8

Observations on the Speed of Transition in Russia: Prices and Entry

Daniel Berkowitz and David N. DeJong

INTRODUCTION

This chapter reviews two projects in which we have participated that seek to characterize the establishment and enforcement of property rights in Russia following the breakup of the Soviet Union. The first one empirically studies the extent to which price liberalization has been achieved in Russia. Price liberalization relates to property rights in the sense that when broad price controls are in effect, firms have poorly defined control rights over their cash flows, and thus cannot fully reap the benefits of ownership enjoyed in market economies. The second project makes the point theoretically that unless prospective entrants into established markets are rapidly afforded the same access to inputs and credits as existing enterprises, the right of entry is only nominal. In the case of Russia, the lack of such access effectively limits the benefits of the enforcement of property rights to firms that operated in the state network of the Soviet Union. The empirical project suggests that Russia has made admirable progress toward achieving price liberalization, despite substantial obstacles to this reform. The theoretical analysis explains fragmentary evidence suggesting that start-ups and firms operating outside the residual state

We have benefited from the comments of John McMillan, Werner Troesken, and participants in the workshop ''Economic Transformation: Institutional Change, Property Rights and Corruption," organized by the National Research Council's Task Force on Economies in Transition. We have also benefited from the comments of participants in the University of Pittsburgh's reading group on the Chinese economy. Berkowitz's research was partially supported by a Faculty Research Grant from the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, University of Pittsburgh.

system in Russia are not performing as well as their counterparts in Central and Eastern Europe.

This chapter is organized as follows. The next section contains a brief historical overview of prices and entry of private firms in the Soviet Union. Obstacles to Russia's price liberalization efforts are then discussed. The following section provides evidence that despite these obstacles, a price system integrating intra- and intercity goods markets has emerged in Russia. Data on the emerging price system, however, suggest that firms and distributors are operating with significant transaction costs. Next, we argue that new private firms in Russia face more discrimination in input and credit markets than do comparable firms in Central and Eastern Europe. Using a theoretical model, we show that the relatively slow development of competitive access to input and credit markets may explain some of the fragmentary evidence suggesting that start-ups have had a much more positive impact on the standard of living in Central and Eastern Europe than in Russia. The final section presents conclusions.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

It is clear that in the former Soviet Union, property rights were ill defined. Prices for state firms were centrally controlled, and nonstate firms (which were at times permitted to coexist marginally in certain sectors to alleviate shortages) operated in a precarious regulatory environment. The inefficiencies resulting from price controls and the arbitrary regulation of nonstate firms are well understood. The maintenance of prices at levels at which demand exceeded supply encouraged buyers in state-sector markets to allocate time to socially inefficient activities (e.g., queuing, reselling, and bribing), while the enforcement of prices at which supply exceeded demand resulted in the accumulation of excessive inventories of goods. More generally, broad price controls, coupled with artificial mechanisms designed to stimulate state firms to fulfill administratively set plans, created an economic environment in which fulfilling consumers' needs was a low priority.

Because of regulation-induced imbalances in the state sector, socialist governments were compelled to tolerate a certain amount of private business activity. As a result, private farmers furnished a large share of the urban food supply, while nonstate firms were at various times significant suppliers of clothing, handicrafts, construction services, small electronics, and repair services (see Grossman, 1977; Simes, 1975; Shlapentokh, 1989). While the prices, quality, and quantity of state-sector goods were determined according to administrative criteria, prices, quality, and quantity in the private sector were generally flexible and responsive to consumer demand. Nevertheless, state regulators and politicians curtailed private activity whenever it became too large or profitable. In periods of retrenchment from socialist reform,

private firms were often shut down, nationalized, or subjected to extortionary taxation, and many owners were fined or jailed.1 This uncertain regulatory environment led to myopic behavior in the private sector: (1) operations tended to be small and labor-intensive, (2) many private firms produced low quality goods that could be sold quickly at high prices in shortage markets;2 and (3) private entrepreneurs often simply resold goods purchased or acquired from the state sector.

PRICE LIBERALIZATION AND THE DEFINITION OF PROPERTY RIGHTS3

Price controls are no longer a major issue in the Central and Eastern European countries. These countries rapidly released the overwhelming share of state-controlled prices in their initial liberalization packages. By 1995, only 5 percent of consumer prices in the Czech Republic remained regulated, and less than 10 percent in Hungary and the Slovak Republic. In Poland, the central government continues to place price controls on utilities, medicines, and rents in public-sector housing and has an agricultural farm support program, but the overwhelming majority of prices are unregulated.4

In contrast, price liberalization in Russia has, since its inception, been a point of contention among federal, regional, and local governments. This section summarizes the evolution of price liberalization in Russia and offers several explanations for the persistence of price controls. It also argues that the persistence of controls impairs the development of the firms' ownership rights over cash flows and, more generally, that it impedes the effective establishment of property rights.

