6

Immigrants and Natives in General Equilibrium Trade Models

Daniel Trefler

Nothing captures the links between trade and migration better than the discussions about whether migration belonged on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) bargaining table. On the one hand, the free flow of goods was viewed by the U.S. Commission for the Study of International Migration and Cooperative Economic Development (1990) as the single most important remedy for stemming illegal immigration. On the other hand, as was the case for U.S. citrus producers threatened by NAFTA, expanded quotas for seasonal migrants were advanced as an alternative to the free flow of goods. Stated crudely but accurately, NAFTA was often seen in terms of a trade-off between expanded imports of Mexican goods and expanded "imports" of Mexican people, legal and illegal.

Interest in trade and migration stems from the enormous disparity between U.S. and Mexican wages. For example, Samsung recently moved its picture tube production facilities from New Jersey where it paid workers $9 an hour to Tijuana where it now pays workers $1.10 an hour (New York Times, May 23, 1996). It would seem that even the most misguided of U.S. managers should long ago have recommended a move south. If so, why are there any jobs left in the United States? The Mexicans play the flip side of this sad song. If wages are so high in the United States, why are there any Mexicans left in Mexico? The answer, of course, is the focus of the NRC Panel on the Demographic and Economic Impacts of Immigration.

There are tangible concerns about the impact of trade and immigration on a U.S. labor force that is reeling from three decades of rising wage inequality. As is well known, U.S. average wages have stagnated, and the spread in wages

between the highest- and lowest-paid workers has grown by 40 percent (Murphy and Welch, 1993). This has naturally led to a suspicion that competition from unskilled foreign workers is at the heart of the trend. The sense is that U.S. workers are getting the short end of the globalization stick and are victims of a U.S. immigration policy that is out of control.

This chapter is divided into two parts. The first two sections outline the incentives to migrate and the impact of immigration on native welfare and income distribution. I show how immigration changes the allocation of industry outputs and changes the terms of trade in ways that significantly alter Borja's (1995) conclusions about the costs and benefits of immigration. There are two major lacunae in this chapter. The first deals with income redistribution through the tax system. As I document in what follows, the impact of immigrants is felt unevenly by the native population. This means that the tax system can and should be used to redistribute income from native losers to native winners. How this is best done is discussed by Wildasin (1991, 1994). The second lacuna is that all the models presented here have predictions that hinge critically on the full employment assumption. However, models of immigration and trade with unemployment are developed extensively in Razin and Sadka (1996). Their survey also deals with the fiscal burden of immigrants. In the third section I offer new empirical results about trends in earnings convergence across 75 countries and hence about the supply of immigrants to the United States. In the final section I present a new factor content study whose results significantly differ from those of previous research and point to a large negative impact of changing trade flows on America's least skilled workers. I then offer some caveats about how the lack of a well-defined policy experiment underlying the existing trade-and-wages empirical work has often led to the misinterpretation of that work.

THE IMMIGRATION SURPLUS IN A TWO-GOODS ECONOMY

Borjas (1995) made the important point that we focus on those who lose from immigration despite the fact that there are also those who benefit. In a stylish exposition, Borjas then showed that even in simple situations it is possible that the benefits created by immigration outweigh the losses. This is the "immigration surplus." Before assessing how the global environment might influence this conclusion, I present Borjas's idea. His original exposition was in terms of a single good, but because international trade requires at least two goods (exports and imports) I need an extension of his results. I do this using the specific factors model of international trade (Mayer, 1974; Mussa, 1974).

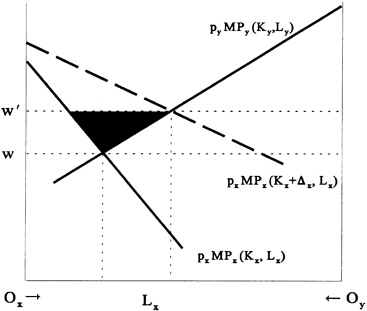

Let x and y be two industries. Each has a stock of an industry-specific factor (Kx and Ky) that has no value except when employed in its own industry. It may be capital, the industry-specific portion of a worker's human capital, union rents, etc. The other factor is labor. Labor is mobile between industries and earns wage w in both industries. The economy-wide labor supply is L of which Lx is em-

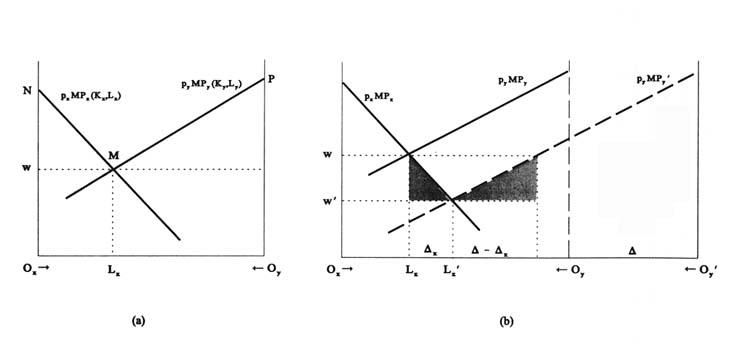

ployed in industry x and Ly in industry y. Let MPx (Kx, Lx) be the marginal product of labor in industry x. Labor demand in industry x is calculated from the value of the marginal product of labor, px MPx (Kx, Lx). Panel (a) of Figure 6-1 illustrates labor demand functions for industries x and y. Industry x (y) demand is read from the left (right) origin and the length of the figure's base is the supply of labor in the economy. At wage w, labor supply (L) equals the sum of the industry labor demands (Lx + Ly). The income generated by industry x is the area bounded by OxLxMN of which OxLxMw goes to labor and wMN goes to the specific factor. Industry y's income of OyLxMP is similarly divided between labor and the specific factor.

The impact of migration on native welfare depends on whether a specific factor or labor is migrating. The case of migrating labor is shown in panel (b) of Figure 6-1 as an increase in the base of the graph. Δ immigrants arrive. Industry y labor demand shifts right by Δ from py MPy to py MPy´ so that it is unchanged relative to its new origin Oy´. Δx immigrants find employment in industry x and Δ — Δx find employment in industry y. Competition between native labor and immigrants drives down the wage to w´, thus transferring income (w — w')L from native labor to the specific factors. Native labor loses at the expense of capital. Against this is an efficiency gain. Because immigrants complement the specific factors, immigration increases the specific factors' incomes. Net of the transfer from labor, the increases are given by the two shaded areas in Figure 6-1(b), one for industry x and one for industry y. These triangles are Borjas's "immigration surplus" generalized to two industries. Immigration of an industry-specific factor also creates an immigration surplus. In fact, that analysis is very similar to Borjas's analysis of immigrant externalities.1Immigration in this setting thus appears unambiguously beneficial .

GENERAL EQUILIBRIUM MODELS OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Many of the gains from immigration can be expected over the very long periods it takes for immigrants to assimilate. One would therefore need to know whether the immigration surplus exists in long-run models. Unfortunately, the specific factors model deals with the short run. It allows industry-specific factors to earn rents that are neither equalized across industries nor dissipated over time. Restated, the model does not impose the long-run equilibrium condition of zero profits. In this section I present three long-run general equilibrium models of international trade: the Heckscher-Ohlin model with its factor price equalization theorem, the Ricardian model, and a model of increasing returns to scale.

|

1 |

The relevant diagram for immigration of Kx appears as Appendix Figure 6-A1. When immigrants are mobile factors and convey a positive externality, the analysis is just a mix of Figures 6-1(b) and 6-A1. The immigrants convey a surplus by complementing existing capital [Figure 6-1(b)]. In addition, the externality raises native labor productivity and so leads to the Figure 6-A1 analysis, but with both shaded areas contributing to the immigration surplus. |

Factor Price Equalization

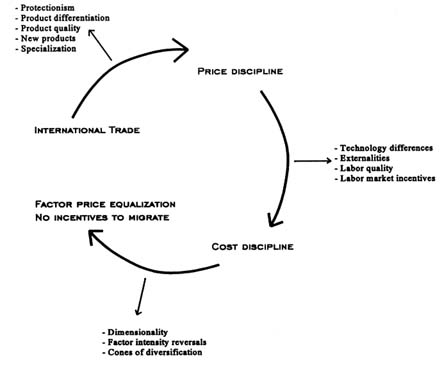

As the short-run specificity of Kx and Ky dissolve so that capital is mobile between industries, one ends up with the long-run Heckscher-Ohlin model. In this model international trade is a source of product market competition that drives profits to zero. Zero profits in turn impose wage discipline on producers. The model makes a set of strong assumptions aimed at isolating the wage-disciplining effects of trade from all other factors. Consider a perfectly competitive world with constant returns to scale in which countries are identical in every respect except in their endowment of the two factors. In this section I call them skilled labor (S) and unskilled labor (U). Let wS and wU be wages for these two types. There are two goods (x and y) with prices px and py and constant returns to scale production functions fx(S,U) and fy(S,U). Figure 6-2(a) plots the unit-value isocost line giving pairs of skilled and unskilled labor costing one dollar. The figure also plots unit-value isoquants, that is, pairs of skilled and unskilled labor yielding one dollar of output. If product price px is high it takes very little labor to produce a dollar of output [see Figure 6-2(a)]. This leads to positive profits and industry expansion that drive down the price; conversely for low prices. The zero-profit equilibrium is illustrated by the tangency of the two curves in Figure 6-2(a). General equilibrium is illustrated in Figure 6-2(b), where industries x and y both have zero profits. As drawn, industry x is the capital-intensive industry. Because prices of goods and production functions are the same in all countries, the unit-value isoquants are the same in all countries. Because only one isocost can be tangent to both isoquants, unit-value isocosts are the same in all countries. Reading off the isocost intercepts, it follows that wS and wU are the same in every country. This is the factor price equalization theorem. It states that a worker earns the same in all countries. Factor price equalization therefore implies that there are no incentives to migrate.

