3

Lessons Learned

The preceding chapters defined the fundamental interests and values at stake in the governance and management of marine areas, which are constantly affected by threats, trends, and opportunities that undermine the effectiveness of traditional, fragmented, sector-by-sector governance and management systems. As a basis for recommending improvements, the committee examined a wide range of real-world situations, three of them in-depth (as case studies) and seven in less detail. This chapter summarizes lessons learned from these investigations, especially in terms of the organizational and behavioral aspects of governance and management systems and the tools necessary for effective management.

CASE STUDIES

The committee conducted in-depth examinations of three representative examples of marine governance and management processes and structures in situations where problems have been especially difficult to resolve: (1) the designation of marine sanctuaries and parks, (2) the resolution of multiple-use conflicts, and (3) fisheries management. Case studies were conducted by the Center for the Economy and the Environment of the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) and the Marine Policy Center of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) with oversight by the committee. (The complete case studies are available from the Marine Board.) The case studies focused on the following geographic areas:

-

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (NAPA)

-

Southern California coast (offshore and coastal region from the San Luis

-

Obispo/Monterey County Line in the north to the U.S./Mexico border in the south) (NAPA)

-

Gulf of Maine/Massachusetts Bay (WHOI)

In each of the case studies, an activity or issue of local importance was examined to reveal the success or failure of existing management and governance structures and processes. Although other concerns might also have been of interest to this study, the committee limited its focus to the core problems, use conflicts, fragmented decision making and management, and lost opportunities and economic benefits: offshore oil and gas leasing and production in the southern California case, fisheries management issues in the Gulf of Maine study, and problems of regional marine and coastal planning in the Florida Keys case.

The committee attempted to determine whether present systems succeeded or failed in managing conflicts, exercising stewardship by protecting the resource base and the broader environment, and realizing the potential economic benefits of appropriate resource development. The following questions were central to each case study:

-

Were issues of long-term national interest identified and addressed?

-

What was the role of intergovernmental (i.e., local, state, and federal) relations?

-

To what extent were these characterized by coherence or fragmentation, cooperation or conflict?

-

What was the nature of the institutions involved?

-

What kinds of behavior (cooperative or adversarial, hierarchical or collaborative) characterized them?

-

What kinds of conflict management were used (litigation, stalemate, compromise, partnership)?

-

Were institutions flexible enough to evolve to meet changing needs or changing perceptions?

-

Were environmental and economic goals appropriate?

-

Were these goals achieved?

-

What was the range of factors that entered into decision making?

-

What was the range of stakeholder involvement in decision making?

Criteria for Conducting and Analyzing the Case Studies

In addition to the relatively open-ended questions listed above, the committee outlined the characteristics of successful governance systems. These characteristics are drawn from the background paper for the study (Appendix B), issue papers prepared by several committee members at the start of the project, and experience with coastal governance and management. The principles are defined in Chapter 1.

The following sections summarize the examples the committee examined, identify themes that appear in all or most of them, and compare these themes to the governance criteria listed above. To facilitate their evaluation, the committee summarized the examples in terms of:

-

why each was considered a success (or failure)

-

characteristics of the governing process

-

enabling factors or prerequisites that set the stage for success (or failure)

Although the examples differ widely in terms of scale, scope, and time frame, they all reflect attempts to address the core governance problems of use-conflicts, fragmented decision making and management, and lost opportunities and economic benefits.

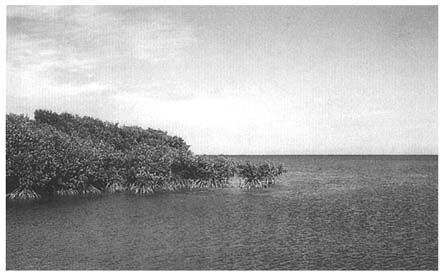

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

The Florida Keys are a unique chain of islands extending south and west from the tip of the Florida peninsula. The reef (the only living coral reef in the continental United States) and the flats surrounding the Keys are home to a large number of marine species. The Keys are heavily used for tourism and commercial and recreational fishing, are adjacent to marine transport routes between the U.S. mainland and Latin America and the Caribbean, and are close to areas being considered for oil and gas exploration. The natural systems of the Keys may be affected not only by activities in the Keys themselves (e.g., diving, treasure salvage, development), but also by the ecological problems of the adjacent Florida Bay. In 1990, in recognition of the environmental value of the Keys and apparent threats to their health, Congress declared the Keys a NMS and directed NOAA to complete a sanctuary management plan to protect them.

This plan is far more extensive than plans for other marine sanctuaries. It covers the entire Florida Keys and adjacent waters and details responsibilities for 18 federal and state agencies and departments, as well as for local governments and nongovernmental organizations. The plan is a comprehensive analysis of threats to the environment in the Keys and proposes more than 90 specific strategies to address these threats. It sets priorities, commits agencies to monitoring programs, and defines research for updating and adjusting the plan (NOAA, 1996).

