Part III.

Determining The Legacy

WHERE ARE THE PEW FELLOWS TODAY?

|

Fellows and alumni are actively engaged in many dimensions of the historical changes taking place in the U.S. health care enterprise. |

The Pew Health Policy Program (PHPP) network is now 306 fellows strong, with representation in 35 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and five foreign countries (Pew Fellows News, Winter 1996). Fellows and alumni are actively engaged in many dimensions of the historical changes taking place in the U.S. health care enterprise. If key roles at national meetings and significant representation in the peer-reviewed literature and major studies are reliable indicators, then Pew fellows, old and new, appear to be deeply involved in some of the leading analysis, demonstrations, and policy and political work that will help determine the landscape of tomorrow's health care system (Pew Fellows News, Winter 1996).

Career Trajectories5

Richardson's 1990 evaluation of the PHPPs established that the majority of alumni were involved in health-oriented professions (Richardson, 1990). Most of the alumni entered the PHPPs with considerable experience in health care and health policy; therefore, their overwhelming representation in health-oriented fields is not surprising. Nevertheless, it is interesting to explore the specific subfields of health that alumni chose to work in following completion of their fellowships.

Richardson (1990) states that when the PHPP was being developed in the early 1980s, there were general perceptions of the nature of the positions that program graduates would seek. Some Advisory Committee members thought that many doctoral program graduates would seek faculty positions, whereas other committee members expected graduates to look for positions in the legislative setting, as policy analysts, or as general policy experts. Richardson

(1990) reported on the distribution of program alumni by the nature of their positions, classified as policy analysts, general policy, faculty, and administrative. He found that the majority of alumni were in general policy positions. The general policy category used in his analysis was broad in scope, incorporating everything from hospital association vice president for governmental affairs to a senior policy analyst in the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) to a program officer at a foundation.

Richardson (1990) interviewed the alumni to determine what extent their professional positions included the health policy domain. He found their overall policy orientation to be very high. Richardson (1990) also asked to what degree PHPP influenced subsequent professional activity. He found that doctoral students from the Boston University(BU)/Brandeis University program and the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA)/RAND program considered PHPP's influence to be greater than postdoctoral and midcareer alumni did, which stands to reason because the individuals in the latter two groups were already engaged in careers at the time of their graduate training.6

Of the 301 PHPP participants in 1996, 54 are postdoctoral alumni from the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) program and 152 are doctoral alumni from all four program sites: the University of Michigan (46 participants), Brandeis (44 participants), BU (22 participants), RAND (18 participants), UCLA (15 participants), and UCSF (7 participants). Twenty-seven are policy career development fellowship alumni from RAND, 18 are midcareer fellowship alumni from UCSF, and 6 are management fellowship alumni from UCSF. The remaining 44 fellows are considered current fellows, meaning that they entered the programs between 1994 and 1996. Of the current fellows, 7 are doctoral fellows at Brandeis, 13 are postdoctoral fellows at UCSF, and 24 are doctoral fellows at the University of Michigan. As of 1996, 59 percent of all Pew participants are women.

Professional Distribution

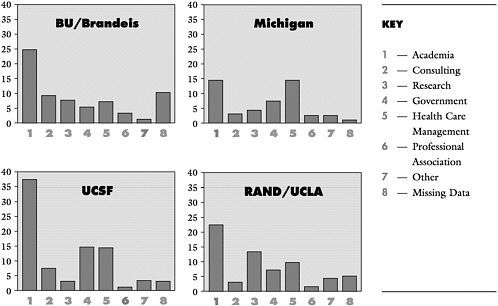

Figure 1 presents the professional distribution of PHPP alumni by program site as of 1996. Table 2 provides a breakdown of the career categories used to demonstrate the professional distribution of PHPP alumni. For four PHPP sites, the largest number of fellows graduate into academic positions. UCSF alumni have the largest representation in acad-

emia, with 46 percent of their alumni holding university-based positions. Thirty-seven percent of all BU/Brandeis alumni and 33 percent of all RAND/UCLA alumni enter academia upon completion of their programs. Although academic positions represent the largest percentage of all positions held by Michigan alumni (28 percent), positions in health care management represent a close second (26 percent of all Michigan alumni). Consultant positions account for the second largest group of BU/Brandeis fellows (13 percent of all current alumni), with the health care management sector and the private research sector representing the third largest groups (10 percent of all alumni each). Seventeen percent of UCSF alumni are in health care management, and another 17 percent are in government positions, representing the second and third largest groups of alumni, respectively. The second largest percentage of RAND/UCLA alumni (20 percent) are in private research positions, 16 percent are in health care management, and 12 percent are in government.

Pew alumni hold highly influential positions in strategic and highly visible areas of academia, consulting firms, health care management positions, all levels of government, private research organizations, professional associations, and various

Figure 1.

Professional Distribution of PHPP Alumni by Site, 1996

other fields. Table 2 presents the actual number of alumni currently in each sector. As of 1996, 37 percent of all Pew alumni are employed in academic positions as faculty, researchers, and academic directors. Many of these positions are in health policy departments and institutes, although a specific teaching or research focus was not determined. The second largest sector as a whole to employ Pew alumni was health care management (17 percent). Fellows employed in this sector primarily manage hospitals, direct private health organizations, and manage clinical departments. Fourteen percent of all Pew alumni are employed in government positions. At the federal level, alumni hold positions in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, and the National Institutes on Aging and Drug Abuse, to name a few. Alumni also hold positions in the U.S. General Accounting Office, the U.S. Public Health Service, and in the Medicare and Medicaid programs in the Health Care Financing Administration.

|

Pew alumni hold highly influential positions in strategic and highly visible areas of academia, consulting firms, health care management positions, all levels of government, private research organizations, professional associations, and various other fields. |

Ten percent of all Pew alumni are employed in the non-university-based private research sector as of 1996. Another 8 percent of alumni work as health policy consultants, some in private firms, others with public organizations, and several in private practice. Three percent of Pew alumni are employed by various professional associations including the National Women's Health Network, the Oregon Nurses Association, and prestigious foundations. Four percent of Pew alumni are working as health care providers and health lawyers, and a few are in non-health-related sectors. Current employment data are missing for 7 percent of Pew alumni.

