10

Reform of the Welfare Sector in the Post-Communist Countries: A Normative Approach

János Kornai

INTRODUCTION

Efforts are being made around the world to reform the welfare sector, or at least to debate how it should be changed.1 This process has proved difficult everywhere. In the United States, the Clinton Administration's health-care reform effort was stymied, while in Germany and Austria there has been strong resistance to attempts to introduce modest reductions of a few percentage points in welfare spending. Similar efforts in France produced crippling strikes.

Given the difficulty of the process in the rich, developed countries, one should anticipate that it will be much more so in post-communist countries, where the conditions for reform are far less favorable. The Soviet Union and the communist countries of Eastern Europe were legally committed to providing universal welfare services. These entitlements applied to every citizen and included free health care, free education (including higher education), and a state pension for every worker. In addition, the state provided enormous subsidies covering almost all basic needs (e.g., food, medicine, and housing), as well as a system of day care, kindergartens, and after-school centers that were practically free of charge. The nonstate provision of welfare services was not permitted.

The public had ambivalent feelings about the welfare sector. They took the state's extreme paternalism and their consequent material security for granted, while being critical of the generally low levels at which those services were provided. While the promise of universal entitlements aroused great expectations among the public, the actual standards for their provision embittered many, who felt that the communist state had failed to keep its promises.

As a result of the dramatic changes of 1989-1991, the post-communist countries experienced the deepest economic crises in their history. Production fell dramatically, along with household income and consumption. The purchasing power of what were already very modest monetary transfers (e.g., pensions, allowances) and the standards for services in kind (e.g., health care) deteriorated drastically. Broad segments of the population in many countries sank below the poverty line of minimum subsistence. Many post-communist economies, already suffering from serious fiscal deficits, plunged into, or were poised on the brink of, fiscal crisis. This rendered them incapable of ensuring even the minimal fulfillment of the state's previous universal commitments.

The debate about reforming the welfare state is taking place in the midst of these unpropitious circumstances. The public's sense of security, hitherto unquestioned, has been deeply shaken. Full employment and labor shortages have abruptly given way to mass, persistent unemployment. Table 10-1 shows the increase in poverty in the post-communist countries, while Table 10-2 shows changes in some key demographic and health characteristics between 1989 and 1994. Most people had expected that the pledges the communist regimes had enshrined in law, and had in fact kept, albeit at a disappointingly low level, would be redeemed by the new, democratic regimes at a higher level. The gulf between the state's commitments (and popular expectations) concerning entitlements and the extent of their fulfillment remains a source of persistent tension.

Throughout the post-communist region, welfare is the sector that has experienced the smallest degree of transformation. While the role of the state in other social and economic spheres has been narrowed or transformed considerably, in the welfare sector it remains almost as bloated as before, leaving insufficient scope for private enterprise or for freedom of choice. All the well-known features of the command economy remain: hypercentralization, rationing, and excessive bureaucratization. The chronic shortage economy that prevails in post-communist states also displays the usual symptoms: forced substitution, queuing, delays, and the resort to personal connections and corruption to side-step bureaucratic bottlenecks. At the same time, the bureaucracy that runs the state and semistate corporatist welfare sector, fearing erosion of its power, resists all reforms that point toward decentralization, competition, and the market.

TABLE 10-1 Increase in Poverty, Post-Communist Countries

|

|

1993-1995 Data |

|||||||

|

|

Poverty Headcount (in percent) |

Total Number of Poor (in millions) |

|

|||||

|

Country |

1987-88 |

1993-95 |

1987-88 |

1993-95 |

Shortfall as Percentage of the Poverty Linea |

Total Poverty Deficit as Percentage of GDP |

Elasticitya |

Type and Year of Datab |

|

Poland |

6 |

20 |

2.1 |

7.6 |

27 |

1.4 |

0.4 |

SA:I/93 |

|

Bulgaria |

2c |

15 |

0.1 |

1.3 |

26 |

1.1 |

0.3 |

A:93 |

|

Romania |

6c |

59 |

1.3 |

13.5 |

32 |

5.4 |

0.7 |

M:3/94 |

|

Balkans and Poland |

5 |

32 |

3.6 |

22.4 |

|

|||

|

Hungary |

<1 |

4 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

25 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

A:93 |

|

Czech Republic |

0 |

<1 |

0 |

0.1 |

23 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

M:1/93 |

|

Slovakia |

0 |

<1 |

0 |

0.0 |

20 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

A:93 |

|

Slovenia |

0 |

<1 |

0 |

0.0 |

31 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

A:93 |

|

Central Europe |

<1 |

2 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

25 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

|

|

Lithuania |

1 |

30 |

0.04 |

1.1 |

34 |

2.9 |

0.5 |

A:94 |

|

Latvia |

1 |

22 |

0.03 |

0.6 |

28 |

2.3 |

0.6 |

Q4:95 |

|

Estonia |

1 |

37 |

0.02 |

0.6 |

37 |

4.2 |

0.7 |

Q3:95 |

|

Baltics |

1 |

29 |

0.1 |

2.3 |

33 |

3.1 |

0.6 |

|

|

Russia |

2 |

50 |

2.2 |

74.2 |

40 |

4.2 |

0.6 |

Q2-3:93 |

|

Ukraine |

2 |

63 |

1.0 |

32.7 |

47 |

6.9 |

0.5 |

M:6/95 |

|

Belarus |

1 |

22 |

0.1 |

2.3 |

26 |

1.2 |

0.5 |

Q1:95 |

|

Moldova |

4 |

66 |

0.2 |

2.9 |

43 |

7.0 |

0.6 |

A:93 |

TABLE 10-2 Selected Demographic and Health Characteristics, Post-Communist Countries

