1

Introduction

BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW

Growing national interest in the ocean, awareness of threats to marine integrity, and opportunities to utilize marine resources make this an ideal time to explore a more coherent system of governance to guide activities in the ocean and coastal regions. Challenges to existing systems have arisen from changes both in national priorities and in the international economic system, including the recognition that good environmental policies make economic sense, the globalization of markets and opportunities, and a willingness on the part of the government to become a catalyst for technology development and economic growth as well as a steward of natural resources.

At the same time, demands on the coastal marine environment are intensifying through the continued migration of people to the coasts, the growing importance of the coasts and ocean for aesthetic enjoyment, and increasing pressures to develop ocean resources and space for economic benefits (e.g., commercial fisheries, transportation, marine aquaculture, marine energy, and mineral resources). The combination of these factors has created a sense of urgency for the development of a coherent system for making decisions in this arena (NRC, 1995c).

Although the marine environment is typically open to multiple uses, the United States now manages ocean and coastal space and resources primarily on a sector-by-sector basis. For example, to a large degree, one law, one agency, and one set of regulations govern offshore oil and gas; a different law, agency, and regulations govern fisheries; and other single-purpose regimes oversee water quality, navigation, protected areas, endangered species, and marine mammals (Cicin-Sain and Knecht, 1985). Although regimes for the management of resources are established on a statute-by-statute basis, each area of interest may, at the same

time, be impinged upon by a plethora of other regulatory management regimes. Except for the modest, but important, marine sanctuaries program and a few emerging state programs, ocean regions are not managed on an area-wide, multi-purpose, or ecological basis; nor are there agreed upon processes for making trade-offs and resolving conflicts among various interests (NRC, 1995c).

The single-purpose approach to management often leads to adverse ecological impacts, economic stagnation, and political gridlock. Single-purpose laws do not account for the effects of one resource or use on other resources or on the environment as a whole. They do not assess cumulative impacts, and, therefore, may not provide a basis for resolving conflicts. Even if a management regime encompasses both economic and environmental considerations, implementation in a specific situation has frequently meant not accommodating the concerns of conflicting interest groups. In the absence of an integrated framework, parties seeking to utilize ocean resources and space for economic objectives and parties concerned with environmental preservation often have to rely on the exercise of political power or litigation as primary mechanisms for achieving their aims. Significant societal and economic costs are incurred through these adversarial processes (Outer Continental Shelf Policy Committee, 1993).

Previous Marine Board studies of issues associated with the nation's ocean space and resources (NRC, 1989, 1990a, 1991, 1992a; Marine Board, 1993) have confirmed that the absence of a coherent national system of governance for marine

Container ship sailing into the Port of San Francisco. Photo courtesy of the Marine Board.

Searun, Inc., Salmon Farm, Eastport, Maine. Photo courtesy of Katharine Wellman.

resources and the use of ocean space have often led to economic stagnation and political stalemate. These reports have also concluded that a more coherent process for governing marine activities and resources would ensure that the nation's ocean ecosystems and their living resources were protected. At the same time, economic development would be allowed, where appropriate. In a coherent system, existing and potential conflicts among different users of the ocean would be anticipated and addressed through mechanisms for the equitable allocation of ocean space and resources in keeping with national stewardship over the region.

The general basis for this approach is articulated in a report by the President's Council on Sustainable Development (President's Council on Sustainable Development, 1996), in which a national commitment is made to ''a life-sustaining Earth.… A sustainable United States will have a growing economy…and…will protect its environment, its natural resource base, and the functions and viability of natural systems on which all life depends."

CHALLENGE OF MANAGING MARINE AREAS

Marine areas extending from the coastline of the United States to 200 miles offshore are immensely valuable resources to the people of the United States. They provide:

-

habitat for a wide range of plant and animal species that are essential to the global ecosystem

-

fish and shellfish that support the majority of commercial and recreational fisheries

-

reserves of oil, gas and other minerals

-

travel-ways for coastal and international shipping and the maneuvering area for the U.S. Navy

-

places for swimming, boating and other outdoor recreational activities that provide renewal and relief from the pressures of everyday life

-

a basis for the tourism and recreation industries

-

access to coastal development

-

important influences on the climate of coastal regions

-

essential aspects of our culture, traditions, and heritage

The marine areas that provide these benefits have always been publicly owned and open to all users. Within three miles of the shore, underwater lands are in the domain of the states. From three miles to 200 miles offshore, they are overseen by the federal government on behalf of all Americans. Sustaining the ecological health and economic productivity of this vast underwater commons requires careful, informed, effective, and decisive management.

