9

Immigration and Crime in the United States

John Hagan and Alberto Palloni

INTRODUCTION

There is increasing concern about the presence of immigrants in the criminal justice system of the United States, especially about the number of legal and illegal immigrants in prisons. In this chapter we include estimates that from 4 to 7 percent of the more than 1.5 million persons held in American jails and prisons are noncitizens. At an average annual cost of more than $30,000 per inmate, the financial source of public and policy concern is obvious. This concern is increasing as state and federal governments become better informed about the immigrant status of offenders in their custody. The public and its politicians understandably are eager to find ways to reduce or shift this expense, while responding as well to concerns about public safety. One response involves efforts by states to shift expenses to the federal government by demanding compensation for the expense of incarcerating immigrants; another response is to press for the deportation of immigrants who are convicted of crimes; and a third response is to lobby for limitations on immigration and for stricter control of illegal immigration (see Cornelius et al., 1994). Our purpose in this chapter is not to assess directly the wisdom of these various policies, but instead to provide information and perspective on the relationship between immigration and crime. This information is relevant but not determinative with regard to selecting among the various policy options that arise from linkages between immigration and crime.

The United States has experienced at least four major waves of immigration over the past two centuries. Concerns about crime have been salient in conjunction with the two most recent waves, which occurred at the turn of this century and again

toward this century's end. We focus on issues of immigration and crime during these third and fourth waves. These periods are sufficiently different and far apart in time that it is necessary to relearn and rethink much of what was once taken for granted about this topic. This task is made more difficult by the fact that, in between the last two periods of concern about immigration and crime, many criminal justice agencies stopped recording information about the presumed immigration and citizenship status of offenders. It is therefore necessary to piece together information about our topic from a patchwork of sources. As we note, the depth and detail of the data sources we must draw from are uneven and uncertain. The results of our work suggest that some of the public concern about immigration and crime may be overdrawn; however, the nature of the data problems also limits the certainty with which conclusions can be drawn in this field.

Undoubtedly the most salient questions involve the issue of whether immigration increases crime. Of course, in an absolute sense, it probably does. Immigration brings more people into the country, and unless this process is counterbalanced by emigration, the absolute volume of crime will very likely increase. In addition, immigrants are often disproportionately male and at early ages of labor market entry and advancement. Because young males are disproportionately likely to be involved in crime in all parts of the world that we know about (Hirschi and Gottfredson, 1983), this may also contribute to increases in crime. If our concern is solely to reduce crime, it simply does not make sense to encourage young males to immigrate in large numbers. However, because we also value the labor of young male immigrants, and indeed often rely on this labor in the context of shortages of particular kinds of workers, questions about contributions of immigration to crime are more likely to be relative than absolute. In this sense we will probably want to know whether immigrants who enter the country contribute to crime beyond what we could otherwise expect of citizens of similar numbers, ages, gender, and so on.

A further complication in assessing the involvement of immigrants in crime is that immigrants may not be treated the same as citizens in the criminal justice system. If immigrants are more or less vulnerable than citizens to arrest, detention, conviction, and imprisonment, their representation in official crime statistics may be correspondingly biased. This problem as well must be addressed in assessing the relationship between immigration and crime. These difficulties help to explain why questions about immigration and crime have recurred over the past century in the United States. We first review the historical background of these concerns and then turn to contemporary developments in reaching tentative conclusions about immigration and crime.

IMMIGRATION AND CRIME IN AN EARLIER ERA

The close of the Past century brought concerns about immigration and crime that persisted for several decades. These concerns were associated with a third

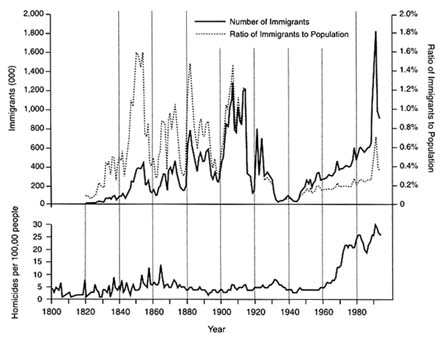

wave of immigration depicted in Figure 9-1; the persistence of these concerns ultimately helped to justify a closing off of this wave of immigration. A bill passed by Congress in 1891 barred immigrant carriers of contagious diseases and "immoral" people. Later, public perceptions of immigrant alcohol use and public drunkenness in association with fears of crime facilitated the passage of Prohibition. Congressional acts in 1921 and 1924 substantially reduced the numbers of immigrants admitted to the United States. Special attention was directed toward southern and eastern Europeans during this time, although statistical analyses usually compared native-born whites with the foreign born more generally.