It should be noted that although the tables and figures differentiate between professional positions, the categories are not always mutually exclusive. For example, there are cases in which university-based faculty are also involved in health policy making at the government level. Furthermore, the ''other" category should not be considered less health policy related, because many alumni in law and other sectors could be directly involved in health policy analysis and development. At least two Pew alumni practice law in non-health policy-related firms but focus exclusively on health-related or health policy-related issues. Leighton Ku made some insightful comments regarding this issue that should be taken into account when reading the information in the tables and graphs. Ku is working at the Urban Institute and is involved in health policy and health services-related research. He explained that comparing his position to that

Table 2. Breakdown of Career Categories, 1996

|

Government (35) Federal Offices Directors Project Leaders Health Policy Analysts Examples: U.S. General Accounting Office U.S. Public Health Service U.S. Congress Health Care Financing Administration Environmental Protection Agency Agency for Health Care Policy and Research National Academy of Sciences National Institute on Aging National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism |

|

International Director of Health National Expert Examples: Aga Khan Health Services, France European Commission, Luxembourg |

|

State: Departments of Health Health Commissioners/Directors General Counsel House Chairman Examples: Rate Setting Commission Offices of Statewide Health Planning & Development Departments of Health State Medicaid Programs Local and County Health Departments Joint Committee on Health Care |

|

Academia (98) Faculty: Assistant, Associate, Full Deans Department Chairs Research Associates (university-based) |

|

Consulting Services (22) Consultants Examples: Private Independent Contractor On Lok Senior Health Services |

|

The Lewin Group The MEDSTAT Group Interactive Technologies in Health Care California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform |

|

Research (Non-university based (28) Research Associates/Scientists Examples: National Institute of Health Care Management RAND Latino Health Institute Sarah Shuptrine and Associates The Urban Institute Multicultural AIDS Coalition New England Research Institute |

|

Other (10) Occupational Health, Industrial Hygienist Business (non-health) Physicians & other providers (non-academic) lawyers |

|

Professional Associations (8) Directors/Chairs Examples: The Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation National Women's Health Network The Cleveland Foundation Washington Health Association Oregon Nurses Association Carpenter's Health and Safety Fund National PACE Association Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation |

|

Health Care Management (45) Assistant Hospital Administrators Hospital Administrators/Directors Chief Executive Officers Clinical Directors Hospital Presidents/Vice Presidents |

|

NOTES: Examples of categorical titles are derived from the directories of Pew fellows and alumni (see Appendix D for examples of exact titles). Alumni from classes entering 1983–1993 are included. Insufficient data were available for 18 alumni. Number in parentheses are numbers of alumni. |

of someone working in government might lead to the conclusion that he has less influence over policy; however, this would be incorrect. Among Pew fellows, Ku had a unique perspective on how to have an influence while working outside government:

[W]hen you're in government ... you're always sort of fitting in and just trying to keep up with a broader administrative agenda for the administration and/or for Congress. You can shape things, but you're shaping things within that context. If you're on the outside doing policy research, then you can try to shape the agenda somewhat. Whereas when you're working in government, the way the government is set up, it's very hierarchical. Basically speaking, most government people work in relative anonymity and information goes up the administrative hierarchy and then occasionally goes across into other policy circles, whereas if you're on the outside at a place like the Urban Institute you can deal on lots of levels with policy makers in government, in the executive branch, in Congress, at state levels, and with some other associations.

Movement Between Professional Fields

Table 3 depicts the movement of all fellows between professional fields before and after their participation in PHPP. This matrix allows the reader to determine the percentage of fellows who were in a particular field before the Pew program and then the percentage who changed fields after completing the program. The shaded diagonal represents the percentage of fellows who are employed in the same field in which they were employed before starting PHPP. The career categories used in this matrix are the same as those listed in Table 2. It is noteworthy that 70 percent of all fellows who entered the Pew programs from academic positions remained in academia after completing the program. On the other hand, only 20 percent of all fellows who were employed in the private research sector before entering the program remained in that field. Sixty percent of these fellows entered either government or academia upon completion of the program (30 percent each). Thirty percent of all fellows who were in government positions prior to entering the Pew program remained in that sector. However, as with all categories, this does not imply that they remained in the same position. Appendix D provides some examples of career trajectories and title changes. It should be noted that the titles presented in Appendix D and those used to determine categorization are the fellows' titles immediately before they entered the program (retrieved from the directory published during the year that the fellow entered the program)

Table 3. Professional Distribution of PHPP Alumni at the Start and End of Program, in percent

and then the most recent title listed in the 1996 directory. All positions held between these two points in time are not included in this simple analysis. Nonetheless, it is interesting to see the broad changes in the titles of the fellows before and after participating in the Pew program.