Unfortunately, management practices have not kept pace with growing pressures on the marine environment. The population living in coastal areas has grown

Great blue heron, Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, Virginia. Photo courtesy of William Eichbaum.

rapidly (Culliton et al., 1990). Technology has extended the power of humans to exploit marine resources. The demand for products from our oceans, gulfs, and bays has increased dramatically. Individual users and interest groups have become more defensive about the benefits they obtain from coastal waters and more strident in their efforts to secure diminishing resources for themselves.

A wide range of state and federal agencies and programs have been created to respond to these pressures. In many instances, these programs have succeeded in reversing environmental decline and in resolving conflicts. But in a growing number of cases, the institutions responsible for managing marine areas have not anticipated the ecological risks of their actions or inaction, have not been able to coordinate and sustain efforts to solve large-scale marine management problems, and have been paralyzed by conflicts among interest groups.

The depletion of fish stocks the Gulf of Maine is the most notable recent example of the failure of the management of marine resources. The historic, and ongoing, decline of productive natural systems like the Chesapeake, San Francisco, and Florida bays is further evidence of the need to change our approach to marine area management (Fogerty et al., 1991; Hedgepeth, 1993). Global climate changes, continuing population growth, advances in mechanical, electronic, and biological technology, the expansion of international trade and incursions of nonindigenous species all suggest a need for more effective management of marine areas (NRC, 1995c).

DEFINITION AND SCOPE OF THIS STUDY

The process of marine area governance has two dimensions: a political dimension (governance), where ultimate authority and accountability for action reside, both within and among formal and informal mechanisms; and an analytical, active dimension (management), where analysis of problems leads to action. In practice, there is a continuum from governance to management. The country needs a coherent system of governance, based on a set of overarching principles and processes, and an appropriate set of management tools vigorously applied to deal with the unique characteristics of marine resources. A great many tools presently deployed in the marine and coastal environment embody one form of management or another. But there is no coherent system of governance.

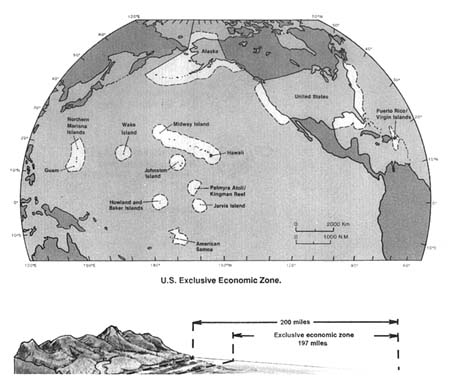

This study attempts to identify principles and goals, as well as elements, processes, and structures for improving marine area governance. The concepts outlined below are applicable in the marine environment, that is the area between the high water line and the seaward extend of the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).1 The geographic area of concern for this study is the marine environment

The Exclusive Economic Zone of the United States and its Trust Territories (shaded areas). Illustration courtesy of the National Ocean Service, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce.

of the United States, including coastal resources such as bays and estuaries, without regard to current determinations of jurisdictional authority between the states and the federal government.

The term "marine management area" used in this study refers to an area for which coherent plans are developed and measures taken to govern the uses of the area systematically. Types of marine management areas include sanctuaries, reserves, parks, and other units subjects to regional planning and management. Planning by states to manage their ocean and coastal areas also represent efforts to implement this concept. Certain federal statutes, such as the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA), the Fisheries Conservation and Management Act and the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Lands Act, have also established processes with some of the characteristics of marine area management.

Until recently, prohibiting or limiting activities in specific ocean areas has been the primary strategy for controlling development. This approach neither mediates differences among multiple users nor ensures ecological integrity. An

integrated system of governance is necessary for managing these regions and resources in keeping with the best interests of the nation—for present and future generations.

A number of federal and state agencies have jurisdiction over marine and coastal areas, activities, and resources. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is responsible for the marine sanctuary program; for fisheries management; and for providing states with a national framework for coastal management, including funding grants for ocean management planning. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is responsible for maintaining the quality of the nation's waters and has several regional planning programs that directly address the uses and management of ocean regions, such as the Gulf of Mexico and the National Estuary Program (NEP). EPA is responsible for designating and managing ocean disposal sites. The Minerals Management Service (MMS) is responsible for the management of outer continental shelf energy and mineral resources. The National Park Service has a number of ocean properties and management responsibilities, for example, in the Channel Islands, off California, and in the Florida Keys. The U.S. Coast Guard enforces laws governing fisheries and other laws pertaining to the oceans. The U.S. Department of State is responsible for the international implications of the regional management of marine resources and uses. The U.S. Department of Defense has a keen interest in marine area governance because of the relationship of ocean space management to national defense. States, international agencies, and other countries also have responsibilities and interests.