Aside from highly questionable writings associated with the eugenics movement, the research of this earlier era provided little evidence of a causal association between immigration and crime. Homicide rates from this period in New York City, presented in Figure 9-1, reveal no systematic relationship, and McCord's (1995) assessment of the research literature from this period indicates that immigrants were not, as was often alleged, particularly prone to drunkenness or crime (Abbott, 1915; Powell, 1966; Taft, 1936; van Vechten, 1941; compare

FIGURE 9-1 Number and ratio of immigrants to population in the United States, 1820–1993 and New York City homicide rates, 1800–1993. Source: Isbister (1996:34) and Butterfield (1994).

with O'Kane, 1992). Although McCord noted that immigrants accounted for a disproportionate amount of crime in Boston in 1914, in Chicago native-born residents were more likely to be criminal (Gault, 1932). Meanwhile, increasing immigration did not bring higher crime rates to Philadelphia (Hobbs, 1943), and homicide rates in this city were lower among almost all foreign-born groups than among the native born (Lane, 1979).

Where causality was seen to operate, its direction often was in the opposite direction expected. A report by the United States Immigration Commission found higher crime rates among the children of native-born parents and among children of immigrants than among immigrants themselves (Park et al., 1925/1967). Such findings provided early support for the view that it was the acculturation of immigrants into American life that most notably increased their likelihood of involvement in crime.

In the first part of this century prominent criminologists, such as Edwin Sutherland and Thorsten Sellin, wrote extensively about immigration and crime (see Hawkins, 1995). Sutherland and Sellin were critical of both the data and commentary of this early period, especially when it purported to show higher rates of crime among foreign-born immigrants than among the native-born (see United States Immigration Commission, 1911; National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement, 1931). In several early editions of the most influential textbook on crime of this century, Sutherland (1924, 1934) advanced the view that acculturation rather than immigration was associated with crime. He reported evidence that second-generation immigrants had higher rates of crime than first-generation immigrants, and that immigrants to America had higher rates of serious crime than their counterparts in their native countries (citing Taft, 1933). Sutherland (1934) and Sellin (1938) both noted that immigrants who came to America as children were imprisoned at a higher rate than immigrants who came as adults.

Sutherland and Sellin further argued that official crime statistics were dubious resources for reaching conclusions about immigration and crime. Sutherland (1924) observed that comparisons of crime among the foreign and native born were not meaningful unless differences in ages, rural-urban, and sex distributions were taken into account. Sellin (1938) added that the official data sources were often crude and mistaken in their attributions of national origins to assumed offenders. Researchers were increasingly concerned about ethnic and racial biases that resulted from the discretion involved in policing and prosecution of crime (see Brown and Warner, 1995).

Still, Sutherland and others reserved room in their thinking for the possibility that in some circumstances some national groups might bring increased risks for particular kinds of crime. Similarly, they noted that no single nationality grouping displayed the same level of involvement across all types of crime. Sutherland and Cressey (1978:149) reasoned as late as the 1978 edition of their text that

certain crimes or groups of crimes are characteristic of certain national groups. These same types of crime are, usually, characteristic of the home countries also. The Italian and Turkish immigrants residing in Germany in 1965 had high rates of conviction for murder and assault: Italy and Turkey also have high murder and assault rates. Italians in America have a low rate of arrest for drunkenness, and drunkenness is comparatively rare in Italy. The traditions of the home country are transplanted to the host country and determine the relative positions of the immigrant groups to the types of crime.

In apparent contrast with this view, Shaw and McKay (1942:152–154) argued that, although immigrants came to North America with differing national propensities to crime, the disorganizing forces of poverty in the centers of American cities where immigrants most often settled tended to produce a convergence in their involvements in crime. So that where, ''… the older immigrant nationalities as well as the recent arrivals range in their rates of delinquency from the very highest to the lowest," nonetheless, "within the same type of social area, the foreign-born and the natives, recent immigrant nationalities, and older immigrants produce very similar rates of delinquency." These contrasting views emerging out of the early twentieth century American experience with immigration and crime are not necessarily contradictory, a point we return to later.

Meanwhile, during the middle third of this century concern about immigration and crime declined and nearly disappeared. A reflection of this is that the lengthy discussion of immigration and crime that had been an important part of the earlier versions of Sutherland's classic text was eliminated completely between the tenth and eleventh editions. Official statistics on crime no longer regularly included reports of the foreign nationalities of offenders. With the exception of occasional panics about Italian-American involvement in organized crime (Cressey, 1969) and scholarly speculation about the successive involvement of the Irish, Jews, and Italians in organized crime (Ianni, 1972; see also O'Kane, 1992), fears about immigration and crime gradually faded into the background of public and criminological concerns. Earlier waves of European immigrants assimilated into American society and became citizens, while immigration and crime both declined through the 1950s, and public fears subsided.

IMMIGRATION AND CRIME IN A NEW ERA

As a fourth wave of immigration emerged in the last third of this century, earlier concerns took on renewed life. As indicated in Figure 9-1, the increase in immigration during this latter period was more notable in absolute volume than in relation to population. Nonetheless, the renewed fear was that "under current immigration laws and procedures, frighteningly large numbers of newcomers see crime as their avenue to the American dream" (Tanton and Lutton, 1993:217). The new circumstances were, however, somewhat different than those at the beginning of the century. Whereas concerns linking immigration to crime in the

first half of this century coincided with historically low crime rates, from the later 1960s until relatively recently, violent crime increased in the United States. So that while between 1960 and 1990 the annual migration rate per 1,000 population in the United States increased from 1.7 to 3.0, during this same period the U.S. homicide rate increased from 4.8 to 8.3 per 100,000 population. This recent increase in homicide, and even more recent decline, is further reflected in the homicide rates for New York City displayed in the bottom panel in Figure 9-1.