|

Country and Year |

Crude Death Rate (deaths per 1,000 persons) |

Infant Mortality Rate (deaths in the first year per 1,000 births) |

Life Expectancy |

|

1989 |

|

||

|

Albania |

5.4 |

30.9 |

72.1 |

|

Bulgaria |

11.9 |

14.4 |

71.3 |

|

Croatia |

11.3 |

11.7 |

72.2 |

|

Czech Republic |

12.3 |

10.0 |

71.8 |

|

FYR Macedonia |

6.9 |

36.7 |

— |

|

Hungary |

13.7 |

15.7 |

69.6 |

|

Lithuania |

10.3 |

10.7 |

68.7 |

|

Poland |

10.0 |

16.0 |

71.1 |

|

Romania |

10.7 |

26.9 |

69.6 |

|

Russia |

10.7 |

18.1 |

69.6 |

|

Slovakia |

10.2 |

13.5 |

71.1 |

|

Slovenia |

9.3 |

8.1 |

72.8 |

|

Turkmenistan |

7.7 |

54.7 |

65.1 |

|

Ukraine |

11.7 |

13.0 |

70.9 |

|

1994 |

|||

|

Albania |

5.25a |

35.7 |

73.7a |

|

Bulgaria |

13.2 |

16.3 |

70.9 |

|

Croatia |

10.4 |

10.2 |

73.1 |

|

Czech Republica |

11.4 |

8.5 |

72.9 |

|

FYR Macedonia |

8.1 |

27.3a |

— |

|

Hungary |

14.3 |

11.6 |

69.4 |

|

Lithuania |

12.5 |

16.5 |

68.7 |

|

Poland |

10.2a |

13.3a |

71.7a |

|

Romania |

11.7 |

23.9 |

69.5a |

|

Russia |

15.6 |

18.6 |

64.1 |

|

Slovakia |

9.6 |

11.2 |

— |

|

Slovenia |

9.7 |

6.5 |

74.1 |

|

Turkmenistan |

7.9 |

42.9 |

63.9 |

|

Ukraine |

14.7 |

14.3 |

68.4 |

|

Central and Eastern |

|

|

|

|

Europe averagea |

11.4 |

14.4 |

71.1 |

|

Former Soviet Union averagea |

13.1 |

23.5 |

66.1 |

|

European Union averagea |

10.1 |

6.79 |

76.9 |

|

a The data are for 1993. SOURCE: Goldstein et al. (1996:10). |

|||

Where can the post-communist states look for a model of an efficient welfare state? Every welfare state—without exception, in the most developed and moderate-income countries alike—operates dysfunctionally and faces current or potential crises. The post-communist countries will therefore have to undertake for themselves the design of the kind of welfare sector they need.

We must recognize that the debate on welfare reform in the post-communist states is in a shambles. It is taking place on various planes: among politicians, within and between political parties, between finance ministries and the ministries responsible for managing the welfare sector, among opposing pressure groups, and among various schools of thought in the academic world. Reforms too often reflect compromises between diametrically opposed principles, or embody no guiding principle whatsoever.

This chapter seeks to contribute to the debate by clarifying the principles on which the reform of the welfare sector should rest. In so doing it explicitly adopts a normative approach to the problem. A rigorous, axiomatic discussion is not undertaken here. Although such a discussion would reveal that the principles presented in the chapter are logically interrelated and form a coherent theoretical structure, the present argument is developed at a lower level of abstraction. Nevertheless, it offers an intellectual and ethical compass and should help transfer the debate to matters of principle. The discussion begins by setting forth some ethical postulates that form an essential basis for the reform effort. It then presents a number of desirable attributes for the new welfare institutions and coordinating mechanisms. This is followed by a discussion of the desirable proportions of welfare allocation. The final section provides concluding remarks.

ETHICAL POSTULATES

Although I am an economist, I do not base my argument here on economic principles, or advocate reform because the welfare sector is too costly or cannot be financed over the long run. Rather, this study embodies a set of ethical principles. It is addressed to "the reformer," be that a politician, government official, expert adviser, union official, or academic. Each principle should be understood as a memento —something to keep in mind when proposing a reform. These principles also represent a credo—the set of values I espouse and that underlie the proposals developed here. Economic principles are considered later, but they are not treated here as the foundation for reform. This discussion attempts to provide "minimalist" solutions, in other words, to stipulate only the minimum requirements—that which is necessary and sufficient as an ethical starting point for welfare reform. The institutional attributes and allocative proportions presented in later sections should flow from these moral imperatives.

Principle 1—The sovereignty of the individual: Reforms should maximize the sphere within which individuals make decisions. The state's sphere should be correspondingly curtailed.

The main problem with the welfare system inherited from the communist regime is that it leaves too wide a sphere of action, and a corresponding range of resources, in the hands of the government, the political process, and the bureaucracy, rather than with the individual. This infringes on such fundamental human rights as individual sovereignty, self-realization, and self-determination.2 When government spending on welfare decreases, along with the taxes that finance it, citizens are not having their rights infringed upon; rather, they are regaining rights of individual determination and disposal.

Principle 1 not only ensures the individual's right to make his/her own decisions, but also requires that individuals be responsible for their own lives. They must give up the habit of having the paternalist state think for them, and must be assisted by reformers in this "detoxification." Implementing this principle gives citizens broader rights to choose, but they must recognize that they will also be responsible for their choices and bear the consequences. The workshop for which this study was originally commissioned was held in the United States, where this is considered a trivial requirement, ingrained in all citizens. However, for generations that came to maturity under the communist system, a different principle was instilled: that the ruling party-state was responsible for everything, and that individuals should accept its decisions, trusting that they were in capable hands. Since the state provided for any unforeseen eventualities (e.g., illness, disability, death of the breadwinner), there was no need to prepare for the uncertainties of tomorrow.3 The reform of the welfare state must be based on the development of a new ethos that emphasizes the sovereignty and responsibility of the individual.

No society can function without some amount of government coercion, but it follows from Principle 1 that this should be reduced to a minimum, while individual, voluntary action should be expanded wherever possible. Whereas paternalism attempts to force people to be happy, people should be allowed to prosper or fail on their own.

Principle 2—Solidarity: Help should be provided to the suffering, the troubled, and the disadvantaged.

Many religions, including the Judeo-Christian and Buddhist ethics, call for compassionate solidarity, as do many labor movements and people on the left of the political spectrum. These sentiments also arise out of ordinary human goodwill, a sense of fraternity and community, and an innate altruism, without necessarily being based on any specific world view or intellectual tradition.

The solidarity principle suggests that apart from individual and collective charitable work, communities should help the suffering, troubled, and disadvantaged through a system of state redistribution. We need not explore here the criteria for receiving state assistance. Suffice it to say that the set of those in need of aid will be much narrower than the community as a whole (see Andorka et al., 1994; Atkinson and Micklewright, 1992; Milanovic, 1997; Sipos, 1994).