In January 1992, a federal decree liberalized the overwhelming share of state retail prices and state-administered wholesale prices. However, the prices of basic consumer goods (e.g., bread, milk and other dairy products, vegetable oil, baby foods, medicines, salt, sugar, electricity, and fuels), as well as many services (e.g., public transportation, housing rents, public utilities, and communication services) were placed under temporary controls (Koen and Phillips, 1993:4-5). At the same time, the federal government also began to curtail its subsidies to regional governments for the purchase of consumer goods.

Local responses to these federal decrees varied widely. At one end of the spectrum, many oblast (county) and city governments adjusted, or even freed, regulated prices under their jurisdiction in January and February because they could not afford to pay their own producers subsidies for charging low prices. However, at the other extreme, locally initiated price controls were rampant in 1992 and 1993. Table 8-1 presents the results of a survey of 132 Russian cities (conducted in mid-1992 and mid-1993), showing that many continued to control food prices. Many local governments also employed protectionist measures, such as issuing local moneys and ration tickets in an attempt to curtail nonresidents' purchases of the cheap goods sold in state stores. By mid-1992, 23 oblasts that had previously been net exporters of agricultural goods were reported to have set up export barriers (Koen and Phillips, 1993:11 and footnote 27). Some local authorities that had tried to keep food and other consumer prices artificially low were taking additional measures to block the outflow of these subsidized goods from their regions.

Locally initiated price controls slowed the integration of a domestic market (Gardner and Brooks, 1994). Mafia groups, often in collusion with local government officials, also limited trade between cities and curtailed the operations of some firms. Many suppliers found it difficult to sell in particular markets because local mafias demanded exorbitant rents. This situation is

TABLE 8-1 Controls on Food Prices, Mid-1992 and Mid-1993, for a Sample of 132 Russian Cities

|

Product |

Percentage of Cities Where the Price Remained Controlled Around July 1, 1992a |

Percentage of Cities Where the Price Remained Controlled Around July, 1993b |

|

Milk |

44 |

33 |

|

Kefir |

36 |

23 |

|

Fat cottage cheese |

29 |

20 |

|

Rye bread |

30 |

n.a. |

|

Mixed rye-wheat bread |

28 |

n.a. |

|

Grade I and 2 wheat bread |

32 |

48c |

|

Top-quality wheat bread |

10 |

n.a. |

|

Sugar |

30 |

14 |

|

Salt |

17 |

9 |

|

Meat products |

11 |

15 |

|

Butter |

6 |

5 |

|

Vegetable oil |

14 |

7 |

|

a Data from State Committee on Statistics (Goskomstat, 1993) for the Russian Federation. Taken from Koen and Phillips (1993:32); cited in Berkowitz (1996). b Data from Goskomstat for the Russian Federation. c This figure combines all four bread groups. n.a. = not available |

||

well illustrated by the following anecdote from the Russian press (Effron, 1994, cited in Berkowitz et al., 1996):

"It really is scary, but despite the fact that the markets are empty, it's still impossible to sell your produce" in Moscow, St. Petersburg and other large Russian cities, said Tatyana Vasilyeva, president of the local Krasnodar branch of AKKOR, which represents 16,680 private farmers. Highway robbers, traffic police who demand payola in exchange for free passage and payoffs to local gangsters make a mockery of a free market, she said. . . .

Melnik, a Krasnodar farmer, said his cooperative sent a truck load of tomatoes to Moscow, but the farmers were stopped at the outskirts of the city, where racketeers together with corrupt traffic police insisted that the contents of the truck be handed over at rock-bottom prices.

"If you do get through, they tell you what price you can sell for, and no lower," Melnik said. The complaints of beatings, threats and price-fixing have been repeated by farmers from Siberia to central Russia.

Four years after the institution of its so-called "Big Bang," the issue of price controls remains problematic in Russia. As of the beginning of 1995, the federal government retained controls on only a limited group of basic necessities and certain producer goods and services. However, communists in the federal legislature continued to lobby for the reimposition of broad price controls on food goods, domestically consumed heat and electricity, and state-owned housing (Cherkasov, 1996) that would contradict federal regulatory norms. At the same time, approximately one-third of all prices were already subject to locally initiated direct and indirect price controls (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 1995:55). In 1995, the governor of Pskov oblast and the Mayor of Moscow continued openly to regulate retail prices in their territories despite a federal edict prohibiting such controls (Borodulin, 1995). In 1993 and 1994, agricultural producer prices were 30-40 percent lower than world prices for major commodities such as grain and meat.5 Federal policies that could have sustained these low prices, such as export controls, administrative prices, and mandatory state deliveries, were not in effect in 1993-1994. As there was still significant regional dispersion in agricultural prices during this period, and many oblasts and cities openly admitted maintaining low prices for food goods, Brooks et al. (1996:Ch. 1, 7) conclude that local ". . . policies and local barriers to trade are probably among the chief constraints depressing producer prices."