Table 3 does not present title changes by program site; however, a brief discussion of some of the most interesting career trajectories specific to the various programs may be of interest. One of the biggest changes can be found among the Michigan Pew fellows. Before entering the program only 8 percent of all Michigan fellows were employed in academic positions. After completing the program, however, 28 percent of all alumni entered academia. The other large change found among Michigan fellows is in the opposite direction, with 32 percent starting out in government but only 16 percent employed in that sector as of 1996. Several other large changes in career occurred among the BU/Brandeis alumni. Before entering the program, only 21 percent of all fellows were in academia, but after completing the program this number jumped to 37 percent. BU/Brandeis fellows also experienced a 10 percent increase in alumni working in the private research field (0 to 10 percent). Interestingly, before entering the program, 28 percent of all BU/Brandeis fellows were employed in the government sector. After completing the program, however, only 7 percent remained in that sector. A second shift experienced by the BU/Brandeis fellows is in the field of health care management. Twenty-five percent of all fellows were employed in health care management positions before entering BU/Brandeis, but only 10 percent are currently employed in that field.

Fellows in the UCSF and RAND/UCLA programs experienced the fewest career shifts between the time of entry and completion of the Pew program. For the UCSF program this makes the most sense because its largest program was a postdoctoral fellowship, and it can be assumed that most fellows come in from academia and graduate back into academia at higher levels. This is in fact the case, with 41 percent of UCSF fellows starting off in academia and 46 percent of alumni currently employed in academic positions. For the RAND/UCLA fellows there was no change in the percentage of fellows who began the program in academic positions and the percentage of those currently in academia: 33 percent at both the start and finish. There was a large jump, however, in the number of RAND/UCLA fellows who are currently in the private research field (20 percent) as opposed to the percentage of fellows originally employed in

that sector (9 percent). Again, it should be noted that these percentages are not based on matched groups. The 33 percent of RAND/UCLA fellows who were employed in academia prior to beginning PHPP may be a set of people completely different from the 33 percent currently employed in academic positions. For a sample of match career trajectories, see Appendix D.

IMPORTANCE OF DOCTORAL PROGRAM COMPLETION

Doctoral Completion Rates

Table 4 depicts the doctoral degree completion rate for all programs as of 1996. BU/Brandeis and Brandeis alone (after 1991) offered a doctoral program every year that they received Pew funding. The last year that Brandeis granted Pew fellowships was 1995. BU's average completion rate as of 1996 was 59 percent; for Brandeis it was 70 percent (81

Table 4. Proportion of Pew Doctoral Fellows Who Competed Degree, by Program Site, 1996, in percent

percent if the entering class of 1992 is excluded). The University of Michigan offers doctoral programs every other year that it receives Pew funding, with the 1997 year being the last. Their average completion rate as of 1996 was 50 percent. UCLA and RAND offered doctoral programs up to the completion of the second funding cycle. Their completion rates as of 1996 were 80 percent and 89 percent respectively. UCSF phased out its doctoral program early on; however, it offered doctoral training to seven fellows, and its completion rate was 71 percent. The doctoral completion rate for the entire PHPP as of 1996 was 66 percent (97 of 148 fellows in the classes of 1983 to 1992). This overall completion rate compares quite favorably to national completion rates. According to Bowen and Rudenstein (1992), about 50 percent of all students entering PhD programs eventually obtain doctorates, many after pursuing their degrees for anywhere from 6 to 12 years. The completion rates for fellows in PHPP as a whole and the individual PHPPs have therefore exceeded the national average.

Raskin and colleagues (1992) state that although most of the Pew students at BU/Brandeis completed their course work and qualifying examinations within the first year and a half, few fellows actually completed their dissertations within the projected 2-year period. Of 60 doctoral fellows admitted from 1983 to 1992, only 4 actually completed the doctorate within the 2-year time frame. As of 1996, the average time for completion of the program at Brandeis, including the dissertation, was 3.8 years. For BU the average time to achieve the doctoral degree was 3.7 years, for RAND the average was 4.7 years, and for UCLA the average was 5.2 years. Perhaps the most impressive time to completion was for Michigan fellows, who work full-time while in school full-time, which was an average of 5.2 years.

Effect of Program Noncompletion

|

The completion rates for fellows in PHPP as a whole and the individual PHPPs exceeded the national average. |

The faculty who were interviewed were confident that the fellows who did not finish their doctoral degrees were still better prepared to face the challenges of today's health policy world because of their experience with PHPP. All of the fellows who had not completed their doctorates were engaged in important work. Nonetheless, all of the interviewed fellows who had not yet completed their degrees said that they fully intended to finish (and several did between the time of the interview and the completion of this report). Interestingly, many of the fellows who had not finished were in posi-

tions that they intended to stay in, even after they received their PhD or DrPH. This implies that for many fellows the completion of the doctorate was motivated by personal needs and not because it would change their status or rank.

|

Fellows spoke about the importance of finishing their degree not only for themselves but also because that was the "contract" that they had made with the Pew Charitable Trusts. |

Dan Rubin believes that he is better at what he does today because of his Pew doctoral training at Michigan. Even though he has not yet completed his degree, he is in an influential, professional position where he uses his interdisciplinary policy analysis skills every day. His job is to connect pieces of government roles that relate to health care quality and information use. Rubin's professional activities require him to use his judgment about what needs to be related to what and how this can be done in an efficient and politically acceptable way, rather than about how to assemble a research plan for a study; yet, he has every intention of completing his dissertation and thus his DrPH. Why?

[T]he intellectual closure of doing extended work. One of my personal reasons to do the program was for me to see what it really took for me to do extended work. The bread and butter of government work is not extended, analytic ventures. Sometimes there is extended writing and certainly extended thinking about a topic. But, the kind of effort involved in writing a dissertation is very important for me to learn, and for me to learn about myself.

