8

Historical Background to Current Immigration Issues

Susan B. Carter and Richard Sutch

Immigration has had a long history in the United States. For the most part, however, it was seldom treated dispassionately even when an attempt was made only to ascertain the pertinent facts and their reliability. Books and innumerable articles were written to "prove" that immigration did not contribute to the population growth of this country because immigration depressed the fertility rate of the native population: that immigration, if it continued, would result in race suicide of the Nordic element; that immigration was a threat to "American" institutions, etc. For this reason much of the literature on the subject is almost worthless.

Simon Kuznets and Ernest Rubin (1954:87)

INTRODUCTION

As background for the work of the Panel on Demographic and Economic Impacts of Immigration, we present a broad overview of the scholarly literature on the impacts of immigration on American life in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

We emphasize at the outset that this is a formidable undertaking. There is an enormous literature on the subject ranging over every conceivable genre. These include nineteenth-century political broadsides, serious and masterfully written histories, the 42 volume report of the first Immigration Commission appointed in 1907, focused cliometric studies appearing in scholarly journals, autobiographies that witness the era of high immigration, two forthcoming economic histories of pre-World War I immigration (Ferrie, 1997; Hatton and Williamson, 1998), obscure statistical compendia, and theoretical analyses some of which are highly abstract and mathematically intricate.

The subject is also emotional and controversial. In the past, as today, immigration policy arouses strong feelings and in some cases these have colored the analysis offered. As Kuznets and Rubin suggested, dispassionate inquiry is hard to find. Many authors express their conclusions with a degree of certitude that is difficult to justify from the evidence they offer. Writers on opposite sides often have failed to take account of the evidence and arguments of their opponents. On

many aspects of the question a modern consensus of scholarly opinion cannot be found.

The economic impact of immigration is a complex issue and one that simple models of supply and demand do not address very well. Indeed, even predictions derived from elaborate general equilibrium models are only as good as the assumed linkages across disparate sectors of the economy. Because of the complexity of the social science, it has become easy for partisans in the debate to ignore scholarly work altogether or to pick and choose studies compatible with their preconceptions from the wide array of findings reported in the literature.

Nevertheless, we believe that it is possible to survey the literature and extract a list of tentative conclusions. These identify rather dramatic differences in the immigrant flows and in immigration's probable impacts between the earlier era of mass immigration and immigration today.

Not everyone will agree with our distillation nor welcome our attempt to cover such an intractable subject with the guise of apparent order. Our "findings" might be better read as provocation for further research. Nevertheless, the process of writing this chapter has convinced us, at least, that this entire area is ripe with important and researchable topics. To encourage debate, we begin by summarizing our findings regarding four interrelated topics.

FINDINGS

The Magnitude and Character of Immigrant Flows

-

Immigrant flows were larger in the past. This is true whether the flows are measured relative to the size of the resident population or to its growth rate.

-

Immigration around the turn of the century was dominated by single males of young working ages. Today's flows include many more women and children.

-

Many of the immigrants during the period of high immigration were sojourner workers who came to the United States to work for a few years and then return to their home country. Today's immigrants are far more likely to be reuniting with family members in this country or to be refugees. Far more than was ever true in the past, today's immigrants come to stay.

-

In the past, immigrant flows were highly responsive to economic conditions in the United States. The numbers swelled when the U.S. economy was booming, wages were rising, and unemployment was low. They ebbed when the economy was depressed. Emigration, the return flow, was highest during American depressions and was reduced during booms. Today the ebbs and flows over time are related to political —not economic—conditions. In particular, some of the largest annual flows in recent years occurred during periods of economic recession in the United States.

-

In the past, America selected people with above-average skills and backgrounds from their countries of origin. Today this pattern still holds for some sending countries, but is less clear for some others.

-

In the past, immigrants took jobs that were concentrated near the middle of the American occupational distribution. There were significant numbers of native-born American workers both below and above the strata occupied by the foreign-born labor force. Today the occupational distribution of immigrants is bimodal, with one group displaying much higher and the other much lower skills than the resident American work force.

Immigration and Economic Growth

Immigration's impact on American economic growth has been the major focus of the scholarship on the previous episode of high immigration. This work suggests that immigration caused the size of the American economy to grow more rapidly than would have been the case in the absence of immigration. The key mechanisms emphasized in the literature are

-

the high labor force participation rate of immigrants;

-

immigration-induced capital flows from abroad, particularly from immigrants' countries of origin;

-

high immigrant saving rates; much of this saving was invested in residential structures and in the capital necessary to operate self-owned businesses;

-

the role of immigration in stimulating inventive activity;

-

the role of immigration in allowing the economy to take advantage of economies of scale; and

-

immigrants' importation of significant stocks of human capital into the United States.

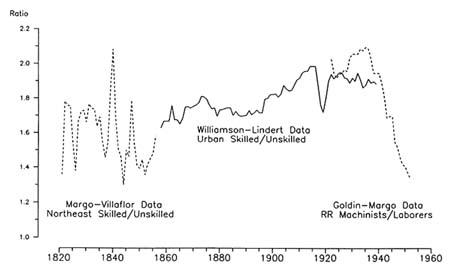

Immigration and the American Income Distribution

Immigration's impact on American income distribution has been much less emphasized in the scholarship on turn-of-the-century immigration. Income inequality appears to have grown over the period of mass immigration, but it is not clear what role immigration played in this development. Key conclusions in the literature are

-

There is no evidence that immigrants permanently lowered the real wage of resident workers overall in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

-

There is no evidence that international immigrants increased the rate of unemployment, took jobs from residents, or crowded resident workers into less attractive jobs.

-

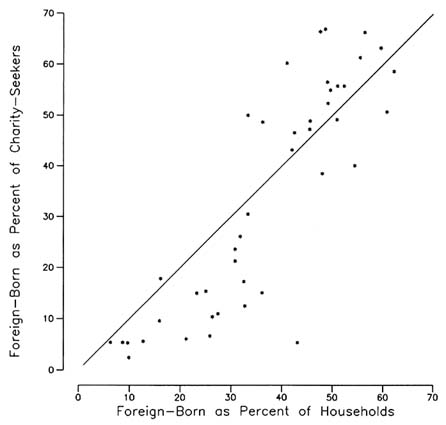

There is no evidence that the early twentieth-century immigrant community placed a disproportionate burden on public charitable agencies or private philanthropies.

-

The turn-of-the-century educational system does not appear to have been

-

an important arena for transferring resources between the foreignand native-born populations.

-

There is some evidence that immigration may have reduced regional differences in income inequality.

On the other hand, there is no consensus regarding the impact of immigration on racial wage differentials. A number of scholars argue that the flow of European-born workers into the rapidly growing industrial cities of the North may have helped to delay the migration of blacks from the South to the North. If it delayed black migration, then immigration from abroad also would have delayed the convergence of black and white incomes.

Immigration and the Character and Quality of American Life

-

There is a broad consensus that immigration did not depress the fertility of the native-born population.

-

The children of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century immigrants appear to have assimilated rather quickly into the mainstream of American life.

THE MAGNITUDE AND CHARACTER OF IMMIGRANT FLOWS

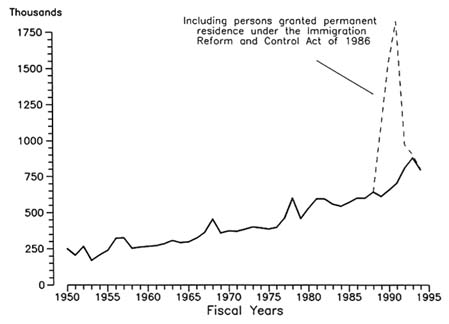

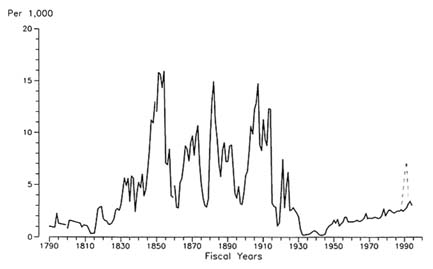

Immigration to the United States has increased steadily in the post-World War II period.1 In 1995, the latest year for which data are available, the number of immigrants admitted into the United States was three times the annual flow between 1951 and 1960 and nearly double that of the 1970s. 2Figure 8-1 displays

|

1 |

''Immigrants" are aliens who have been admitted into the United States for legal, permanent residence. In the post-World War II period, immigrants account for only a small fraction of the total number of aliens who arrive in the United States each year (Bureau of the Census, 1996:Table 7, p.11). In recent years the number of nonimmigrant aliens exceeds the number of immigrants by approximately twentyfold. Note that the data on nonimmigrants count arrivals rather than individuals so a person making multiple visits would be counted once for every visit. The overwhelming majority of these nonimmigrants are tourists, business travelers, and people in transit. Students are another important category of alien nonimmigrants. The number of alien nonimmigrant student arrivals each year is about half as great as the total number of people admitted as immigrants. Over the past ten years the number of temporary workers and trainees has grown very rapidly to become another important category of alien nonimmigrants. In 1995, the latest year for which data are available, the number of temporary workers admitted was almost as great as the number of students. Illegal border crossers, crewmen, and "insular travelers" are a third category of aliens who enter the country. They are not included in any of the totals reported here. |

|

2 |

The number of immigrants admitted in 1993 was 880,000 exclusive of those admitted under the legalization adjustments permitted by the IRCA. The number of immigrants admitted during the years 1951 –1960 was 2.5 million and between 1971 and 1980 it was 4.5 million (Bureau of the Census, 1996: Tables 5 and 6, p.10). |

|

3 |

These are the "official" numbers as published by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service in its annual Statistical Yearbook (1997:Table 1, p. 27). Also see Bureau of the Census (1975/ 1997, series C89; 1996:Tables 5 and 6). |