Locally initiated price controls are responsible for substantive welfare losses associated with both queuing and corruption. Further, local government efforts to limit the extent of consumption by nonresidents, as well as the resale of underpriced goods, interfere with interregional trade flows. Such

protectionist measures limit the realization of potential gains from trade within the domestic market and impose real losses on consumers. In the case of China, low state-sector prices are not so problematic. Many enterprises under local jurisdiction are obligated to sell a specified amount of their final output at low and fixed state prices. As quota enforcement is generally effective, price controls in China do not result in a massive diversion of low-priced goods from basic users in the local market. However, as the analysis by Murphy et al. (1992) suggests, because quotas are poorly enforced in Russia, price controls can lead to massive diversion of goods that can be easily resold.

Why do some local governments continue to try to regulate prices? What are their incentives for maintaining policies that appear to impose tremendous local and national welfare losses?

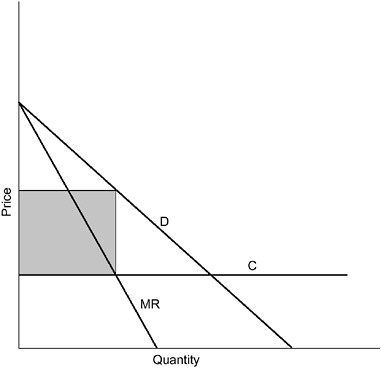

One explanation, based on an influential article by Shleifer and Vishny (1992), is that these price controls generate rents for local governments and the firms under their jurisdiction.6 The basic idea of the model is captured in Figure 8-1. Price and quantity are on the vertical and horizontal axes, respectively. The lines marked d and mr represent a local demand schedule and its corresponding marginal revenue curve, respectively. Normal costs are constant at a level c. A firm earns a "normal profit" when it charges the price c, and c therefore represents a marginal or average cost. However, c may also include per unit subsidies supplied by local or other government sources.

Shleifer and Vishny argue that price controls provide a mechanism for managers and their regulators in local governments to enrich themselves. During the transition, many firms, especially suppliers of consumer goods and services, have come under the jurisdiction of local governments. Nevertheless, the federal government is still able to impose a high tax on reported profits that exceed the normal rate. Thus, managers and their regulators in the local government can make money only if they can conceal excess profits. The spread between the posted price of c and the actual market price, multiplied by the sales quantity, represents potential "bribe revenue" that can be concealed from federal tax collectors. This is illustrated by the shaded rectangle in Figure 8-1. The posted price of c is the firm's marginal cost, which generates the normal per unit profit. The manager and local government officials equate marginal revenue with marginal cost and pocket the difference between the market and posted prices.

There are, however, two problems with using the Shleifer-Vishny model to explain locally initiated price controls. First, the federal tax rates applied to enterprises under local jurisdiction have fallen, while the local tax shares on profits, value-added taxes, and payroll taxes have increased. Thus, there is less incentive to raise money in this concealed fashion. Second, a local poli-

FIGURE 8-1 Concealed profits. See text for discussion.

tician who tries to get rich by collecting bribes in exchange for consumer goods risks alienating his/her constituents, who can vote the politician out of office in future elections.7 Such pressure to please constituents did not exist under the socialist system, when voting was an exercise designed to legitimate candidates already chosen by the local Communist Party. However, since March of 1990, deputies to the local soviets (parliaments) have had to run for office in competitive elections. Although there is some evidence of fraudulent electoral practices, survey data confirm that most elections are conducted fairly and that the new system has forced local politicians to be more accountable to their constituents (Hahn, 1994).

Even in a situation with free and fair elections, local politicians might still institute price controls if they believed they could collect bribes without being detected by their constituents. Thus, the Shleifer-Vishny model could apply to the imposition of "sneaky price controls." Local governments could charge an artificially low posted price to cover normal costs and collect monopoly rents in the form of unobserved side-payments. The persistence of low producer prices for agricultural goods and the low prices of many primary energy goods

could be evidence of the existence of sneaky price controls that allow local politicians to collect unobserved rents from exports. However, price controls on locally sold food and consumer goods could not be sneaky for very long. These goods are sold in local markets on a daily basis, and it is local constituents who must pay the posted prices and bribes. Eventually they, and others, would learn that their actions were enriching their elected politicians.

Berkowitz (1996) develops a model in which local politicians maximize constituent loyalty rather than bribes. In this model, a locally regulated state firm and an unregulated private firm compete in price, subject to capacity constraints in the local market.8 The private firm maximizes profits, while the state firm maximizes a political objective represented as a weighted sum of consumer surplus and industry profits. In this scenario, a local government will set a low price that induces rationing in the state sector when the private sector has a small capacity, and therefore can be induced to behave competitively. However, if the private sector is large enough and is able to exercise monopoly power, the local government is more likely to set a higher market-clearing price in the state sector. Thus, private capacity is a critical determinant of whether a local government sets a low rationing price or a higher market-clearing price.