In thinking about the value of a program like this for people who choose not to complete the dissertation, Rubin stated that if what was learned was a new interdisciplinary perspective, it would be of very high value. For someone like himself who had master's training in policy analysis that was interdisciplinary in nature, stopping the doctoral program after classes would still enrich his knowledge base, but in a very expensive and inefficient way for the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Other Comments About Doctoral Program Completion

Keeping in line with Dan Rubin's comment about the Trusts, other faculty and fellows spoke about the importance of finishing their degree not only for themselves but also because that was the "contract" that they had made with the Pew Charitable Trusts. Jonathan Howland stated that the foundation was paying the tuition for the fellows and granting them a stipend in exchange for something. Thus, not completing the degree was in essence not taking that "deal" seriously. He laments the fact that some fellows do not see the issue from

the perspective of a program that invested in them to do something rather than from a purely personal point of view.

Pamela Paul-Shaheen started her doctoral program in 1984 and completed her degree June of 1995. She explained that there were two reasons why she kept at it:

First of all, because if I start something, unless there are things in life that I cannot change, I will finish. Also, because people made a commitment to funding my education. Had I not finished I would have reneged on a commitment I made.

Patricia Butler explained that at Michigan, the goal of the program was to train the fellows to be policy analysts rather than health services researchers. Therefore, she acknowledges the fact that in her subsequent professional activities she will probably never again conduct research quite at the level of the dissertation. However, she believes that it is extremely important for policy analysts to be able to understand the process of collecting original data, how to work with secondary databases, and how to use the data:

Because of my age and because of my existing experience, I don't happen to think the degree is that important. But I do plan to get it because I've come this far and because I feel that it is an indication of successfully completing something. The dissertation is a wholly different experience making me understand just how laborious the research experience is.... Prior to this I had no true appreciation of what it was like to start from an idea and think about data sources and take it all the way. Understanding of the research process is very valuable to me. (Patricia Butler graduated in May 1996).

Steve Crane underscored Butler's point about PHPP goals not being to have the fellows go on and get a tenured track position per se but, rather, to be capable of effecting great change. When asked whether this meant that in fact the PhD degree was an inappropriate degree for this type of programs, Crane said:

Ah, that's the big question. We ran into a lot of problems because it was a traditional PhD as opposed to a DrPH, as opposed to a super master's degree. What was important about the level of education that we were talking about were a couple of things: (1) emphasis on research methods and being not only a consumer of research, which you become with a master's degree, but a producer of research, which is signified by a PhD. People needed to have that knowledge whether or not they needed the degree for their careers.... From a marketing point of view, the PhD was really important. I think Michigan folks will feel a little badly about the DrPH because it's considered to be a professional degree, which in the end is probably a more appropriate degree for this program. So on balance I think the PhD has real

value, signifying both the level at which you're working and your capability for independent research.

|

It is extremely important for policy analysts to be able to understand the process of collecting original data, how to work with secondary databases, and how to use the data. |

Nonetheless, Crane commented that whether the fellows finished the degree or not, the Pew program accepted them as an "equal part of the club." He explained that the programs do not discriminate on the basis of whether someone completed the degree, although completion is certainly celebrated. He attributes this acceptance to the fact that Pew's "focus was more on what you're going to do, not on who you're going to be."

Marion Ein Lewin reiterated Steve Crane's final comment about Pew's philosophy on fellows who have not completed their degree. She stated that those fellows that went through the whole 2 years or so of course work and then did not get the degree are still considered Pew fellows in discussions and are included in the Directory. She believes for the most part that there really is no distinction between the completers and noncompleters, even though the purpose of the program is clearly for people to get their degrees:

My feeling is that programs like these have a halo effect. Even if you didn't finish, you participated at least for a time in a very exciting learning activity, you met the people, you got a lot of value even if you didn't get the degree. If you look through the list [of fellows] in an analytic way, there are a lot of people who haven't gotten their degrees who are playing very important roles. We accept them in the "family."

Some fellows and faculty, however, believe that the fellows who do not complete the dissertation miss out on the real or whole value of the program. According to Linda Simoni-Wastila, the course work was the easy part and merely forms the foundation for the dissertation process. She stated that it's not the courses or the comprehensive exams that pull all the knowledge together; rather, it's the dissertation. Stan Wallack agrees that it's the dissertation that really forces the fellows to take a problem and analyze it completely.

Still, there are others, like Dennis Beatrice, who did not finish the program but who feel that they gained a better understanding of how to use analysis and graduate education training in nonacademic settings. Dennis Beatrice stated that "there is great utility in Pew training," regardless of whether a fellow completed the program.

UNCOVERING THE PHPP LEGACY

At the Pew Health Policy Program Advisory Board Meeting in January 1992, participants raised the topics of program

institutionalization and legacy. Grantees were informed that they should all be exploring and negotiating for heightened institutional support for the future. Participants at the meeting discussed the fact that even if the current programs were not able to attract sufficient external funds to continue their full operation, they should be able to show that the program has enabled the development of an advanced health policy curriculum and that it has influenced the outlook and teaching of program faculty. The program should be able to show that it has provided students with a much needed source of funding that enabled them to concentrate their dissertations on health policy rather than health services research (for which funding is available by more classically oriented federal funding agencies). The programs should be able to show that their fellows have had substantial interaction with policy makers through the meetings for new fellows in Washington, D.C., and other efforts at the funded sites. The programs should be able to show that the annual meetings have facilitated an important network and critical mass for interacting and discussing key issues. Another indicator that the program had an impact would be to show that the program influenced universities to value health policy research and to develop a high-level mentoring network. Program enhancement activities that build on the activities of professional associations such as the Association for Health Services Research (AHSR) foster the legitimacy of policy research by providing a forum for presentations and journal publications.