Implementation of the solidarity principle requires only targeted state assistance, not universal entitlements. This means benefits need not be awarded as a citizen's right to both the rich and the poor, the needy and the self-sufficient. Principle 2 neither requires nor excludes universal state commitments. Universal entitlements do not conflict with moral imperatives, but with economic realities. More will be said about this later, under Principles 8 and 9.

Principle 2 conflicts with political rhetoric that seeks to turn the middle class into the main beneficiary of tax policy and redistribution. The middle class, by definition, is not the social stratum in the greatest need of assistance. Under the communist system, much of the state's redistributive largesse went to the middle class, as it does in many parts of the world. Principle 2 calls for assistance only to those who are truly in need.

Principle 2 also requires that every member of a community be able to satisfy his or her basic needs. This does not imply that the state must provide for these needs, either gratis or in the form of preferential benefits for everyone. The principle of solidarity applies only to those who are incapable of supplying their basic needs through their own efforts.

In the light of Principle 2, it is worth considering the issue of uncertainty. Although one may not be dependent on others at present, one may become so in the future. According to Principle 1, the individual must prepare for such contingencies by saving and building up reserves or by purchasing a private insurance policy. Individuals should be entitled to state assistance on a solidarity basis only if they encounter problems for which they could not reasonably have been expected to prepare.

Principle 2 includes solidarity between generations, which requires an equitable intergenerational distribution of life's burdens (see also Ferge, in this volume). The present generation must show solidarity with future generations; there is no moral law that justifies making life easier today by encumbering future generations with grave debts. To do so creates an economic time-bomb that may explode in the future. An example is pension debt, which is likely to reach unsustainable levels in many countries (see Fox, in this

volume). Hungary's 1994 pension debt, for instance, was equivalent to 263 percent of its gross domestic product (World Bank, 1995a:36, 1995b: 127).

Principle 2 also requires that every citizen be given an opportunity for self-fulfillment. This is one argument (along with substantial external utility) underpinning state support for public education. In this connection, solidarity can justify "affirmative action," i.e., assistance that compensates the disadvantaged in order to ensure equal opportunity. It cannot, however, be used to justify any kind of crude, artificial attempt to level the great differences that exist among people.

Principle 2 must be applied in conjunction with Principle 1. Most people find "alms" demeaning. The needy must be helped primarily by being given a chance to work and undertake useful activity. The degree to which claimants are capable of helping themselves and adapting to their situation must be considered when the degree and type of help are determined.

Principles 1 and 2 must also be taken into account with respect to compulsory insurance. All citizens should be legally obliged to purchase minimum levels of pension and health insurance. Such policies could be held by decentralized insurance institutions. Although this obligation restricts the application of Principle 1 (voluntary action is preempted by a legal requirement), it should not be seen as paternalism or an attempt to impose happiness. The motive here is collective self-interest, not altruism. Humane societies will feel compelled to care for the sick who are bereft of treatment or the penniless elderly, and they will do so at the taxpayers' expense. To avoid this undesirable external effect, the law must oblige all citizens to obtain at least minimal levels of insurance coverage (Lindbeck and Weibull, 1987). Principle 2 should be brought into play only on behalf of those who are unable to afford even minimal insurance.

The differences between this proposal and the schemes presently in operation in the post-communist world are obvious. The former requires citizens to maintain minimum levels of insurance (with the possibility of adding supplementary insurance voluntarily) and targets state assistance to the needy, while the latter promises universal entitlements, with resources channeled through paternalist state redistributive institutions.

One further comment seems appropriate. This study does not embody a discussion of the ultimate values of freedom, equality, well-being, or social justice, or of the relationship between those ultimate values and particular social institutions. These are the concerns of political theory and deal with the ethical foundations of the "good" society.4 The discussion here does not

attempt to contribute to the analysis of these more profound issues. Principles 1 and 2 deal with what might be termed "intermediate" ethical requirements, not ultimate values. These requirements can provide a broad base that is acceptable to people with widely differing views on the nature of freedom, equality, and social justice. Still, Principle 1 will be alien, and Principle 2 may be superfluous, to those whose axiomatic point of departure is collectivist, i.e., those who would subordinate the rights of the individual to the interests of a specific community or ideology, be that a nation, race, class, or religion.

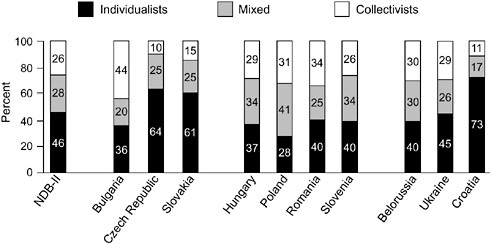

A 1992 survey conducted under the aegis of Richard Rose's "New Democracies" project (Rose and Haerpfer, 1993) yielded findings that shed light on the issue of individualism versus collectivism. On the basis of replies to four questions, analysts ranked respondents' viewpoints as approximating individualist or collectivist views of the world. The results are shown in Figure 10-1. In every country, with the exception of Bulgaria and Poland, more people were inclined to take an individualist rather than a collectivist approach, and in three countries, fully two-thirds of the population favored individualist ideas. The proportion of ambivalent positions is also significant. Although there are some differences between the definitions used in that survey and those used here, it is remarkable that ideas of individual sovereignty and responsibility play such an important role in the value systems of considerable segments of the population throughout the post-communist region.

FIGURE 10-1 Individualist versus collectivist world views. NOTE: The respondents had to choose between an "individualist" and a "collectivist" alternative concerning four issues. The responses were coded as follows: individualists, three or four individualist preferences; mixed, two individualist and two collectivist preferences; collectivist, three or four collectivist preferences. SOURCE: Rose and Haerpfer (1993:71). Reprinted with permission.

DESIRABLE ATTRIBUTES OF INSTITUTIONS AND COORDINATION MECHANISMS

Let us now turn to another plane of reform. The process of reform eliminates or alters old institutions and coordination mechanisms—the rules of the game—and establishes new ones. Principles 3 to 7 concern key attributes of these institutions and coordination mechanisms.

Principle 3—Competition: There must be competition among different ownership forms and coordination mechanisms. The almost total monopoly of state ownership and control must cease.