With the data available to us we were able to trace time trends in the rate of arrests, rates of incarceration, and rates of immigration. Estimated rates of immigration were obtained by adding together figures for legal immigrants and estimated illegal immigrants. The latter were determined by distributing over time estimated numbers of individuals who entered the country between 1975 and 1990.

Our preliminary analyses indicated that trends in arrest rates and immigration rates were only weakly if at all related; however, there was a modest association between the latter and trends in the arrest rates. This association is attributable mostly to a sharp upturn in both trends that occurred particularly after 1985. So increases in violent and other forms of crime may be mixed in the perceptions of the American public with the renewed growth in immigration.

As was the case at the turn of the century, concerns at this century's end are prominently focused around the presence of inmates in American prisons who are not citizens. Indeed, the most comprehensive national statistics we now have on immigration and crime come from prison and correctional department data. Most police and court agencies do not systematically collect information on the citizenship and national origins of persons arrested and prosecuted, probably because it is now better recognized that the attributions involved would often be mistaken. Unfortunately, the pictures provided by prison statistics may also be distorted, not only by mistaken attributions of citizenship and national origin, but also because only a small proportion of criminal offenders ultimately are incarcerated and because bias may be introduced by the long sievelike process that leads to incarceration. This sievelike progression includes selection processes that result in both the exclusion and the inclusion of immigrants from the ultimate risk of incarceration. For example, although it is the case that police are often assumed to concentrate attention on immigrants along with other minorities, it is also the case that immigrants are sometimes simply deported rather than charged with crimes. Research is needed to establish whether these early sources of selection in the criminal justice system simply counterbalance one another or lead to systematic over- or under representation of immigrants in prison.

Meanwhile, even our knowledge of prisoners is limited by the absence of comprehensive national data. Our knowledge of incarcerated offenders is based largely on a survey of state prison inmates conducted in 1991 (U.S. Department of Justice, 1993) and on a survey of state and federal departments of corrections conducted in 1995 (Wunder, 1995). The former study is documented in greater

detail, with a reported response rate by surveyed inmates of about 94 percent, but is susceptible to the failings of the subjects' self-reporting, including problems of memory and deceit. The latter survey of correctional agencies reached high levels of coverage on some matters, but encountered bureaucratic problems on others, as illustrated by the California Department of Corrections, the largest prison system in the United States, which reported national origins of "immigrants" based on data collected on citizens as well as noncitizens. We are as careful as possible in this chapter to use the term immigrant only to refer to noncitizens and to use the term noncitizen instead of immigrant when the original sources do so; but there may be some cases in which the original sources we rely on have included foreign-born citizens among immigrants without indicating they are doing so.

By 1980 the percentage of the U.S. population formed by noncitizens was estimated to be between 4 and 5 percent (see Isbister, 1996:37). The Survey of State Prisons reported that more than 4 percent, or 31,300 state prison inmates, were not U.S. citizens. The Department of Corrections survey indicated that more than 7 percent, or 71,294 state and federal prison inmates, were not U.S. citizens. The latter figure is larger in part because it includes federal prisoners and also because the survey was conducted two years later during a growth spurt in prison populations. However, there is still a disparity between these two sources that underscores the difficulties of assembling information on immigration and crime in the United States. This point is further underscored by a recent Bureau of Justice Statistics report (Scalia, 1996) that indicates that there were less than 19,000 noncitizens in federal prisons in 1994, more than 7,000 fewer noncitizens than indicated in the Corrections Compendium report from one year earlier referenced above (Wunder, 1995). Scalia's report indicates in its first figure (1996:1) that about 14,000 noncitizens were serving a sentence of imprisonment in a federal prison in 1991, whereas the last table in this report (1996:10) indicates that 9,916 noncitizens were inmates in federal prisons in 1991.

We are left with a range of estimates that between 4 and 7 percent of prison inmates in the United States are noncitizens, compared with estimates that legal immigrants constitute between 4 and 5 percent of the U.S. population, with perhaps as much as 1 percent more of the U.S. population being illegal immigrants (Passel and Woodrow, 1984). Of course, this tells us nothing about whether specific immigrant groups are over- or underrepresented in prisons. The most systematic and comprehensive published data on the national origins of noncitizens in prisons are found in the 1991 Survey of State Prisons. Nearly half of the immigrants in state prisons (47%) came from Mexico, whereas nearly another fourth (26%) were from Latin and Caribbean countries. Together, these figures indicate that a large majority of immigrant inmates in U.S. state prisons, perhaps between 70 and 80 percent, are of Hispanic origin. This distribution of the national origins of immigrants in state prisons is quite similar to that found among immigrants convicted of an offense in the U.S. district courts in 1994 (see

Scalia, 1996:Table 2). About 45 percent of the legal immigrants to the United States are Hispanic in origin (Heer, 1996:Table 5.4). Of course this grouping is itself quite heterogeneous, including immigrants from Mexico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, and other countries in Central and South America and the Caribbean islands.