Despite the success of the planning effort, NOAA will face significant challenges in the future. The Core Group that wrote the plan has been dissolved, even though success depends on a continuous planning process in the Keys. NOAA must make decisions about the composition and role of the Advisory Council and other planning bodies. Upcoming decisions about major issues (e.g., controlling the impact of water quality) depend on NOAA's ability to sponsor or conduct high-quality scientific research to resolve uncertainties about how the Keys ecosystem functions.

Mangrove Forest, Key Largo, Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Photo courtesy of William Eichbaum.

Reasons for success or failure: After the final sanctuary management plan was issued (NOAA, 1996), a local referendum in Florida on the future of the sanctuary was held in November 1996. The result was 55 percent to 45 percent against the plan. Although the referendum was only advisory and NOAA plans to continue implementing the plan, the long-term outcome is not yet clear.1 The management plan is at the cutting edge of widely discussed theories about how to move from narrow, single-purpose management systems to ''community-based" environmental management systems.

In pursuit of its ambitious goals, the plan achieved some notable preliminary successes. The plan represents the first comprehensive effort to identify and assess the complex operation of the natural system of the Keys. The planning process was based on collaborative decision making, which required extensive interaction and cooperation among federal, state, and local agencies, as well as a range of nongovernmental constituencies. An important component in the collaborative process was the Sanctuary Advisory Council, and innovative group that included representatives of a wide range of local stakeholders. Unfortunately, the start-up of the council was delayed for several months for administrative reasons, and its

role was not clearly defined. Nevertheless, despite, or perhaps because of this, the council eventually played a central role in the planning process.

Between July 1993 and March 1995, the plan disappeared from public view while details were negotiated and interagency reviews were completed. This lengthy delay resulted in a loss of momentum, and by the time the plan was finally published, opposition had been mobilized. In spite of the length of time spent preparing the plan (68 months), uncertainties and suspicions about NOAA's authority and intentions generated intense conflict.

The plan has yielded some benefits, however. New rules and better enforcement now protect the reef. Scientific uncertainties about the causes of water quality problems have been addressed. Elements of the plan have appeared in the county's recent land use plan, and data generated in the planning process have been used by state agencies to make decisions affecting the Keys. The structured planning process has been able to overcome fragmentation. Important elements of the planning process were a consistent core group of knowledgeable decision makers, partnerships with nongovernmental agencies, and a broad-based advisory council. It remains to be seen how effective this collaborative effort will be in overcoming conflicts among supporters and opponents of the sanctuary.

Key features: Influential legislators led the efforts to designate the sanctuary, and the legislation they helped enact went beyond previous legislation in important ways. It required NOAA to consider the full range of environmental issues and to create an advisory council. It required the EPA to work with the state to conduct research into the causes of water quality problems. Finally, it directed that zoning be considered to restrict certain activities. These broad mandates prompted NOAA to involve professional planners from its Strategic Environmental Assessment Division in the planning process. They facilitated activities of the core group, which included representatives of federal, state, and local agencies. Both the core group and the advisory council were new kinds of organizations within the sanctuary program, and NOAA had to learn through experience how to coordinate their activities.

The plan was developed in the context of a long history of struggle between county and state governments over land use in the Florida Keys. Environmental issues and whether or not to impose controls on development are central to local politics. Not surprisingly, the draft management plan provoked intense controversy over the specifics, especially zoning, and over the power of the federal agency (NOAA) in general.

Enabling factors: There was general consensus among stakeholders that the Florida Keys are unique and that everyone had an interest in preserving the unique character of the area, despite disagreements about how the Keys should be managed. The legislation itself was extremely broad, compelling NOAA to take novel approaches to sanctuary planning. These approaches were supported by NOAA's preexisting relationships with state agencies and by the existence of two smaller

sanctuaries in the Keys. Shortly after the legislation was passed, NOAA officials and the governor's office agreed to work cooperatively and informally to develop the management plan. The manager of Looe Key NMS became the manager of the entire Florida Keys NMS, and his network of relationships, his personal style, and his ability to foster communication and collaboration were important elements in the planning process.

The core group and the advisory council adopted different approaches to decision making. The core group was much more formal and organized than the advisory council, which was more informal and people-oriented. As a result, problems and constituencies were approached in a variety of ways, which increased the chances of success. Finally, Florida has much more authority to intercede in local land use decisions than many other states. Thus, the state was able to use the results of the sanctuary planning process to make management decisions to protect the environment of the Keys.

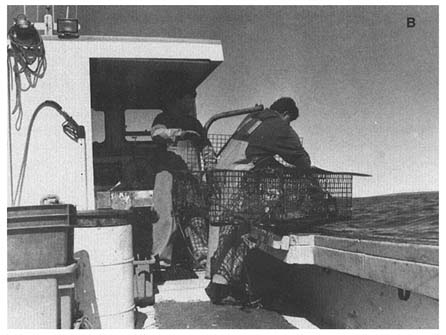

Southern California Outer Coastal Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing

Oil development in the Santa Barbara Channel, northwest of Los Angeles, has a long history. The nation's first offshore oil well was drilled in this area in 1898 from a pier extending from shore. Santa Barbara County passed moratoria on offshore wells as early as 1927. Recent governance efforts must, therefore, be seen in the context of a long-standing conflict between constituencies for whom resource extraction is paramount and constituencies for whom conservation is

Oil and Gas Platform located offshore, Carpinteria, California. Photo courtesy of the Minerals Management Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

paramount. In the last 20 years, there have also been rapid changes in the governance system for marine areas in California. During this period, California's Coastal Act was enacted, and consistency review (to promote consistency between state and federal policies as required by the CZMA) was extended to the state. During this same period, local, regional, and state authorities enacted increasingly strict controls on air pollution from a wide range of sources, ultimately including activities on the OCS. At the same time, federal agencies, such as MMS, have tried to develop more flexible policies that are responsive to local circumstances and to streamline their decision making. MMS' efforts to adapt to the changing circumstances in southern California has resulted in the creation of novel collaborative processes, the resolution of several long-term disputes, and an increase in oil production.