FIGURE 8-1 Immigrants to the United States, 1950–1995.

the number of legal immigrants arriving in the United States annually between 1950 and 1995.3 The spike in the graph for the years 1989 through 1992, shown by the dashed line, includes persons granted permanent residence under the legalization program of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986. Even excluding these "special" immigrants, the figure shows a pronounced upward trend in immigration over the last third of the century. Moreover, if the response to the IRCA can be interpreted as some measure of the "excess supply" of potential immigrants, then the pressure on American borders may have grown much faster than the numbers plotted in Figure 8-1 would suggest.

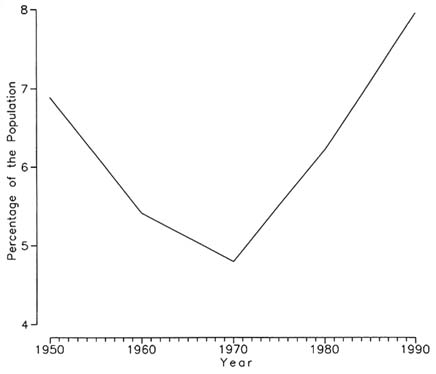

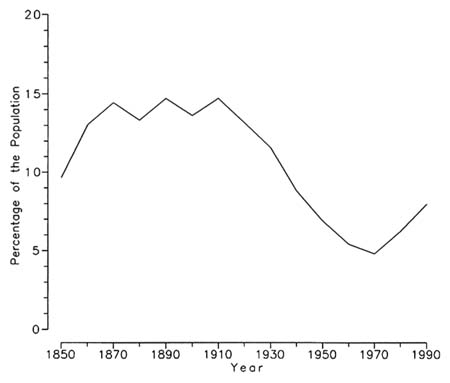

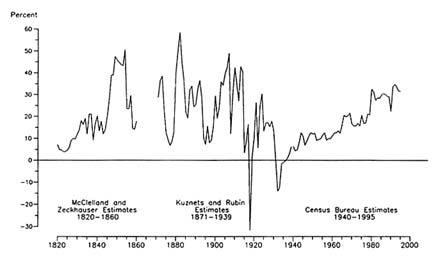

As a direct consequence of the recent increase in immigration, the fraction of the American population that is foreign born has risen dramatically. Figure 8-2 charts this change for the post-World War II period.4 In the 1950s and 1960s, the small number of immigrants, together with the high fertility of the native population, meant that the fraction of the population that was foreign born actually declined. In 1950 the foreign born comprised 6.9 percent of the population; by 1970 their share had dropped to only 4.8 percent. The increasing numbers of immigrants after 1970 led to a reversal of this downward trend. By 1990 the foreign born had surpassed their 1950 share, accounting for 7.9 percent of the

|

4 |

Bureau of the Census (1975/1997, series A91; 1990:Table 253; 1993:Table 1). |

FIGURE 8-2 Foreign born as a percentage of the U.S. population, 1950 –1990.

population. A recent news release by the Census Bureau puts the 1996 share at 9 percent.

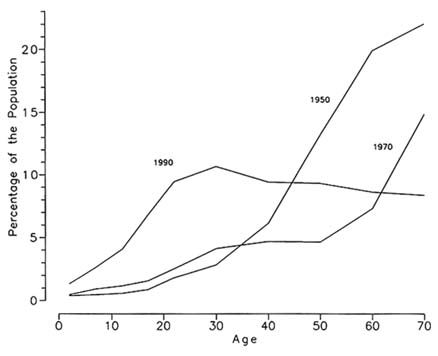

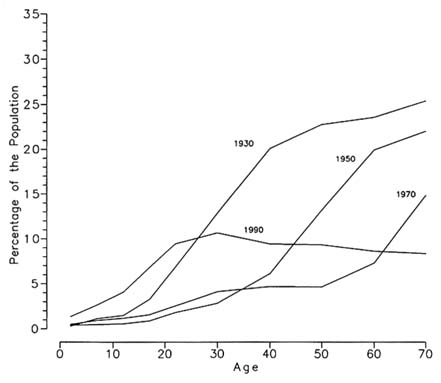

Because immigrants tend to be young adults, the recent increase in immigration has had a disproportionate impact on the population in the age range of 20 to 40 years. This is shown in Figure 8-3, which plots the fraction of the foreign-born population by age at three post-World War II census dates.5 In 1950, and even more so in 1970, the foreign born tended to be older than the average American. These people had migrated to the United States in the early decades of the century when they were in their late teens and early twenties. By the post-World War II period, they had aged, but the long period of reduced immigration beginning in the 1920s and lasting through 1970 meant that there were far fewer new recruits at the lower end of the age spectrum. The resumption of heavier immigration in the 1980s and 1990s substantially altered the age structure of the foreign-born population. Because the new immigrants were disproportionately

|

5 |

Bureau of the Census (1975/1997, series A119-A134; 1984:Table 253; 1993:Table 1). |

FIGURE 8-3 Foreign born as a percentage of the U.S. population, 1950, 1970, and 1990.

young adults, their arrival increased the foreign-born fraction of the population in the economically active age groups. It is no wonder that the current policy debate over immigration centers on labor market and employment impacts (Borjas, 1995).

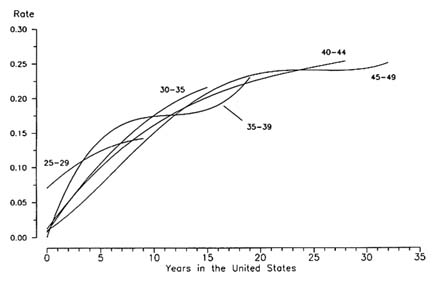

Current Flows in Historical Perspective

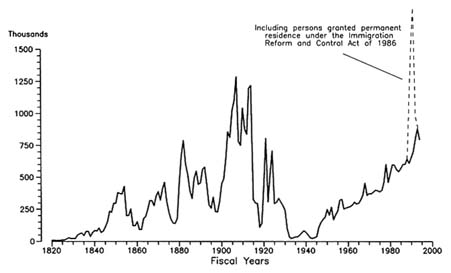

The level of immigration in the 1980s and 1990s is certainly high in the context of the immediate post-World War II decades—and, indeed, in the experience of almost all of the native-born population of the United States today. Yet it is relatively modest from the perspective of the experience in the period 1880–1914, the era of "mass immigration." Figure 8-4 displays the numbers of immigrants admitted into the United States over the period 1820–1995. This is the same series as the one displayed in Figure 8-1; Figure 8-4 presents this series over

|

6 |

These are the "official statistics" of immigration which are the result of the Passenger Act of March 2, 1819, that required the captain of each vessel arriving from abroad to deliver a manifest of all passengers taken on board in a foreign port, with their sex, age, occupation, country of origin, and whether or not they intended to become inhabitants of the United States. These reports were collected and abstracted for the period 1820–1855 by Bromwell (1856/1969), for the period 1820–1874 by the Secretary of State, for the period 1867–1895 by the Treasury Department's Bureau of Statistics, and since 1892 by the Office or Bureau of Immigration which is now part of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (1997). The statistics for the period 1820–1910 were compiled by the U.S. Immigration Commission (1911:Volume 1, Table 1, p. 56). The defects of the official series are well known (Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, 1975/1997:97–98, series C89; Jerome, 1926:29–33; Kuznets and Rubin, 1954:55–64; Hutchinson, 1958; Thomas, 1954/1973:42–50; McClelland and Zeckhauser, 1983:32–35; and Schaefer, 1994:55–59). The chief biases are the following: (1) the figures apparently exclude first-class passengers for the early decades, (2) they may include some passengers who died en route, (3) before 1906 they exclude immigrants arriving by land from British North America (Canada) and Mexico, (4) immigrants arriving at Pacific ports before 1849 and at Confederate ports during the Civil War are excluded, and (5) the data measure gross rather than net immigration. Despite these imperfections the official series is thought to measure gross flows reasonably well. |

FIGURE 8-4 Immigrants to the United States, 1820–1995.

a longer period of time.6 Although the spike of 1991, reflecting the response to the IRCA, still stands out, the chart reveals that the number of immigrants admitted through normal channels in the recent period is decidedly smaller than the number admitted in the first decade of the twentieth century.