Therefore, what can be said about the success of the programs? Many of the challenges stated above were indeed met by the program sites, as indicated throughout this report. Many of the programs far exceeded the initial goals by instituting the curriculum and the training philosophy and by applying for and getting new funds, such as Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) training grants, to maintain their programs. What can be said, however, about the actual impact that the Pew program has had on the field, on the educational landscape, and on the fellows? Interestingly, all faculty and alumni interviewed were initially skeptical about making statements about the Pew legacy. Most were unsure about whether Pew's legacy could be defined or measured. Many felt that it was too early to determine what the program's legacy is and that this review should be conducted again in 10 years. However, after stating their hesitancy at making causal assumptions, all interviewees offered suggestions about how one could measure the value added by a program like PHPP, and many gave

examples of how PHPP has affected the health policy field and education and even provided ideas about what they thought best represented the Pew legacy.

Hal Luft, Stan Wallack, Stuart Altman, and Al Williams commented that measuring success for programs like these is difficult. One way they suggested that success, and thus the value added to the field, could be measured would be to look at where the alumni are, look at what they are doing, and determine if they are doing the things that the program wanted them to be doing. Hal Luft stated that most alumni are doing things related to health policy in various kinds of settings. He believes that many of these people would not be doing this type of work if they had not gone through the Pew program. According to Dr. Luft, that is the ''best implicit measure of success."

|

Many of these people would not be doing this type of work if they had not gone through the Pew program. That is the best implicit measure of success. |

Leon Wyszewianski stated that looking at alumni representation in the literature is one way to measure contributions to the field; however, Steve Crane is concerned that this would miss other aspects of the influence of the fellows. He stated that it's not the degree or the peer-reviewed publication that measures success; rather, it's the softer measure of what's being contributed to the field and the extent that the alumni are in demand in the system. Leon Wyszewianski does not disagree with this and recommended that another way to measure value added to the field would be to see if alumni changed direction from non-health-related policy work to health policy-related work and to determine if what they do currently differs from what they did before their Pew experience (see Table 3 and earlier discussion).

Informants' Reflections on the Meaning of Legacy

To understand the meaning of "legacy" the interviewees were asked to frame their experiences in terms of the legacy, Steve Crane said:

The Pew legacy is really trite but true, and you've heard it before, the people who were trained. Even though we took in more mature students, some of whom are now in their 50s, they're still a huge crop of people coming along who are going to make a huge difference. I'm not sure that we've seen yet the contributions to health policy that the Pew students are going to make. It takes awhile. But as these folks come up and go through leadership positions, I think we'll see more and more. That emphasizes the importance of trying to keep this group together as well as having them interact with some of the other program fellowship people who are around (eg., the Johnson program and the Kellogg pro-

gram). All these people are unique, they are leaders and they are going to make a contribution. The group effort is only going to enhance their already evolving skills.

Almost every person interviewed stated that it was indeed the fellows themselves that best represented Pew's legacy to the health policy field and to health policy education. Leighton Ku articulated a commonly held view of the legacy as "nothing brassy and shiny"; rather, it's "the people." Many agreed.

Legacy as Bridging Theory and Practice

|

Almost every person interviewed stated that it was indeed the fellows themselves that best represented Pew's legacy to the health policy field and to health policy education. |

In an effort to tease out exactly how the alumni translate into value added for the field, it was necessary to think about what was happening in the field prior to the Pew programs. Bill Weissert commented on the fact that the true legacy was in the trainees' accomplishments and in the higher level to which they are bringing the health policy debate:

There is an awful lot about the policy process that is still happenstance and convenience regarding who is around. You can only improve the chances that rationality will play a part in policy by having a lot of people around who are trained rationally. So, the more people you put out there, the better chance you have to formally or informally influence the policy process. We train a lot of people who are interlopers or daily workers in the policy process; therefore, we increase the chances that what comes out the other end will be better informed than it would have been if people had been shooting from the hip. Yet, its awful hard to quantify.

Furthermore, Bill Weissert believes that the Pew program made a lot more people aware of the power of the literature to answer a lot of questions in a systematic way rather than guessing as they were doing before. Hal Luft believes that the Pew program has influenced health policy in several subtle ways:

It is hard to identify specific policies that have changed one way or the other as a result of the Pew program, per se. I'm not clever enough to picture an alternative universe in which there wasn't a Pew program and what would have been different. But I do have the sense that some of the fellows have been doing very exciting things that are having impacts on the way the health care system and health policy is being done and how health care systems are changing with health services research, etc., that probably would not have happened had those people not gone through the Pew program.

Legacy in Terms of Scale and Scope

Several people interviewed mentioned the "scale effects" of the Pew program's legacy. John Griffith stated that the com-

munity is so big and diverse that it is difficult to speculate about the value added by training a small cohort of people. He stated, ''the community is many times bigger than the output stream." Nevertheless, says Griffith, in the 15 years since the program started, there has been a noticeable increase in the willingness to use empirical data as a basis for conclusion. He also indicated that even though the cohort may be much smaller than the community to which it is attempting to infiltrate, it must be remembered that health policy is a context in which a critical few in strategic locations can make a big difference.

Stuart Altman appreciates the difficulty in quantifying the actual impact that the Pew program has had on the health policy field; however, he does believe that the program was successful:

I think [the Pew programs] demonstrated that these programs are important, that they can produce value added. I know the most difficult aspects of evaluating a program, Pew or any other program, is determining what is the "value added." What is the value added to the individual and what is the value added to the system. Now, it's a little presumptuous of us to think or attribute to any one program, even one that has trained a couple of hundred people, what impact it has had on a one-trillion-dollar industry that affects every American, that employs one out of seven people; let's face it, we are dealing with a gigantic industry. We have to evaluate its impact on the margin. [However] Pew clearly did demonstrate the importance of interdisciplinary research.

|

Even though the Pew cohort may be much smaller than the community to which it is attempting to infiltrate, it must be remembered that health policy is a context in which a critical few in strategic locations can make a big difference. |

Joan DaVanzo acknowledges that the policies that the Pew fellows are ultimately aiming to change or influence in some way are far-reaching and that the health care field is indeed very large. However, the circle of actual policy makers and policy researchers is much smaller, and it is this sector of the health care field the Pew alumni can affect:

Pew brought a broader range of individuals to the field, so [the legacy] is a thing about people. The Pew model, and I don't know [how] much of the curriculum at the schools was the same, but it seemed to me that ... we all had a fairly similar analytic strategy, if you will, across the set of programs.... I don't know the influence of having this bulk of people that have that same view of the world dropped onto the health policy arena. I would think that it shapes the construct, enriches it, and gives it more depth. On one hand it's a grandiose statement to make; on the other hand it's really not. If you think about the economics of the health policy field, it's really a small field, and if you get that many people, what about 200 or so, with the same combination of skills, yet with varied backgrounds and expertise, the scene is hit from many different levels.

