internal management and quality improvement processes, and related issues. In general, accreditation standards are evolving, and the standards for individual practitioners are better developed than the relatively new standards for managed care plans. Chapter 6 of this report discusses five of the organizations involved in accreditation for managed behavioral health care: the Rehabilitation Accreditation Commission (CARF), the Council on Accreditation of Services for Families and Children (COA), the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), NCQA, and the Utilization Review Accreditation Commission (URAC).

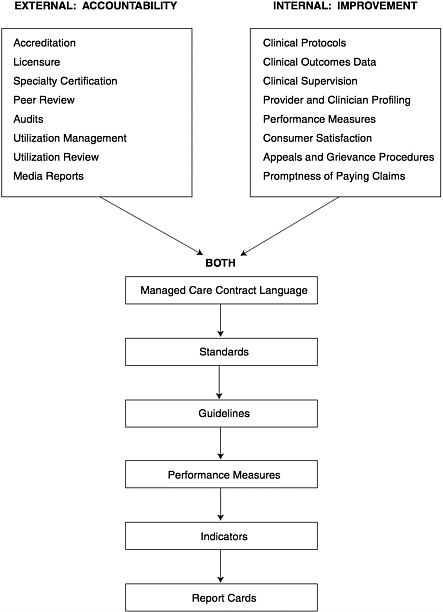

Managed care entities also carry out significant quality functions within their contracts and care networks. Examples of these functions include credentialing and recredentialing clinicians; practice guidelines; and profiles of practice patterns, outcomes, and consumer satisfaction for individual practitioners. These functions are sometimes labeled as the “black box” of managed care, because al-

though they can be powerful and valuable forces, they are handled quite differently by individual managed care organizations and networks and are not always shared with practitioners or purchasers. One goal of this report is to address this variation by developing a framework for the evaluation of quality improvement activities. Figure 1.2 presents a summary of the committee's framework for quality improvement.

STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES

The committee values the evidence-based approach to making health care decisions, and so made it a priority to review the available medical, psychosocial, and health services research on clinical outcomes. The committee also sought other empirical findings to inform the committee's deliberations, including current activities and surveys in the managed behavioral health care industry, such as those performed by AMBHA and the Institute for Behavioral Healthcare, as well as documents and reports from federal agencies such as the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, and CMHS, NIMH, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and HCFA.

The committee also reviewed descriptions of five accreditation organizations: CARF, COA, JCAHO, NCQA, and URAC. In addition, the committee reviewed the following previous reports by the IOM: Controlling Costs and Changing Patient Care? The Role of Utilization Management (1989), Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance (1990a), Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program (1990b), Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems (1990c), Treating Drug Problems (1990d), Employment and Health Benefits (1993), Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era (1996a), and Pathways of Addiction: Opportunities in Drug Abuse Research (1996b).

However, the committee also recognized that many of the study's most important questions could not be answered solely by searching the available research and health care industry literature. To provide a context for this report, the committee developed a set of principles that is based on empirical evidence, but that also relies on a consideration of issues that may not have been examined empirically. These principles are reflections of a current understanding of strategies for improving the quality of care, as well as ethical concerns that have emerged through the individual committee members' professional and personal experiences in the delivery and study of health care.

-

Helping to improve the quality of life for individuals, families, and those responsible for the legal and financial circumstances of those individuals and families should be the heart of all efforts to improve the quality of behavioral health care.

-

Because treatment is effective for mental health and substance abuse problems, it is an essential part of health care and should be accessible to all.

FIGURE 1.2 Framework for quality assessment. The figure displays a wide array of activities that can have an impact on the quality of care. Impact may vary depending on the level of responsibility for quality of care within an organization, the regulatory mechanisms that apply, the nature and extent of the relevant outcomes research base, and other factors.

-

Behavioral conditions should be viewed as clinical conditions, both in the provision of (and access to) preventive interventions and treatment and in the requirements for quality and patient satisfaction.

-

Activities to improve the quality of health care should be based on evidence of effectiveness whenever possible. Every group among the stakeholders—consumers, practitioners, purchasers, managed care companies, accreditation organizations, and other groups—must share responsibility for the quality of treatment. Commitment to improving quality should be inherent in any agreement to provide or receive care.

-

The expense of successful and appropriate treatment for mental health and substance abuse problems can be a barrier and a burden, putting individuals and families at substantial financial risk. However, untreated behavioral health problems are also costly to individuals, families, businesses, and the rest of society. Thus, providing insurance coverage against the financial risks of behavioral health problems and guaranteeing access to treatment can be justified on grounds of fairness as well as efficiency.