Moreover, the United States was a much smaller country early in the century. To put the current immigration flows into proper perspective, we deflate the numbers of immigrants by the number of people resident in the United States at

|

7 |

The data in Figure 8-5 have been extended back to 1790, and the data before the Civil War have been corrected for the undercounts noted in footnote 6. The figures for 1790–1799 are from Bromwell (1856/1969:13–14) and should be considered as nothing more than educated guesses by contemporaries Blodget (1806/1964) and Seybert (1818). The data for 1800–1849 are estimates made by McClelland and Zeckhauser (1983:Table A-24, p. 113). Those for 1850-1859 are estimates by Schaefer (1994:Table 3.1, p 56). Thereafter the official statistics from the U.S. Immigration and Naturce are used (1997:Table 1, p. 27). The resident population is taken from Bureau of the Census (1975/1997, series A7; 1996:Table 2, p. 8). |

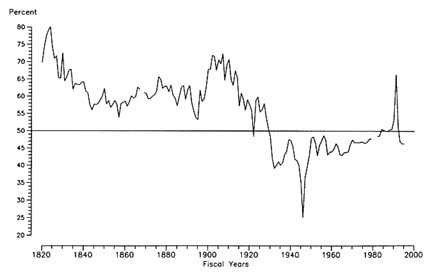

FIGURE 8-5 Immigrants to the United States, 1790–1990 (per thousand of resident population).

the time of the immigrants' arrival and display the result in Figure 8-5.7 Our calculations reveal that, in proportionate terms, the current inflow of immigrants is rather modest. If we look only at the "regular" immigrants—that is, exclusive of those admitted under the IRCA—then the current inflows approximate those in the very slowest years from the period between 1840 and the onset of World War I. Before the imposition of a literary test for admission in 1917 (overriding President Wilson's veto) and the passage of the Emergency Quota Act in May 1921, only the disruptions of World War I pushed the flow of immigrants relative to the native population to levels below the relatively low levels that we experience today.8

Immigration as a Source of Population Change

As a consequence of the large and persistent immigrant flows in the 1845–1914 period, the foreign born came to comprise a rather large fraction of the total population. Figure 8-6 shows that, in the years between 1860 and 1920, the number of resident Americans born abroad ranged between 13 and 15 percent of the total population (Bureau of the Census, 1975/1997, series A91). The foreign-born

|

8 |

Goldin (1994) discusses the legislative and political history of immigration restriction. |

FIGURE 8-6 Foreign born as a percentage of the U.S. population, 1850 –1990.

born fraction of the population in that period was approximately three times the level recorded in 1970 and over one and one-half times as high as it is today.

The historical record thus reveals that the numerical impact of immigration flows were once substantially larger than what we have now and were also larger than the levels we are likely to experience in the foreseeable future. Thus we are tempted to suggest that the economic and demographic consequences of immigration in the 1845–1914 period are likely to have been greater than the impact of immigration flows today.

Yet any comparative analysis should explicitly incorporate at least three ways in which the situation today is different from that of the era of mass immigration. First, the structure of the economy and labor market have changed. Some would say the structure is both more complex and less flexible and that labor markets are more segmented. Second, the government is a much larger entity both in terms of the resources it consumes and the fraction of national income it reallocates through tax and transfer mechanisms. Third, immigration is now regulated. We return to these points later in this chapter.

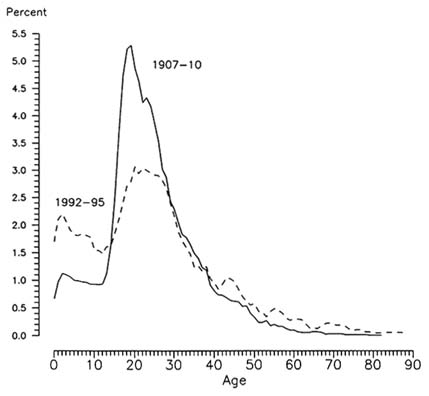

FIGURE 8-7 Age distribution of immigrants to the United States, 1907 –1910 compared with 1992–1995.

Age and Gender of Immigrants

The overwhelming proportion of immigrants are young adults. This is true today and it was so in the early years of the twentieth century as well. Figure 8-7 contrasts the age distribution of immigrants in 1907–1910 with that for immigrants in 1992–1995.9 Clearly, the propensity to immigrate is strongest from

|

9 |

The data for 1909–1910 are based on the Public Use Microdata Sample from the enumerator's manuscripts for the 1910 population census. We use the version of this sample that was prepared in a way that improves their comparability with census samples from other years. This file is known as the Integrated Public Use Microdata Sample or IPUMS (see Ruggles and Sobek, 1995). All immigrants (both males and females) who reported arriving in the United States in 1907 or after were included (n = 7658). This census was taken on April 15, 1910. The sample thus includes all 1907–1909 immigrants and slightly more than one-fourth of the 1910 arrivals. The 1992–1995 data are based on the March Current Population Surveys, or CPS, of the Bureau of Labor Statistics for 1994 and 1995. They include all immigrants who reported a permanent move to the United States during or after 1992. All migrants residing in the United States in 1994 or 1995 who immigrated in 1992–1994 and the first few months of 1995 are included (n = 3841). |

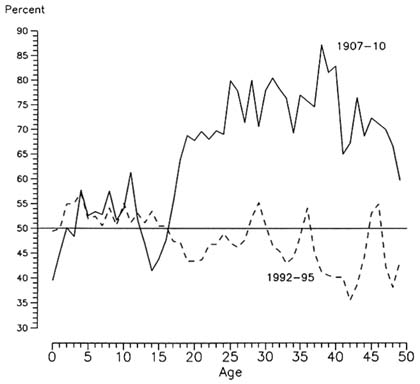

ages 18 to 30 in both periods. One change that is visible is that modern immigrants are more likely to be accompanied with young children than was true in 1907–1910. This finding is understandable in terms of the reduced costs of migration but it also reflects a sharp change in the gender composition of immigrants. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries men were far more likely to come to America than women. This gender imbalance was particularly pronounced among the young adults who constituted the bulk of all immigrants.

Figure 8-8 contrasts the data on gender composition of immigrants by age from the 1907–1910 period with the most recent data available on gender composition. The proportion male was well over 70 percent in the age range 18–40 in 1907–1910. This represents a male-female ratio of more than two to one. For those in their late twenties, the ratio is greater than three to one. The data from the beginning of the century, when the age of independence was younger than today, show a modest imbalance in favor of young women aged 12–16, undoubtedly produced by the earlier maturation of girls than boys. yet the startling

FIGURE 8-8 Proportion of immigrants to the United States who are male, 1907–1910 compared with, 1992–1995.

FIGURE 8-9 Proportion of immigrants to the United States who are male, 1810–1990.

finding revealed by Figure 8-8 is the relative gender, equality in immigration in the modern data. Today women actually predominate in the prime migration age cohorts.

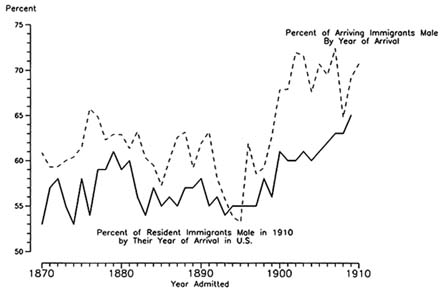

The data on the gender of immigrants are available beginning in 1820. 10 The long time series of the proportion male is plotted in Figure 8-9. The predominance of males is clearly a phenomenon of the entire period of uncontrolled immigration but it disappears within a decade following the imposition of limitations in 1921. The spike in 1991 shows the impact of the IRCA, which facilitated the transition to immigrant status of certain illegal alien residents.

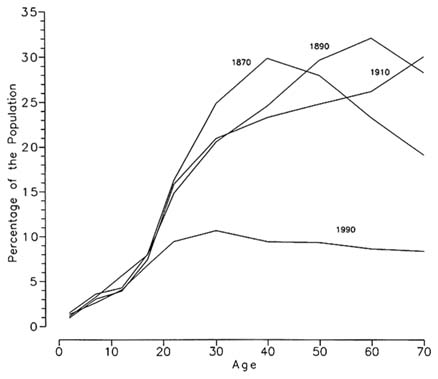

The age selectivity of migration and the size of the annual flows affect the age composition of the foreign-born population. Figure 8-10, which displays the fraction of the foreign-born population by age for selected census years beginning in 1870 (Bureau of the Census, 1975/1997, series A119-134), shows that persons resident in the United States at the turn of the century were in the prime working age groups. Although the overall fraction of the foreign-born population in the earlier period was about twice the percentage for 1990 (Figure 8-6), the fraction in the prime working ages was close to three times as great as today. It is no wonder that the first U.S. Immigration Commission (1911) concentrated its attention on the impact of immigration on the labor market and employment.

|

10 |

Census Bureau (1975/1997, series C138-C139); U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (1979:Table 10, p. 27; 1990:Table 11, p. 24; 1997:Table 12, p. 54). Official data on gender are not available for 1868, 1980, or 1981. |

FIGURE 8-10 Foreign born as a percentage of the U.S. population, selected census years.