Against this background, Exxon installed three offshore oil and gas drilling platforms in the Santa Ynez unit, the first in 1976 and two more between 1989 and 1992. In addition, Exxon's on-shore processing plant at Las Flores Canyon began operation in 1993.

Reasons for success or failure: In response to demands that local and state governments play a larger role in making decisions that affected them, the MMS learned to share authority with communities and governments. The policies adopted by MMS, the state, the counties, and the oil companies as a result reduced overt conflict and friction and increased the system's ability to adjust to changing conditions. Permitting processes were streamlined, and an integrated regional planning approach was adopted. This approach, in turn, produced better environmental reviews to support decision making and fostered more productive, long-term working relationships among the parties. Significant agreements were negotiated regarding air pollution and oil transportation and processing, which resulted in the licensing of additional facilities and increased production and a net improvement in regional air quality.

A significant indicator of success was a recent statement by the Santa Barbara County Board of Supervisors that, with the proper safeguards, they might consider allowing additional leasing in the region. However, federal restrictions on the involvement of nonfederal employees in contracting decisions resulted in lengthy delays and eventually undermined trust in federal responsiveness to local requirements.

Key features: Historically, local opposition to oil development has been strong. Santa Barbara County had passed moratoria on offshore wells as early as 1927 for aesthetic reasons. It is no surprise that more recent development provoked intense political battles over air pollution, facility siting/licensing, and transportation. For example, in 1976, Exxon responded to local attempts to control air pollution from OCS activities by anchoring an offshore storage and treatment facility just beyond the area of state and local jurisdiction, in federal waters, an act that was seen by many local stakeholders as arrogant disregard for state

and local concerns. At the time, neither the state nor the county had jurisdiction or leverage over OCS activities, and officials at each level of government came to see the facility as a highly visible symbol of governance problems relating to oil and gas development.

In this context, MMS, realizing that changes had to be made to come to grips with regional and local conditions, loosened the links between management policies in the Gulf of Mexico and in California. MMS also agreed to share significant authority with other parties, resulting in the creation of well defined, collaborative, decision-making mechanisms. This led, for example, to the establishment of joint review panels, which produced a single document that satisfied a variety of federal and state environmental requirements. MMS officials now regard the joint review panels as part of their new way of doing business.

Over a period of years from the late 1970s through the 1980s, Exxon proposed a variety of development scenarios, including offshore and onshore pipelines, a marine terminal, using shuttle tankers to deliver oil, the offshore storage and treatment facility, and an onshore processing plant. This range of options opened several doors for negotiation among local, state, and federal agencies. At critical junctures, both Exxon and Santa Barbara County turned to allies in the federal government for support; however, their inability to win a clear victory at the federal level forced them to return to the regional negotiating arena.

By the end of 1985, all of the parties (county, state, Exxon, Department of the Interior) were entangled in lawsuits about air quality, oil transportation, and future development. Without necessarily conceding their major points, the parties negotiated a series of agreements that resolved these issues and set the stage for building additional platforms and an onshore processing facility. Once the long-standing issues were out of the way, MMS, the county, and the oil companies in 1993 initiated a study to address the issue of phasing in future development. MMS' efforts in southern California thus represent a significant break with its traditional way of treating OCS development without the involvement of local coastal communities.

Enabling factors: The blowout and oil spill of 1969 sensitized local residents and governments to the possible consequences of oil development and aroused fierce opposition to further development. The 1976 amendments to the CZMA gave the state the power to review federal actions in the OCS for consistency with the state's coastal plan. The importance of air pollution in southern California provided state and local agencies with additional leverage over offshore development, particularly after the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 gave EPA control, which EPA delegated to the county Air Pollution Control District. A series of moratoria on the sale of OCS leases, beginning in 1982, added to oil company incentives to increase production on the leases they already held.

In this environment, a new MMS regional administrator was appointed who recognized that local residents and governments had to be included in decision

making. His personality and character traits were vitally important in establishing and maintaining relationships among the parties. In addition, the new administrator initiated and/or agreed to specific policies, including collaborative power-sharing processes, conflict resolution training for MMS staff, and moving the office from Los Angeles to Ventura County, all of which contributed to a useful framework for problem solving. This flexibility was supported by MMS headquarters, which allowed the local office considerable latitude. Finally, after a long history of conflict, most participants had come to believe that collaboration is better than fighting each other in the courts.