The heterogeneity of immigrant groups is an important source of complication in the relationship between immigration and crime. Not only is there social and cultural variation, for example, among Hispanic immigrants, there may be further significant variation in self-selection to participate in particular kinds of crime, as well as in legal documentation, with regard to vulnerability to statutory mandatory sentences and further group-linked variations in age and gender. Of course, such sources of variation also plague studies of other general correlates of crime, such as poverty and family breakdown, and crime itself is a heterogeneous entity. These problems do not stop research on these topics, but they do constitute reasons for caution in reaching policy-related conclusions. We attempt to address some of these concerns below.

Calculated on the basis of the Survey of State Prisons, the imprisonment rate for U.S. citizens is about 3.5 per 1,000 population. This rate is used as the base for calculating ratios presented in the first column of Table 9-1 for the most frequently imprisoned immigrant groups in U.S. state prisons. These figures indicate that immigrants from Cuba and the Dominican Republic are incarcerated at rates between four and five times those of citizens, that immigrants from Mexico, Jamaica and Colombia are incarcerated at rates from two to two and one-a half times those of citizens, and that immigrants from Guatemala and El Salva-

TABLE 9-1 Rates of Incarceration in U.S. State Prisons Per 1,000 Population

|

Number of Persons who entered U.S. between 1980 and 1990 (in thousands) |

Inmates in State Prisons |

State Imprisonment Rate |

State Imprisonment Rate for Males 15–34*** |

|

|

National Origin |

||||

|

Mexico |

2,145 |

14,711 |

6.858 |

47.61 |

|

Cuba |

188 |

3,130 |

16.649 |

131.78 |

|

United Kingdom |

154 |

313 |

2.032 |

19.34 |

|

Vietnam |

336 |

313 |

1.073 |

6.81 |

|

El Salvador |

350 |

1,252 |

3.577 |

26.48 |

|

Dominican Republic |

185 |

2,817 |

15.227 |

126.98 |

|

Jamaica |

155 |

1,252 |

8.077 |

69.52 |

|

Colombia |

146 |

1,252 |

8.575 |

78.242 |

|

Guatemala |

154 |

626 |

4.065 |

73.33 |

|

State Citizens |

217,182* |

751,200** |

3.459 |

45.51 |

|

*U.S. Population less foreign-born noncitizens **Inmates who are U.S. citizens ***Rate based on adjusting base for country-specific immigrant sex ratio and overall immigrant age distribution |

||||

dor are incarcerated at about the same rate as citizens. Recall that the circumstances of immigration from Cuba and the Dominican Republic have been shaped quite uniquely by political forces that have led many individuals with backgrounds in crime to migrate to the United States: for example, when Castro allowed over 100,000 people, including many prison inmates, to leave Cuba in 1980. A result is that there is considerable variability in Hispanic rates of imprisonment, and it is therefore a mistake to assume that these rates are uniformly high or that there is an undifferentiated relationship between immigration and crime.

Rates of immigrant imprisonment are complicated further by the fact, noted at the outset of this chapter, that immigrants are younger and more often male than are citizens. Because young men are at much greater risk than others for involvement in crime and imprisonment, the base used in calculating an imprisonment rate for immigrants is probably most usefully adjusted for sex and age. In the last column of Table 9-1 we have calculated imprisonment ratios using denominators for the compared rates that estimate the male populations of immigrants between 15 and 34 years of age from the various countries. The resulting ratios reveal a greater similarity between immigrants and citizens than was previously apparent.

The adjusted male rate for Mexican immigrants between ages 15 and 34 (47.61) is particularly notable because it is quite similar to the U.S. citizen rate (45.51). By this measure, the image of Mexican immigrants as more criminal than citizens is somewhat misleading. The imprisonment rates for some of the remaining countries are still substantially higher than the citizen rate. The Jamaican (69.52), Guatemalan (73.33), and Colombian (78.24) rates cluster at an intermediate level, whereas the Dominican (126.98) and Cuban (131.78) rates cluster at a higher level. However, even the latter rates are now less than three times, whereas they were previously more than four times, the citizen rate. It is important to keep in mind that, although the Cuban and Dominican rates are relatively high, in absolute terms these are rather small immigrant population groups, and therefore their contributions to prison populations are limited. Mexicans (14,711) form by a multiple of more than four (compared with 3,130 Cubans) the largest group of state prison inmates, even though their age-adjusted male state imprisonment rate is similar to that for citizens. This brings us back to a point made above, that if crime reduction is the sole and absolute priority, there is reason for concern.

However, there is also the further consideration that imprisonment rates inevitably are a result of several factors: involvement and apprehension for criminal behavior and decisions made about the prosecution and punishment of this behavior. As we further document below, there is reason to believe that Mexican and other immigrants may experience some unique risks of imprisonment for their crimes. These risks may result from differences in initial and predisposition custody decisions for illegal aliens. Detention prior to trial and sentencing is commonly found to increase the likelihood of conviction and ultimate incarcera-

tion (see Hagan and Bumiller, 1983). It may also be the case that immigrant drug offenders are sentenced with greater severity than others.