Some coastal states have developed comprehensive plans and policies for regulating or encouraging activities that affect their territorial waters and/or coasts, but the scope of their activities is limited by their state jurisdictions. The primary goal of these management plans is to ensure sustained, long-term benefits from coastal space and resources for present and future generations. States could be substantially assisted, however, by leadership from the federal government in dealing with regions that are beyond their legal purview but where they have strong interests.

VISION OF THE FUTURE

Defining basic principles and effective processes for the governance of ocean and coastal areas is a prerequisite to both sound economic investment and effective environmental stewardship and makes it possible to establish a reasonable, nonadversarial approach to resolving conflicts. A critical examination and assessment of current practices is the basis for developing a structure and processes for the future.

The Committee on Marine Area Management and Governance envisions an improved system of governance of the marine resources of the United States that would:

-

restore the ecological health and character of marine areas and sustain them permanently for the benefit of future generations

-

perceive risks to the marine environment early enough to take cost-effective measures to avoid both the irrevocable loss of ocean resources and unproductive conflicts among competing interests

-

enable citizens to enjoy the benefits of marine areas and resources

Principles for Marine Area Governance and Management

The committee first reviewed the background paper that emerged from the planning session for this project (Appendix B) and distilled several principles or criteria from it that define successful governance. Many of these principles reflect the 16-point "belief statement" that underpins the report of the President's Council on Sustainable Development (President's Council on Sustainable Development, 1996). The committee tested these principles in evaluating three major case studies and other examples of management described by participants at meetings in the case study regions. The modified principles became the following performance standards for successful marine area governance:

-

Sustainability. Sustainable use of the marine environment and resources requires that the needs of the present generation not compromise the needs of future generations.

-

Regional ecosystem perspective. Governance systems should be based on an understanding of the natural ecosystem. Strict adherence to political or jurisdictional boundaries can hamper effective governance where events, issues, and natural processes cross jurisdictional boundaries. The ecological region should include the adjacent terrestrial systems, as necessary to ensure effective resource management and governance.

-

Global imperative. Although good regional governance is essential for good management, global issues, such as global climate change, require major policy direction on the national and international level. The decision to address these critical issues cannot be made at the regional level although innovative measures for addressing them may be developed and implemented there.

-

Adaptive management. The system should be able to accommodate changes in scientific understanding and advances in technology and to recognize that social values can shift the fundamental requirements and constraints of governance. Management should be viewed as a learning experience for approaching future problems.

-

Scientific validity, including risk assessment. Governance decisions and decision-making processes should be based on biological, physical, chemical, and ecological information, as well as cultural and social norms. Governance should include an assessment of the potential risks of action and inaction.

-

Conflict resolution. The governance system should provide mechanisms for resolving conflicts that are fair and that reduce the delays associated with disputes.

-

Creativity and innovation. Governance systems should foster creativity and innovation by government officials and other affected parties. This means that measured risk-taking should be rewarded and that new approaches to old problems should not be rejected because of existing regulations or government structures.

-

Economic efficiency. The goal of governance and management should be to increase the total social value derived from marine resources. This requires giving appropriate weight to nonmarket resource values and service as well as commercial values.

-

Equity and transparency. The governing process and decisions for allocating benefits and costs should conform to accepted norms of equity. The governing process should establish a level playing field for competing stakeholders and users, provided that equity also extends to future generations. Transparency refers to the principle that everyone affected should understand how and under what conditions they can participate in the decision-making process.

-

Integrated decision-making. Governance structures should bring together the concerns of various agencies and stakeholders to encourage decisions that address ecological, social, economic, and political problems.

-

Timeliness. Governance systems should operate with sufficient speed to address threats before they become crises and to meet schedules mutually agreed upon by the participants.

-

Accountability. Authorities and structures for governance and management need to be clearly defined so that it is clear who is responsible for particular tasks and who must change policies or actions for the adaptive management process to be effective.

Underlying all of these criteria is the notion expressed in the report of the President's Council on Sustainable Development that "… in order to meet the needs of the present while ensuring that future generations have the same opportunities, the United States must change by moving from conflict to collaboration and adopting stewardship and individual responsibility as tenets by which to live" (President's Council on Sustainable Development, 1996).