Principle 3 does not prescribe quantitative proportions between state and nonstate institutions. However, the nonstate sector must attain a critical mass before it can overcome the enervating effect of the state's dominance, which enables the producer (the welfare state) to dictate to the consumer. Although considerations of efficiency argue in favor of competition (see Principle 4), the main source from which Principle 3 is derived is Principle 1. There must be competition in order for citizens to be able to make choices. If they do not like what they receive from the state, they can go elsewhere.

The survival of the previous system in the welfare sector leaves citizens defenseless in a number of important areas, even though decisions originate with more diffuse "state authorities" rather than the politburo. Decisions as to which resources will go to medical care or what income the elderly will receive depend on the squabbling of political parties, which subordinate policy positions to their rivalry for popularity, and the relative strength of different lobbies and groups of bureaucrats, which reach compromises behind the scenes. Principle 3 seeks to place a much larger proportion of decisions on these matters in the hands of the persons directly concerned. At least for a sizable portion of these expenditures, people should decide individually what they want to spend on their health and that of their families and how they want to prepare for their old age. Such choices will become available when at least a fraction of total welfare resources ceases to be subject to state allocation, and households and individuals are able to decide on their use through market mechanisms.

Principle 3 seeks to open up all aspects of the welfare sector to private for-profit and nonprofit enterprise. It would be useful for private hospitals, clinics, laboratories, kindergartens, and retirement homes to emerge on a broad scale, through either the founding of new organizations or the privatization of those currently in the hands of the state. Commercial insurance companies and nonprofit organizations should be encouraged to expand into pension plans and medical insurance as well. The function of applying Principle 2 (solidarity) could be shared among the state, nonprofit organizations, and the for-profit segment of the welfare sector.

TABLE 10-3 The Real Value of Pensions in the Czech Republic and Hungary (as percentage of 1990 value)

|

Country |

1991 |

1992 |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

|

Czech Republic |

82.9 |

81.2 |

76.9 |

77.5 |

82.2 |

|

Hungary |

92.4 |

87.8 |

84.6 |

86.5 |

77.4 |

|

SOURCE: For Czech Republic, Klimentová (1996:Chart 3); for Hungary, Figyelõ, July 11, 1996. |

|||||

Those who insist on the complete nationalization of the welfare sector argue that the public demands security and that only the state can provide it. Yet both sophisticated analyses of uncertainty and common sense suggest a simple rule: do not put all your eggs in one basket. In investment-portfolio terms, people should diversify. Just as it would be a mistake to entrust all of one's retirement savings to a single pension fund, total reliance on the state can render an individual vulnerable. By the time a person retires, the political authorities may have revised the rules for compensation, effectively expropriating part or all of an individual's contributions.5 Alternatively, pensions may be eroded by policy-induced inflation and by indexation rules that whittle away their real value (see Table 10-3). Thus, the most expedient proposals for pension reform are those that rest on several pillars, allowing different pension schemes to be used concurrently (see Fox, in this volume). Similar "multipillar" solutions will be needed to fund the health service and other elements of the welfare sector.

Principle 1 suggests that citizens should not be forced into any particular scheme; to the extent possible, they should be able to choose for themselves. A "menu" of various forms of ownership and mechanisms of control and coordination should be developed from which citizens can choose. They should be able to learn from their own and others' experience, to experiment, and to modify their points of view. This is one more reason why competition is needed in the welfare sector. In the presence of competition, selection can be made not only through the friction-ridden political process, but also directly, through the market choices of households and individuals.

Principle 4—Incentives for efficiency: There must be incentives for forms of ownership and control that encourage efficiency.

This principle is so self-evident that it scarcely need be argued. The only reason for including it among our declared principles is that it tends to be

forgotten by politicians and academics who defend the status quo in the welfare sector.

Incentives for efficiency (and this is a substantial departure from previous practice) must be provided on the demand side as well, to the recipients of welfare services. This means that with only the rarest possible exceptions, services should not be free. Rather than state subsidies forcing prices down below market levels, state assistance should be targeted (by vouchers, for example) to those for whom it is justified (normally this would mean those in need, in line with the principle of solidarity). Even if the state or the insurer covers most of the cost, recipients should contribute a copayment so that they recognize the service is not free.

Proper incentives on the demand side include inducing efficiency among the insurers that will largely finance welfare services. This is one of several arguments against awarding monopolies to the monstrous "great wens" of central state health insurance and pension authorities. Without competition, there cannot be sufficient incentives for efficiency and thrift.

The same argument applies on the supply side, to the organizations that provide welfare services. Just as the sovereignty of the individual argues for competition, no one should be left at the mercy of a single monopolistic organization. Competition can be useful in other ways, too, by encouraging improvements in quality, the development of new technology, the discovery and introduction of new scientific advances, and the reduction of costs.6

Another aspect of incentives and efficiency is the most expedient form in which to accumulate and utilize "welfare reserves." Two pure cases can be distinguished. The first applied most consistently under the communist system, where all welfare services were provided on a nationalized, "pay-as-you-go" principle. Households were not expected to save for security purposes; instead they were forced to pay the taxes that financed both welfare services and investment. Total centralization led to low efficiency, both in the sphere of welfare provision and in the selection and implementation of investment projects.

The opposite case is one in which the accumulation of reserves is left entirely to households and individuals. Each decision-making unit places its reserves in a portfolio with several different components, allocating some to bank deposits or mutual funds and paying premiums to insurance companies and pension funds. The financial sector, i.e., the credit and capital markets, in turn uses this huge stock of savings to finance investment in a decentralized fashion.

These two cases demonstrate the extremes of perfectly centralized and perfectly decentralized capital allocation mechanisms. While the decentralized mechanism has many advantages, we can reasonably suppose that some public investment will still need to be financed out of taxation (e.g., for infrastructure investments or other public goods). One conclusion, however, has clearly emerged from the great historic contest between the communist and capitalist systems: a system in which decentralized investment based on private ownership and competition predominates is more efficient than one in which centralization and state ownership prevail.

The pool of savings for illness, unemployment, accident, or old age will form such a vast proportion of total savings that it should not be handed over to a state bureaucracy. The bulk of these savings should be employed in a decentralized way. Following this line of argument to its logical conclusion, Principle 4, increasing incentives for efficiency, provides a further weighty argument in favor of Principle 3, the expansion of competition and nonstate institutions.