The most detailed recent study of criminal justice processing decisions involving immigrants was undertaken in El Paso and San Diego by Pennell et al. (1989). This study found in both cities that illegal aliens made up the largest proportion of immigrants prosecuted, and that these illegal aliens were much less likely than others to be released from jail prior to trial. For example, in El Paso only 14 percent of illegal immigrants compared with over 50 percent of all others were able to "bailout" prior to trial. This difference may be associated with the fact that the Immigration and Naturalization Service can place "holds" on illegal immigrants, that illegal aliens are financially less able to post bail, and that illegal immigrants are less likely to have the community ties that often are required for early release. When accused persons are unable to obtain release they may have greater difficulty generating resources to defend themselves in court, leaving them more vulnerable to conviction, and ultimately to imprisonment.

To assess the above possibilities we reanalyzed the Pennell et al. data that were collected in El Paso and San Diego. The results are presented in Table 9-2. These results confirm that immigrants in general in El Paso and San Diego are more likely to be detained prior to trial, and that, in turn, detention before trial increases the risks of conviction and imprisonment. That is, immigrants are at greater risk of conviction and imprisonment because they are more vulnerable to pretrial detention. In addition, immigrants in El Paso and San Diego who are charged with drug offenses are more likely than others to be sentenced to prison. These differences cannot be the result of immigrants having more extensive criminal histories, because Scalia (1996:Table 4) demonstrates that noncitizens are much less likely to have a prior known criminal history. A likely implication of these findings is that processing differences result in immigrants being overrepresented in prison populations. It will be important for further research to examine counterbalancing decisions, for example involving deportation, but the current findings suggest the likelihood that immigrants are overrepresented in prison as a result of justice system decision making.

An additional source of misperceptions about immigration and crime that may result from the uncritical reliance on prison statistics involves ways in which these figures are often used in characterizing immigrant criminality. The 1991 Survey of State Prison Inmates reported that nearly half of all alien inmates were incarcerated for drug offenses, that about 40 percent of these alien inmates used drugs during the month prior to their arrest, and that about 20 percent were under the influence of drugs at the time of their current offense. The 1991 survey reports that very high proportions of alien inmates from Colombia (87 percent) and the Dominican Republic (67 percent) were incarcerated for drug offenses.

Although it is the case that just over 20 percent of all inmates were incarcerated for drug offenses in 1991, about half of all inmates said they had been using

TABLE 9-2 Logit Models for Being Detained, Convicted, and Imprisoned in El Paso and San Diego

|

A. El Paso |

|||

|

Variables |

Pre-Trial Detention (n=2253) |

Conviction (n=2253) |

Incarceration (n=885) |

|

Immigrant |

1.35(.13)* |

-.08(.19) |

-.52(.40) |

|

Male |

.63(.19)* |

.48(.19)* |

.90(.39)* |

|

Less than 20 |

-.67(.11)* |

.34(.11)* |

-1.13(.19)* |

|

Violence |

-.49(.13)* |

-.68(.13)* |

.43(.25)+ |

|

Drugs |

-.70(.14)* |

.06(.14) |

.08(.24) |

|

Violence*Immigrant |

-1.10(.26)* |

-.09(.29) |

.36(.53) |

|

Drugs*Immigrant |

-.82(.39)* |

-.20(.30) |

1.17(.51)* |

|

Detained |

.44(.11)* |

1.74(.19)* |

|

|

Detained*Immigrant |

.33(.21) |

-.61(.42) |

|

|

Log Likelihood |

-1420 |

-1449 |

-506 |

|

B. San Diego |

|||

|

Pre-Trial Detention (n=2253) |

Conviction (n=2253) |

Incarceration (n=885) |

|

|

Immigrant |

1.26(.17)* |

-.59(.20)* |

-.16(.40) |

|

Male |

1.42(.37)* |

-.12(.21) |

-.16(.40) |

|

Less than 20 |

-.05(.17) |

.15(.18) |

-.32(.25) |

|

Violence |

-.17(.22) |

-.33(.21) |

.18(.70) |

|

Drugs |

-1.46(.37)* |

-.37(.22)+ |

-2.96(1.02)* |

|

Violence*Immigrant |

.05(.30) |

-.29(.38) |

.71(.41)+ |

|

Drugs*Immigrant |

-.07(.44) |

.57(.33)+ |

2.16(1.13)+ |

|

Detained |

2.29(.33)* |

2.29(.29)* |

|

|

Detained*Immigrant |

.79(.42)+ |

-1.15(.43)* |

|

|

Log Likelihood |

-730 |

-683 |

-372 |

|

* p8.05, two-tailed. + p8.10, two-tailed. |

|||

drugs in the month before their current offense, and more than 30 percent of all inmates said that they had been under the influence of drugs at the time of their current offense. So although there may be a concentration in drug offenses among imprisoned Hispanic offenders, especially from Colombia and the Dominican Republic, levels of drug use among Hispanic offenders in general seem to be about the same or lower than in the broader population of inmates. Scalia (1996:7) also reports that noncitizen offenders tend more often than citizens to be involved in "minor" and "low-level" drug offenses. This adds to the uncertainty as to whether and to what extent the imprisonment of Hispanic defendants from particular countries for drug offenses may be a product of their concentration in this type of crime as contrasted with the courts selecting this type of crime among immigrants from Colombia and the Dominican Republic.