Legacy as Information Processing and Dissemination

If the term legacy can be defined as "accomplishments," then Kate Korman believes that the most important contribution of PHPP may be its success at seeding the health policy field with fresh, talented change agents able to communicate effectively with all players in the health care system:

|

What resulted were complementary programs that had the magnitude and depth to enrich the field and inform the debate. |

The most important contributions may be the richness of the health policy community today, which boasts 250 additional minds responsible for health policy decision making in a wide variety of venues: local, state, and national government, private foundations and institutions, and universities and research institutes. The ripple effect of this knowledge and expertise is found in the lives and future endeavors of those whom past fellows influence. Whether it be a change in policy at the local level or the influence of a teacher for a student to pursue a change in career in health policy, the ramifications are far reaching.

Marion Ein Lewin agrees that PHPP has enriched the field of health policy research in a remarkable and significant way, both in the quality and in the level of people that it was able to attract:

This program came along at a time when health policy research was becoming increasingly recognized as an important discipline and health care programs and budgets were becoming a significant aspect of public, federal, state, community, and private-sector budgets. Until the Pew Health Policy Program came along there were not many people who were good at both policy and who had the analytic skills to really understand what these dynamics were all about; how to develop a changed agenda. My feeling is that this program really enriched the field. To the degree that it was multidisciplinary and to the degree that there were individual programs, that was also a very significant and valuable accomplishment.

Marion Ein Lewin explained that all the fellows in all the programs were trained in statistics and analytic skills and were given a knowledge base in policy research, but as discussed earlier, all brought different expertise to bear on an issue. What resulted, says Lewin, were complementary programs that had the magnitude and depth to enrich the field and inform the debate. Furthermore, says Lewin, when you look through the literature at how the fellows are represented and when you look at what areas and activities the fellows have participated in, you see a reflection of the world of health policy and health care reform in the last dozen years.

Legacy as Professionalization of Health Policy

Many others agreed that the Pew program was instrumental in raising the awareness of health policy as an important area

for advanced graduate training. Al Williams commented on how he views Pew's impact on the field:

|

The Pew program helped to take academic health policy out of the traditional areas with which it has been predominately associated: hospital administration and economics. |

I think as a whole the Pew fellows have gone toward policy in a more focused way than people in the past. [Pew] emphasized policy. The emphasis was different across the set of programs, but the policy side was more focused than I think is common. When Paul Ginsburg was running PPRC [the Physician Payment Review Commission], he hired several of our graduates and specifically noted that he preferred our graduates because while he needed people with strong analytic skills, he also needed people who had a background in the health care system and health policy. We created that mix of skills that set our fellows apart.

Kate Korman explained that fellows have faculty positions in universities throughout the country and are in the process of passing on to new health policy analysts the gems of their training. Pew-trained faculty are replicating PHPP at new sites, thus the true definition of "seeding the field." Carroll Estes agrees:

I think the Pew program has very successfully seeded the field with competent well-trained scholars at government levels, nonprofit and foundation levels, and university levels. The flowering and capability of those fellows and their contribution are beginning to be recognized at fairly significant levels.... The most important contribution of the fellows is a passionate commitment to health policy and health services research that is objective and has an impact and the ability to carry out that work either directly themselves or to stimulate organizations and institutions to do it where they are.

Leighton Ku has also observed changes in the health policy program scene and attributes that partly to the accomplishments of PHPP. He states that there are many more health policy programs than there were prior to the initiation of PHPP. He believes that the Pew program helped to take academic health policy out of the traditional areas with which it has been predominately associated: hospital administration and economics. Ed Hamilton also discussed Pew's legacy for the health policy field in his 1995 evaluation:

[T]he Pew Charitable Trusts-funded effort was one of the early and influential stimulants to what became, over time, a sizable expansion of rigorous health policy training during the past dozen years. This has, in turn, elevated the technical debate about health policy options and implementation to a markedly more sophisticated level.... [T]he PCT was ahead of most other major private funders in perceiving the importance of cross-disciplinary training in this area, and its 245 trainees, while not a substantial fraction of all individuals employed by public and nonprofit entities in positions like the ones they occupy, seem like-

ly to make up a non trivial element of the vanguard of such people who have emerged as the health policy debate has gathered strength.

Legacy as Offering New Conceptual Models

Kathleen Eyre explained how she believed the legacy for the midcareer programs differed slightly from that for the other programs, in that it introduced a paradigm, or a new way of thinking, for existing professionals:

We all came out of professional positions... came in with our own professional set of skills and analytic tools and what we were introduced to for the first time was a rigorous policy analysis paradigm and way of thinking, the kinds of questions to ask, the different disciplines that influence policy, and we, in our brief year, were exposed to all kinds of different academic settings and disciplines.

|

This is a high-quality way to approach policy, and it does not mean that policy is not carried out in a political context. |

Terry Hammons expanded on this, discussing how at RAND the principle accomplishment was to have pulled a number of experienced people into an environment where they were able to become valuable contributors to health care policy in both the private sector and the public sector. What made this accomplishment so valuable for the field, explains Hammons, is that the fellows were trained to do this in a way that grounded policy making in research. He believes that this is a high-quality way to approach policy, and it does not mean that policy is not carried out in a political context.