Principle 5—A new role for the state: The main functions of the state in the welfare sector must be to supply a legal framework, to supervise nonstate institutions, and to provide ''ultimate" or last-resort insurance and aid. The state must also be responsible for ensuring that every citizen has access to basic education and health care.

To argue about whether the state should have a large or a small role, or whether it should remain in or withdraw from the welfare sector, is to engage in a sterile debate. The essential requirement is that the state must be radically transformed. Let us briefly review the functions of a reformed state in the welfare sector:

-

The state should establish the legal framework within which institutions in the welfare sector will operate. Citizens must be able to seek redress from the courts when their rights are infringed by the state, insurers, hospitals, or other service providers.

-

The state should create supervisory bodies for monitoring the operation of institutions in the welfare sector. It should establish minimum standards for service providers, while claimants' and users' associations, the press, and civil society as a whole should play the role of watchdogs.

-

The state should guarantee the security of savings that citizens entrust to insurance institutions or pension funds.7

-

The state must ensure every citizen's access to basic education and health care. Declaring this to be a state responsibility still leaves open the question of how it is to be fulfilled and through what kind of institutions. It neither requires nor precludes the possibility that institutions owned or controlled by the state will take part in providing or financing these services.

-

Nonstate organizations should have a role in applying the principle of solidarity. Nonetheless, there is no way the state can avoid making a substantial contribution. This should not be hidden as state assistance to those in need or subsumed under other public expenditures so the voters do not notice.8 It needs to be stated openly.

It should be clear from what has been said that this study does not advance a purely laissez faire program. It does not seek to relieve the state of all responsibility for the welfare sector. Even if most tasks are to be performed by private (for-profit or nonprofit) enterprises, and these organizations are to be coordinated mainly by market mechanisms and spurred on by competition, this must take place under rules written by the state and under the state's (and civil society's) supervision. The state must also contribute economic resources when there is an inescapable need for it to do so. Various instances of "market failure" have been sufficiently clarified by economists. The state is justified in intervening in cases where the market has failed, provided there is no reason to fear that state activity will cause even greater failure (see Buchanan and Tullock, 1962; Niskanen, 1971; Tullock, 1965).

However, in many cases it is difficult to gauge the relative prospects for these two kinds of failure. That is one reason this study leaves open the question of how large the segment of the welfare sector that is under either state ownership or direct state control should be. If the public, through the political process, expresses the wish that part of the financial provision for old age remain within the state pension system or that certain hospitals remain in state hands, and if they are willing to pay the necessary taxes, their wishes should be respected. The latter proviso (willingness to pay the associated tax burden) leads us to the next principle.

Principle 6—Transparency: The relation between the state's provision of welfare services and the tax burden that finances it must be made manifest to citizens. Practical reform measures must be preceded by open and informed public debate. Politicians and political parties must openly declare what their welfare-sector policies are and how they will be financed.

This principle has three parts. The first calls attention to the fact that many citizens do not recognize that the costs of the services provided by the welfare state are borne by them, as taxpayers. Understanding of the relationship between taxes and state spending is vague or distorted all over the world, but this fiscal illusion is nowhere as pronounced as it is in post-communist societies, where people have been indoctrinated for decades with the idea that health care or education is "free."9 Once citizens recognize that the taxpayer pays for every state service and are informed of the extent of the costs, resistance to decentralizing reforms will decrease substantially. Citizens must learn that the political process gives them a choice as to the method of payment, both for the welfare sector as a whole and for its individual components (pensions, health care, child care, and other social benefits). They can pay either through taxes (payments to the state, which then allocates money for welfare services in the budget) or through direct purchases (e.g., pay for service or insurance premiums paid by the household to the insurer who pays for the welfare service).

There is also considerable debate about the manner in which democratically elected parliaments and governments should consult public opinion in advance of introducing reforms—especially the opinion of groups directly affected by those measures. The answer will depend on several factors, one of which is whether the situation requires urgent action. Reform of the welfare sector will not be accomplished by a single, sweeping reform. It is not designed to avert economic catastrophe or respond to an acute crisis. It entails reshaping the nature of the society and the relations between individuals and the state, and it will take place over a long period of time. That is why the second part of Principle 6 calls for public debate on these weighty reform proposals and with broad dissemination of the requisite information.

This leads to the third part of Principle 6, the requirement for transparency in political debate. Political parties rarely put their ideas on welfare reform squarely before the voters, either because they have not thought their proposals through sufficiently or because they prefer to conceal their intentions. This study, in line with its normative character, does not investigate why this is so; rather it advances an ethical requirement that is addressed to the better side of every politician. It demands honesty with the voters, telling them frankly what one intends to do about pensions, health care, and other welfare services. It is also addressed to others, particularly academics researching this subject. We have no interest in gaining popularity; we are not running for elected office. We have a duty to discover and demonstrate the benefits and social costs of alternative welfare-sector proposals. Finally, this principle is addressed to

citizens. It calls upon them to discern, from the statements of politicians and the programs of political parties, their real intentions with respect to welfare reform, and to bear these in mind when voting.

It is worth acknowledging that it is frequently difficult to apprehend accurately a party's or a candidate's intentions, and that it is also difficult to decide how to vote. In casting their votes, citizens must choose between "packages" of policies. A voter may choose to vote for candidate A rather than B, even though B's welfare policies are more attractive, because he or she prefers A's economic, judicial, foreign, or other policies. Suffice it to say that it would exceed the scope of this study to discuss how far this problem might be resolved by a system of referenda on important legislation. With few exceptions, democratic constitutions permit referenda only in special circumstances.

These difficulties provide additional arguments for Principles 1, 3, and 5. There must be a reduction in the set of welfare services under the state's direct control so that these matters are less subject to the vagaries of the political process.

Principle 7—Time: There must be sufficient time for the new institutions of the welfare sector to evolve and for citizens to adapt.