-

Managed care technologies offer an opportunity to increase access to preventive interventions and to control costs without imposing special limits and excessive cost-sharing. However, managed care can also bring risks of undertreatment and concerns about quality.

-

Vulnerable and disabled populations are potentially most at risk from the failures in the managed behavioral health care market. Particular attention should be paid to the impact of managed care on such populations, which include children, seniors, people from diverse cultural backgrounds, people who live in rural and other medically underserved areas, people who live in poverty, people who have developmental and other disabilities, people with co-occurring disorders (e.g., depression and alcoholism), and people who have the most severe forms of mental illness and addiction.

-

Quality improvement and accreditation are two important tools that can be used to protect and improve the quality of care. In general, quality mechanisms should be used to improve performance and reward best practices.

-

This committee adopts the definition of quality of care developed by another IOM committee: “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (IOM, 1990a, p. 21).

-

Quality of care includes several components. These include (1) a real opportunity for the person being treated to have a reasonable range of practitioners and treatment options from which to choose, and to provide informed consent (by the person being treated or by a designated representative, the approval of, and agreement with the decision or actions taken by the provider[s]); (2) the protection of confidentiality and privacy rights, balanced with the need to share clinical information to improve the coordination of care; (3) a demonstrated respect for the cultural context of the individual and community being served; and

-

(4) an emphasis on functional assessments, such as a return to work or school, as measures of success.

-

Behavioral health problems require an array of preventive and treatment services that are coordinated into a continuum of care that integrates worksites and schools with all parts of the medical treatment system, as well as with community-based services.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report has been written for a broad audience, including the stakeholders who are concerned about quality: public and private purchasers, consumers and families, the managed care industry, professional organizations, accreditation organizations, practitioners in primary care and specialty sectors, and policymakers. Health care quality is complex, and it is addressed in numerous ways: accreditation; quality assurance programs; licensure, certification, and other credentialing activities; clinical practice guidelines; consumer satisfaction; report cards; and other means.

Donabedian (1966, 1980, 1982, 1984, 1988a, b, c) has described three interrelated ways to understand and measure quality: structure, process, and outcomes. Structural measures of quality include the types of services available, the qualifications of practitioners, staffing patterns, adherence to building and other codes, and other administrative information. Process measures of quality focus on procedures and courses of treatment, such as the numbers of individuals served; on the appropriateness of the care; and on ongoing efforts to maintain quality, such as practice guidelines and continuous quality improvement activities. Outcome measures of quality include health status changes after treatment and consumer satisfaction with the care that is provided, as well as short-term or intermediate outcomes.

To prepare this report, the committee adapted Donabedian's approach to address the past, present, and likely future of health care quality improvement. Chapter 1 is intended to provide a context for the report by describing the committee's consumer protection approach to quality measurement, including the statement of principles that it used in approaching this report. Chapter 2, Trends in Managed Care, describes current influences across the spectrum of health care delivery, including quality measurement activities and the changing roles of purchasers. Chapter 3, Challenges in Delivery of Behavioral Health Care, addresses quality measurement issues unique to managed behavioral health care, including the history of separate and distinct systems of care.

Chapter 4, Structure, describes the current delivery systems for behavioral health; these include substance abuse, mental health, and primary care in both the public and private sectors, as well as separate systems for children, seniors, the military, and Native Americans. Chapter 5, Access, discusses general concerns about access, measurement of access in the private sector, and specific concerns about vulnerable and high-risk populations in the public sector. (Access is viewed

as a structural factor in the Donabedian framework, but the committee chose to consider access variables in a separate discussion.)

Chapter 6, Process, provides an overview of accreditation and quality improvement activities in their current forms. Chapter 7, Outcomes, reviews what is known from research about treatment outcomes. This chapter is supplemented by two papers in Appendix B and Appendix C: Thomas McLellan and colleagues address questions of substance abuse outcomes research, and Donald Steinwachs discusses outcomes research in mental health.

In Chapter 8, Findings and Recommendations, the committee summarizes its concerns and presents specific recommendations for future steps that should be taken to address those concerns. In developing the recommendations, the committee was mindful of the rapid rate of change in the health care system and the need to anticipate new directions and trends. The report, then, is intended to provide a general, overarching framework that shows how all of the varied current and future quality improvement activities can relate and that also may support creative and collaborative initiatives to improve the quality of care.

REFERENCES

Boyle P, Callahan D. 1993. Minds and hearts: Priorities in mental health services. Hastings Center Report Special Supplement September/October:S3-23.