Legacy as the Future Impact

According to Pamela Paul-Shaheen, the legacy diffuses "through the individuals who were involved"; however, she provided a reminder that the most important contributions to policy may not yet be noticeable. Paul-Shaheen stated that the "proof" will be even more noticeable in the next 20 years as the fellows mature into the elite policy positions. The fellows need time to move through the system. Nonetheless, she believes that some of Pew's effect can already be seen:

In the aggregate, in terms of the totality of the program, the jury is still out. But clearly the program has put a number of people into key policy positions. You can see the success of the program as you look across a spectrum of alumni and the roles that they are playing across the nation, regardless of whether they completed the program totally or not, many have moved into reasonably influential positions.

The Legacy in Summary

Steve Crane summed up what he thought represented all the legacies that are attributable to the Pew program: (1) the quick PhD was pioneered by the Pew programs, and as many problems as successes were found; (2) the focus on change; (3) the multidisciplinary and multisectoral approach; (4) the importance of discussion; and (5) the ability to take the mature learner into the system and have him or her succeed.

|

As a result of the Pew training approach, the fellows are better trained to bridge the gap between policy research and policy making. |

In a recent article written for the anniversary of the Institute of Medicine (1996), Stuart Altman described PHPP as a program that "tackles what some believe is the great divide between health economists and other disciplines, bringing the synergy of an interdisciplinary approach to problem-solving." He believes that the Pew program offers a truly unique opportunity for advanced interdisciplinary training in each of the four sites. Integrating fellows from various disciplines, including economics, political science, sociology, law, medicine, and other health-related professions, "fosters a cross-fertilization of different theoretical perspectives, as well as different methodological approaches in solving concrete policy problems." Altman provides an example:

[T]he deeper appreciation of the dynamics of competing political interests and how there interests are played out in the policy process offers a useful complement to an understanding of the economic implications of a specific financing strategy proposed for Medicare. In the same way that the RWJ [Robert Wood Johnson Foundation] program provides an environment of understanding between hands-on managers and clinicians and those familiar with the policy process, so too the Pew fellowships offer a creative linkage between the old vanguard of health policy analysts and those with a more interdisciplinary approach.

Altman acknowledges the tension between depth and breadth in a program such as PHPP, incorporating an interdisciplinary approach. He recognizes that one might argue that doctoral-level training should be grounded in one particular discipline. However, Altman states that as a result of the Pew training approach, the fellows are "better trained to bridge the gap between policy research and policy making." The value of interdisciplinary training has been underscored by the fellows themselves throughout this report.

In his 1990 Report to the Pew Charitable Trusts, Bill Richardson discusses the degree to which the various PHPPs complement each other. He states that although each institution provided a unique setting and structure, each served a common set of interests and goals. Hal Luft agrees:

Among the main things [that Pew accomplished] is that we've developed an integrated program across three or four sites that involve a wide range of people from fresh graduate students to fairly senior career people. We have placed those people into various settings ranging from the university to major health policy kinds of settings. The fellows are doing a great job. We have also established three programs that are likely to survive past Pew.

Clearly, a major goal of PHPP was to create a critical mass of highly trained health policy professionals. It is commonly agreed that this goal has been achieved. Carroll Estes attests to the success of the Pew programs:

I think the Pew program has very successfully seeded the field with competent well-trained scholars at government levels, nonprofit and foundation levels, and university levels. The flowering and capability of those fellows and their contributions are beginning to be recognized at fairly significant levels.

|

Clearly, a major goal of PHPP was to create a critical mass of highly trained health policy professionals. It is commonly agreed that this goal has been achieved. |

Another major goal of PHPP was to establish innovative training models that would one day stand on their own. In some cases this goal has been achieved in its entirety; in other cases it has been achieved only partially. However, a recurring theme found in all the interviews and evaluations is that the Pew program did make a difference. The Pew program has changed each institution in some way. Many aspects of the Pew program have been institutionalized, and the Pew program's ideas are standing and will continue to stand.

Linda Simoni-Wastila used a research analogy of startup funds to describe what she believes is part of Pew's legacy in health policy:

What Pew had also done was to make sure that programs like the Brandeis program and UCLA and UCSF have the programs even without funding. They all have a real strong interest in continuing programs like this through other funding sources, like AHCPR. They all continue to build this health policy arena, broadly speaking. Pew really enabled a few programs to develop educational programs in health policy and gave people fantastic skills. And now they are ongoing. It was like seed money. It's really important.... Health policy keeps on growing. Pew fostered that, and that's the legacy.

Simoni-Wastila also pointed out that although it's true that Pew succeeded in seeding the field with health policy professionals, they are not all the same type of professional. Clarifying this distinction magnifies Pew's potential impact in the health policy arena. She cited that although the Pew program has put many fellows in high-profile positions where they are able to make real contributions to the field, it has also placed with equal emphasis many background

people who do the actual research. These people build the foundation of knowledge. Pew's legacy is thus multifaceted.

One of the remarkable things that came out of the interviews was the consistency with which the faculty and fellows discussed the various issues. There was a clear consensus among those interviewed that PHPP was not only a success but is also a valuable asset to the health policy community and research.

Although there are many who worry that the programs were defunded too early, the 15-year commitment on the part of the Pew Charitable Trusts has enabled the development of the infrastructure, the institutional memory, and the invaluable training of potential mentors. As Marion Ein Lewin stated, "right now the right things are in place."