The reason for this result is that private firms in a small and competitive private sector will always sell at full capacity and hence undercut any state price higher than the competitive price. Therefore, when the private sector is small and competitive, the state sector serves the public interest by setting the lowest possible state price and transferring all of the gain to its constituents. However, when the private sector is large enough to exert monopoly power, its pricing policy depends on state-sector prices. If the latter prices are high, the private sector will undercut the state firm and sell at full capacity, whereas if those prices are low, the private sector will choose the monopoly price and constrain sales to less than full capacity. While increases in state-sector prices will have a direct negative effect on the welfare of constituents shopping in state stores, a sufficiently high state-sector price will have the indirect positive effect of constraining monopolistic behavior in the private sector. When this second (indirect) effect dominates the first (direct) effect, local governments will tend to support price liberalization. This will occur in situations where the private sector is large enough to have substantial monopoly power and where state-sector technology is inefficient.

It is not possible to test the Berkowitz model rigorously, as the necessary data on private and state capacity holdings are not available. Some educated guesses about private versus state capacity holdings, however, can be made using data cited in Brooks et al. (1996:Ch. 1, Table 8-1.12). During 19911994, the share of milk procured and marketed by state organs in the Russian Federation fell minimally, from 98 to 93 percent. However, the nonstate

(private) market share of potatoes more than doubled, from 31 to 67 percent, during the same period. This suggests that private capacity is much higher for potatoes than for milk in the average local market.9 Tables 8-2a and 8-2b show that differences between private and state potato prices were, on average, very low in the Central and Volga regions of Russia from February 1992 through February 1995. On average, however, state milk prices were much lower than private prices in the Central cities of Moscow, Bryansk, Kaluga, Oryol, and Novomoskovsk and in most of the cities in the Volga region. As the survey was designed to minimize quality differentiation between state and private products, the data suggest there was a great deal of state-sector rationing in the milk market, where private capacity is small. In the potato market, where private capacity is much larger, state prices tended to be close to the market-clearing level prevalent in the private sector.

This section has argued that many local governments in Russia ignored federally mandated price liberalization. It has also suggested possible incentives for the persistence of price controls. An important question remains: Have local price controls succeeded? Specifically, has rationing persisted, and have prices failed to provide information about the demand for and supply of goods within and across cities? Alternatively, has a market price system emerged in the Russian Federation following the Big Bang of January 1992? These questions are explored in the next section.

PRICE LIBERALIZATION AND RESOURCE ALLOCATION

Working with 110 pairs of time series of state and market commodity prices in Russia (five food types across the 25 cities listed in Tables 8-2a and 8-2b, with 15 missing pairs), Berkowitz et al. (1996) study empirically the issue of whether local resistance to the federally initiated price reforms of the Big Bang has succeeded in preserving the market segmentation evident in the New Independent States, both within and across cities. Their evidence suggests that it has not. Beginning with intercity comparisons of state and market prices, they find that differences in the levels of these prices have gradually diminished, that market/state price ratios have become increasingly uniform across cities, and that the volatility of innovations to these ratios has decreased dramatically. Further, they find widespread evidence within cities that state and market prices are cointegrated, and that market prices are causally prior to state prices in the sense of Granger (1969) (see below). Finally, they find widespread evidence of cointegration and causality between state and market prices across cities.10 These findings suggest that despite the obstacles posed

TABLE 8-2a Sample Means of Private Market/State Store Relative Prices, Central Regiona

TABLE 8-2b Sample Means of Private Market/State Store Relative Prices, Volga Regiona

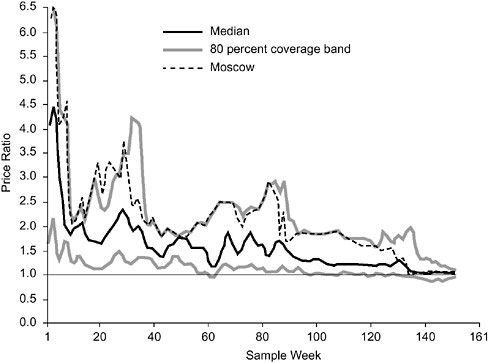

FIGURE 8-2 Market/state price ratios, vegetable oil. NOTE: The first sample was taken on February 5, 1992; the last sample was taken on February 21, 1995.

by resistant local governments, mafia activity, and inadequate infrastructure, Russia's efforts to implement economic reforms have generated tangible results: state prices have become responsive to changing market conditions, and important economic linkages are being forged across cities. The following is a brief summary of these results.