There is further reason to question the impression left by prison statistics that Hispanic offenders are heavily involved with drugs. The research literature indicates that Hispanics compared with other Americans have lower rates of crack cocaine smoking (Wagner-Echeagary et al., 1994) and of drug-related deaths (Hayes-Bautista et al., 1994). These findings are part of a larger pattern indicating that recently arrived Hispanic immigrants are healthier on a variety of measures than other Americans, and that over time these differences diminish, with Hispanic Americans becoming more like other Americans in their health problems (Scribner, 1996).

Nonetheless, the perception remains that immigrants are a significant cause of American crime problems. The 1994 U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform set out to assess perceived and actual links between immigration policy and crime in El Paso. The Commission found that the El Paso crime rate was perceived as escalating dramatically in recent years in spite of efforts of local law enforcement agencies. This escalating crime problem was seen as resulting from El Paso's rapid urban growth, which in turn was fed by migration from Mexico, including a large illegal population. The Commission reported that "… many people believe that undocumented aliens are the source of the increase in serious crime in El Paso and that the increasing number of undocumented aliens is due to the U.S. Government's inability to control the border" (1994:18).

The Commission sought to assess the basis of these perceptions in several ways, including a comparison of El Paso with other cities of similar size and a regression analysis focusing on the effects of proximity to the Mexican border on crime rates in El Paso and elsewhere. The initial comparison with similarly sized cities was revealing. El Paso's total 1992 crime rate ranked 30th among 40 U.S. cities of comparable size. El Paso ranked above the mean for the 40 cities only on larceny-theft, for which it ranked 13th and was within 10 percent of the mean for all cities. This concentration in minor forms of property crime is consistent with the El Paso and San Diego study cited above (Pennell et al. 1989), which finds that about two-thirds of the illegal immigrants in each of these cities were arrested for property crimes, with only 9 to 15 percent arrested for drug crimes. Meanwhile, the 1994 Commission report indicates that the El Paso murder rate was little more than one-third of that for all the cities and was 12 percent lower than the national average. The murder rate for El Paso is also comparable to its border city Juarez. So in spite of its much higher rate of poverty, Juarez too has a relatively low homicide rate as least as compared with U.S. cities. Although, like other cities, El Paso saw increases in violent crime in the 1980s, it still remains at the lower end of the spectrum for cities of comparable size.

As a further means of assessing the possible effects of Hispanic immigration on crime, the Commission also reported the results of regression analyses on violent and property crime for 244 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) in the United States. In addition to including conventional measures of urban and economic conditions in these MSAs, the regression equations also included vari-

ables representing location within 100 miles of the U.S.-Mexican border or in Texas (if not on the border) or in another border state (Arizona, California, or New Mexico). The results of these regression analyses revealed that the border effects were all negative for violent crime and largely so for property crime. The conclusion from this analysis is that "if the data suggest anything about the border's impact on crime, it is that crime is lower on average in border areas than in other U.S. cities when the characteristics of the urban population are held constant" (1994:20). Nevertheless, the Commission concedes that a more direct test of the effects of immigration, especially illegal immigration, requires more specific measures.

We undertook a more direct test of immigration effects at the level of standard metropolitan statistical areas (SMSAs) by joining measures of legal and illegal immigration, developed by Bean et al. (1988) and based on a methodology used previously for the nation and states by Warren and Passel (1987), with Uniform Crime Report data collected by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The estimate of the legally resident noncitizen population was generated using alien registration data for 1980 from the Immigration and Naturalization Service and data on legally admitted aliens for January-March 1980 for SMSAs. This number was then subtracted from the figure for aliens counted in the 1980 census (corrected for nonreporting of country of birth, misreporting of citizenship, and misreporting of nativity) to obtain an estimate for undocumented aliens. Application of these procedures also yielded an estimate of legal noncitizens. The corrections and adjustments used in developing these estimates are described in greater detail by Warren and Passel (1987) and Passel and Woodrow (1984). Although these estimates of illegal immigrants are dependent on the numbers of undocumented immigrants included in the 1980 census, not the number actually present, Bean et al. (1988:39) indicate that "it is likely that the distribution … of the undocumented population not included in the 1980 Census might be similar to the distribution of those included."

We began our analysis with the 47 SMSAs considered by Bean et al. (1988) that are located in the five southwestern states of Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas, with four border SMSAs in Texas deleted because they include substantial areas and populations in Mexico. Thirteen of these SMSAs were not represented in the Uniform Crime Report data, so 34 SMSAs were ultimately available for our analysis. The three outcome measures of crime included violent crime rates, property crime rates, and total crime rates. Results are presented in Table 9-3.