Return Flows: Sojourners or Permanent Residents?

The literature on the mass migration in the early part of this century emphasizes the role of sojourners who moved to the United States for a temporary period to earn income, accumulate assets, and then returned to their home countries (Baines, 1985, 1991; Wyman, 1993). These temporary migrants in the earlier era bear some similarities with the ''guest workers" in today's Europe or the Braceros of the southwestern United States during the early postwar era.11 Quite possibly, recent illegal immigrants to the United States should be thought of more like these early twentieth-century sojourners than as individuals intending to settle permanently—albeit illegally —in this country (Warren and Kraly, 1985).

|

11 |

The Braceros program was established during World War II to relieve wartime shortages in the agricultural labor markets of Southern California and Texas. These migrant workers were allowed to remain in the United States for up to 18 months. The program was extended after the war and was not ended until 1965 (Feliciano, 1996). |

FIGURE 8-11 Proportion of the foreign born in 1910 who were male according to year of arrival compared with proportion of foreign born who were male at various arrival years.

The magnitude of the actual return flows are difficult to measure with precision, yet all of the evidence we have been able to assemble suggests that the return flows were quite large. For example, we think it is interesting to note that, while the age composition of the immigrants had a strong impact on the age distribution of the subsequent foreign-born population, the proportion of males among the foreign-born population recorded at the various censuses from 1880–1910, although greater than 50 percent, was not heavily imbalanced. In Figure 8-11 we make use of the 1910 IPUMS (Ruggles and Sobek, 1995) to calculate the proportion of foreign-born males in 1910 according to their year of arrival in the United States. These numbers are compared with the proportion of immigrants arriving in each year who were male (dashed line).12 The farther the distance back in time from 1910, the smaller the male share among those who arrived in the year and who remained in the United States as compared with the male share among arrivals in that year. Clearly many more male then female immigrants returned to their homelands with just a brief stay in the United States.

Another clue regarding the relative importance of sojourners in the earlier immigrant flows is contained in the time series displayed in Figure 8-9. There,

|

12 |

The immigration data are the same as displayed in Figure 8-9 except that calendar year flows are estimated by averaging the fiscal year data. That is, calendar year 1905 is an average of fiscal year 1905 (which ends June 30, 1905) and fiscal year 1906. |

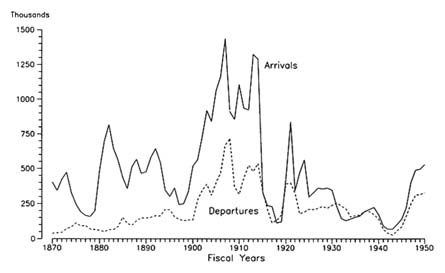

FIGURE 8-12 Alien passenger arrivals and departures 1870–1950.

the predominance of males among new immigrants declines during periods in which the economy was depressed—1857, 1874–1876, 1894–1895, 1920–1921—precisely the same periods when the number of immigrants declined. This cyclical pattern to the male share is consistent with the hypothesis that male immigrants were primarily sojourners whose migration decisions were quite sensitive to economic conditions in the United States.

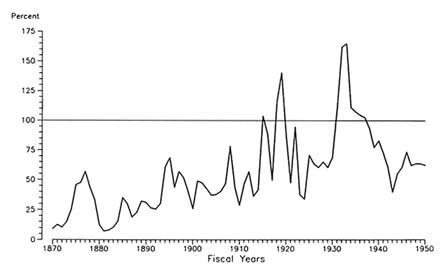

Certainly it is plausible that a depressed economy would discourage sojourners. But in fact little is known about the phenomenon in the era of mass migration. Before 1908 the official statistics count only arrivals. They do not distinguish between permanent settlers and temporary guest workers, nor is there any comprehensive count of returning immigrants during this period. Kuznets and Rubin (1954: Table B-1, pp. 95–96) have estimated return migration for the period 1870–1908 based on official reports of passenger departures and several assumptions about the mix of American citizens and returning immigrants in the departure data, the mortality of foreign born in the United States, and the mortality of Americans when visiting abroad.13 The Kuznets and Rubin estimates are displayed in Figure 8-12 together with the official departure data from 1908 onward. We have also reproduced the official figures on arrivals in Figure 8-12. This is the same series as the one displayed in Figure 8-4. Figure 8-13 displays what we call the "immigrant return rate." It is the number of departures each year expressed as a percentage of arrivals.

|

13 |

These data from Kuznets and Rubin have been accepted by Hatton and Williamson (1998), who use them for calculating annual estimates of net migration. |

FIGURE 8-13 Immigrant return rate (departures as a percent of arrivals).

Figure 8-13 shows that the return rate rose from less than 10 percent in 1870 and 1881 to over 70 percent just before World War I. This increasing propensity of the United States to attract sojourners makes sense given the declining cost of transatlantic passage due to the continual technological improvement of the steamship following the introduction of scheduled service on the North Atlantic in the 1860s (Baines, 1991:40–42).

Immigration and the American Business Cycle

If we return to Figure 8-4, we find that it reveals another striking difference between the data for the recent and the distant past. In the recent past, immigration flows have increased in almost every year, showing little sensitivity to year-to-year changes in macroeconomic conditions. This is because immigration is today closely regulated and because more wish to migrate than the number of visa slots available. Most successful immigrants have been waiting for admission for several years. Today, year-to-year changes in the number of immigrants reflect policy changes, particularly regarding the admission of refugees and asylees, not changes in demand for admission. In the early period, by contrast, immigration was extremely sensitive to economic conditions in the United States. Between 1891 and 1895, for example, when the unemployment rate almost doubled from 4.5 to 8.5 percent, the number of immigrants fell by more than half, from 560,000 to 259,000. Even more dramatic is the almost 40 percent reduction in the number of immigrants in a single year, from 1.3 million 1907 to 783,00 in 1908 in

response to a sharp jump in the unemployment rate from 3.1 to 7.5 percent between those same years (Bureau of the Census, 1975/1997, series C89; Weir, 1992:341). Jerome (1926:208) concluded that the lag between economic activity and immigration in this period was only one to five months.

The relationship between the American business cycle and the flow of immigrants has been examined extensively (Jerome, 1926; Thomas, 1954/1973; Abramovitz, 1961; Williamson, 1964; Easterlin, 1968). The consensus is that the pull forces of American opportunities dominated the push forces of European poverty, land scarcity, and military conscription (Easterlin, 1968:35–36; Cohn, 1995). Thomas (1954/1973) has developed an elegant model of the "Atlantic economy" as an integrated economic unit with flows of immigrants, goods, and capital moving in a rhythm of self-reinforcing and inversely related long-swing Kuznets cycles.14 This raises the possibility that immigration acted as a "governor" for the economy, slowing down the booms and cushioning the depressions. Early writers on the business cycle such as Mitchell did not believe that immigration was likely to have been a major factor in moderating the cycle (1913:225–228). Jerome on balance thought immigration may have exacerbated depressions, but his conclusion drew a strong rejoinder from Rorty.15 More recent work on the business cycle tends to ignore the role of immigration, perhaps for the obvious reason that the cyclical nature of the immigration flows ended with the Quota Act. However, Thomas (1954/1973) and Hickman (1973) have both suggested that the reduction in immigration was responsible for the decline in demand for housing that preceded and may have contributed to the Great Depression.