Obviously, the prediction of this theorem is false. But this is the wrong criterion for evaluating it. Like all good theories, factor price equalization uses extreme assumptions to isolate just one of several determinants of international wage differences, namely, the tendency for trade with developing countries to place downward pressure on U.S. wages. The popular press terms this "leveling down." More flamboyantly, Ross Perot calls it the "giant sucking sound." Figure 6-3 explains why the theory is so compelling in a way that abstracts from mathematical detail. International trade forces producers to charge a common price for their goods. With zero profits, this means that they must all have the same production costs. This cost discipline implies, under certain restrictions, that wages will be the same in all countries. Figure 6-3 also points out other determinants of international wage differences that disguise the tendency toward factor price equalization. I do not discuss these, as the main points are either familiar, obvious, or overly technical.

FIGURE 6-2

Factor price equalization theorem.

The Heckscher-Ohlin Model

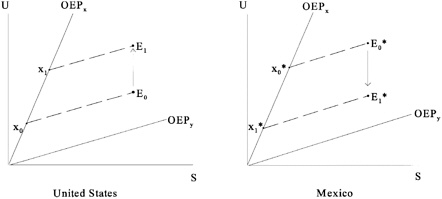

If workers' wages are the same across countries then there is no incentive for migration. In the jargon of international trade economists, trade is a substitute for migration (see Markusen, 1983). However, it remains possible that immigration is beneficial to natives. Figure 6-2(b) illustrates an output expansion path giving the combination of skilled and unskilled worker pairs that minimize costs at wages wS and wU. With constant returns to scale, an output expansion path is a ray through the origin whose slope depends only on the ratio of factor prices wS/wU. Figure 6-4 plots the x and y output expansion paths for the United States.

FIGURE 6-3

Factor price equalization.

Point E0 illustrates the U.S. endowment of skilled and unskilled labor. In a full employment equilibrium all these workers must be employed. This occurs only if industry x employs the combination of skilled and unskilled workers given by x0 and industry y employs the combination of workers given by E0-x0. Suppose the United States allows immigration of unskilled Mexican labor so that E0 moves to E1 and x0 moves to x1. Figure 6-4 illustrates what happens in Mexico. Assume initially that factor price equalization holds so that the Mexican and U.S. expansion paths are identical. Because Mexican emigrants are U.S. immigrants, E1 - E0 equals E0* - E1*. Assume momentarily that the migration leaves wages and hence expansion paths unaltered. Then x0 + x0* must equal x1 + x1*; likewise in the y industry.2 That is, total inputs into each industry are unaltered. Consequently, so are total outputs. Because earnings are the same, product markets clear at the old product prices. But if product prices do not change, then factor prices do not change [see proof of factor price equalization in Figure 6-2(b)]. Migration is consistent with unchanged product and factor prices. Thus,

|

2 |

For the y industry (E0 - x0) + (E0* - x0*) must equal (E1 - x1) + (E1* - x1*). |

FIGURE 6-4

Migration in a Heckscher-Ohlin model.

in this model, immigration has zero welfare implications for both natives and immigrants. The immigration surplus is zero.

Modified Factor Price Equalization and the Heckscher-Ohlin Model

The previous model can be modified to allow for international differences in factor quality and technology. Let πc be a measure of productivity in country c and let πcfg (S,U) be country c's production function for good g (g = x, y). Unlike the Heckscher-Ohlin model, there are international technology differences as indicated by the πc.3 With constant returns to scale, πcfg (S,U) = fg (πcS, πc U). Thus, another interpretation of the πc is that they capture international differences in input quality (e.g., better labor market incentives or higher school quality). Let Sc be the national endowment. Sc* EQUIV πcSc is the national endowment measured in internationally comparable or productivity-adjusted units. One unit of Sc* is equivalent to 1/πc units of Sc (i.e., Sc = Sc*/πc). Because one unit of Sc earns WSc, it follows that one unit of Sc* earns wSc/πc; likewise for Uc* EQUIV πc Uc and wUc/πc.

The amended model is exactly the same as the original Heckscher-Ohlin model but with (Sc*, Uc*) replacing (Sc, Uc) and (wSc/πc, wUc/πc) replacing (wSc, wUc).4 Thus, factor price equalization holds for productivity-adjusted wages:

wSc/πc = wS,US/πUS for all c. (1)

|

3 |

In Trefler (1993b, 1995) I considered the more general model fg (πSc S, πUc U). This allows for Hicks non-neutral factor-augmenting international technology differences. |

|

4 |

For example, Figure 6-2 has unit-value isoquants px fx (S*,U*) = 1 and unit-value isocost line (wSc/πc)S* + (wUc/πc)U* = 1. It follows that (wSc/πc) and (wUc/πc) are equalized across countries. |

To understand this, if country c labor were half as productive as U.S. labor (πc/ πUS = 1/2), then one would expect country c wages to be half the U.S. wage (wSc = wS,US πc/πUS). Also, the Heckscher-Ohlin prediction about location of production and patterns of trade holds, but again with (Sc,Uc) replaced by (Sc*,Uc*).

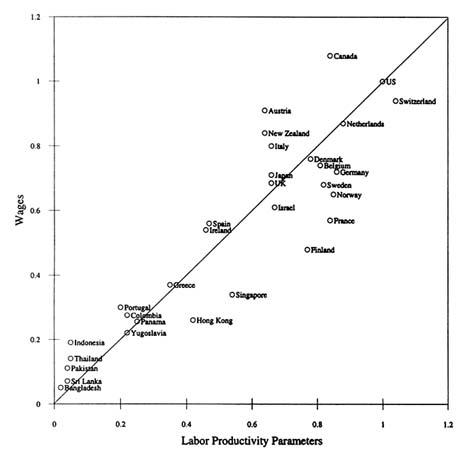

This amendment is important empirically. Factor price equalization and the Heckscher-Ohlin predictions do not work well empirically (Trefler, 1995). On the other hand, the above modification does work well. Specifically, in Trefler (1993b) I calculated the unique π c/πUS that make the Heckscher-Ohlin prediction work perfectly for aggregate labor. I then showed that equation (1) holds almost exactly when the calculated πc/πUS are plugged in. Figure 6-5 plots relative wages wc/wUS against πc/πUS. Modified factor price equalization [equation (1)]

FIGURE 6-5

Modified factor price equalization.

implies that all the data should lie along the 45° line as is in fact the case. This kills two birds with one stone: both the factor price equalization and the Heckscher-Ohlin model work well empirically after a slight amendment that accounts for international technology or input quality differences.

Such a model may lead to predictions about the impact of immigration that are very different from those of the textbook Heckscher-Ohlin model. Consider a skilled worker deciding whether or not to migrate from his or her low-productivity country to the United States. If πc is an attribute of the worker (e.g., a poor education) then a migrant will have low productivity no matter which country he or she works in and so will not earn more in the United States. There will be no incentive to migrate and no labor market impacts of migration. On the other hand, if productivity is an attribute of the country (e.g., poor labor market incentives) then the worker will earn more in the United States and so will have an incentive to migrate. Suppose skilled workers migrate to the United States and become more productive. This is equivalent to increasing the world supply of skilled workers relative to that of unskilled workers. This expands world production of good x relative to good y (the Rybzcynski effect). As a result, px /py falls. This reduces real wages of skilled natives and raises real wages of unskilled natives (the Stolper-Samuelson theorem). Once again, general equilibrium models of migration yield impact channels very different from those outlined by Borjas (1995). In this case, migration changes migrants' productivity and thus affects the terms of trade.