Figure 8-2 provides an overview of the distribution of the ratios of market and state prices of vegetable oil across the cities in the Berkowitz et al. sample.11 Prices were sampled approximately weekly (there were 50 observations in each year) and cover the 3-year span from February 1992 through February 1995. Four time series are plotted in the figure: the median ratio, the upper and lower bounds of the 80 percent coverage band for the ratios included in the sample, and the ratios observed for Moscow. Note that the distributions lie above unity and are skewed upwards early in the sample, but eventually contain unity; also, the median ratio falls precipitously early in the sample, and gradually thereafter. Evidently, price-subsidization activities have

faded during this period. Further, note the increasing similarity of the ratios across cities over time: the average dispersion of distributions over the last 50 observations is less than half the average over the first 100 observations. Hence local pockets of subsidization activity also seem to have faded. A final note concerning these ratios, not evident in Figure 8-2, is that they have become far more predictable over time. Using current and lagged observations of price ratios to generate one-step-ahead forecasts, Berkowitz et al. find that the variance of the errors associated with these forecasts over the first year of the sample is twice as high as the variance of the errors obtained over the entire sample; that is, state and market prices have come to exhibit far greater correspondence over time.

Berkowitz et al. also assess the dynamic interaction between state and market prices within cities, with an eye toward determining whether state prices can be viewed as responsive to changes in market conditions, as represented by innovations in market prices. They do this by testing for causality between state and market prices.12 In short, a variable (e.g., the market price of vegetable oil) is said to Granger cause another (e.g., the state price of the same product) if lagged observations of the market price can be used to improve upon forecasts of the state price obtained using only lagged observations of the state price. Evidence of this causal pattern suggests that state prices are responsive to market innovations. Evidence of the opposite pattern suggests that the state has a statistically quantifiable degree of market power over the price of this good; that is, changes in the state price generate a market response. Evidence of both patterns simultaneously is suggestive of a feedback relationship between the two prices.

Table 8-3 details the results of the Berkowitz et al. causality tests by reporting pairs of p values obtained for each city in testing the null hypothesis that the market price does not cause the state price and that the state price does not cause the market price.13 The table also includes two sets of summaries. The first is a summary column headed ''Conclusion": if the market price of a good in a particular city was found to cause the state price at a 20 percent significance level, Berkowitz et al. concluded that "market causes state"; if the opposite causal pattern was found, they concluded that "state causes market"; if causality was found to run in both directions, they concluded there was "feedback"; and if no causality was found in either direction, they concluded "no causality." Second, there is a summary statement at the bottom of the table that tallies the number of instances of each of these four possibilities

TABLE 8-3 Results of Granger Causality Tests Within Cities (commodity = vegetable oil)

obtained across cities at both the 20 and 10 percent significance levels. (In this summary, an instance of feedback would generate three tallies: one for "m causes s," one for "s causes m," and one for "feedback".)

As Table 8-3 indicates, Berkowitz et al. found evidence that "m causes s" for vegetable oil prices in 11 of the 13 cases they examined; in 8 of these cases, they also found that "s causes m," and hence concluded that there was feedback. In no case was the state price found to cause the market price exclusively; market conditions appear to be an important driving force behind changes in these prices.

Finally, the causality tests described above were repeated for state and market prices across cities to assess the strength of economic linkages among cities: evidence of causal relationships among prices across cities suggests that market disturbances are being transmitted across local borders. The causality tests were conducted for every possible combination of cities in the sample. Berkowitz et al. had data on vegetable oil for 13 cities, and hence considered 13*(13 – 1)/2 = 78 city combinations. In 69 of these combinations (78 percent), evidence of at least unidirectional causality between market prices was obtained at the 20 percent significance level; in 72 of these combinations (92 percent), similar evidence was obtained using state prices. These results indicate quite clearly the existence of statistically quantifiable economic linkages in Russia.

As noted in the previous section, producers and traders have operated in a difficult economic environment in post-Big Bang Russia. Some local governments, often in collusion with mafias, have erected export controls at borders. Thus, profitable trade has been blocked or subjected to high border taxes. Furthermore, traders and importers have had to rely on the notoriously inefficient transport sector (Holt, 1993). Private firms selling in local markets have paid high taxes to the local government, as well as protection money to local mafia groups. State firms have often been pressured by local governments to sell goods at artificially low prices. Berkowitz et al.'s evidence suggests that despite these problems, the importance of market forces in influencing state and market prices has clearly emerged following the Big Bang. It seems that traders, middlemen, and firms have succeeded in integrating city and regional markets despite very difficult circumstances.