It was not just the inflow of immigrants that responded to economic conditions in this country; the outflow of emigrants also responded to the rate of unemployment. Figure 8-13 shows large increases in the rate of departure during the business downturns after 1873, in 1885, after 1893, and in 1908. Throughout the period preceding World War I, the inward and outward movements of immigrants show a negative correlation.16 In 1910 and 1913, when arrivals are up, departures are down. In 1912, when arrivals are down, departures are up. The relationship changes with the onset of the war. Both arrivals and departures are down during the war years and up during the immediate postwar period.

|

14 |

Fishlow (1965:200–203) has expressed doubts about the Thomas model. |

|

15 |

Jerome (1926:120–122) was impressed by the fact that net immigration was positive even during times of depression (he was writing before the Great Depression). Rorty, who as a Director of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) by appointment of the American Statistical Association, had the right to attach a dissenting footnote to Jerome's NBER Occasional Paper, correctly, we think, pointed out that the cause of the growth rate in the population should be irrelevant to population growth's impact on the business cycle. Because immigration flows slowed during business downturns, the cyclical movement of immigration can only have helped reduce the magnitude of the unemployment problem. |

|

16 |

However, a glance at Figure 8-12 reveals that the magnitude of changes in departures is much smaller than that for arrivals. |

Kindleberger (1967), commenting on the European economy in the post-World War II period, has emphasized the potentially important role that sojourners might play in moderating the business cycle. In the upturns an elastic labor supply from abroad might relieve bottlenecks, moderate wage increases, and thereby extend an expansion. In downturns an elastic labor supply can reduce downward pressure on the wage rates earned by the resident population and reduce the drain on public coffers for support of the unemployed. Recently, Hatton and Williamson (1998) have revived the issue of the role of sojourners in moderating the consequences of economic fluctuations in the United States. They compare the actual course of the business cycle of the 1890s with a "no-guest-worker counterfactual" and conclude that the impact of guest workers on moderating the business cycle was "surprisingly small." This assessment is based on their finding that "free migration muted the rise in unemployment during the biggest pre-World War I depression, 1892 to 1896, by only a quarter." Size, of course, is in the eye of the beholder. Some would judge this effect as gratifyingly large. Clearly, an important area for further research would be to improve our understanding of the impact of the sojourner on the American economy at the turn of the century, especially in light of the possibility that illegal migrants might be playing a similar role in the American economy today.

The Question of Immigrant "Quality"

Although it is probably an unfortunate term, the historical literature has given considerable attention to the issue of immigrant "quality." Simply put, the question is whether the United States attracted the more-highly skilled, the more entrepreneurial, and the more adventurous from abroad, or whether it received the "tired, … poor, your huddled masses," the unlucky, the least educated, and the least able?17 Presumably, "high-quality" immigrants would accelerate economic growth, vitalize and enrich the society, and more quickly assimilate into the American "melting pot.'' "Low-quality" immigrants would, it has often been charged, be more likely to become a burden on the economy, exacerbate inequality, and prove to be a disruptive social force.

In 1891 Francis Walker, the first President of the American Economic Association and former Superintendent of the U.S. Census, expressed his opinion on the matter with little generosity:

[N]o one can surely be enough of an optimist to contemplate without dread the fast rising flood of immigration now setting in upon our shores. …[T]he

|

17 |

Recall the poem by Emma Lazarus inscribed at the base of the Statute of Liberty: Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest tossed to me: I lift my lamp beside the golden door. |

immigration of the present time … is tending to bring to us no longer the more alert and enterprising members of their respective communities, but rather the unlucky, the thriftless, the worthless. … There is no reason why every stagnant pool of European population, representing the utterest failures of civilization, the worst defeats in the struggle for existence, the lowest degradation of human nature, should not be completely drained off into the United States. So long as any difference of economic conditions remains in our favor, so long as the least reason appears for the miserable, the broken, the corrupt, the abject, to think that they might be better off here than there, if not in the workshop, then in the workhouse, these Huns, and Poles, and Bohemians, and Russian Jews, and South Italians will continue to come, and to come by millions (Walker, 1891, as quoted in Handlin, 1959:73–74).

Treatment of immigrant "quality" is intimately bound up with the pull versus push debate about the motives underlying immigration. If immigrants were pushed out of their home country by increasing immizeration, lack of jobs, or shortage of land, the presumption is that immigration would tend to select individuals from the lower tail of the skill and resourcefulness distributions of their country of origin. On the other hand, if immigrants were pulled to the United States by the attractiveness of American opportunities, they are more likely to come from the upper tail of the home country distribution. 18

Did Migration Select the Best from Europe?

Whether looked at from the point of view of the attributes of the arrivals or the push versus pull controversy, the consensus among economic historians is that, before World War I, America selected immigrants from the upper tail of the

|

18 |

Historical studies of immigration debate the relative importance of these "push" and "pull" forces. We note that the differential selectivity of push and pull forces is not a certainty. The push view is based on a threshold model in which low incomes in the origin country depress incomes in the lower tail of the income distribution below some intolerable poverty line. This is thought to compel the migration of the most wretched. Those more fortunately situated are thought to want to remain. Those critical of the push view note that the very poor do not have the resources to afford long-distance migration. This emphasis moderates or even reverses the conclusion that push works to select the least able and least skilled. The pull model assumes that those with the highest ability and the most education will have the most to gain by transferring their skills to a country with a higher capital-labor ratio and a stronger growth-induced excess demand for skilled workers. This conclusion is not a certainty, either. Perhaps the highly skilled can earn more at home in a poor country or perhaps their relative income position matters most to them. If so, they would prefer to be a big fish even if they have to live in a small pond. The recent literature on the selectivity of immigration in the modern period makes heavy use of a different model of selectivity developed by Roy (1951). For an application to modern immigration patterns see Borjas (1987, 1994). The Roy model focuses on differences between countries in the variance of their earnings distributions as well as in the mean. Countries with a large variance in earnings tend to select immigrants from the upper tail of the earnings distribution in sending countries; the reverse is true for countries with small earnings variance. |

skill distribution in their countries of origin (Easterlin, 1971; Dunlevy and Gemery, 1983). Mokyr (1983:247–252), for example, has studied the occupations of Irish immigrants before 1850 and concluded that immigration selected from the upper tail of the occupational distribution of Ireland, although the magnitude of the difference between the occupational mix of immigrants and that of the resident population of Ireland was small.19 Authors who emphasize the pull of American opportunities suggest that these forces would select the higher-skilled, better-situated members of European society. Even Thomas (1954/1973: 56–62), one of the relatively few writers who sees a strong role for push factors in motivating immigration, agrees that migrants to the United States tended to come from the upper strata of their own societies.

How Did Immigrants Compare with Native-Born Workers?

Whether these select workers from Europe's perspective appeared as high-skilled and advantaged competitors in the American labor market is more controversial. It could be true that immigrants selected from the upper tail of their home country's distribution of skills and other endowments nevertheless fell below the median of native-born American workers. It has also been asserted that the quality of immigrants fell as mass migration continued. A popular textbook in economic history states that "It is probably true that immigrants after 1880 were less skilled and educated than earlier immigrants."20

Historians have sometimes asserted or assumed that the bulk of immigrants were unskilled.21 Handlin (1951/1973:58, 60) in the classic history of immigration to America, The Uprooted, described immigrants as "peasants," people who lacked training for merchandising and the skills to pursue a craft. This view also appears in some surveys of American history. The textbook by Nash et al. (1986:604), for example, reports that "most immigrants" after the Civil War "had

|

19 |

Others who have reached similar conclusions include Baines (1985:51 –52), Erikson (1972, 1981, 1989, 1990), and Van Vugt (1988a, 1988b). Cohn (1992, 1995) has criticized this work for using biased samples that underestimated the numbers of laborers and farmers in the years before the Civil War. The issue is how to treat the "questionable" passenger lists. These are lists on which every passenger is recorded as a laborer (or farmer) usually by the use of ditto marks down the occupation column. Most researchers have excluded such lists from their samples. Cohn disagrees. When Cohen includes the questionable lists in his sample, he finds more laborers and farmers among immigrants from England and Scotland and more laborers and servants from Ireland than in the occupational distributions of the countries of origin. In the case of Germany, on the other hand, Cohn's work supports the select immigrant hypothesis. |

|

20 |

Walton and Rockoff (1994:402). This exact sentence has passed down to this edition of the textbook from Robertson (1973:387) through Walton and Robertson (1983:444). None of these texts offers a citation or evidence. |

|

21 |

The proposition advanced in this literature is that the immigrants arrived without skills acquired in their home country. This is somewhat different from asserting that immigrants took unskilled jobs in this country regardless of their ability to perform skilled work. |

few skills." Cliometric investigation suggests a quite different story. Available evidence implies that skill differences between native- and foreign-born workers throughout the period of mass immigration were small or nonexistent and that the relative quality of immigrants did not fall over time.

Occupations of Arriving Immigrants

One source of evidence on the relative skills of newly arriving immigrants are the ship manifests giving the occupation of arriving passengers, recorded since the United States began the formal collection of immigration statistics in 1819. These data have been compiled by broad occupational grouping in Historical Statistics of the United States (Bureau of the Census, 1975/1997, series C120–137) and by more detailed occupations for 1819–1855 in Bromwell (1856/1969). Table 8-1 displays the occupational distribution of immigrants who reported an occupation at the time of their arrival into the United States according to broad occupational categories. Figures are presented as decadal averages for the 50-year period 1861–1910. The high proportion of immigrants describing themselves as unskilled laborers in the passenger lists (40–50 percent before 1900) seems to suggest that the skill content of immigration during this period was low. At the same time, farmers and agricultural workers are not particularly evident. They are certainly proportionately less evident in the immigrant flows than in the resident American labor force.