The Ricardian Model

To focus more clearly on the terms-of-trade effect, consider a long-run, zero-profit economy in which labor is the only productive input. Let g index goods. One unit of output is produced using ag units of labor. Restated, 1/ag is both labor productivity as well as the marginal product of labor. I use an asterisk to denote foreign country values (e.g., ag*). Following Dornbusch et al. (1977), I order the goods index g so that

a1/a1* < … < ag´/ ag´* < … < aG/ aG*. (2)

For some g´, the home country is said to have a comparative advantage in goods g ≤; g´. This implies that the home country exports goods g ≥; g´ and imports goods g > g´. Let w and w* be wages in the two countries.

For long-run zero profits the price of good g (pg) must equal the cost of producing one unit of good g (wag or w* ag*). I write w/pg > 1/ag to denote zero profits and w/pg > 1/ag to denote losses. For almost all parameter values each good will be produced in only one country. This production specialization result is very different from what was assumed in the Heckscher-Ohlin model and frees the model from the factor-price-equalization straightjacket. If w/pg = 1/ag then the home country produces good g, not the foreign country. If w/pg > 1/ag then the

foreign country produces good g, not the home country. For simplicity, assume that there are three goods and that initially the home country produces only good 1.

Consider the effect of immigration.5 The immigrants are employed producing good 1, thus creating excess supply of the good at prevailing prices. The resulting home trade deficit drives down the home wage until w/p2 = 1/a2. At that point the home country produces good 2. Likewise, in the foreign country w* rises until industry 2 shuts down. What has happened to real wages and per capita native utility? It is simple enough to show that there is a fall in w/p2 and w/p3 and no change in w/p1.6 Thus, w has fallen relative to any basket of consumer prices. The first conclusion is that migration lowers per capita native welfare. That is, Borjas's immigration ''surplus" is negative. To be crystal clear, the negative immigration "surplus" is driven by the fact that immigration adversely affects the home country's terms of trade. Because immigrant and native labor compete for the same jobs at the same wages, the home country can only absorb the immigrants in low-productivity industries that spring up in response to immigration. One should think of these industries as garments or citrus fruit industries that would disappear in the absence of migrant workers. There are no downward-sloping labor demand functions as in Borjas's analysis, only general equilibrium industrial reallocations between countries in response to changes in the terms of trade.7

External Increasing Returns to Scale

Increasing returns to scale potentially generate an immigration surplus. One sees this in the opening up of prairie agriculture: without mass immigration there would not have been large enough grain production to warrant investment in transportation infrastructure. In this subsection I examine the immigration surplus in a long-run increasing returns to scale model. In particular, I consider Helpman's (1984) general equilibrium model in which perfect competition is preserved by assuming that returns to scale are external to the firm.

|

5 |

The analysis that follows is informal. A strict statement of results, and one that holds for a continuum of goods rather than three goods, can be found in Dornbusch et al. (1977). The importance of Cobb-Douglas preferences is clearly explained in that paper. I therefore do not deal with the issue here. |

|

6 |

The proof is as follows. Because home always produces good 1, w/p 1 = 1/a1 is unchanged by migration. w/p2 has fallen to 1/a2. Because w* has risen and w*/p3 = 1/a*3 is unchanged, p3 has risen. Hence, w/p3 has fallen. |

|

7 |

There is a second conclusion, this one regarding the incentives to migrate and hence the pool of potential migrants. Assume that migration is from poor to rich countries (w > w*). Migration causes w and per capita native utility to fall. Symmetrically, it causes w* and per capita foreign utility to rise. Hence, migration unambiguously leads to international convergence of wages and per capita utility. This is particularly surprising in view of the fact that increased trade flows need not lead to increased convergence of wages or utility (Dixit and Norman, 1980). |

Labor is the only factor and national labor supply is denoted L in the United States and L* in the foreign country. There are two goods, x and y. One unit of y is produced with one unit of labor. Let Lj be the amount of labor employed by firm j, let xj be firms j's output, and let x = Σjxj be industry output. Firm j's production function is xj = x1/2Lj. The term x1/2 captures increasing returns to scale. Scale returns are external to the firm in the sense that each firm treats x1/2 as if it were exogenous. Demand is given by a representative consumer with Cobb-Douglas preferences.

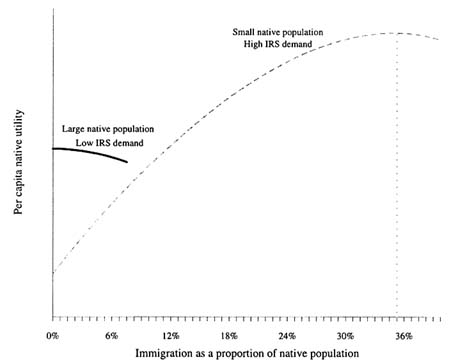

There are many equilibria in this model including ones that display factor price equalization and the Heckscher-Ohlin result that immigration has no impact on native welfare (see Appendix Table 6-A1 for a description of such an equilibrium). An equilibrium with a Ricardian terms-of-trade flavor is one in which the United States produces only x and the foreign country produces only y. Immigration has two impacts. First, immigration increases native productivity. To see this sum, xj = x1/2 Lj across firms, I use ΣjLj = L to obtain x = x1/2 L, or x = L2, or finally x/L = L. That is, U.S. productivity x/L rises with the size of the labor force L. It follows that immigration improves native productivity and hence welfare by increasing the labor force. Second, immigration expands output of x. This leads to a fall in the price of x because output expansion leads to lower units costs that zero-profit firms pass on to consumers and because consumers need lower prices as an inducement to purchase more. The fall in the price of x is a negative terms-of-trade shift that reduces native welfare. It follows that there is a trade-off between the terms-of-trade effect and the productivity effect. A diminishing marginal rate of substitution in consumption implies that the negative terms-of-trade effect grows faster than the positive productivity effect. This leads to an optimal level of immigration (possibly zero) beyond which new immigrants reduce native welfare. This is illustrated in Figure 6-6, which plots per capita native utility against the ratio of immigrants to natives. The dashed curve involves a scenario with high demand for x relative to population size. Immigration improves native welfare at low levels of immigration, but worsens it beyond the socially optimal level of 35 immigrants per 100 natives. The solid curve involves a scenario with low demand for x relative to population size.8 With a large native work force, the socially optimal level of immigration is zero. The conclusion to be drawn is that immigration policy should target immigrants who, perhaps because of rare skills, are likely to establish new industries that interact synergistically with existing ones. Being a new industry, the terms-of-trade effect will be negligible. A good example is Russian emigrés to Israel who set up the Israeli software industry.

|

8 |

See Appendix Table 6-A1 for an algebraic expression for per capita native utility. In both scenarios, L + L* = 1. In the dashed curve scenario, L = 0.4 and the Cobb-Douglas consumption share for x is 0.8. In the solid curve scenario, L = 0.67 and the consumption share for x is 0.75. The solid line terminates early on because beyond a certain level of immigration the foreign country does not have enough workers to meet world demand for y, and the specialization equilibrium disappears. |

FIGURE 6-6

Effect of immigration with increasing returns to scale (IRS).

Demand-Side Models

Much of the analysis of this section has used the assumption that immigrants and natives consume the same bundle of goods. This assumption of consumption similarity is central to general equilibrium trade models for a simple reason. A country's industrial output is either consumed domestically or exported. Most trade theories begin by predicting a country's structure of industrial output. Predictions about industrial structure are then translated into predictions about trade flows by assuming that countries have similar consumption. This point is the main focus of Trefler (1996). There is, however, empirical evidence that immigrants affect trade patterns in ways that violate the assumption of consumption similarity. For example, immigrants' consumption patterns differ from those of natives so that immigrants demand more foreign goods. Also, immigrants import more from their countries of origin because of immigrant social networks (see Baker and Benjamin, 1996).

Conclusions

We tend to focus on those who lose from immigration and ignore those who gain. Borjas (1995) showed that in simple situations the gainers outweigh the losers and there is an immigration surplus. Although the insight holds in at least one short-run general equilibrium model of international trade (the specific factors model), it need not hold in long-run, zero-profit models. In models displaying factor price equalization, zero profits pin down wages so that immigration has no effects. This radically differs from Borjas's (1995) conclusion. The intense product market competition and ensuing wage discipline associated with factor price equalization are most common in lowand mid-level manufactures. One should therefore not expect much from an immigration policy that merely provides excess labor supply for these industries. In the Ricardian model, immigration adversely affects the home country's terms of trade, which unambiguously reduces native welfare while at the same time "ghettoizing" immigrants in low-productivity industries such as garments and citrus picking. These industries would otherwise disappear in the absence of immigrant labor. I doubt that the terms-of-trade effects are large enough to seriously reduce native welfare. Evidence from studies of trade liberalization indicates that the U.S. terms of trade are driven by the dynamics of new product introduction, not immigration. I find ghettoization to be a more significant problem. Finally, with increasing returns to scale the adverse Ricardian terms-of-trade effect is partially mitigated by an immigrant externality. Provided that immigrants bring skills that enhance the productivity of natives, immigration can improve native welfare.