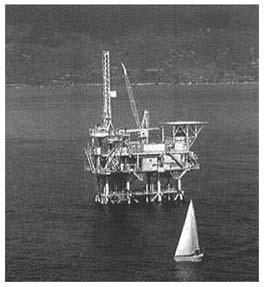

Gulf of Maine Fisheries

The Gulf of Maine is the largest semi-enclosed shelf sea bordering the continental United States (Christensen et al., 1992) and includes almost every conceivable use of the marine environment. The gulf watershed extends from Nova Scotia and the Bay of Fundy in the northeast to Boston and Cape Cod in the southwest. Nearly one-third of the gulf's relatively sparsely populated coastline is estuarine habitat. The area offshore, notably on Georges Bank, over the western Nova

Stern of gillnetter boat with crewman dressing groundfish off the coast of Massachusetts. Reprinted with permission from Commercial Fisheries News, copyright Compass Publications, Inc. Photograph by Richard Burnham.

Scotia shelf, and in the Bay of Fundy, has been extremely productive and historically rich in lobster, scallops, groundfish, and other stocks.

Because of the low population density and the small amount of river runoff (and hence small pollutant loads), the marine waters of the Gulf of Maine do not show the serious signs of environmental degradation typical of more urbanized regions (Waterman, 1995). However, cumulative detrimental impacts on habitats and on the living marine resources are evident in many harbors and estuaries throughout the Gulf of Maine (NRC, 1995c). In particular, intensive harvesting of groundfish stocks, especially cod, haddock, and yellowtail flounder, has led to severe declines in these species. Most of the commercially important stocks have fallen below or are approaching the lowest estimated levels on record. Two stocks, the Gulf of Maine haddock and the Georges Bank yellowtail flounder, have been declared commercially extinct (NRDC, 1997). The overall levels of groundfish are extremely low, as is the estimated spawning biomass for these species. Chemical contamination of fishery resources has led to several fishery advisories or closures (Capuzzo, 1995).

Stock declines have resulted in substantial economic losses and the social disruption of fishing communities. The New England Fishery Management Council has closed fisheries and issued moratoria in an attempt to rebuild stocks, and both federal and state governments have implemented various support plans to lessen economic impacts, but the future of the offshore fishing industry in this region is still in doubt.

Reasons for success or failure: New England groundfish stocks are in a state of collapse. There is widespread agreement among the scientific community that this collapse was caused by overfishing (Hoagland et al., 1996). As Murawski (1996) summarizes:

Groundfish…have not fared well under domestic management.…The rapid increase in fishing effort during the late 1970s and early 1980s resulted in increased fishing mortality rates.…In recent years, fishing mortality rates have exceeded recruitment overfishing levels by a factor of 2 or more.…The recent decline in these offshore resources is attributable to persistent, gross recruitment overfishing…declines in stock sizes and landings could have been averted or at least mitigated if the stocks had not been significantly recruitment overfished.

Key features: Offshore fisheries in the Gulf of Maine are managed under the provisions of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (FCMA) of 1976. This law was passed largely in response to concerns that foreign fleets were depleting fish stocks located near the United States. In fact, New England fishermen sailed up the Potomac to Washington, D.C., in 1974 to protest the impacts of foreign fleets. The New England Fishery Management Council, under the FCMA, manages fisheries in the Gulf of Maine and includes voting representatives of the fishing industry, the NMFS, and coastal states in the region. The council is responsible for enacting fishery management plans for each fishery

in its jurisdiction in accordance with the statutory principles of the act. These include preventing overfishing while maintaining optimum yield, basing decisions on the best scientific information available, and promoting efficiency in the utilization of fishery resources.

Before 1971, restrictions on mesh size were the preferred approach to prevent overfishing under an international management regime. Beginning in 1971, total allowable catches were set on the major groundfish species; in 1974, quotas for each fishing nation were established. Since 1976, the New England council has implemented a variety of management regimes in attempting to meet these goals. In general, the management systems have oscillated between input and output controls. Input controls include gear restrictions (e.g., minimum mesh size for trawl nets) or the prohibition of specific technologies. Output controls, such as total allowable catches (TACs), limit the number of fish that can be harvested. By 1982, because fish populations had not recovered, the quota-based system was replaced with a system of input controls: minimum mesh sizes and minimum fish sizes. These were tightened periodically until 1994, when the council placed a moratorium on new entrants to the fishery, limited the number of allowable days at sea, and restricted the extent of fishing (Amendment 7). Finally, an amendment to the fishery management plan adopted in 1996 established a TAC that, when exceeded, triggers further restrictions.

Enabling factors: The various shifts in the management regime were attempts to respond to problems that arose during each previous regime. Thus, individual nation quotas were adopted in 1974 after the haddock stock had collapsed from pulse-fishing with small mesh nets by the Soviet trawler fleet in the 1960s. However, quotas led to "derby" behavior (also called the "race for fish"), causing the fishery to be closed down earlier each year as more vessels entered the open-access fishery. This system was later modified to limit the catch on individual trips, but it was impossible to monitor daily landings of all vessels. Catches were often mislabeled and/or landed illegally, false fishing locations were reported, and other forms of noncompliance increased. The stock recovery in the 1970s prompted a return to gear-based (or input) regulation in 1982. However, the open-access fishery and the lack of an effective TAC program contributed to another cycle of severe overfishing. This is an example of a phenomenon described as "the solution becomes the problem" (Checkland 1982; Clemson 1984).