The reformed welfare sector will contain institutions that were unknown under the communist system. Some will be entirely new, such as newly established private clinics, hospitals, and nonstate pension funds. Others will develop out of formerly state-owned organizations; for example, a team of doctors might open a surgery in a public hospital under a rental contract. In my view, the advocates of reform cannot leave these developments entirely to spontaneous processes, for many reasons. The creation of new institutions and the transformation of old ones requires the careful design of new rules, which must be enacted by legislation or as the by-laws of organizations. Some new organizations will emerge at the initiative of governmental agencies, while in other cases political pressure will be needed to set the process of change in motion. One might add that by definition, a change in the role of the welfare state can occur only with the state's involvement. In sum, while many components of the evolutionary process of institutional transformation will happen spontaneously, this study does not advocate a reform pattern that relies exclusively on spontaneous changes (Davis and North, 1971; North, 1990).

Neither does this study advocate forcing through the fastest possible reform of the welfare state at any price. There are situations of crisis in which a government is compelled to enforce a painful and unpopular economic adjustment program. Such a program may have to include measures that cause a rapid fall in state welfare spending. That is one thing, and comprehensive reform of the welfare sector is another. Comprehensive reform is not fiscal fire fighting, but a radical social transformation that must not be conducted at

breakneck speed. Sufficient time must be allowed for programs to be carefully drafted and political support to be mobilized.

The issue of political support was mentioned under Principle 6. The more thoroughly the public understands both the social costs and the likely benefits of reform, the readier it will be to support the reform. If at all possible, time must be allowed for citizens to adapt to the new situation. The problem of differing degrees of adaptability was mentioned under Principle 2. Reformers must display calm insight and compassionate understanding of the fact that people have different powers of adjustment. To illustrate this, let us consider the example of transforming the pension system.

The younger generation can justifiably be called upon to accept radical changes. Their whole active working life lies before them. Let them, and their employers, pay the sums needed for retirement into individual accounts and entrust these to pension funds that will put them to good use. In due course, they will receive pensions that represent the fruits of their own efforts and savings. In line with Principle 1, there should be a close connection among earnings, propensity to save, and retirement income, spanning the whole life cycle.10

The same cannot be said to those who are already receiving pensions. In their case, the state must fulfill the obligations undertaken by previous governments (see Kornai, 1996). They are no longer capable of adapting to a new pension system. Apart from the fact that the state is legally required to meet these obligations, Principle 2, the principle of solidarity, dictates that society must continue to maintain the "pay-as-you-go" system, whereby the active members of the labor force pay taxes that finance state pensions.

As for the intermediate generations, I would propose that they be given a choice. They could leave their accrued pension entitlement with the state, or, if they so chose, could transfer it (after the deduction of reasonable conversion costs) to an individual account with a nonstate pension fund.

Returning to the more general plane of discussion, to the extent allowed by the state of the economy, the sufferings caused by the introduction of these changes should be mitigated, and the process of adaptation encouraged, through assistance to those who suffer severe losses as a result of reform. Long-term assistance should be given, however, only to those who are really unable to adapt. For everyone else, assistance should be granted only for a temporary period. Individuals should have a grace period, but they must recognize that they will have to adapt to the new situation once that period is over.

DESIRABLE PROPORTIONS OF ALLOCATION

Principle 8—Harmonious growth: There must be harmonious proportions between the resources devoted to investments that directly promote rapid growth and those spent on the welfare sector.

Two extreme views are often heard in the welfare debate. One places a one-sided emphasis on the losses entailed in the transition and fails to acknowledge that the best way to overcome present difficulties is by encouraging the long-term growth of the economy. However trivial this may seem to an economist, it is consistently ignored by those who favor maintaining the welfare-state status quo. They dismiss the elementary economic argument that living standards for the majority in the post-communist countries will never attain the present average level in the West until there is sufficient investment to produce lasting and sufficiently rapid growth.

At the other extreme is the view that sacrifices welfare spending in favor of investment projects. Statistical examinations covering several countries show that in the long term, the fastest growth has taken place in the Southeast Asian countries that spend least on welfare provisions. The authors either leave Eastern European readers to draw their own conclusions, or state plainly that if they want to catch up with the West, they should follow the Southeast Asian model.

To me, as a member of the older generation, this emphasis on very rapid growth sounds familiar. One of the watchwords of the Stalinist-Khrushchevite economic policy was, "Let us catch up with the West as soon as possible." This view led to a forced growth strategy and consequent distortions in the economic structure, a key result of which was that people's immediate welfare needs were ignored (Kornai, 1972). This bias created grave problems within the socialist system, the consequences of which have yet to be overcome. It would be a shame to repeat this failed strategy.

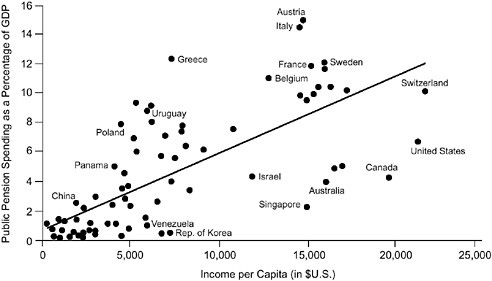

A different conclusion is reached if the international comparison is based not on the relation between aggregate welfare spending and rate of growth, but on that between aggregate welfare spending and level of economic development. As a country develops, state spending on health, education, culture, child care, and the elderly increases. The connection is not deterministic, since it is affected by other factors as well, including the political complexion of the government and cultural traditions. Still, there is a close correlation between overall economic development and government spending on welfare. This correlation is demonstrated in Figure 10-2 and Table 10-4.

Departure from the most desirable proportion between government welfare expenditure and level of development might occur in two directions: too much or too little spending. As an "overcompensation" for the excesses of

FIGURE 10-2 Relation between income per capita and public pension spending.

NOTE: The sample comprises 92 countries for various years between 1986 and 1992; because of space limitations, not all data points are identified.

SOURCE: World Bank (1994:42). Reprinted with permission.

the Stalinist period, some post-Stalinist countries let welfare spending run rampant. Prompted by the paternalist ideology and a desire to calm the population, the state undertook greater obligations than its resources warranted. Some Eastern European countries, especially Hungary, overreached themselves not only in state obligations, but also in the fulfillment of those obligations. That is why I termed them "premature welfare states" in an earlier study (Kornai, 1992). Hungary went the furthest in this respect (see Table 10-5).

There is a vital need to restore the proper balance by approaching the problem simultaneously from two directions: state commitments and entitlements must be reduced while economic growth is promoted.

For my part, I would not venture to advance a quantitative golden rule that would ensure harmonious proportions. It would be an exciting research task to reconsider this issue in the context of the post-communist transformation. However, although Principle 8 may not supply a method of quantification, it certainly contains a warning against allowing blatant distortions and heeding false political slogans.