CHANGING INCENTIVES FOR MIGRATION: EVIDENCE ON FACTOR PRICE CONVERGENCE

Given the central role of factor price equalization in determining whether there is an immigration surplus, it is worth reviewing the extent to which wages differ across countries and whether there is any tendency for wages or skill prices to converge over time. We do not know exactly how unequal the wages are because we do not have comprehensive data on international wage differences purged of human capital and other effects. However, international wage differences seem too large to be accounted for solely by such effects. For example, Filipino migrant bricklayers earn three times more in Singapore than in Manila and eight times more in Japan (see Appendix Table 6-A2 for details). By implication, there are large incentives to migrate and select the best host country.

Evidence on cross-country wage convergence can be garnered from the UNIDO INDSTAT database. The data are based on manufacturing surveys of payroll and employment to which UNIDO introduced a degree of international comparability. I cleaned this data set, applied purchasing power party corrections, and subjected it to internal and external validation. The data consist of 75

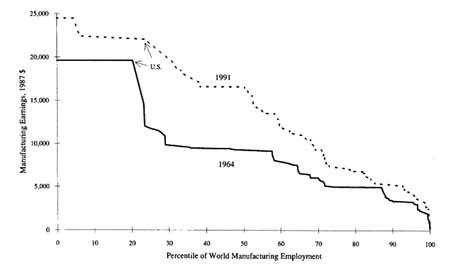

FIGURE 6-7

Lorenz curve (Leamer's waterfalls).

countries over the period 1963–1992. They are informative about broad differences in the earnings of widely divergent economies. Details for any individual country should be treated with caution. Full data documentation will appear in a separate paper. The data have been smoothed by a three-year moving average. In what follows, years refer to the midpoint of the three-year average.

Figure 6-7 reports a variant of a Lorenz curve or Leamer (1992) "waterfall" for the years 1964 and 1991. Each "kink" in the curve represents a data point for one of the 75 countries. For example, in 1964 U.S. average manufacturing earnings were $19,600, and the United States accounted for 25 percent of world manufacturing employment. In contrast, Japanese earnings averaged $5,000, and Japan accounted for 13 percent of world manufacturing employment. The 1964 data document substantial international earnings differences. Leamer encourages us to see the 1964 curve as a waterfall seeking a flat level, that is, seeking earnings equalization in manufacturing. The impression is that equalization would require U.S. wages to fall sharply but developing country earnings to rise only slightly. The 1991 curve shows no such pattern. If so, then pressures for migration to the United States remain similar to what they were 30 years ago. Unfortunately, this evidence regarding failure of earnings convergence is not persuasive. Convergence may have been disguised by opposing movements in unobservables such as capital accumulation, human capital accumulation, other sources of worker heterogeneity, anomalies in global integration, and transition dynamics. In the next two subsections I attempt to control for some, though not all, of these potentially offsetting factors.

Worker Sorting

Industry of affiliation conveys two pieces of information about the sources of earnings dispersion. First, workers sort across industries based on unobservable characteristics such as education. Second, certain industry characteristics such as capital intensity are likely to be common across countries. Thus, industry of affiliation offers an ad hoc control for unobserved worker and industry characteristics. To exploit this I consider a within-industry variance decomposition of earnings. Let g index industries, c index countries, and t index time. Let egct be employment and let wgct be log earnings where the italics denote logs. Let ect = Σ g egct, egt = Σ c egct, et = Σ c,g egct, wct = Σ gwgct egct/ect, wgt = Σ cwgct egct/egt, and wt = Σ c,gwgct egct/et. The variance of log earnings between countries is

σt2 = Σc (wct - wt)2 ect/et. (3)

Within-industry variance is defined as

σ2wt = Σg {Σc (wgct - wgt)2 egct/et}. (4)

The term in braces is like σt2 except that in equation (4) one centers around a single industry rather than around the average across industries. σt2 and σ2Wt are reported in Table 6-1. In 1964 the standard error of log earnings across the 75 countries was 62 log points. This is comparable in size with the 70-30 log wage differential in the United States (Murphy and Welch, 1993). More important, there is no tendency toward earnings equalization for either between-country or within-industry standard errors.

In searching for convergence, the Heckscher-Ohlin model predicts that trade liberalization and factor accumulation will lead to changing industrial composition. This implies that variation in the employment weights of equations (3) and

TABLE 6-1 Standard Error of Log Earnings

|

1964 |

1991 |

1991-1964 |

|

|

TIME-VARYING EMPLOYMENT WEIGHTS |

|||

|

Between-country(σt) |

0.62 |

0.65 |

0.03 |

|

Within-industry (σWt) |

0.60 |

0.60 |

-0.01 |

|

Within-HK-K (σωt) |

0.35 |

0.37 |

0.02 |

|

FIXED (1991) EMPLOYMENT WEIGHTS |

|||

|

Between-country (σFt) |

0.74 |

0.65 |

-0.09 |

|

Within-industry (σWFt) |

0.76 |

0.60 |

-0.16 |

|

Within-HK-K σωFt) |

0.40 |

0.37 |

-0.03 |

|

NOTES: σt and σWt are defined in equations (3) and (4), respectively. σωt uses equation (3), but replaces wct with human and physical capital adjusted earnings i.e., with the estimated country fixed effects from equation (6). For σωt and σωFt, 1964 refers to the period 1963–72 and 1991 refers to the period 1983–92. |

|||

(4) is economically meaningful. To control for this I consider an Oaxaca or fixed-weight decomposition based on σ2W91- σ2Wt and report only the fixed-weight variance:

σ2WFt = Σg {Σc (wgct - wgt)2 egc1991/e1991}. (5)

σWFt is reported in Table 6-1. The striking feature is that during 1964–1991 the standard error of log earnings fell from 0.75 to 0.60 or 16 log points. Why fixing weights is so important is a question that Joe Hotz and I are actively pursuing. At any rate, this is the only evidence I have presented so far of earnings convergence.

Human and Physical Capital Formation

In the absence of labor force surveys of worker characteristics and manufacturing surveys of capital and other nonlabor inputs, it is impossible to adequately purge the earnings data of the human and physical capital effects that contribute to international earnings differences. As a second-best alternative, I control for human and physical capital by regressing the UNIDO manufacturing earnings data on the economy-wide stocks of education (Barro and Lee, 1993) and capital (Summers and Heston, 1991). In country c in year t let E ict be the population 25 years and older with education level i. There are four schooling categories: no education, primary education (usually grades 1–6), secondary education (usually grades 7–12), and some tertiary or college education (usually years 13+). Let Kct and Lct be the capital stock and population aged at least 25, respectively. I consider the regression

wct = Σiβi (Eict /Lct) + ΣiβKi (Eict /Lct)(Kct /Lct) + βK (Kct /Lct) + ωc + εct (6)

where wct is log wages and ωc is a country fixed effect to be estimated. ωc captures a variety of errors in the specification of equation (6). However, I heroically interpret it as the country average log wage after netting out international differences in human and physical capital. Thus, I refer to ω'c as the adjusted log wage. Our method here is similar to the way in which labor economists construct indicators for local labor markets (see Card and Krueger, 1992). In these studies the authors usually include quadratic and even cubic terms of the education variables. We have not tried this. Table 6-1 reports the variance decomposition for ωc when estimated separately for the periods 1963–1972 and 1983–1992. By construction, the estimated ωc must have a smaller standard error than the wct (after averaging across years). In fact, the standard error is almost half, suggesting that human and physical capital explain about half of the observed earnings dispersion. More important though, there is no strong evidence of convergence over time even when using fixed 1991 employment weights.

Conclusions

Given the rapid pace of globalization I am surprised that evidence of manufacturing earnings convergence is so difficult to find. It thus appears that supply pressures for migration to the United States remain strong and show little or no tendency to diminish over time.

TRADE, IMMIGRATION, AND WAGES

The debate about the extent to which trade and immigration have led to rising wage inequality in the United States has been one of the most fruitful empirical debates in international trade. In this section I briefly review the debate, present some new evidence, itemize differences in the way trade and immigration are expected to impact on native wages, and offer some methodological observations about constructing an econometric experiment that captures the impact of proposed trade and immigration policies.