Other factors were also significant in this management history. When the FCMA was passed in 1976, the New England fishing fleet was composed predominantly of small, old vessels that concentrated mainly on near-shore fishing. The open-access policies of that period, combined with ample federal subsidies and support programs, provided substantial incentives for fleets to expand, which ultimately led to overcapacity. In addition, the New England council had difficulty developing applying an operational definition of overfishing. Although regulatory guidelines mandated the development of a definition, the council was

not given a specific deadline. This allowed disagreements to persist within the council about the status of individual stocks and delayed consensus about overfishing and the implementation of a stock rebuilding program. Finally, the Conservation Law Foundation brought suit against NMFS, and deadlines were established as part of the consent decree settling the suit.

The governance regime was unable to resolve the fundamental tension among the FCMA's statutory goals, which called for stock conservation, optimal yields, and economic efficiency. As a result, valid scientific warnings of imminent stock collapses were not acted on. NMFS and the council were subject to political pressure by interest groups acting outside of the formal governance structure (the "end run" phenomenon).

Alaska Fisheries By-Catch2

In the fall of 1995, the Alaska Fisheries Development Foundation, with funding from NMFS, conducted a series of workshops in Alaska to explore solutions to by-catch problems in a wide range of commercial fisheries. Workshop participants included key decision makers in the industry, including the heads of major professional and industry associations, executives of large fishing firms and fish processing companies, government fisheries scientists, representatives of Native American groups, the director of the regional fisheries management council, and the local representative of an international environmental organization.

Reasons for success or failure: Although the workshops did not result in the implementation of solutions, they represented a notable break with the past. They provided tangible evidence of the opportunity for and the benefits of collaborative problem solving. By starting to bridge gaps not only between regulators and the fishing industry but also among different groups within the fishing industry, the workshops raised hopes that by-catch problems could be addressed locally.

Many of the participants remarked that this was the first time they had met to discuss common problems outside the formally regulated (and often divisive and competitive) stock allocation process. In this new forum for problem solving, participants found common ground they had not previously been aware of, regulators received valuable feedback about impediments to problem solving, and novel solutions were proposed and discussed from a wide range of viewpoints. Participants came away with tangible experience of constructive cooperation. However, because no permanent infrastructure was established for collaborative decision making, no further progress on resolving by-catch problems has been made.

Key features: The workshops were characterized by collaboration, active participation by key decision makers, and a format that established equality among

all participants. The workshops were place-based in that they focused on a geographically defined area. They constituted a new forum outside traditional decision-making process.

Enabling factors: The severe conflicts in the past had demonstrated the potential dangers of noncooperation. Growing awareness of the potential repercussions of continuing by-catch problems provided an additional impetus to cooperation. Frustrations that local problem-solving was stymied by the existing regulatory structure had been building. Hands-off funding support from the NMFS was the catalyst for change, and allowing local decision makers to develop their own ideas, facilitated by uninvolved outsiders, created new channels of communication.

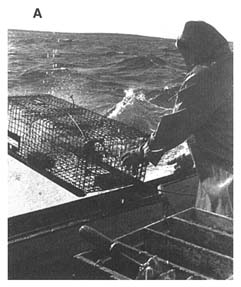

Maine Lobster Fishery

Throughout its history, the seasonal Maine lobster fishery has been dominated by independent fishermen using boats under 36 feet in length. Until recently, the catch was effectively (though indirectly) controlled by the inefficiencies of wooden traps and limitations on navigational technology, sounding gear, and boat speed and size. The number of fishermen was also limited because the rules required that fishermen live close to the area they fished, encouraging a sense of stewardship among fishermen, who identified personally with specific areas. At the same time, it allowed fishermen a level of control over who fished and how lobsters were harvested.

Recently, new technology has upset these relationships. More rugged and efficient wire traps, larger and faster boats, and more sophisticated navigational gear have enabled fishermen to fish much larger areas and to fish them much more intensively. As a result, both the number of fisherman and the size of the catch have increased rapidly in the past decade. To control expansion and limit damage to lobster stocks, the state of Maine passed fishermen-supported legislation to create a democratic, bottom-up management process focused around local fishery councils. This process incorporates controls (i.e., limits on the number of traps per boat) and an apprenticeship plan to limit access to the fishing grounds.

Reasons for success or failure: This plan appears to have the potential to prevent the overuse of resources and promote sustainability. It has provided a democratic mechanism for resolving conflicts and implementing solutions to access and enforcement issues. However, the plan does not explicitly take into account scientific knowledge about the dynamics of the lobster population. In addition, it is too early to tell if the plan will be successful (it has only been in place since mid-1996).