Table 8-2 compares Lebergott's (1964) estimates of the percentage of the resident labor force in the agricultural sector over the 50-year period beginning in 1861 with comparable data on the occupations of arriving immigrants presented

TABLE 8-1 Occupation Upon Arrival to the United States for Immigrants Reporting an Occupation, 1861–1910

|

Decade |

Total |

Agriculture |

Skilled Labor |

Unskilled Labor |

Domestic Service |

Professional |

All other Occupations |

|

1861–1870 |

100.0 |

17.6 |

24.0 |

42.4 |

7.2 |

0.8 |

8.0 |

|

1871–1880 |

100.0 |

18.2 |

23.1 |

41.9 |

7.7 |

1.4 |

7.7 |

|

1881–1890 |

100.0 |

14.0 |

20.4 |

50.2 |

4.9 |

1.1 |

9.4 |

|

1891–1900 |

100.0 |

11.4 |

20.1 |

47.0 |

5.5 |

0.9 |

15.1 |

|

1901–1910 |

100.0 |

24.3 |

20.2 |

34.8 |

5.1 |

1.5 |

14.1 |

|

NOTE: The category "All Other" consists primarily of managers, sales and clerical workers, and self-employed proprietors and merchants. SOURCE: Ernest Rubin. "Immigration and the Economic Growth of theU.S.: 1790–1914." Conference on Income and Wealth. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1957: 8. As reportedin Elizabeth W. Gilboy and Edgar M. Hoover. "Population and Immigration.''In Seymour E. Harris, ed., American Economic History. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961, table 7: 269. An obvious error inthe Domestic Service column for the last three decades has been corrected. |

|||||||

TABLE 8-2 Agricultural Occupations as a Percentage of All Occupations in U.S. Work Force and the Percentage of Immigrants Reporting an Agricultural Occupation Upon Arrival, 1860–1910

|

Decade |

Agriculture Occupations as a Percentage of United States Work Force |

Percentage of Immigrants Reporting an Agricultural Occupation Upon Arrival |

|

1861–1870 |

52.7 |

17.6 |

|

1871–1880 |

51.8 |

18.2 |

|

1881–1890 |

46.4 |

14.0 |

|

1891–1900 |

41.3 |

11.4 |

|

1901–1910 |

35.2 |

24.3 |

|

NOTE: The figures on agricultural occupations as a percentage of the resident U.S. workforce are averages of data for the two census years that span each decade. That is, the figure for 1861–1870 averages the data for 1860 and 1870. SOURCES: Occupations of the U.S. workforce: Stanley Lebergott. Manpower in Economic Growth: The American Record Since 1800. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964, table A-1: 510. Occupations of arriving immigrants: Ernest Rubin. "Immigration and the Economic Growth of the U.S.:1790–1914." Conference on Income and Wealth. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1957: 8. As reportedin Elizabeth W. Gilboy and Edgar M. Hoover. "Population and Immigration."In Seymour E. Harris, ed., American Economic History. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961, TABLE 7: 269]. An obvious error inthe Domestic Service column for the last three decades has been corrected. |

||

from Table 8-1.22 In no decade is the proportion of agricultural workers in the immigrant flow over 25 percent; in no decade is the proportion of agricultural workers in the American labor force less than 35 percent. Because farmer and agricultural occupations are generally classified as unskilled, this evidence implies that a large fraction of the American labor force was also unskilled in the nineteenth century. The high proportion of laborer occupations among the arriving immigrants cannot support the suggestion that new immigrants were less skilled than the average resident worker.

Also, immigrants do not appear to have been particularly deficient in skills as compared with the nonagricultural labor force in the United States. Table 8-3 makes the comparison for the first decade of the twentieth century, the first decade for which the required data are available. Taking the usual definition of skilled workers—craftsmen, foremen, and kindred workers—Table 8-3 reveals a higher proportion of skilled workers among the immigrants, 26.7 percent, than

|

22 |

Because the populations of the primarily European origin countries were more heavily agricultural than the American population and because by most accounts the agricultural labor force in Europe ("peasants") were the least skilled and least educated of European workers, these data provide further support to the conclusion stated above that the immigrants tended to come from the higher strata of European society. |

TABLE 8-3 Occupational Distribution of Nonagricultural Workers in the U.S. Work Force in 1910 and Occupations Reported by Immigrants Upon Their Arrival During the Decade 1900–1910

|

Occupation Classification |

U.S. Work Force |

Immigrants |

|

Skilled |

16.8 |

26.7 |

|

Unskilled |

39.3 |

46.0 |

|

Domestic Service |

14.1 |

6.7 |

|

Professional |

6.8 |

2.0 |

|

All Other |

23.0 |

18.6 |

|

NOTE: For the U.S. labor force the occupational classification for skilled corresponds to "craftsmen, foremen and kindred workers," unskilled are "operative and kindred workers and laborers except farm and mine" domestic service include "private household workers and [other] service workers," and professional include ''professional, technical, and kindred workers." SOURCES: U.S. Workforce: David L. Kaplan and M. Claire Casey. Occupational Trends in the United States, 1900–1950. U.S. Bureau of the Census Working Paper No. 5. Washington: U.S.Government Printing Office, 1958. As reported in United States Bureauof the Census. Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970,Bicentennial Edition. Two volumes. Washington: U.S. Government PrintingOffice, 1975. Electronic edition edited by Susan B. Carter, ScottS. Gartner, Michael R. Haines, Alan L. Olmstead, Richard Sutch, andGavin Wright. [machine-readable data file]. New York: Cambridge UniversityPress, 1997, Series D182–198. Occupations of arriving immigrants: Ernest Rubin. "Immigration and the Economic Growth of the U.S.:1790–1914." Conference on Income and Wealth. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1957: 8. As reportedin Elizabeth W. Gilboy and Edgar M. Hoover. "Population and Immigration."In Seymour E. Harris, ed., American Economic History. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961, table 7: 269. An obvious error inDomestic Services has been corrected. |

||

among the resident American labor force, 16.8 percent. Table 8-3 also reveals a relatively lower proportion of domestic servants among arriving immigrants.

Yet as we have noted, at the same time, immigrants were relatively more likely to report "unskilled" occupations than were American workers, which complicates the interpretation of the data. Moreover, and not surprisingly given the young ages of immigrants, professionals were also not well represented among the new arrivals. In an effort to help clarify the picture, we have grouped the skilled, the professional, and "all other" occupations into a single category and contrast the share of these relatively high-status occupations with the share of the unskilled and domestic service occupations. This exercise reveals that 47.3 percent of the nonagricultural immigrants reported relatively high-status occupations while 52.7 percent were unskilled or in domestic service. In this sense, immigrants were (slightly) more likely to be unskilled than skilled. Yet this distribution is nearly exactly the split within the resident American nonagricultural labor force: 46.6 percent in relatively high-status occupations and 53.4 percent in either unskilled or domestic service occupations. We might even say that the newly arriving immigrant nonagricultural work force in this decade was (slightly) more skilled than the resident American labor force.

The data on the occupations of arriving immigrants, shown in Table 8-1,

reveal very little in the way of a trend over time. The high-status occupations accounted for a stable 40 percent of immigrants reporting nonagricultural occupations between 1860 and 1900 and then rose to 47 percent in the final decade before World War I. This evidence contradicts the frequently made claim—put forth without evidence—that the skills of immigrants were falling in this period.

Of course, there is good reason to be cautious about data on immigrant skills. The occupations were self-reported and recorded by ship captains who may have imposed prejudices of their own. Presumably the new arrivals reported the occupation they had followed in the old country, but perhaps young immigrants reported their father's occupation or perhaps some reported their intended occupation in America. In any case, there is strong evidence that many of the new arrivals took jobs other than those they reported on entry. Farming, in particular, was difficult to enter because of the cost of purchasing and equipping a farm and the evident fact that a year's worth of provisions or credit would be required before the first crops came in. Differences in technologies, the quality of the final product, and the organization of trades may have reduced the value of European-acquired skills (Eichengreen and Gemery, 1986). For this reason many researchers have examined, not the occupations immigrants reported on arrival, but the occupations actually taken up by immigrants in their new home.23

Occupations of the Foreign Born in the United States

The federal census provides data on the occupations of the labor force by the nativity of the worker. Hill (1975) categorized these occupations as either "skilled," "semiskilled," or "unskilled,'' using the classification devised by Edwards (1943). The results of this exercise led Hill to conclude that "the native and foreign born were of relatively comparable economic status" during the period of mass immigration (Hill, 1975:59). Although the foreign born were slightly less likely to have been employed in skilled positions and slightly more likely to have been employed in unskilled positions, they were much more likely to have held semiskilled jobs. Their share of the semiskilled jobs is disproportionately large enough to bring them close to occupational parity with the native

|

23 |

Occupations actually taken up by immigrants will not adequately indicate their skills either if immigrants face discrimination in their entry into occupations. A number of scholars have argued that immigrants did in fact face occupation-based discrimination during the era of mass migration (Azuma, 1994; Barth, 1964; Brown and Philips, 1986; Cloud and Galenson, 1987; Daniels, 1962; Hannon, 1982a, 1982b; Higgs, 1978; LaCroix and Fishback, 1989; Liu, 1988; Murayama, 1984; and Saxton, 1971). But see Chiswick (1978a, 1978b, 1991a, 1991b, 1992, 1994) for an analysis that emphasizes the role of human capital in immigrant occupational attainment. The consensus in the literature is that within occupations immigrants were paid roughly equal pay for equal work (Blau, 1980; Ginger, 1954; Higgs, 1971a; McGouldrick and Tannen, 1977). |

born despite their disadvantage at the upper and lower ends of the occupational spectrum.24

WAS IMMIGRATION GOOD FOR GROWTH?