START-UPS AND THE ENFORCEMENT OF PROPERTY RIGHTS

At the beginning of the transition, the Russian government and governments throughout the New Independent States and Eastern Europe passed laws encouraging the formation of nonstate firms and loosening administrative controls on state-owned enterprises. Implementation of legislation such as the Law on Cooperatives of 1988 in the Soviet Union, the Act on Economic Associations of 1989 in Hungary, the Law on Economic Activity of 1989 in Poland, and the Entrepreneurial Law of 1990 in the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic unleashed rapid growth in both registered upstart private and cooperative firms and transformed state-owned enterprises, which had a much stronger incentive to earn profits. Thus, a market structure emerged, especially for consumer goods and services, in which former state-owned enterprises competed for profits with an emerging private sector comprising small and medium-sized enterprises, which in many cases were new start-ups.

At this point, it is still difficult to evaluate accurately the efficiency of these emerging markets. Nevertheless, the available evidence suggests that

their performance has been mixed. For example, in the first and second years following enactment of the Law on Economic Activity in Poland, the new private sector, which comprised both new start-up firms and transformed state-owned enterprises, accounted for an impressive 11 and 19 percent, respectively, of gross domestic product. The Polish private sector continues to be a source of quality consumer goods and services in 1996. Berg (1994), Cannon (1995), and Johnson and Loveman (1994) argue that start-ups have accounted for impressive growth in gross national product per capita in Poland since 1992. Zemplinerova and Stibal (1995:251) argue that newly formed small and medium-sized enterprises—comprising start-ups, spinoffs from former state-owned enterprises, and companies formed from small-scale privatizations and restitutions—are an important reason for the impressive growth performance in the Czech Republic. Survey evidence presented by Webster (1993a, b), Webster and Swanson (1993), and Johnson (1993) suggests that start-ups have been an important supplier of high-quality goods that were in short supply under socialism.

There is scattered evidence that private entrants in Russia have not had the same impact as their counterparts in Central and Eastern Europe. A year and a half after the introduction of the Law on Cooperatives in the New Independent States, the private sector, which also comprised new start-ups and spinoffs of state-owned enterprises, provided a very small percentage of consumer goods. In a study of the market for clothing and footwear, it was found that purchases from cooperatives accounted for only 1.6 to 2.4 percent of expenditures made by workers' and employees' families. Soviet sources argue that the main reason for this is the "high prices, the unattractive appearance and the low quality of footwear and clothing provided by the cooperatives" (Shelley, 1992:318). Based on a 1992 survey of start-ups and spinoffs in St. Petersburg, Charap and Webster (1993) concluded that the contribution of these firms to market supply was limited. Anecdotal evidence in the Russian press indicates that these shortcomings persisted through 1995.

Differences in the extent to which property rights are effectively enforced are a possible reason for the variance in performance of start-up private firms in Central and Eastern Europe and the New Independent States. An entrant has well-enforced property rights when it can compete with existing firms in obtaining the inputs and credits necessary to be profitable. However, it is a well-known problem in transition economies that input and credit markets are underdeveloped. Kornai (1990, 1992:Ch. 19) argues that at the beginning of the transition, bureaucrats still retained substantial control over the overwhelming share of real and financial resources. This bureaucratic control put many start-ups at a disadvantage. For example, Hungarian firms in operation prior to the 1989 reforms had developed connections within the state sector, and therefore had privileged access to credit, capital goods, and inputs. This dense network of personal connections between bureaucrats and state managers in

newly private firms "created barriers for some newcomers who were without these connections" (Webster, 1993a: 9). In the New Independent States, firms that were offshoots of old state enterprises or had been established by local governments had preferential access to state resources (Jones, 1992:81-82). In contrast, start-ups formed after the reforms of 1988 were often forced to engage in bribery to obtain necessary goods or credit. Preliminary evidence suggests that in many sectors, market allocation has replaced bureaucratic allocation more rapidly in Central and Eastern Europe than in Russia.14 This suggests that the speed of development of input and credit markets is an important predictor of the long-run efficiency of emerging industries.

Berkowitz and Cooper (1997) analyze the speed at which bureaucratic control over credit and input markets affects the performance of start-ups and overall sectoral efficiency. They develop a dynamic model of an industry in transition in which a restructured state-owned enterprise competes with a start-up. Firms compete in quality and quantity in a differentiated duopoly. The model starts with a pretransition phase in which the state-owned enterprise is regulated by planners. At the beginning of the transition, restructuring is immediately effective, and the enterprise is forced to behave like a firm in a market economy. At the same time, a start-up that is more efficient than the state-owned enterprise is allowed to enter the market. These two firms repeatedly compete in a differentiated oligopoly.15 Initially, credit and input markets are underdeveloped and controlled by bureaucrats. These conditions increase the entrant's costs in the early rounds of competition. Over time, bureaucratic allocation is phased out, and the start-up and former state-owned enterprise have equal access to inputs and credits.

As long as costs are not too asymmetric, the underlying static model has two rankable equilibria in the long run when bureaucratic discrimination against the start-up no longer exists. In either equilibrium, there is strict product differentiation. In the efficient equilibrium, the low-cost start-up takes on the high-quality role, while in the inefficient equilibrium, the high-cost former state-owned enterprise takes on the high-quality role. Aggregate supply, product differentiation, and consumer surplus, as well as individual firm profits, are higher in the efficient equilibrium. The long-run efficiency of the transformed industry depends on which Nash equilibrium is selected.