Key features: The overuse of resources has been avoided by protecting both juveniles and the older brood by imposing size limits and by removing egg-

bearing adults from the harvest by requiring that they be marked when caught. These conservation measures have been retained, at the insistence of the fishermen, despite efforts by the state legislature to remove them. Fishermen are protected from excessive or destructive competition by limitations on the number and size of traps per boat. Even though a statewide limit was established by the legislature, local management councils have the option of voting to establish lower limits as well as modifying or establishing other controls in each district. An apprenticeship program limits fishermen to those who have completed a two-year training program, thus mitigating the ''open-access" problem that contributed to the decline of the offshore groundfish stocks in the Gulf of Marine. Controlling both technology and the size of the harvesting unit (trap limits) rewards skill and encourages local efforts to husband wild stocks. This structure is based on the delegation by NMFS of certain management authority to the state, and then by the state to local, democratic management councils, whose conduct reflects their local self-interest in maintaining a healthy stock.

Enabling factors: There was widespread recognition among fishermen that more advanced technology and lower barriers to entry constituted a serious threat to the fishery. In a series of opinion surveys, more than 85 percent of fishermen expressed a desire for trap limits. There was a strong tradition of local resource control and decision making, and the state was committed to a collaborative approach as the basis for improving the management regime. Not only was NMFS willing to share power with the state, but the state was also willing to share power with local management bodies. Finally, there was a sufficient base of scientific knowledge, as well as a desire to improve the relationship between the scientific and fishing communities.

Chesapeake Bay Program

Efforts to restore and protect Chesapeake Bay began in the late 1970s when legislation directed the EPA to carry out a study of the problems of the bay and recommend solutions (Eichbaum, 1984). The study was jointly directed by EPA and the states of Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and the District of Columbia and involved many scientists who had studied the region. The study produced integrated recommendations for strategies to correct the problems of the bay. These recommendations covered a wide range of issues, including point and nonpoint source pollution, monitoring and evaluation, and future management structures. The several states embraced most of the recommendations and added suggestions for land development practices and resource management to address problems associated with oysters and striped bass (U.S. Department of Natural Resources, 1995).

Beginning in 1984, each state, the District of Columbia, and the federal government began to develop and implement programs to restore the Chesapeake

Striped bass restored in Chesapeake Bay after strict management regime. Photo courtesy of William Eichbaum.

Bay. A unique aspect of this management program was the joint system of governance, which was created voluntarily by the several jurisdictions. The essence of this system was an executive council that included the state governors, the mayor of the District of Columbia, and the EPA administrator. Under the executive council, a management committee was given more routine responsibilities for overseeing the implementation of specific programs. Working committees ensured that proper attention was given to specific issues, such as monitoring and resource management. This structure was duplicated in parallel scientific and citizen advisory committees.

Reasons for success of failure: The model developed for restoring the Chesapeake Bay has proven to be very successful. It has been a resilient vehicle for more than a decade of regional management of the bay and has served as a model for estuary governance across the nation. The success is attributable, in large part, to the political leadership that has been exercised from time to time by various members of the executive council.

Key features: The intimate involvement of regional scientific experts, interested citizens, and other economic stakeholders has been important to success. Participation was voluntary, and the structure was tailored to the technical as well as political traditions of the bay region. An important element of political

accountability has been an intensive monitoring program, which allows all interested parties to track accomplishments. In addition, the executive council has provided a public platform for making bold commitments to good governance, such as the 1987 decision to reduce the discharge of nutrients into the bay by 40 percent (EPA, 1995).

Enabling factors: This governance structure was possible because political leaders responded to a dramatic threat to a highly valued resource. There were no appropriate models for voluntary approaches to governing such a large region or such a complex set of issues, so the situation required experimentation in the context of political commitment. However, as time passes and some indicators of successful restoration appear, it is becoming less certain that this voluntary system will continue to work as effectively, especially for the jurisdictions with the least to gain from protecting the bay.

Long Island Sound National Estuary Program

Long Island Sound is one of the country's most urbanized estuaries. In the late 1980s, despite improved wastewater treatment in the New York metropolitan area and Connecticut, water quality in the sound deteriorated. Particularly notable was extreme hypoxia (low dissolved oxygen) during the summer months. In an effort to address these problems, Long Island Sound was designated for inclusion in the NEP (National Estuary Program) in 1989.

The NEP planning process involved extensive analysis of the water quality, including the development of a complex computerized model of water circulation within the sound. These studies revealed that the primary water quality problem was an excess of nitrogen, which stimulated algae blooms that subsequently died and created the low oxygen level. The Policy Committee of the NEP, including representatives of the states of New York and Connecticut, adopted a "no net increase of nitrogen" policy for wastewater discharges from the two states.

This policy was administered on a regional basis, requiring that treatment plants work cooperatively. Treatment innovation at the local level was necessary to meet the overall performance standards for dischargers. There have already been significant reductions in nitrogen levels in both states, and more are expected. The final CCMP (Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan) for the NEP used the computer model to refine nitrogen reduction targets by revealing where the greatest environment benefits could be achieved at the lowest cost.

Reasons for success or failure: Real reductions in nitrogen loadings have been made and are expected to continue. Support for the plan to improve water quality in the sound is widespread. A means has been established for making the most cost-effective investments first and then for evaluating the results before deciding on further, more costly, reductions.