Here I must refer back to Principle 1. One reason why more economic choice has to be entrusted to individuals is the well-founded doubt that central planners will make the best decisions. Is it necessary for the state to intervene in defense of health care and educational expenditures? Must households be

TABLE 10-4 Public Pension Spending

TABLE 10-5 Composition of Public Social Expenditures in Hungary and in Selected OECD Countries (as percentage of GDP)

|

Hungary 1992 |

Germany 1990 |

Spain 1989 |

Sweden 1991 |

|

|

Pensions |

10.4 |

9.6 |

7.9 |

13.2 |

|

Healtha |

5.3 |

9.1 |

6.5 |

8.8 |

|

Family |

3.9 |

1.3 |

0.1 |

1.4 |

|

Housing |

2.8 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

|

Unemployment |

2.3 |

2.1 |

3.1 |

4.1 |

|

Total |

24.7 |

22.3 |

16.3 |

26.4 |

|

NOTE: Pensions include old age, disability, and survivors. Unemployment includes all active programs and unemployment compensation. a Refers to 1991 and only to public-sector expenditures on health. SOURCE: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (1995:49). |

||||

prevented from investing too much on building factories, for instance? I hardly think there is a danger of that. On the contrary, one might expect that, through a myriad of individual decisions aggregated on a national level, society will spend more on health, education, and other welfare activities than central planners would. One sound argument for intervention, however, is the fear that without a certain measure of redistribution, guided by the solidarity criteria of Principle 2, an extremely decentralized decision-making process might fail to provide the lowest, most disadvantaged strata of society with basic welfare benefits.

Principle 9—Sustainable financing: The state budget must be capable at all times of financing the state's obligations.

While Principle 8 concerns the desirable allocation of real resources, Principle 9 draws attention to the financial aspect of this issue. However self-evident this requirement may seem, its infringement was what brought an end to the previously "untouchable" status of popular welfare programs in many parts of the world.

Many economies have substantial budget deficits; this is true for the post-communist countries almost without exception. Where a budgetary system clearly earmarks revenues for specific welfare expenditures, the financial deficits incurred by individual components of the welfare sector can be discerned, at least in part. In many countries, however, the funds required to defray welfare services are not separated from those for other expenditures. State welfare expenditures are paid out of general tax revenues, making it difficult to determine the relative role of welfare spending in the overall deficit.

This study does not address the various causes of fiscal deficits at different times and in different countries. Nonetheless, it is worth drawing attention to the fact that the welfare commitments entrenched throughout the developed world are likely to become unsustainable sooner or later, other circumstances being equal, and taking into account the most likely economic growth rates and demographic trends. In particular, state pension systems are threatened everywhere by fiscal crisis. State health services are also imperiled by increasing pressures from the demand side, and it appears that they will eventually become unsustainable as well. The severity of this crisis varies from country to country, with experts predicting that these systems will reach their financing limits at different dates and questioning whether the gap can be bridged by raising taxes.

But raising taxes generates other issues. In economic terms, higher taxes will dampen incentives and impede investment. Politically, the unpopularity of tax increases must be weighed against the unfavorable impact of reduced welfare spending. Ultimately, it appears that in most post-communist coun-

tries, the need to improve the fiscal balance will force reductions in state welfare spending.

Although I have left Principles 8 and 9 to the end of this discussion, they are no less cogent than the other principles. We must consider both the social and economic costs and benefits of welfare reform. All too often the academic debate is bifurcated, with the "defenders of the welfare state" describing in dramatic terms the sufferings of the destitute and disadvantaged while dismissing any mention of the requirements of harmonious economic growth. Those are just narrow-minded "fiscal" arguments that no compassionate person would consider. On the other side, one encounters economic arguments in which the need for a "social safety net" is relegated to an aside, and where the authors have failed to consider the social consequences of the rules they propose. Both sides usually refrain from supporting their positions with ethical considerations. It is high time for us to insist on a synthesis of outlook, in ourselves and others. Neither side has the right to espouse social criteria or economic arguments alone.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

A review of Principles 1 through 9 leaves open several important questions whose discussion would extend beyond the bounds of this study. Further analysis is required to decide the extent to which the various pairs and ensembles of postulates are reconcilable and the extent to which they have tradeoff relations. For instance, Principle 1 (individual freedom and responsibility) and Principle 5 (the responsibility of the state) are not irreconcilable, although clearly the further we take one, the less scope remains for the other. No prior theoretical consideration can preclude the need to make a specific, responsible choice in each case. As mentioned in the introduction, the principles presented here are intended to serve as mementos, or a checklist, so that none will be forgotten when programs, legislation, and regulations are drafted, evaluated, and enacted. Even when decision makers are obliged to make a concession on some principle, let them do so consciously, wrestling with their conscience and common sense before accepting the compromise. Those who truly espouse the principles proposed here will refrain from an extreme interpretation of any one of them if it conflicts with another.11

The choice of subject for this study may elicit the following counter-

argument. The scope for reform is given in all post-communist countries; it is constrained by economic and political conditions. The latter ultimately determine what kind of reform can be implemented. If reformers really want to fight for their ideas, they will have to make concessions. They may even have to manipulate public opinion. It is not always in their interests to declare clearly and unambiguously what principles they follow, what they intend, and what consequences can be expected.

The fate of reforms is generally known to be decided in the political arena. Among the tasks of academic research, I consider it important to examine the chances of welfare reform from the angle of political economy.12 I have tried to do this previously, taking a positive political-economy approach to the problem. However, I hope it will prove useful, as a complement to such positive research, to approach the issue from the opposite side as well. The question worth asking is not just how we can and must take the next steps, starting from where we now stand; it is also vitally important to ask where we really want to go. Particularly in the case of the welfare sector, it is worth considering the desired terminal state, because the answer is highly debatable and indeterminate in historical terms, and because, as I say, there is no country to serve as a real model, a pattern we might wish to follow.