ANSWERING FUTURE NEEDS AND OFFERING ADVICE

|

The 15-year commitment on the part of the Pew Charitable Trusts has enabled the development of the infrastructure, the institutional memory, and the invaluable training of potential mentors. |

Because of the intensification of health care reform issues, health policy research is playing an increasingly vital role in generating the knowledge necessary to assist health policy makers in making informed policy decisions. There will be a continuing need to expand the supply of trained researchers schooled in health policy. Several of the schools have targeted experienced health professionals to achieve this goal. Many are also redefining the doctoral degree to make it more applicable to the current health care world. Dennis Beatrice stated that the job of training this new breed of PhDs, multi-disciplinary health policy professionals, is not yet done:

PhDs need to change because the environment needs more academic types in government. Government people can no longer shoot from the hip. The stakes are too high. We need to bring those two worlds together. We need to continue to educate, train, and out put a "different" kind of student.

In the case of postdoctoral training, both Hal Luft and Carroll Estes agree that the job is not done. They stated that there is still an environmental need for advanced training in health policy. Hal Luft reflects on the evolution of the program at UCSF and the changing environment:

When our program started there were very few integrated postdoctoral fellowship programs. I think now there are more of them, some funded by AHCPR, the RWJ Clinical Scholars, the new Johnson Policy Scholars, etc. So there are definitely more opportunities and programs for postdoctoral fellows. On the other hand I think the need for training and the demand for well-trained people has been increasing even more rapidly. I still

|

We have gone from a fragmented delivery system to a system integrated horizontally and vertically. Policy makers need to better understand how their actions affect these changes, and the organization community needs to learn more about how its members affect policy and how policy affects them. |

don't see a lot of programs that are really focused on integrating people from multiple disciplines. For instance, the Johnson Policy Scholars are for economists, political scientists, and sociologists; the AHCPR program, while broader, tends to have very few people at any one site and is often more predoctorally focused. And, there is not much integration across sites, so that they don't get enough blending. Bottom line: there is still a real need. I don't think the job is done.

In terms of the important issues plaguing the heath policy world before 1983 and the pertinent issues of today, Carroll Estes doesn't think much has changed:

We were very concerned about access, cost, and quality when we started, and we are still concerned about access, cost, and quality.

Stan Wallack thinks the need does continue to exist; however, many of the hot issues have changed to some degree. He explained that in the 1980s the issues at hand were the rapid growth of the private sector and the beginning of the emergence of managed care. This environment is no longer in its early stage. Today, the hot topics are the future of organizations and organizational change, who will survive and who will not. How will vulnerable populations fare in the new era of cost-conscious care? Wallack stated that we've gone from a fragmented delivery system to a system integrated horizontally and vertically. Policy makers need to better understand how their actions affect these changes, and the organization community needs to learn more about how its members affect policy and how policy affects them. Stan Wallack stated that the "link between policy and organization is really key" in today's world and starting a program like PHPP today would need to reflect these changes. He stated that the way that PHPP was structured was appropriate for the time:

Most traditional PhD programs are teaching methods and theory.... Health is a problem area. Health policy programs are different in the sense that they focus on the problems trying to find solutions. It's a different niche. Pew did do something different in developing people who were in that niche in the 1980s focusing on problems and their solutions. It was really appropriate for the time.

Stuart Altman agreed that there is still a need in the health policy arena for individuals who have a broad sense of what the issues are and who do not come from narrowly based disciplines. There is still a need for professionals with analytical training that allows them to think clearly and to do research. He reiterates what this document has stressed, that the prob-

lems in health care are still multidisciplinary with many dimensions and require individuals who can function effectively in this environment. Outside of the Pew programs, relatively few places in the country provide the type of training that is needed.

Steve Crane underscored Stuart Altman's and Hal Luft's point, emphasizing the importance of continuing to bring in students from different areas of the health care field. He stated that the problems of today are not oriented toward institutions, the nation, or the states; rather, they cut across all conventional boundaries and we need to continue to train people to take that view and to learn how to promote change and dialogue within the sectors.

In terms of giving advice to leaders of future programs, the Pew community had much to offer. First, having the startup money is imperative. Funds are essential to bringing the best students out of the work force and back into school where they can be ''retooled" and better prepared to deal with health care policy-related issues. Second, Carroll Estes stated that it is also essential that the leadership of the university support the program and provide the time for faculty to develop and maintain the caliber of teaching and mentoring:

I think you need an excellent faculty and a strong research program because the training has got to be hands-on with experience and supervision. I would also say how important a writing seminar would be and explicit allocation of resources to assure that there is training in writing, proposal development, and publication. It's just essential.

|

It is essential to bring the best students out of the work force and back into school where they can be "retooled" and better prepared to deal with health care policy-related issues. |

Hal Luft stated that any future program would have to think through the nature of the faculty, for the reasons mentioned above by Carroll Estes. It is important to understand the incentives to faculty and how they would benefit in the development of such a program. Hal Luft explained that the UCSF model is very faculty intensive, but that little funding is provided for faculty. Therefore, the programs have to be creative and figure out how else they can make it work. Each program will find its own solution:

Our program is a little bit like an individually designed house that was built into the side of a mountain. You really need to understand the local geology.... When you do it's wonderful, but you can't take those blueprints and use them somewhere else.

Leon Wyszewianski and Bill Weissert agreed that having up-front commitment not only from faculty but also from the institution is quintessential. They explained that a substantial investment needs to be made at the outset and that

continued investment needs to be made throughout the program.

In summary, the general consensus is that there is still a need for advanced health policy training and that the PHPP approach works well. The programs have succeeded in raising the level of acceptance for academically based health policy programs and in demonstrating their importance and value to the field.