Sources of Rising Wage Inequality

There are four contenders for the privileged position of having "immiserized" unskilled U.S. labor. The first is immigration. Borjas (1987) showed that immigrant cohorts have been increasingly unskilled. In addition, immigration levels tripled between 1988 and 1991. The second is international trade. There is a coincidence of globalization, the U.S. trade deficit, and rising U.S. wage inequality (e.g., Borjas and Ramey, 1993). The third is technology-induced skill upgrading, which has raised the demand for skilled workers relative to unskilled workers (e.g., Berman et al., 1994; Krueger, 1993; and Katz and Murphy, 1992). The fourth is capital deepening associated with a falling price of physical capital. To the extent that capital complements skilled labor and substitutes for unskilled labor (Goldin and Katz, 1996), capital deepening displaces unskilled labor and increases demand for skilled labor. The mainstream view among economists of the sources of rising wage inequality is that skill upgrading was far more important than immigration, which in turn was somewhat more important than international trade. The capital deepening hypothesis has not yet been investigated adequately.

Trade and Wages

Among the many arguments that have been advanced about the role of international trade, let me single out a few that support the mainstream view that trade is unimportant. (1) The timing is wrong for trade arguments. Juhn et al. (1993) used a variance decomposition to show that the rise in inequality is largely due to factors other than education and experience and that this residual compo-

nent of inequality began rising long before the major trade events of the late 1970s. (2) Trade is too small a component of the U.S. economy to explain major changes in the domestic economy. Krugman and Lawrence (1994) pointed out that the sector of the U.S. economy directly exposed to trade employs only about 20 percent of the work force. They argued that this 20 percent tail cannot wag the dog. Although persuasive, this argument suffers from a lack of theoretical support. It is easy to construct theoretical models in which the tail does wag the dog. For example, the Stolper-Samuelson impact of changing import prices on wage inequality can be made arbitrarily large simply by making the ratio of skilled to unskilled labor arbitrarily similar across industries. Even when countries do not produce the same range of goods so that the Stolper-Samuelson theorem no longer holds, wages are determined at the margin, and what may matter is how substitutable the marginal U.S. worker is with foreign workers (Leamer, 1996). (3) Rising wage inequality and skill upgrading have occurred within industries, not between industries (Davis and Haltiwanger, 1991). In the Heckscher-Ohlin model a fall in the price of the unskilled-intensive good drives down the unskilled wage. This leads firms to (a) hire unskilled workers and fire skilled workers and (b) expand output of skill-intensive industries to fully employ laid-off skilled workers. Both predictions are wrong empirically.9 An implication of this argument is that Stolper-Samuelson effects must have been small. Indeed, a number of studies have shown that product price movements have not been strong enough to entail large Stolper-Samuelson effects (e.g., Sachs and Shatz, 1994), though in view of data problems this empirical result may be misleading. To summarize, there are a number of persuasive arguments, none of them knockouts, that trade has not contributed significantly to rising wage inequality.

It is perhaps worth noting that changes in protection and exchange rates cannot readily explain average wage changes. Gaston and Trefler (1994, 1995) argued that U.S. levels of protection have been too small to explain average wage developments. This is true in spite of Trefler's (1993a) finding that the import-reducing effects of protection are much greater than previously thought. Revenga (1992) finds some evidence that the run-up of the dollar in the first half of the 1980s depressed U.S. wages.

Trade and Wages: A New Factor Content Study

The view that the tail cannot wag the dog has been confirmed in a number of factor content studies (e.g., Borjas et al., 1992). In this subsection I explain what a factor content study is and offer a challenge to existing studies. Let g index

|

9 |

Again, this is not entirely persuasive. Feenstra and Hanson (1996) considered the following model. Every industry includes both unskilled processes (assembly) and skilled processes (design). Offshore sourcing sends the low-skill processes abroad. This raises the average skill level of processes that remain in the United States and exposes unskilled U.S. workers to greater foreign competition (i.e., offshore sourcing explains within-industry skill upgrading and rising wage inequality). |

industries, t index time, and i index the level of education. Let adgt (i) be the amount of type i labor needed to produce one unit of good g in year t. Following the convention among labor economists, adgt (i) is defined as the amount of type i labor employed in industry g divided by industry output. In input-output terminology this is the "direct" input coefficient, hence the d superscript. The factor content of trade is the derived demand for labor induced by observed trade flows. Let Lt(i) be employment of type i labor in year t and let Mgt and Tgt be imports and net imports, respectively. Then expressed as a proportion of employment, the factor content of imports and net imports is calculated as

FMdt (i) = Σg adgt (i) Mgt/Lt(i) and FTdt(i) = Σgadgt (i) T gt/Lt(i). (7)

FTd92(i) - FTd72(i) is the change in demand for type i labor associated with the changing pattern of trade flows over the period 1972–1992. This interpretation is subject to a number of caveats that I will return to.

To calculate the factor content of trade, I use data for 103 trading partners accounting for well over 95 percent of U.S. trade. Trade data are from Statistic Canada's World Trade Data Base. The input coefficients are from the U.S. input-output benchmark tables, the U.S. Department of Commerce's Employment and Earnings series, and the Current Population Survey. In each case 1972 and 1992 data were used. Nominal data were double deflated as is required for input-output analysis.

Table 6-2 reports new calculations of the factor content of net imports and imports in 1992, and the change during 1972–1992. These appear in the four "direct" columns. The key column is that associated with "net imports, 1992–1972." For example, the all-labor factor content of net imports rose by 0.2 percentage points between 1972 and 1992, indicating that changing trade patterns have augmented the U.S. labor force by 0.2 percentage points. The numbers are uniformly small for all types of labor indicating that trade has had little impact. This would have been the conclusion of Borjas et al. (1992) had they continued their analysis to 1992 instead of ending in 1986, a year with a large trade deficit.

A problem with this factor content calculation is that it uses direct or partial equilibrium employment output ratios. This ignores Leontief's general equilibrium interactions in the economy. For example, producing steel requires inputs of transportation equipment which in turn requires more steel. Input-output analysis sums the direct and indirect effects to obtain "total" or general equilibrium effects. Let atgt(i) be this total labor demand induced by producing one unit of output for final demand. Factor content calculations based on atgt(i) are reported in the four "total" columns of Table 6-2. Using total requirements, the 1972–1992 change in trade patterns led to no change in the factor content of net imports (0.0%) despite a large increase in the factor content of imports (6.2%).

Wood (1994) initiated an interesting challenge to the factor content literature. He argued that both adgt(i) and atgt(i) are applied inappropriately. Although there are several elements to the argument, the one I find most intriguing is that a

TABLE 6-2 The Factor Content of Net Imports and Imports

|

NET IMPORTS |

||||||||

|

1992 – 1972 |

1992 |

|||||||

|

Education |

employment (1000s) |

direct % |

total % |

adjusted % |

employment (1000s) |

direct % |

total % |

adjusted % |

|

None |

-236 |

-6.3 |

-7.7 |

168.6 |

921 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

343.6 |

|

Primary |

-12,198 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

37.0 |

8,674 |

1.6 |

1.8 |

37.7 |

|

Secondary (entered) |

5,430 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

4.7 |

25,947 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

4.8 |

|

Secondary (complete) |

17,588 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

-5.6 |

45,005 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

-9.4 |

|

College |

22,909 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

-3.7 |

44,655 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

-5.6 |

|

All Labor |

33,492 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

125,201 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

|

IMPORTS |

||||||||

|

1992 – 1972 |

1992 |

|||||||

|

Education |

employment (1000s) |

direct % |

total % |

adjusted % |

employment (1000s) |

direct % |

total % |

adjusted % |

|

None |

-236 |

-5.8 |

-5.6 |

170.8 |

921 |

6.2 |

12.3 |

354.3 |

|

primary |

-12,198 |

4.9 |

9.1 |

45.7 |

8,674 |

8.2 |

15.7 |

51.6 |

|

Secondary (entered) |

5,430 |

3.1 |

6.8 |

10.9 |

25,947 |

5.7 |

12.4 |

16.0 |

|

Secondary (complete) |

17,588 |

3.6 |

7.6 |

1.7 |

45,005 |

5.9 |

12.9 |

2.7 |

|

College |

22,909 |

2.4 |

5.7 |

2.1 |

44,655 |

4.0 |

9.4 |

3.6 |

|

All Labor |

33,492 |

2.8 |

6.2 |

6.2 |

125,201 |

5.0 |

11.2 |

11.2 |

|

NOTES: See equation (7). |

||||||||

job performed by a high school dropout in the United States is probably performed by a primary school dropout in India. Feenstra and Hanson (1996) offered a complementary argument. Every industry includes both unskilled processes such as assembly and skilled processes such as design. Offshore sourcing sends the low-skill processes abroad so that imports are produced with much less skilled labor than are exports. For trade with developing countries, the factor content of trade is thus biased up for skilled labor and biased down for unskilled labor.