The nine principles expounded in this study are not tied to any particular party, in Hungary or elsewhere in the post-communist region. They cannot be pigeon-holed in the usual way. They are neither ''left-wing" nor "right-wing," or to use American terminology, they do not correspond with what the traditional "liberal" or "conservative" ideas would suggest. They are dissociated from the earlier strand of social democracy, which saw as its main task the fullest possible construction of a welfare state, and which bears part of the historical blame for the exorbitant lengths to which this concept was taken. They are also dissociated from the cold-hearted radicalism that would dismantle all the achievements of the welfare state, and the ideologues who are uncritically biased against the state and in favor of the market. The set of nine principles represents a specific "centrist" position, and though dissociated from the traditional left and right wings, draws noteworthy ideas and proposals from both. My motive in doing so is not to make both sides like what I say. That might well rebound, so that neither side would approve. I have drawn up these nine principles in the belief that they form an integral whole.

The perspective behind this study is akin to that of many other authors, in political and in academic life alike. Perhaps it is not too soon to claim that this constitutes an international trend, which has not yet found an appropriate

name for its view of the world. It has both feet firmly planted in capitalism. It does not seek a third road. However, it does seek, not just with empty wishes, but by building up appropriate institutions, to ensure that capitalism has something more than a human face: a human heart and mind as well. It seeks to build much more firmly on individual responsibility, the market, competition, private ownership, and the profit motive, and it rejects much more strongly the proliferation of bureaucracy and centralization than old-style social democracy used to do. On the other hand, it does not accept any of the Eastern European variants of ultraconservatism. It seeks to apply the principle of solidarity not simply through individual charitable action; within certain bounds, it is prepared to countenance state redistribution for this purpose. It has no illusions about the market, and it does not reject all state intervention out of hand.

The historical experiences of the future will decide what effect this emerging intellectual and political trend will have on the transformation of the welfare sector.

REFERENCES

Andorka, R., A. Kondratas, and I.G. Tóth 1994 Hungary's Welfare State in Transition: Structure, Initial Reforms and Recommendations. Policy Study No. 3 of The Joint Hungarian-International Blue Ribbon Commission. Indianapolis, IN: The Hudson Institute, and Budapest: Institute of Economics.

Atkinson, A.B., and J. Micklewright 1992 Economic Transformation in Eastern Europe and the Distribution of Income. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Berlin, I. 1969 Four Essays on Liberty. London: Oxford University Press.

Buchanan, J.M. 1986 Liberty, Market and the State: Political Economy in the 1980s. Brighton, England: Wheatsheaf Books.

Buchanan, J.M., and G. Tullock 1962 The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Csontos, L., J. Kornai, and I.G. Tóth 1996 Tax-awareness and the Reform of the Welfare System. Results of a Hungarian Survey. Discussion paper No. 1790, Harvard University.

Culpitt, I. 1992 Welfare and Citizenship: Beyond the Crisis of the Welfare State. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Davis, L.E., and D.C. North 1971 Institutional Change and American Economic Growth. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Goldstein, E., A.S. Preker, O. Adeyi, and G. Chellaraj 1996 Trends in Health Status, Services and Finance: The Transition in Central and Eastern Europe. Volume I. World Bank Technical Paper No. 341. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Klimentová, J. 1996 Possibilities of the Transformation of the Financing of Pension Insurance in the Czech Republic. Unpublished paper, Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, Prague.

Kornai, J. 1972 Rush versus Harmonic Growth. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

1992 The postsocialist transition and the state: Reflections in the light of Hungarian fiscal problems. American Economic Review 82(2):1-21.

1996 The Citizen and the State: Reform of the Welfare System. Discussion Paper Series, No. 32 (August). Collegium Budapest, Institute for Advanced Study, Budapest.

Lindbeck, A. 1996 Incentives in the Welfare-State, Lessons for Would-Be Welfare States. Seminar Paper, No. 604 (January). Institute for International Economic Studies, Stockholm University.

Lindbeck, A., and J.W. Weibull 1987 Strategic Interaction with Altruism: The Economics of Fait Accompli. Seminar Paper, No. 376. Institute for International Economic Studies, University of Stockholm.

Lindbeck, A., P. Molander, T. Persson, O. Petersson, A. Sandmo, B. Swedenborg, and N. Thygesen 1994 Turning Sweden Around. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Milanovic, B. 1997 Income, Inequality, and Poverty During the Transition. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

Nelson, J.M. 1992 Poverty, equity, and the politics of adjustment. Pp. 221-269 in The Politics of Economic Adjustment, S. Haggard and R.R. Kaufman, eds. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Niskanen, W.A. 1971 Bureaucracy and Representative Government. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

North, D.C. 1990 Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Nozick, R. 1974 Anarchy, State and Utopia. New York: Basic Books.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development 1995 Hungary. OECD Economic Surveys (September). Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Rawls, J. 1971 A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rose, R., and C. Haerpfer 1993 Adapting to Transformation in Eastern Europe: New Democracies Barometer II. Studies in Public Policy, No. 212, Centre for the Study of Public Policy, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.

Sen, A. 1973 On Economic Inequality. Oxford: Clarendon Press and New York: Norton.

1990 Acceptance speech at the award ceremony for the second Senator Giovanni Agnelli International Prize in 1990 (June 14, 1990). The New York Review of Books 37(10):49-54.

1992 Inequality Reexamined. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, and Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

1996 Social commitment and democracy: The demands of equity and financial conservatism. Pp. 9-38 in Living as Equals, Paul Barker, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sipos, S. 1994 Income transfers: Family support and poverty relief. Pp. 226-259 in Labor Markets and Social Policy in Central and Eastern Europe. The Transition and Beyond , Nicholas Barr, ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Tullock, G. 1965 The Politics of Bureaucracy. Washington, DC: Public Affairs Press.

United Nations Children's Fund 1994 Crisis in Mortality, Health and Nutrition. Central and Eastern Europe in Transition, Public Policy and Social Conditions. Economies in Transition Studies, Regional Monitoring Report, 1994 August. Florence, Italy: UNICEF, International Child Development Centre (ICDC).

World Bank 1994 Averting the Old Age Crisis. The World Bank Policy Research Report. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

1995a Hungary: Structural Reforms for Sustainable Growth. First draft. Document of the World Bank, Country Operations Division, Central Europe Department, Report No. 3577-HU, February 10, Washington, DC.

1995b Hungary: Structural Reforms for Sustainable Growth. Document of the World Bank, Country Operations Division, Central Europe Department, Report No. 13577-HU, June 12, Washington, DC.