Mass immigration occurred during a period of very rapid economic growth and America's ascendancy to international industrial leadership (Wright, 1990; Abramovitz, 1993). Most of the historians and economic historians who have studied immigration have tried to assess its relationship to these positive economic developments. To do so they relied, explicitly or implicitly, on a model of economic growth and of factor mobility. For those unfamiliar with this literature, it will be helpful to begin with some key definitions and a simple version of the model.

Defining Growth

There is little doubt that immigration caused the American population and the American labor force to grow more rapidly than it would have in its absence.25 Figure 8-14 shows the contribution of net immigration to American population growth. During the period of mass immigration preceding World War I, immigration accounted for somewhere between a third and a half of U.S. population growth.26

More workers meant more output. Population, after all, is fundamental to production, not only because people supply the labor required, but because the consumption of the population is the raison d'& ecirc;tre of the production system. Thus the size of the economy, measured, say, by real gross domestic product (GDP), grew more rapidly than it would have without immigration. This is, we think,

|

24 |

The semiskilled class is largely made up of factory operatives, a class of occupations that is classified as "unskilled" in Table 8-1. |

|

25 |

Because net immigration was positive throughout the entire history of the country before World War I, this would be a tautology except for the possibility that the flow of immigrants somehow might have induced a decline in the natural rate of increase of the native-born population sufficiently large to numerically cancel the inflow. This possibility was actually suggested by Walker (1891, 1896). Although it is true that both the fertility rate and the rate of net population growth from natural increase fell over the nineteenth and first third of the twentieth centuries, most demographic studies of population dynamics lend little or no support to the Walker hypothesis. We summarize this literature in the section of this chapter on population dynamics. |

|

26 |

It is interesting to note that net immigration also accounts for about a third of the growth in the U.S. population today. This is true despite the fact that the numbers of arriving immigrants are smaller and the base population is larger today than it was in the decades immediately preceding World War I. The reason for the relatively large contribution of immigration to American population growth today is that the rate of natural increase is so low. Data on net immigration come from McClelland and Zechhauser (1983) for 1820–1860, Kuznets and Rubin (1954) for 1870–1940, and the Bureau of the Census (1990, 1993) for the recent period. |

FIGURE 8-14 Net immigration's contribution to national population growth.

what historian Maldwyn Allen Jones had in mind when he wrote in his classic book, American Immigration:

The realization of America's vast economic potential has … been due in significant measure to the efforts of immigrants. They supplied much of the labor and technical skill needed to tap the underdeveloped resources of a virgin continent. This was most obviously true during the colonial period. … But immigrants were just as indispensable in the nineteenth century, when they contributed to the rapid settlement of the West and the transformation of the United States into a leading industrial power (Jones, 1992/1960:309–310).

But this concept of growth, sometimes called "extensive growth," is not what economists usually mean by the phrase "economic growth." Instead, the growth of labor productivity, or the growth of per capita output, or the growth in the standard of living—''intensive growth" —is usually of greater interest. Labor productivity for the economy as a whole is measured by dividing GDP by the number of workers. Thus, if productivity is to grow, GDP must grow faster than the employed labor force. If per capita output is to grow, GDP must grow faster than the population. so the question becomes: Does immigration increase or reduce labor productivity? If workers are paid a wage that reflects their productivity, we can ask the same question as: Does immigration increase or reduce the real wage?27

|

27 |

There are other influences on the real wage than productivity. Of particular importance in this context would be discrimination (presumably against immigrants and in favor of native-born workers) and unionization (presumably weakened by heavy immigration). |

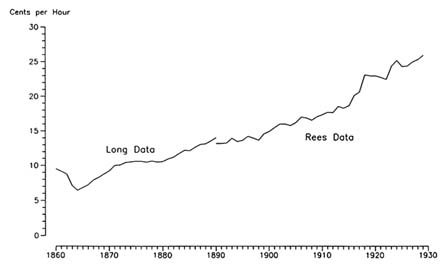

The statistical record is clear: Intensive economic growth did take place during the era of mass immigration. Per capita GDP grew in real terms (Balke and Gordon, 1986), so did labor productivity. Real wages rose (Long, 1960; Rees, 1960). Nonetheless, this evidence is not adequate to rule out a harmful role for immigration. During the late nineteenth century, and, indeed for most of U.S. history, output per worker was growing.28 Thus, the real question is whether immigration retarded or accelerated the rate of intensive growth.

At first glance it would appear that there is no clear consensus among economic historians about the impact of turn-of-the-century immigration on the rate of intensive growth. The most careful of the several reviews of the historical literature, that by Atack and Passell (1994:236–237), concludes that there was a large, positive, and "profound" effect of immigration on the rate of growth measured in per capita terms. On the other hand, Williamson asserts without qualification that

The issue in American historiography, however, has never been whether immigration tended to suppress the rise in the real wage. … Surely, in the absence of mass migrations, the real wage would have risen faster … (Williamson,1982:254).

Hatton and Williamson test this proposition in their recent book, The Age of Mass Migration: An Economic Analysis.29 They conclude that late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century immigration "significantly retarded the growth of real wages and living standards economy-wide" (Hatton and Williamson, 1998:Chap. 8).

It seems to us that there are three factors that underlie the apparent divergence of opinion about the impact of immigration: definitions of the population of interest, composition effects, and model specification.

Defining the Population of Interest

Which is the population for whom the effects of immigration are to be measured? Is it the entire population, including the newly arrived immigrants? Is it the population resident in the United States at the time of the immigrants'

|

28 |

Annual additions to per capita output averaged 1.7 percent per year in the early era of mass immigration between 1901 and 1913 (two business-cycle peaks). (This calculation is based on figures reported in Bureau of the Census (1975/1997, F4). This sustained growth meant that over that 12-year period, average per capita income increased nearly 25 percent. This calculation includes the newly arrived immigrants in the base population. Changes in the standard of living over a lifetime are very sensitive to small changes in the annual rate of growth. For example, with an annual rate of growth of only 1 percent, output increases 63 percent over a 50-year period. With a 2 percent growth rate the improvement is 164 percent, and with a 5 percent growth rate (much slower, by the way, than the rate of growth of per capita output in China today) the standard of living increases 100-fold. |

|

29 |

This book is scheduled to be published in 1998. Hatton and Williamson graciously provided us with a manuscript copy at the time we were writing this chapter. |

arrival? Perhaps it is the native born, or even the native born of native parentage. Are workers alone to be considered, or the workers and their dependents? Just workers and their families, or capitalists and landowners as well? Any of these populations may be a legitimate focus of attention. The appropriate definition depends on the question being asked. One source of confusion in the literature stems from the fact that scholars have not always been explicit about the definition they have chosen.30

Composition Effects

To measure the impact of immigration on the wages of natives and of past immigrants, one needs to partition the population between the resident population and the new immigrants and consider changes in the welfare of the resident population alone. For the most part, however, long-term historical data on wages, income, and wealth are available only for the population as a whole. Scholars are forced to deduce the impact of immigration on the welfare of the resident population (or the native born or the native born of native parents) from data on the entire population.

Such a project is, of course, fraught with hazards. An aggregate time series on wage rates (or living standards) may rise slowly or even fall at the same time that the wages of both the resident population and the newly arrived immigrants are rising rapidly. This would occur if, say, the newly arrived immigrant share of the population were rising rapidly and the wages of the newly arrived immigrants were below those of the resident workers.

Model Specification

To assess the impact of immigration on intensive economic growth, economic historians have implicitly or explicitly relied on a theoretical construct known as the "aggregate production function." This approach asserts that the aggregate output produced by an economy (its gross national product) is determined by the quantities and qualities of its "factors of production": capital, labor, and land. Technological progress plays a role too, either because better machines and tools are used ("embodied" technical change) or because existing machines and tools are organized in better ways ("disembodied'' technical change).