To implement this line of reasoning consider panel A of Table 6-3. I made up the numbers so as to simplify the presentation. In India, 25 percent of the population aged 25 or more has no education. In the United States, 25 percent of the population aged 25 or more has a secondary (entered) education or less (25% = 0% + 10% + 15%). I assume that what matters is one's position in the education distribution, not one's absolute level of education. For example, a job done by a U.S. worker with a secondary (entered) education or less is done by an Indian worker with no education. Panel A in Table 6-3 also gives a hypothetical example for the textiles industry. Suppose that production of one dollar of textiles in the United States requires 0.12 (= 0.00 + 0.02 + 0.10) workers with a secondary (entered) education or less. I assume that production of one dollar of textiles in India requires 0.12 workers with no education. Likewise, college U.S. jobs are assumed to be secondary (entered) Indian jobs. In practice, these adjustments were done for groups of countries and appear in Panel B in Table 6-3. For example, a job done by a U.S. worker with a secondary (completed) education is done in a high-income country by a worker with a secondary (entered) education and done in a middle-income country by a worker with a primary education. It is surprising how the education distribution of the U.S. is so ''right-shifted" compared with other countries —U.S. education levels are high. This leads me to the conclusion that the adjustments may be exaggerated. To investigate further, consider in Panel B in Table 6-3 the "Import Shares" columns. Sixty-five percent of U.S. imports come from high-income countries and face almost no adjustment. Moreover, this number has changed only a little since 1972. Low-income countries have only a small share of imports, and oil exporters produce very capital-intensive goods so that the adjustments can only have a limited effect. If the adjustments are to matter, it is for middle-income countries. But even here the change in import share is only 10 percent which in turn is only a small fraction of U.S. gross domestic product. Thus, it is by no means obvious that the adjustment will matter.

There is a basic asymmetry between imports and exports. Consider industry g. We observe atgt(i), the amount of type i labor used in observed U.S. production. Imports use less of educated labor and more of uneducated labor than is given by atgt(i). This is because the United States imports unskilled processes. I therefore use the adjustment in Panel B in Table 6-3 to calculate the type i factor content of imports from country c. On the other hand, exports probably use

TABLE 6-3 Method for Adjusting Labor Input Requirements

|

A. Hypothetical Example |

||||||

|

Secondary |

||||||

|

None |

Primary |

Entered |

Complete |

College |

||

|

Educational Attainment in Population 25+ |

||||||

|

United Statesa |

0% |

10% |

15% |

35% |

40% |

|

|

Indiaa |

25% |

35% |

40% |

0% |

0% |

|

|

Educational Attainment in Textiles (atgt(i)) |

||||||

|

United Statesb |

.00 |

.02 |

.10 |

.05 |

.03 |

|

|

Indiab |

.12 |

.05 |

.03 |

.00 |

||

|

B. Actual Adjustments |

||||||||

|

Secondary |

College |

|||||||

|

Import Shares |

None |

Primary |

Entered |

Complete |

Entered |

Completed |

||

|

Countryc |

1992 |

1972 |

(N) |

(P) |

(SE) |

(SC) |

(CE) |

(CC) |

|

Above Example |

N |

N |

N |

P |

SE |

SE |

||

|

High Income |

65% |

72% |

N |

N |

P |

SE |

SC |

CE |

|

Middle Income |

16% |

6% |

N |

N |

N |

P |

P |

SE |

|

Low Income |

10% |

13% |

N |

N |

N |

N |

P |

P |

|

Oil and CME |

9% |

9% |

N |

N |

N |

P |

P |

P |

|

a) Data are percent so that each row sums to 100%. b) Data are in numbers of workers per dollar of textile output. c) The World Bank country classifications are followed closely, but not exactly. |

||||||||

somewhat more of educated labor and somewhat less of uneducated labor than is given by atgt(i), because exports consist of skilled processes. To weaken my argument I nevertheless use atgt(i) to calculate the type i factor content of exports. By construction, the modification makes no difference to "all labor."

Factor contents calculated in this way are reported in the four Table 6-2 "adjusted" columns. It is remarkable that the no-education labor content of U.S. net imports grew an enormous 168.6 percentage points . It was 343.6 percent of the no-education labor force in 1992, up from 175 percent in 1972 (not reported). For primary education the increase was 37.0 percentage points. Surprisingly, there are even interesting results for skilled labor. The college labor content of net imports fell by 3.7 percentage points. The results are the same when oil producers and nonmarket economies are omitted. I do not think that this exercise is rigged to obtain big impacts. I therefore find the conclusions startling.

Can these trade-induced supply changes account for wage trends in the United States? Like a bull in a china shop, let me push forward while deferring discussion of the myriad of caveats. We know the horizontal shift in demand induced by setting the factor content of trade back to its 1972 level [-ΔFT(i) from Table 6-2]. We also know 1992 employment levels [L92(i) from Table 6-2] and have estimates of the elasticities of labor demand εD(i) and supply εS(i). The percentage change in wages induced by changes in the factor content of trade is thus10

Δw(i) EQUIV [w92(i) - w72(i)/w92(i) = [-ΔFT(i)/L92(i)]/[εD(i) + εS (i)]. (8)

Table 6-4 reports the values of Δw(i) for the adjusted factor content calculations, i.e., for the ΔFT(i) given by the Table 6-2 column labeled "net imports, 1992–1972, adjusted." Because elasticities are not known with certainty, I report results for different estimates. The first and third rows are extreme combinations of estimates and provide upper and lower bounds on the wage movements. The middle row elasticity estimates of 0.75 for labor demand and 0.5 for labor supply are more common. In the middle row experiment, changing trade patterns reduce wages of primary education workers by 30 percent and raise wages of college graduates by 5 percent. This 35 percent spread is of the same order of magnitude

TABLE 6-4 Wage Effects of Changing U.S. Trade Patterns

|

Secondary |

|||||||

|

Elasticities |

None |

Primary |

Entered |

Complete |

College |

All |

|

|

Demand |

Supply |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

|

0.50 |

0.10 |

-573 |

-63 |

-8 |

16 |

9 |

-1.9 |

|

0.75 |

0.50 |

-275 |

-30 |

-4 |

8 |

5 |

-0.9 |

|

1.00 |

1.00 |

-172 |

-19 |

-2 |

5 |

3 |

-0.6 |

|

Percentile |

0.7 |

7.7 |

29.8 |

68.1 |

100 |

||

|

NOTE: The table reports 100(w92 - w72)/w92 induced by the 1972–92 changes in the adjusted factor content of net imports. See equation (8). |

|||||||

as that actually experienced by the U.S. economy.11 For reasons discussed below, I do not want to push too hard on this point except to say that it is surprisingly easy to use factor content calculations to partially mimic observed wage changes.12 On the other hand, what I find completely persuasive is the wage effects at the bottom of the education distribution. For the 0.7 percent of the labor force with no education, imports have augmented their supply by almost 170 percentage points and reduced their wage by 275 percent. Imports are devastating the small portion of the work force with little education.

There are a number of issues omitted in this simplistic study. I have not introduced elasticities of substitution between types of labor. Adding this effect diminishes the wage impacts. Nor have I considered labor-capital substitution possibilities. Because net imports of capital have increased by only 0.1 percentage points over the period, trade has not led directly to capital deepening. If capital is a substitute for unskilled labor and a complement for skilled labor, my implicit assumption of zero elasticities leads to overstated wage impacts. Finally, and arguably most important, I ignored the participation decision. As is apparent from the tables, the biggest effect is on those workers who are most likely to be fluidly moving in and out of the labor force. By forcing workers out of the labor force, trade is likely to have significant effects on poverty that are not apparent from wage data.

Trade Versus Immigration as an Explanation of Wage Trends

Borjas et al. (1992) raised the question of whether trade or immigration has been more important in explaining wage trends. Factor content analyses gloss over several facts that are difficult to quantify.