Key features: A commitment was made both to broaden public participation in decision making and to evaluate key problems scientifically. The "no net increase" in nitrogen policy and the subsequent CCMP focus on results and allowed individual treatment plants, local governments, and states to find technical solutions that fit their needs. The freedom to innovate to achieve stated goals was a central feature of this program.

Enabling factors: Funding was sufficient to complete the computer model, which was an essential evaluation tool. Combined with other scientific information, this model provided a basis for decision making. The working relationship between the states and EPA was excellent, and constituent groups provided strong support for positive action by the NEP Policy Committee.

Oregon Rocky Shore

Oregon established a planning program for ocean resources in 1987 in response to federal proposals for offshore oil and gas and marine mineral exploration. The legislature amended the program in 1991 to create an Ocean Policy Advisory Council in the Office of the Governor, staffed by the Oregon Coastal Management Program (CMP). The council's initial focus was on the degradation of rocky shore habitats caused by variety of human activities.

A strategy was developed with an ecosystem-management approach involving all relevant state and federal agencies as well as the public. The strategy was supported by information from a site inventory by state and federal resources agencies through a special four-year grant from NOAA to enhance the Oregon CMP. The Rocky Shores Strategy, now part of the Oregon Territorial Sea Plan adopted as part of the Oregon CMP, contains overall goals and policies and addresses the natural resources and management issues of each site, including rocky cliffs, rocky intertidal sites and associated submerged rocks and reefs, and off-shore rocks and reefs. The management strategy was accompanied by a campaign to increase public awareness and foster a sense of stewardship of rocky shore resources. Several state agencies have begun to implement the strategy through a combination of regulations, on-site programs, additional planning, and work with local volunteer groups.

Reasons for success or failure: The rocky shores strategy has provided the first-ever comprehensive assessment and management plan for all rocky shores in the state. It has focused the attention of two key state agencies on the many issues confronting management of Oregon's rocky shores and has provided a framework for resolving the most serious conflicts between resource use and resource conservation. The program is successful because it is based on sound information, involves all relevant agencies, responds to site-specific situations but within an ecosystem context, and involves the public.

Key Features: A detailed rocky shores inventory and resource analysis was conducted over a period of two years by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the University of Oregon Institute of Marine Biology. Additional resource inventories and site surveys were conducted on offshore kelp reef areas. An open planning process allowed various interested parties to help fashion the goals, policies, and site-management prescriptions and gave a much wider than usual range of stakeholders a voice in the outcome of the planning process. A communications strategy, linked directly to overall goals and objectives, as well as to needs or opportunities of each site, was developed by an interagency group and is now being implemented at selected sites.

Enabling Factors: Public support was crucial to this project. In fact, a series of public workshops and listening sessions at the beginning of the planning process revealed a high level of public concern about the degradation of rocky shores. Funding from NOAA enabled the state to acquire necessary inventories and to perform analyses so that specific management prescriptions could be fashioned to meet on-site needs. The existence of the program, with its own clear policies and coordinated means of enacting them, enabled the state to play a strong role in determining the rules of engagement with federal ocean resource agencies. As a result, state managers were able to ensure that the program was as responsive as possible to local needs and circumstances. The evident effectiveness of the strategy led several key state and federal agencies to embrace it as a means of resolving long-standing management problems.

San Francisco Bay Demonstration Project

The San Francisco Bay Demonstration Project represents one of several attempts by NOAA's National Ocean Service (NOS) to develop new ways of refining its products and services, more effective ways of targeting local and regional needs, and to improve the efficiency of its operations. In San Francisco, NOS attempted to find ways to package its technical services and data to support shipping, port management, and coastal resource management. It did so in large part through a series of discussions with local agencies and groups to identify key local issues and information needs. The staff of the San Francisco Bay Demonstration Project then worked with these groups to find ways to repackage the data NOS gathers to meet local needs.

Reasons for success or failure: The San Francisco Bay Demonstration Project focused on providing tangible help for meeting specific needs, mostly by finding ways to overcome information fragmentation and the absence of data in these areas, thereby enhancing opportunities for realizing economic benefits from coastal resources. For example, more accurate and readily available bathymetry, navigation tools, and water level information made it possible for the Port of

Cargo-handling facilities, Port of Oakland, California. Photo courtesy of William Eichbaum.

Oakland and shipping companies to operate more efficiently by increasing the effective depth of existing navigation channels. By acting as a service agency, and by emphasizing cooperative solutions, NOS helped build new working relationships among agencies in the region. Future conflicts over competing uses may be reduced by making better information more readily available to stakeholders.

Key features: The project reached out to local stakeholders to identify local issues and needs and focused on building relationships rather than on dictating solutions. Potential solutions were defined through a collaborative process that emphasized local involvement. The project had a clearly defined overall goal of making better use of available scientific information and was clearly place-based since it identified San Francisco Bay as its service area.

Enabling factors: The San Francisco Bay Project was a conscious attempt by a federal agency to play a new role. The attempt was supported by a clearly stated policy to that effect. Success in fulfilling this role largely depends on the ability of NOS's local representatives to improvise and behave opportunistically by establishing relationships wherever local agencies are receptive to the idea rather than by attempting to follow a rigidly prescribed plan. The fact that NOS had

valuable information increased the chances of success. Finally, the NOS site manager had the necessary negotiating, marketing, and leadership skills to get the job done.