Brown C. 1996. Purchasers' Perspectives on Quality. Presentation to the IOM Committee on Quality Assurance and Accreditation Guidelines for Managed Behavioral Health Care. Irvine, CA. May 17.

CMHS (Center for Mental Health Services). 1994. Mental Health, United States—1994. Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA, eds. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 94-3000. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

CMHS. 1996. Consumer-oriented Mental Health Report Card: The Final Report of the MHSIP Task Force on a Consumer-Oriented Mental Health Report Card. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services.

Donabedian A. 1966. Evaluating the quality of medical care. The Milbank Quarterly 44:166-203.

Donabedian A. 1980. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring: The Definition of Quality and Approaches to Its Assessment. Vol. 1. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press.

Donabedian A. 1982. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring: The Criteria and Standards of Quality. Vol. 2. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press.

Donabedian A. 1984. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring: The Methods and Findings of Quality Assessment and Monitoring, An Illustrated Analysis. Vol. 3. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press.

Donabedian A. 1988a. Quality assessment and assurance: Unit of purpose, diversity of means . Inquiry 25:173-192.

Donabedian A. 1988b. The quality of care: How can it be assessed? Journal of the American Medical Association 260:1743-1748.

Donabedian A. 1988c. Monitoring: The eyes and ears of healthcare. Health Progress 69:38-43.

EBRI (Employee Benefit Research Institute). 1996. EBRI Issue Brief. February.

Emanuel EJ, Dubler NN. 1995. Preserving the physician-patient relationship in the era of managed care. Journal of the American Medical Association 273(4):323-329.

England MJ, Vaccaro VA. 1991. New systems to manage mental health care. Health Affairs 10(4):129-137.

Frank, RG, McGuire TG. 1996. Introduction to the economics of mental health payment systems. In: Levin BL, Petrila J, eds. Mental Health Services: A Public Health Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

Frank RG, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP. 1995. Risk contracts in managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):50-64.

GAO (U.S. General Accounting Office). 1994. Health Reform: Purchasing Cooperatives Have an Increasing Role in Providing Access to Insurance. GAO/HEHS-94-142. Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office.

Gerstein DR, Johnson RA, Harwood HJ, Fountain D, Suter N, Malloy K. 1994. Evaluating Recovery Services: The California Drug and Alcohol Treatment Assessment (CALDATA). Fairfax, VA: Lewin-VHI and National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago.

GHAA (Group Health Association of America). 1996. 1995 National Directory of HMOs. Washington, DC: Group Health Association of America.

HCFA (Health Care Financing Administration). 1996. Growth in HCFA Programs and Health Expenditures. Baltimore, MD: Health Care Financing Administration.

HIAA (Health Insurance Association of America). 1996a. Sourcebook of Health Insurance Data, 1995. Washington, DC: Health Insurance Association of America.

HIAA. 1996b. Personal communication to the Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC. September 3.

Iglehart JK. 1996. Health policy report: Managed care and mental health. The New England Journal of Medicine 334(2):131-135.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1989. Controlling Costs and Changing Patient Care? The Role of Utilization Management. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1990a. Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1990b. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1990c. Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1990d. Treating Drug Problems. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1993. Employment and Health Benefits: A Connection at Risk. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1996a. Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1996b. Pathways of Addiction: Opportunities in Drug Abuse Research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M et al. 1994. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19.

Mechanic D, Schlesinger M, McAlpine DD. 1995. Management of mental health and substance abuse services: State of the art and early results. The Milbank Quarterly 73(1):19-55.

Miller RH, Luft HS. 1994. Managed care plan performance since 1980: A literature analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association 271(19):1512-1519.

NAADAC (National Association of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Counselors) . 1996. The Role of Alcohol and Drug Counselors in Behavioral Managed Care (Unpublished Manuscript.) Arlington, VA: National Association of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Counselors.

Open Minds. 1996. Managed Behavioral Health Market Share in the United States, 1996-1997. Gettysburg, PA: Open Minds.

Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. 1993. The de facto U.S. mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85-94.

Sabin JE. 1995. Organized psychiatry and managed care: Quality improvement or holy war? Health Affairs 14(3):32-33.

Shore MF, Beigel A. 1996. The challenges posed by managed behavioral health care. The New England Journal of Medicine 339(2):116-118.

Stair T. 1996. Personal communication to the Institute of Medicine. Open Minds. October.

Starr P. 1982. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York, NY: Basic Books.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) . 1995. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Statistics Sourcebook. Publication No. (SMA) 95-3064. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.