The solution to the equilibrium selection problem is motivated by the lack of information and experience facing both transformed state-owned enterprises and start-ups at the beginning of the transition in Central and Eastern

Europe and the former Soviet Union. Start-ups entered markets in a chaotic period of rapid structural change. New firms were entering industries, old firms were operating under new incentive schemes, and laws and institutions were rapidly changing. Even the most basic sources of information, such as telephone books and transportation schedules, were often lacking (see Sheppard, 1994). The roles of firms within industries were not well defined; no firm was clearly the producer of "luxury" or "economy" goods. All of these factors imply that managers faced a significant amount of strategic uncertainty. In other words, firms made choices under a great deal of uncertainty, not only about market conditions, but also about their competitors' actions in terms of both the quantity and quality of the goods being produced.

To capture this chaotic environment, it is assumed that inexperienced managers of start-ups and former state-owned enterprises would have few guides to their opponents' likely current and future behavior other than their opponents' past behavior.16 Thus, firms are bounded rationally and use their observations of their opponents' past actions in forming expectations about their opponents' current and future strategies. This captures the feedback effects of history and initial conditions on current behavior. In a set of computer simulations, it is shown that the efficient equilibrium is always selected when there is no cost discrimination against the start-up. Furthermore, the probability of selecting the efficient equilibrium increases with the speed of bureaucratic interference in credit and input markets. The idea is that cost discrimination pushes the entrant toward a relatively low-quality role in early periods, and thus toward a low-quality role in the long run. Therefore, a startup may get stuck using a myopic strategy of supplying low-quality goods even though it would make more profits by producing higher-quality goods.

The model suggests that bureaucratic control over the allocation of inputs and credit, even though transitory, can push the market to an inefficient equilibrium in which the aggregate quantity and average quality of goods are low. Moreover, as Kornai (1990, 1992) argues, in the past bureaucrats opposed to reform have always used instances in which nonstate firms supplied low-quality goods or failed to alleviate chronic shortages as grounds for further interference with private activity. Thus at best, inefficiency means there is a loss in overall welfare, while at worst, it creates favorable conditions for the reversal of reforms. Such a reversal may occur in Russia should the Communists gain more power in the near future. The Communist leadership in Poland, however, is unlikely to harass start-ups as they have demonstrated their capacity to make a substantial contribution to raising the domestic standard of living.

CONCLUSIONS

This chapter has analyzed the evolution of prices during the transition in Russia and has drawn some comparisons with developments in Central and Eastern Europe. Evidence on progress with respect to price liberalization is generally positive: while the federal government has had difficulty in getting some local governments to comply with the federally mandated price liberalization, the statistical analysis of food markets in the Central and Volga regions conducted by Berkowitz et al. (1996) suggests that city and spatial markets rapidly integrated through a flexible price system within a short period following the Big Bang. Thus, while local governments may have had a strong incentive to interfere with the price system, many appear to be no longer willing or able to do so.

The chapter has also drawn some preliminary comparisons of the efficiency of start-ups in Russia and Central and Eastern Europe. The empirical evidence is still fragmentary (see European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 1995:Ch. 9). Nevertheless, there is evidence that start-ups in Central and Eastern Europe have made a larger contribution to domestic welfare than have start-ups in Russia. One hypothesis explaining this difference in performance is that there has been a more rapid development of mechanisms to enforce the property rights of start-ups in Central and Eastern Europe. A more rapid development of input and credit markets early on in the transition also encouraged the latter start-ups to provide higher-quality goods and achieve a higher market share than is the case for their counterparts in Russia.

REFERENCES

Åslund, A. 1985 Private Enterprise in Eastern Europe: The Non-agricultural Private Sector in Poland and the GDR, 1945-1983. London: MacMillan.

Berg, A. 1994 Does macroeconomic reform cause structural adjustment? Lessons from Poland. Journal of Comparative Economics 18:376-409.

Berkowitz, D.M. 1996 On the persistence of rationing following liberalization: A theory for economies in transition. The European Economic Review 40:1259-1279.

Berkowitz, D.M., and D.J. Cooper 1997 Start-ups and Transition. Unpublished paper, December, University of Pittsburgh.

Berkowitz, D., D.N. DeJong, and S. Husted 1996 Transition in Russia: It's Happening. Unpublished manuscript, University of Pittsburgh.

Borodulin, V. 1995 Regions' price policy. Pskov finds itself in wake of Moscow government policy. Kommersant-Daily (Russian) 25 April: 2. (Translated in EVP Press Digest, April 25).