Capital includes machinery and buildings and other structures—all of the

|

30 |

Thus, it becomes clear only after a careful reading that Lebergott (1964:163) is interested in the impact of immigration on the wage rates of the entire population of workers, including the wages of the newly arrived immigrants. Hatton and Williamson (1998:Chap. 8), however, cite Lebergott in support of their contention that immigration slowed the growth rate of wages of natives and of past immigrants in the early decades of this century. |

manufactured physical inputs into the production process that contribute to the level of output. Labor includes number of persons involved in the production process, their hours of work per day, their days of work per year, the intensity of their work effort, and their level of skill. Land includes improvements to land, natural resources, and raw materials. A key feature of this theoretical construct is that it focuses attention on the productivity of factors of production and on the possibility of substitution among capital, labor, and land. Thus, for example, an increase in labor (perhaps from immigration) would be supposed to raise the productivity of capital and thus would create an incentive to invest and further expand the capital stock.

The aggregate production function approach is used to compare the historical record with an explicit counterfactual; a comparison between the historical record and an explicit counterfactual; a comparison of "what was" with "what might have been" had immigration flows been absent or reduced. To assess the impact of immigration on growth, the investigator must specify a general equilibrium model of both the labor and capital markets and of the production and distribution of output.31

The counterfactual method has a long history in cliometric work.32 By now it is clear that the outcome of such an exercise is quite sensitive to the specification of the formal theoretical model that describes the workings of the counterfactual universe. The aggregate production function must be specified mathematically and assigned numerical parameters. Is the production function Cobb-Douglas, or constant elasticity of substitution (CES), or Leontief? Are there economies of scale? Is the growth of the capital stock constrained by the flow of savings or by available investment opportunities? Is the model static or dynamic? The results also depend upon the assumptions built into the model about the distribution of wealth, income, and employment. Are workers paid their marginal product? Are governments redistributive? Do immigrants import or export capital? Do immigrants and native born have different savings propensities? Is the macro economy Keynesian or neoclassical? Because the conclusions reached through counterfactual modeling are so sensitive to the model's structure, the persuasiveness of any such exercise depends crucially upon the plausibility of the model specification.

Given this state of affairs, the most helpful thing we can do is to describe some of the prominent arguments about relevant aspects of the economy that appear in the literature. The reader will note that many of these issues are difficult to resolve with the available data and that the literature itself has given insufficient attention to the data that are available. In the absence of more

|

31 |

For an early and influential example of the counterfactual method that uses a computable general equilibrium model to examine the immigration question with late nineteenth-century data, see Williamson (1974a). Williamson concludes, "An America without immigrants indeed would have grown very differently from how she actually did in the late nineteenth century" (p. 387). |

|

32 |

For a discussion see Fogel (1967). |

empirical work, the conclusion readers reach will depend in large part on their tastes for various theoretical constructs. In the process of constructing our catalog, we reveal our own priors.

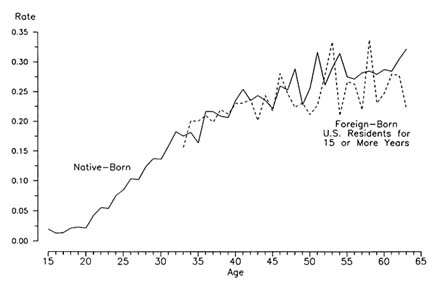

Labor Force Participation of Immigrants

Most economic historians noted that early twentieth-century immigration caused the labor force to grow more rapidly than the population (Kuznets, 1952:196–204). Immigrants in that period were disproportionately young males and more likely than their native-born counterparts to be labor force participants. Most economic historians place great weight on the fact that immigrants who arrived in the last era of mass migration were far more likely to participate in the labor force than the average American at the time. This pattern is shown in Table 8-4, which displays the share of the native- and foreign-born populations engaged in the work force for the decennial census years 1870 through 1940. The participation rate for the foreign born is 50 percent or more from 1880 onward, with the rate rising with the rising tide of immigration. The participation rate of the native born is only about two-thirds of this level. Kuznets explained the high labor force participation of immigrants in this way:

Because the immigrants were predominantly males, because by far the preponderant proportion of them (over 80 percent) were over 14 or 15 and in the prime working ages, and because their participation in the labor force tended to be higher than that of the native population even for the same age and sex classes,the share of foreign born among the gainfully occupied was, throughout the period,markedly greater than their share in total population (Kuznets, 1952,1971b).

we have already examined data demonstrating the predominance of males of young working ages in the turn-of-the-century immigrant streams. If these foreign-born workers were as productive as the native born and if their arrival did not depress the capital-labor ratio (that it did not is commonly supposed in the historical literature), then immigration would cause per capita income of the resident population to rise more rapidly than it would have in the absence of immigration (Gallman, 1977:30).33

The first element of the argument—that overall per capita incomes tend to rise because of the immigration-induced increase in the labor force participation rate— is well established. The balance of the argument—that immigration had at least a short-term positive impact on the economic well-being of the resident population— depends on two assumptions that are less well supported by empirical work. One

|

33 |

As already mentioned, in the short run the influx of new labor is likely to depress the capital-labor ratio before it is restored through new investment. If the capital stock is disproportionately owned by native-born residents, as was surely the case in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, then native-born owners of capital will benefit temporarily from higher returns to capital. Indeed, it is this higher return to capital that (in part) is thought to induce an increased volume of investment that ultimately restores the capital-labor ratio to its preimmigration level. |

TABLE 8-4 Labor Force Participation Rate, Native and Foreign-Born, 1870–1940

|

Year |

Native Born |

Foreign Born |

|

1870 |

29.7 |

48.5 |

|

1880 |

32.0 |

52.2 |

|

1890 |

33.1 |

55.1 |

|

1900 |

35.5 |

55.5 |

|

1910 |

37.7 |

57.8 |

|

1920 |

37.8 |

55.7 |

|

1930 |

38.1 |

52.2 |

|

1940 |

39.1 |

50.5 |

|

NOTE: "Labor force participation rate" is defined here as the share of the total population of a given nativity that is engaged in the workforce. SOURCE: Calculations are based on Kuznets (1971b). |

||

point has to do with the nativity differences in worker productivity (or immigrant "quality") discussed above. The consensus is that any differences in the average productivity of the native- and foreign-born work force were small. The second key point—the impact of immigration on capital formation—has been left largely to assumption and speculation. Very little empirical work with historical data has been reported in the literature. There are really two questions. One is, was the growth of capital constrained by saving (at a given interest rate) or was it constrained by the growth of investment opportunities? A second question is to what extent did immigrants either import physical capital or save heavily?

Immigration and the Capital-Labor Ratio

In the short run at least, an influx of immigrants who do not bring capital with them will have the effect of "diluting" the capital stock, that is, reducing the economy-wide capital-labor ratio. If capital and labor are substitutes, this reduction in the capital-labor ratio will raise the rate of return to capital and lower the real wage of workers. The overall impact of this dilution of capital on the initial resident population is predicted by theory to be positive. Capital owners—all of whom are posited to be native born—will gain and workers will lose, but the gains of the capital (and land) owners should exceed the losses of the resident laborers. This is because the labor and capital owned by residents can produce more output after the arrival of the immigrants than before. Immigrants will increase output by more than they will take home in wages.34

|

34 |

Denison (1962:177) suggests that immigrants will take home only 77.3 percent of the increase (labor's share in national income); the rest goes to the resident owners of capital and land. Other scholars estimate an even lower share for labor—closer to 60 percent (Abramovitz, 1993; Taylor and Williamson, 1997). |

In his discussion of the probable magnitudes of the redistribution affected by this mechanism in the modern era, Borjas estimates that immigration effects a loss to native workers of about 1.9 percent of GDP and a gain to native capital owners of approximately 2 percent of GDP. Borjas suggests that this relatively small net surplus, especially compared with the larger wealth transfers from labor to capital, "probably explains why the debate over immigration policy has usually focused on the potentially harmful labor market impacts rather than on the overall increase in native income" (Borjas, 1995:8–9).

When considering the relevance of this redistribution for the period of rapid immigration in the early part of this century, we note first that many of the resident workers were also capital owners.35 Lebergott (1964:512–513) estimates that, as late as 1900, about one-third of the labor force were at the same time owners of land and capital. They were self-employed farm owners and the owners and operators of small retail shops and manufacturing plants. Others were providers of professional and personal services (Carter and Sutch, 1996). Also we note that a substantial fraction of American household heads and workers owned their own homes. Haines and Goodman (1995) put the level at over one-third near the turn of the century. To the degree that the arrival of new immigrants increased the demand for housing, owners of the existing stock of housing would enjoy capital gains.36