Immigration is a stock whereas trade is a flow. That is, an immigrant arrival increases the stock of immigrants not only in the year of arrival, but also in subsequent years. Trade, or at least nondurable trade, has an impact only in the year it arrives. For example, in 1992 immigration and the labor content of net imports were of comparable magnitudes: 1.0 million immigrants and 1.4 million workers embodied in trade. This is a flow calculation. The stock calculation for

|

10 |

To see this let D92(w72) be the 1992 labor demand schedule evaluated at 1972 wages and shift this demand curve out from the 1992 equilibrium by an amount – ΔFT = D92(w72) - L72 that can be calculated from Table 6-2. To obtain equation (8), start with εD = - [L92 - D92(w72)] / [L92 Δw], substitute out D92(w72) using the expression for -ΔFT, and substitute out L72 using εS = [L92 - L72] / [L92 Δw]. |

|

11 |

This requires an obvious caveat. The bottom of the table reports that the education groups map poorly into percentiles of the U.S. labor force. |

|

12 |

For the unadjusted factor content calculations (i.e., when ΔFT(i) is taken from the Table 6-2 column labeled "net imports, 1992–1972, total"), Δw(i) is tiny for all types of labor except no-education labor where it ranges between 5–17 percent for the Table 6-4 choice of elasticities. Thus, it is the factor content adjustment rather than the elasticities that drives the wage result. |

the period 1972–1992 yields 30 million immigrants compared with a 0.5-million worker change in the labor content of net imports. Thus, immigration would appear to have much greater labor market consequences. Against this must be balanced the fact of assimilation. Over sufficiently long horizons one might want to treat past immigrants as natives.

Immigration has income effects, but without the price-reducing benefits of trade. Import competition has two offsetting effects. It drives down consumer prices (a benefit), and it drives down the incomes of at least some natives (a cost). However, at the point where import competition totally displaces the domestic industry, increased imports have no further negative impact on native incomes. The only effect is beneficial lower consumer prices. This safety valve of comparative advantage specialization is not a feature of immigration. As long as immigrants have skills comparable to those of natives and as long as labor markets are not perfectly segmented along immigrant-native lines, immigrants will compete for native jobs and incomes. When a Mexican arrives in the United States, the impact is felt in every sector where the immigrant is potentially employable. The comparative advantage safety valve suggests that immigration has a more adverse consequence than trade.

Import levels are not indicative of all the potentially harmful labor market consequences of trade. For example, there are cases of foreign firms that do not compete in the U.S. market even though they would if the U.S. product price rose by a small amount. In such contestable markets the possibility of imports constrains the behavior of U.S. firms as tangibly as do realized imports (see also Brander and Spencer, 1981, for a limit-pricing model of trade). None of this is captured by the existing empirical literature, but such a study would lead one to raise the importance of trade relative to migration.

On the other hand, trade has positive welfare implications not captured by the existing empirical work surrounding the trade and wages debate . These are the benefits associated with comparative advantage, specialization, procompetitive effects, dynamic efficiency gains, etc. None of these enter into existing empirical work. The same could be said of the immigration benefits of reunifying families, sheltering refugees, etc., as well as the long-run growth facilitated by immigration. My predilection as a trade economist is to argue that at the margin the unmeasured gains from trade far exceed the unmeasured benefits of migration.

What is the Experiment?

As Leamer (1993) notes, a problem with analysis of the type considered so far is that it is not built around a well-defined policy experiment. Questions about whether immigration is good or trade is bad tend to be overly vague, too grand in conception, and irrelevant to what we care about, namely policy interventions. Like the water and diamond paradox, this leads to confusion between the total

consumer surplus from trade and the marginal consumer surplus created or destroyed by current policy proposals. Total consumer surplus from trade is enormous (imagine a U.S. economy that had not imported journals documenting the British discovery of DNA) but irrelevant to policy. This subsection illustrates the importance of building empirical studies around well-defined policy interventions.

Immigration has a clear policy handle. The level of immigration is controlled through quotas, and the type of immigrant is selected through such criteria as the need for specific skills. Although policy does not fully control immigrant quality and even less so illegal immigration (Hanson and Spilimbergo, 1996), at least there is some possibility for designing policies to affect these outcomes.

In contrast, trade levels are endogenous equilibrium outcomes only partially amenable to policy interventions. The level and composition of trade is less a policy instrument than a vehicle through which policies are transmitted. For example, the run-up of the merchandise trade deficit during the 1980s was not a policy. To the contrary, U.S. trade policy was increasingly protectionist at that time. The deficit at least partly reflected President Reagan's fiscal policies that were totally unrelated to trade (Krugman, 1994). For another example, immigrants promote trade with their country of origin (Baker and Benjamin, 1996) so that trade patterns are to some degree driven by immigration policies!

This raises doubts about the meaning of, among other things, factor content studies. Suppose a trade deficit develops not because of policy interventions but because of falling transport costs and other components of globalization. Because the impact of globalization is not simply a changed U.S. trade pattern, one wonders what the above factor content calculation captures. Consider an assessment of the factor content of trade that explicitly recognizes the multicountry general equilibrium changes associated with globalization. Let L c and Lw denote the supplies of labor in country c and the world, respectively. Let gdpc and gdpw denote gross domestic product in country c and the world, respectively. Under the assumption of consumption similarity, each country indirectly consumes a fraction sc = gdpc/gdpw of the world labor supply. Lc - scLw is the difference between country c's supply of labor and consumption of labor. By definition, this is the factor content of trade. How would one calculate this using input-output tables and trade flow data? Let atgc be the total (in an input-output sense) amount of labor needed to produce one unit of good g in country c. Let Xgc be country c's exports of good g and let Mgc,US be U.S. imports from country c of good g. All the interesting action is with intermediate goods (the bulk of trade flows), so assume that all trade is in intermediate goods. It is tempting to think that

LUS - sUS Lw = Σg{atg,US Xg,US - Σc atgc Mgc,US}, (9)

where one uses country c technology atgc when assessing the factor content of goods produced in country c. However, this turns out to be incorrect because it ignores the impact of globalization on the rest of the world.

As shown in Trefler (1996), the correct equation is

LUS - sUS Lw = Σg {atg,US (Xg,US - Mg,US) - sUS Σcatgc (Xgc - Mgc)}, (10)

where Mgc is country c imports of good g from the rest of the world. From the perspective of the United States alone, national income accounting rules dictate that net exports of intermediate goods are a component of final demand. This explains the equation (10) term Σg atg,US (Xg,US -Mg,US) which is just the usual definition of the U.S. factor content of trade. However, from the perspective of the world as a whole, an intermediate good does not magically become a final good simply by crossing a national boundary. Restated, for the United States alone, net exports are exogenous whereas for the world as a whole net exports are endogenous. The second term on the right-hand side of equation (10) is a correction that accounts for the endogeneity of trade. The choice between equations (9) and (10) depends on whether one wants to treat changes in U.S. trade flows as an exogenous shock or whether one wants to look for a more fundamental international shock that drives U.S. trade flows. For policy analysis, clearly the latter is what matters, and factor content studies based on equation (9) are flawed. In short, one can be seriously misled by failing to clearly articulate the policy environment, including the exogenous shock and the policy instrument.

CONCLUSIONS

We tend to focus on those who lose from immigration to the exclusion of those who benefit. Borjas (1995) used this observation to show that in the short run immigration may yield a net social benefit. Unfortunately, the argument unravels when imbedded in long-run models of international trade. Borjas's immigration "surplus" is zero in the Heckscher-Ohlin model with its factor price equalization theorem. The immigration surplus is negative in the Ricardian model with its negative terms-of-trade effect and industrial "ghettoization" of immigrant labor. To obtain an immigration surplus, an additional kick from immigration is needed as in the increasing returns to scale model with its immigrant externality.

The second half of this chapter had an empirical focus. In light of the dramatic growth in globalization pressures, there is surprisingly little evidence of earnings convergence across countries. This implies that the supply pressures for migration to the United States remain as strong as they were 30 years ago. This appears to hold true even after disaggregating by the level of education of different types of potential immigrants. Another empirical surprise comes from my new factor content study. It indicates that changes in U.S. trade patterns almost certainly battered wages of those at the very bottom of the skill ladder. It also hints at the possibility that, contrary to conclusions of previous research, the changing composition of international trade can explain a large proportion of rising U.S. wage inequality. If so, then trade may be at least as important as immigration in explaining recent labor market trends in the United States. How-

ever, I offered a number of caveats to this last interpretation. Finally, much of the research in this area treats observed changes in equilibrium trade flows as equivalent to the changes one might expect from altering international trade policies. This has led researchers to overstate the importance of trade policy. In contrast, immigration policy is more efficacious in application and should therefore play center stage in policy discussions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to my students at the Harris School for pursuing many of the ideas in this chapter as term papers, to Edgard Rodriguez for data on Filipino migrants, to Huiwen Lai for his research assistance, to Chris Thornberg for data from the 1972 Current Population Survey, and to Michael Baker and Alysious Siow for helpful comments. The third section of this chapter borrows from work in progress with Joe Hotz. George Borjas and Richard Freeman helped frame the questions, and Danny Rodrik helped bring the answers into focus.