We initially regressed logged arrest rates on the proportions of the population age 15 and over who were estimated in the 34 SMSAs to be illegal immigrants or noncitizens, black, and living in poverty. The illegal immigrant and noncitizen measures were introduced separately in equations to avoid collinearity problems. Box-Cox transformations were applied in this analysis and we selected the variant that produced the highest R2, which involved taking the logs of

TABLE 9-3 Linear Models of Crime Rates in Selected Southwestern SMSAs (n=34)a

|

Linear Models for Logged Arrest Rates |

|||

|

Total Variablesb |

Violence Arrests |

Property Arrests |

Arrests |

|

A. Illegal Immigrant Equations |

|||

|

Illegal Immigrants |

.07 |

.23 |

-.04 |

|

(.12) |

(.12) |

(.10) |

|

|

Black |

-.07 |

-.03 |

-.11 |

|

(.08) |

(.08) |

(.07) |

|

|

Poverty |

-.30 |

-.64 |

-.50 |

|

(.30) |

(.43) |

(.37) |

|

|

R2/L |

.03 |

.14 |

.10 |

|

B. Noncitizen Equations |

|||

|

Noncitizens |

.19(.14) |

.43(.12)* |

.12(.12) |

|

Black |

-.05(.08) |

.02(.07) |

-.10(.07) |

|

Poverty |

-.45(.45) |

-.92(.40)* |

-.59(.78) |

|

R2/L |

.08 |

.25 |

.12 |

|

a Standard errors in parentheses b Independent variables in linear models are proportions of population age 15 and above. * p 8 .05 |

|||

the independent and dependent variables. In no case was the measure of percent illegal immigrants significantly correlated with any of the three outcome crime measures, and the noncitizen measure was significant in only one case. As a further test of potential influence, we created dummy variables, with the SMSAs in the highest quartile on each variable coded as a dummy variable in poisson models of arrest counts. This operationalization was an attempt to capture the effects of more extreme concentrations of effected groups, with, for example, the dummy variable for proportion of illegal immigrants indicating SMSAs with more than 1 percent of the population in this group. This coding yielded more statistically significant but nonetheless inconsistent results, and so we do not present them. There is no consistent or compelling evidence at the SMSA level that immigration causes crime.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

We have suggested that an overreliance on prison statistics is a problematic basis for developing our understanding of immigration and crime. It is of further concern, in the political and economic context of cost reduction and shifting described at the outset of this chapter, that the prisons that collect these crime statistics may have an understandable interest in attracting atten-

tion to them, for purposes of offsetting high per inmate costs of incarceration. These statistics often are used to make the point that the numbers of immigrants in prison are substantial, and that a large proportion of immigrants who are in prison for drug charges are from Mexico. However, it is also the case that increasing numbers of immigrants have been coming to the United States from Mexico to work for employers who are eager to have them as employees (Calavita, 1994). These immigrants are disproportionately young and male, and therefore of an age and gender for whom crime is a relatively common and frequently transient experience, regardless of citizenship. So a first concern is to take into account not only the increased immigration that is occurring from Mexico, but also the age and sex distribution of these immigrants in considering their numbers in prison. When we do this we find that Mexican immigrants are found in state prisons at an adjusted rate that is not strikingly different from U.S. citizens. Of course, this does not mean we should be unconcerned about the growing numbers of Mexican immigrants in prison. The costs of this imprisonment are high and a concern with the absolute volume of crime involved is understandable. The adjustments for gender and age that we have introduced are intended to provide a context for understanding the numbers and costs involved.

At the same time, it is also important to take into account that immigrants from Mexico and elsewhere may be subject to differential treatment in the criminal justice system. For example, we have demonstrated that immigrants in El Paso and San Diego are at greater risk of being detained prior to trial, and that this results in their increased likelihood of being convicted and imprisoned. Also, we have shown that immigrants in these cities who are charged with drug offenses are at an elevated risk of being sentenced to prison. The overall implications of these findings will not be certain, however, until more is learned about potentially offsetting practices that result from diverting immigrants from the criminal justice system and deporting them from the country.

Another source of public concern is that immigrants, and especially illegal immigrants, are a source of drug problems in the United States. However, arrest records in cities such as El Paso and San Diego suggest that illegal immigrants are less likely than citizens to be involved in drug crime, and instead that they are most distinctively involved in property crime. This kind of petty property offense activity is consistent with the picture of offending that Freeman (1996) has suggested in his foraging model of crime. That is, young male illegal immigrants may be most likely to become involved in petty property crime as they attempt to satisfy basic subsistence needs while moving through the early stages of seeking, finding, losing, and regaining employment.

Overall, we did not find consistent evidence in macro- or micro-level data that immigrants are much more likely than citizens of similar ages and gender to be involved in crime. In particular, we have found that the image presented in prison statistics of the largest group of current immigrants to the United States,

from Mexico, is potentially misleading. Our data suggest that Mexican immigrants are more like their age and gender peers than is commonly assumed. This finding helps to resolve a paradox in the picture of Mexican immigration to the United States, because by other measures of health and well-being—including smoking, drug use, and the birthweight of babies—Mexican immigrants are generally found to do as well or better than U.S. citizens. One argument is that this is because of the strength of extended and nuclear families and religion in Mexican families. Insofar as this is the case, we may wish to place the priority on finding ways to preserve, protect, and promote the social and cultural capital that Mexican immigrants bring to their experience in the United States, rather than overemphasize issues of crime and punishment.