Brooks, K., E. Krylatykh, Z. Lerman, A. Petrikov, and V. Uzun 1996 Agricultural Reform in Russia: A View from the Farm Level. World Bank Discussion Papers (preliminary version, March 1996). World Bank, Washington, DC.

Cannon, L.S. 1995 Polish mass privatization: The debate goes on. Transition 6(4):7-8.

Charap, J., and L. Webster 1993 Private manufacturing in St. Petersburg. The Economics of Transition 1(3):299-316.

Cherkasov, G. 1996 Group of deputies proposes to freeze prices. Segodnya 31 January:2. (Translated in Evnet Press Digest, February.)

de Melo, M., and G. Ofer 1994 Private Service Firms in a Transitional Economy: Findings of a Survey in St. Petersburg. World Bank Studies of Economies in Transformation, Paper Number 11. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Effron, S. 1994 Russia's breadbasket hit by mafia, marketing. Moscow Times 23(June): 12.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development 1995 Transition report. London: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Gardner, B., and K. Brooks 1994 Food prices and market integration in Russia: 1992-93. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 76:641-666.

Goodwin, B.K., T.J. Grennes, and C. McCurdy 1996 Spatial Price Dynamics and Integration in Russian Food Markets. Unpublished manuscript, North Carolina State University.

Goskomstat 1993 Rossiskaya Federatsiya v 1992. Moskva: Goskomstat.

Granger, C.W.J. 1969 Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica 37:424-438.

Grossman, G. 1977 The "second economy" of the USSR. Problems of Communism 22(5):25-40.

Gupta, S., and R. Mueller 1982 Analysing the pricing efficiency in spatial markets: Concept and application. European Review of Agricultural Economics 9:24-40.

Hahn, J.W. 1994 Reforming post-Soviet Russia: The attitudes of local politicians. Pp. 208-238 in Local Power and Post-Soviet Politics, J. Hahn and T. Friedgut, eds. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

Holt, J. 1993 Transport Strategies for the Russian Federation. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Johnson, S. 1993 Private Business in Eastern Europe. Unpublished manuscript, January, M.I.T.

Johnson, S., and G. Loveman 1994 Private sector development in Poland: Shock therapy and starting over again. Comparative Economic Studies 36:175-84.

Jones, A. 1992 Issues in the state private sector relations in the Soviet economy. Pp. 69-88 in Privatization and Entrepreneurship in Post-Socialist Countries, B. Dallago, G. Ajani, and B. Grancelli, eds. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Jones, A., and W. Moskoff 1991 Ko-ops: The Rebirth of Entrepreneurship in the Soviet Union. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Koen, V., and S. Phillips 1993 Price Liberalization in Russia: The Early Record. International Monetary Fund Occasional Paper #104, June, Washington, DC.

Kornai, J. 1990 The affinity between ownership forms and coordination mechanisms: The common experience of reform in socialist countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives 4:131 147.

1992 The Socialist System: The Political Economy of Communism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Murphy, K., A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny 1992 The transition to a market economy: Pitfalls of a partial reform. Quarterly Journal of Economics 57:889-906.

Shelley, L.I. 1992 Entrepreneurship: Some Legal and Social Problems. Pp. 307-325 in Privatization and Entrepreneurship in Post-Socialist Countries, B. Dallago, G. Ajani, and B. Grancelli, eds. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Sheppard, M. 1994 Constraints to private enterprise in the FSU: Approach and application to Russia. Ch. 14 in Russia: Creating Private Enterprises and Efficient Markets, I.W. Lieberman, J. Nellis et al., eds. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Shlapentokh, V. 1989 Private and Public Life in the Soviet Union: Changing Values in Post-Stalin Russia. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Shleifer, A., and R. Vishny 1992 Pervasive shortages under socialism. Rand Journal of Economics 23(2):237-46

1993 Corruption. Quarterly Journal of Economics 58(3):599-617.

Simes, D.K. 1975 The Soviet parallel market. Survey 23(3):42-52.

Webster, L.M. 1993a The Emergence of Private Sector Manufacturing in Hungary: A Survey of Firms. World Bank Technical Paper Number 229. World Bank, Washington, DC.

1993b The Emergence of Private Sector Manufacturing in Poland: A Survey of Firms. World Bank Technical Paper Number 237. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Webster, L.M., and J. Charap 1994 Private sector manufacturing in St. Petersburg. In Russia: Creating Private Enterprises and Efficient Markets, I.W. Lieberman, J. Nellis et al., eds. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Webster, L.M., and D. Swanson 1993 The Emergence of Private Sector Manufacturing in the Former Czech and Slovak Federal Republic: A Survey of Firms. World Bank Technical Paper Number 230. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Zemplinerova, A., and J. Stibal 1995 Evolution and efficiency of concentration in manufacturing. Pp. 233-54 in The Czech Republic and Economic Transition in Eastern Europe, J. Svejnar, ed. San Diego: Academic Press.