REFERENCES

Baker, Michael, and Dwayne Benjamin 1996. "Asia-Pacific Immigration and the Canadian Economy." Pp. 303–347 in The Asia-Pacific Region in the Global Economy: A Canadian Perspective Richard G. Harris, ed. Calgary: University of Calgary.

Barro, Robert J., and Jong-Wha Lee 1993. "International Comparisons of Educational Attainment." NBER Working Paper 4349. Cambridge Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Berman, Eli, John Bound, and Zvi Griliches 1994. "Changes in the Demand for Skilled Labor Within U.S. Manufacturing Industries: Evidence from the Annual Survey of Manufacturing." Quarterly Journal of Economics 109(March):367–397.

Borjas, George J. 1987. "Self-Selection and the Earnings of Immigrants." American Economic Review 77 (September):531–553.

Borjas, George J. 1995. "The Economic Benefits from Immigration." Journal of Economic Perspectives 9 (Spring):1–22.

Borjas, George J., and Valarie A. Ramey 1993. "Foreign Competition, Market Power, and Wage Inequality: Theory and Evidence." NBER Working Paper 4556. Cambridge Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Borjas, George J., Richard Freeman, and Lawrence F. Katz 1992. "On the Labor Market Effects of Immigration and Trade." In Immigration and the Workforce, George J. Borjas and Richard Freeman, eds. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brander, James A., and Barbara J. Spencer 1981. "Tariffs and the Extraction of Foreign Monopoly Rents under Potential Entry." Canadian Journal of Economics 14:371–389.

Card, David, and Alan B. Krueger 1992. "Does School Quality Matter? Returns to Education and the Characteristics of Public Schools in the United States." Journal of Political Economy 100 (February):1–40.

FIGURE 6-A1 Immigration surplus with industry-specific migration. Notes: The figure illustrates the impact of an immigration-induced rise in the industry x specific factor Kx by an amount Δx. A discussion of why industry x labor demand shifts as drawn appears in Dixit and Norman (1980:Figure 2.6). There is one analytic difficulty. Because specific factor rents are not set competitively, it is not clear what portion of industry rents accrue to native rather than immigrant Kx. A sensible assumption is that the division is proportional to the size of the labor demand shift. Then the shaded area is rents that accrue to immigrant Δx. Only the darkly shaded triangle is the immigration surplus. It is positive.

TABLE 6-A1 External Returns to Scale Equilibria

|

Equilibrium |

Diversification Equilibriuma |

Specialization Equilibriuma |

||

|

IRS price (px) |

1/[α(L+L*)] |

βL*/L2 |

||

|

CRS price (py) |

1 |

1 |

||

|

U.S. |

Foreign |

U.S. |

Foreign |

|

|

wages (w) |

1 |

1 |

βL*/L > 1c |

1 |

|

Per capita welfareb |

αα(L+L*)α |

αα(L+L*)α |

β1-α(L*/L)1-αLα |

β-α(L*/L)-αLα |

|

a) In the U.S. diversification equilibrium, the U.S. produces both goods and the foreign country produces only the constant returns (CRS) good. In the U.S. specialization equilibrium, the U.S. produces the increasing returns (IRS) good and the foreign country produces only the CRS good b) β = α/(1 -α). c) The specialization equilibrium only exists when demand for x is too large to be supplied by a single unspecialized country. See Helpman (1984). Mathematically, the equilibrium only exists for α > L/(L+L*) or, equivalently, βL*/L>1. |

||||

TABLE 6-A2 Monthly Wage Differentials for Filipinos Across Selected Countries

|

Males |

Females |

|||||||||

|

US$ |

Philippines = 1 |

US$ |

Philippines = 1 |

|||||||

|

Occupation |

Philippines |

Japan |

Hong Kong |

Singapore |

Saudi Arabia |

Philippines |

Japan |

Hong Kong |

Singapore |

Saudi Arabia |

|

Technical Salesmen & related |

140 |

4.7 |

7.0 |

6.5 |

3.3 |

|||||

|

Transport Equipment Operators |

134 |

2.6 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

2.8 |

103 |

7.6 |

2.9 |

3.4 |

|

|

Housekeeping & related |

117 |

4.7 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

3.7 |

80 |

13.9 |

3.4 |

8.5 |

4.1 |

|

Bricklayers, Carpenters & other construction workers |

111 |

8.1 |

7.9 |

2.9 |

3.3 |

|||||

|

Sales Supervisors & Buyers |

108 |

6.4 |

7.6 |

9.5 |

6.1 |

|||||

|

Chemical Processors & related |

104 |

5.2 |

4.3 |

6.0 |

4.8 |

|||||

|

Blacksmiths, Toolmakers, Machine-Tool Operators |

100 |

5.9 |

6.5 |

6.6 |

4.7 |

|||||

|

Machinery Fitters, Assemblers, Precision Instr. Makers |

99 |

4.1 |

4.3 |

5.3 |

4.4 |

|||||

|

Protective Service Workers |

97 |

2.6 |

4.9 |

4.2 |

||||||

|

Printers & related |

91 |

4.3 |

3.7 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

|||||

|

Plumbers, Welders, Sheet-metal & Structural Metal Prep. |

86 |

4.2 |

5.1 |

4.9 |

4.6 |

|||||

|

Tailors, Dressmakers, Sewers, Upholsterers & related |

82 |

10.0 |

6.9 |

6.7 |

4.9 |

61 |

8.8 |

4.3 |

6.3 |

|

|

Cooks, Waiters, Bartenders & related |

75 |

6.3 |

6.0 |

5.6 |

4.3 |

38 |

16.9 |

9.1 |

10.0 |

|

|

Building Caretakers, Cleaners & related |

69 |

3.5 |

3.4 |

4.1 |

||||||

|

Transport Conductors |

53 |

5.5 |

8.5 |

9.9 |

7.8 |

|||||

|

Launderers, Dry-cleaners & Pressers |

52 |

7.8 |

7.6 |

7.0 |

||||||

|

Fishermen |

38 |

6.9 |

13.7 |

8.5 |

11.0 |

|||||

|

SOURCE: Data were prepared by Edgard Rodriguez. For host countriesdata are from the Philippines Overseas Employment Agency and datefrom the period April–July, 1993. For the Philippines data are fromthe October 1991 Labor Force Survey. Data were converted to currentU.S. dollars using spot exchange rates i.e., there is no PPP correction.The data do not include in-kind transfers such as accommodation. |

||||||||||

Davis, Steven J., and John Haltiwanger 1991. ''Wage Dispersion between and within U.S. Manufacturing Plants, 1963 –1986." Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: Microeconomics 115–180.

Dixit, Avinash K., and Victor Norman 1980. Theory of International Trade: A Dual, General Equilibrium Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dornbusch, Rudiger, Stanley Fischer, and Paul A. Samuelson 1977. "Comparative Advantage, Trade and Payments in a Ricardian Model with a Continuum of Goods." American Economic Review 67 (December):823–839.

Feenstra, Robert C., and Gordon H. Hanson 1996. "Globalization, Outsourcing, and Wage Inequality." American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 86 (May):240–245.

Gaston, Noel, and Daniel Trefler 1994. "Protection, Trade, and Wages: Evidence for U.S. Manufacturing." Industrial and Labor Relations Review 47 (July):574–593.

Gaston, Noel, and Daniel Trefler 1995. "Union Wage Sensitivity to Trade and Protection." Journal of International Economics 39 (August):1–25.

Goldin, Claudia, and Lawrence F. Katz 1996. "Technology, Skill, and the Wage Structure: Insights from the Past." American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 86 (May):252–257.

Hanson, Gordon, and Antonio Spilimbergo 1996. "Illegal Immigration, Border Enforcement, and Relative Wages: Evidence from Apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico Border." NBER Working Paper 5592. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Helpman, Elhanan 1984. "Increasing Returns, Imperfect Markets, and Trade Theory." In Handbook of International Economics, Vol. I, Ronald W. Jones and Peter B. Kenen, eds. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Juhn, Chinhui, Kevin M. Murphy, and Brooks Pierce 1993. "Wage Inequality and the Rise in Returns to Skill." Journal of Political Economy 101 (May):410–442.

Katz, Lawrence F., and Kevin M. Murphy 1992. "Changes in Relative Wages, 1963–1987: Supply and Demand Factors." Quarterly Journal of Economics 107 (February):35–78.

Krueger, Alan B. 1993. "How Computers Have Changed the Wage Structure: Evidence from Microdata, 1984–1989." Quarterly Journal of Economics 1 (February):33–60.

Krugman, Paul 1994. The Aged of Diminished Expectations: U.S. Economic Policy in the 1990s, revised and updated edition. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.