Santa Monica Bay Restoration Project Regional Monitoring

The Santa Monica Bay Restoration Project (SMBRP) is a part of the EPA's NEP. Its primary charge is to develop and implement a regional management plan to protect and restore resources in the region. Working in close association with a regional regulatory agency (the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board) and through a series of committees with broad stakeholder participation, the SMBRP developed a Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan to provide regionally integrated information about compliance, risks to human health, the status of regional resources, and the success of restoration. The SMBRP held a series of planning workshops to prioritize issues and establish ground rules for revising existing monitoring programs. The SMBRP then empaneled a series of working groups to draft and implement revisions to the monitoring program.

Reason for success or failure: The working groups created regionally integrated programs from existing fragmented monitoring programs without raising costs and targeted these revised programs to meet the information needs of specific decision makers. As a result, these programs adopted different strategies (e.g., day-to-day empirical health management, more formal longer-term risk assessment) appropriate to different issues. By focusing rigorously on how monitoring information would be used, the work groups used the program design process to streamline decision-making relationships at the agency level, clarify policy, and reduce conflicts among stakeholders. The revised programs standardized assumptions and methods and specified information flow. Because all key stakeholders participated, the working groups strengthened cooperative relationships among agencies.

Key features: The NEP provided long-term goals that were clear enough to focus efforts but flexible enough to accommodate local and regional variations. Thus the NEP furnished leadership and guidance without exercising undue control. The Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board also adopted a new role. They set boundary conditions and facilitated and managed the process rather than mandating solutions. The working groups followed ground rules developed in previous planning steps. These included an implicit cap on costs, a commitment to collaborative and consensus-based decision making, an understanding that program revisions had to be based on sound science, and a focus on improving coordination. All relevant stakeholders were included, even if they had not historically been involved in compliance monitoring programs. Positive momentum was created and maintained by incrementally implementing revisions to

existing programs as soon as they were agreed on by all participants. Shared decision making validated each participant's interest, and the geographical boundaries of the project helped maintain a common focus.

Enabling factors: Pre-existing and long-term professional and personal relationships among many of the stakeholders contributed to the feeling of trust and the sense that the SMBRP's activities were, in part, a continuation of past work. As a result of this shared history, there was a tacit commitment to collaboration and an informal network of back channels for communication and negotiation that eased the process of consensus building. In addition, there was a long history of interest in the region, especially among dischargers, in improving the monitoring system. A study of monitoring in southern California (NRC, 1990b) had provided an unbiased forum for "truth telling" about the flaws in the system and had led to a widespread (and public) acceptance of the need for change. A large existing body of scientific information and empirical knowledge about the ecological system provided a firm basis for proposing revisions.

SUMMARY OF THEMES

Certain common themes have emerged from these examples of existing coastal and marine programs and activities:

-

Every situation is different in terms of historical background, initiating events, leadership style and capacity, scientific issues, natural resources, organizational structures and flexibility, and the availability of scientific information.

-

Key initiating events, even if they seem negative (e.g., oil spills, tanker groundings, severe conflicts), can catalyze useful changes in behavior.

-

Focusing on a specific place or geographic area is necessary for creating a sense of shared purpose.

-

Valid, relevant scientific information can provide a sound basis for decision making.

-

The processes, even the successful ones, are chaotic and unpredictable, and favorable outcomes sometimes depend partly on sheer luck.

-

Skilled leadership is a necessity.

-

Successful leadership and decision making are characterized by a high degree of improvisation.

-

Organizational and behavioral issues are as important as scientific issues (often more so).

-

Collaborative processes are necessary to, but not sufficient for, success.

-

New, more flexible roles for federal agencies make novel solutions possible.

-

New forums for discussion and decision making can foster creativity.

-

Patterns of power sharing evolve.

Only a few of these common themes, particularly the need for valid scientific information and the importance of flexibility, correspond to the principles developed by the committee at the outset of the study (see Chapter 1). There are three reasons for this. First, the principles were developed in the abstract, without reference to specific instances of governance. Second, the principles refer in large part to final outcomes (e.g., improved economic efficiency, sustainable development) that are desirable from the perspective of society at large. In contrast, the common themes from the examination of existing programs and activities refer to more immediate, process-related issues of initiating and successfully sustaining and managing specific governance programs. Third, the principles implicitly pertain to larger-scale, more complete governance systems that have the ability to create these final outcomes. The common themes from the review of examples reflect the more fragmentary, piecemeal nature of real-world governance, which often focuses on a portion of the overall governance process.

Two fundamental lessons emerge from a comparison of the initial principles with the common themes drawn from real-world examples:

-

Opportunities for improving governance come in all sizes and shapes. Some are large-scale efforts that can influence final outcomes; others are smaller-scale ventures with more limited goals.

-

Organizational and behavioral issues are vital to every project, no matter what the scale.

In general, then, the common themes focus on process-related issues that are essential delivering the positive outcomes identified in the initial principles. Therefore, the committee determined that organizational issues should be further examined.