One especially important way in which Mexican and other immigrants to this country might benefit from better protection involves the risks to which they are exposed as victims of crime. In this chapter we have not considered the criminal victimization of immigrants largely because we could find no available source of data on this topic (but see Sorenson and Shen, 1996). The U.S. government invests large sums in public surveys of crime victimization, but these surveys do not include significant numbers of immigrants, and no special surveys of immigrants have been undertaken for this purpose. This task deserves special priority.

Also, and notwithstanding the potentially misleading picture we have found with regard to issues of immigration and crime, especially in the Mexican context, further work should be attentive to at least two poorly understood issues. The first involves the important task of making projections into the future that take into account interrelations among immigration, differential fertility, and social behavior. As we discuss in the Appendix to this chapter, higher rates of fertility among immigrant groups, either alone or in combination with other factors, such as criminal justice system bias, could result in immigrants forming larger proportions of prison populations in the future, even if their group propensities to crime remain constant. These processes are in need of further study.

Second, it is also likely the case that specific groups of immigrants, much like specific groups of citizens, do have a heightened propensity that leads them to be disproportionately involved in crime. This typically involves countries with relatively few immigrants to the United States. In these cases in which immigration is rather limited, there may be unique social networks and selection processes that explain the higher rates of crime involvement. If legal immigration from these countries was greater, it is plausible that rates of crime associated with these immigrant groups in the United States would be less striking, if only because the effects of these selection processes and social networks would be diluted. We know too little about these special cases to say much more, but enough to recognize that it is likely misleading to extrapolate from such cases to the experience of immigrants more generally.

APPENDIX: PROJECTIONS INTO THE FUTURE: INTERRELATIONS BETWEEN IMMIGRATION, DIFFERENTIAL FERTILITY, AND SOCIAL BEHAVIOR

A natural issue to address is the extent to which recent immigration trends will influence future trends of criminal behavior. The fact that we found little compelling evidence suggesting that those who enter the United States, either illegally or legally, have higher propensities to become involved in illegal activities does not necessarily imply that the relation will be absent in the future. The following are several hypotheses that deserve further consideration when data and resources become available.

Differential Fertility of Recent Immigrants Makes a Difference

Assume for the sake of simplicity that the immigration flow is stopped now and that those who have already gained entrance into the United States continue to behave as they have so far, that is, that their propensity to become involved in criminal activities remains constant and roughly the same as that of citizens. To the extent that current immigrants do indeed experience higher fertility than citizens—as some evidence seems to verify—the population exposed to become involved in crime 10–15 years from now will be disproportionately drawn from among recent immigrant groups. Several regularities will follow. First, the contribution of the immigrant population (also including the second generation) to the total crime rate will increase, as will their share among those who are incarcerated. This is not an effect of higher involvement in crime or of higher level of seriousness of offenses, but a simple result of the influence of differential fertility on the distribution of populations exposed to criminal activity. The larger than proportional contribution of immigrants to the population convicted and incarcerated will also persist if, as the data available to us seem to indicate, immigrants involved in crime are more likely to be convicted and incarcerated than comparable counterparts among citizens.

The relative contribution of immigrant groups will, of course, be higher if immigration trends continue and if their risk of becoming involved in criminal activities exceeds that of citizens. This is addressed below.

Success, Adaptation, and Increase in Criminal Behavior

As argued in the text of this chapter, a small subset of those who enter legally or illegally into the United States have higher propensities to commit crimes because their entrance into the United States is associated with ties to networks and organizations that employ them as cheap labor for organized criminal activities. The majority of immigrants, however, do not differ initially from other citizens of comparable socioeconomic status in their immediate involvement in

crime. Indeed, it can be argued that they may have even less propensity to become involved in criminal activities, if only as a way of protecting their legal residence status or of averting outright repatriation.

However, as adaptation and acculturation proceed, there are a number of scenarios that could take place. First, if adaptation to U.S. society proceeds seamlessly, the immigrant will be exposed to roughly similar conditions as the population of citizens, and consequently their involvement in crime will be comparable to that of citizens, and their response to change in economic well-being (employment and real wages) will be roughly similar to the population as a whole. If so, the overall crime rates will be affected hardly at all. As suggested above, however, if differential fertility persists for a generation or so, the result will be a higher contribution of firstand second-generation immigrants to the total pool of criminal activities and criminals apprehended.

Second, if the integration of the immigrant population is more arduous and difficult due to obstacles ranging from those associated with their human capital limitations to inflexibilities in the social system, their propensity to be involved in crime could be higher than that found in the rest of the population. This will raise the overall crime rate unless there are comparable reductions among citizens. Furthermore, to the extent that the second generation experiences even worse adaptation difficulties—as has been informally documented in the literature in other areas—the rate of criminal activity will increase and therefore will enhance the contribution to crime associated with a particular migration flow.

The second scenario suggests the possibility that first- and second-generation immigrants will be involved more permanently in criminal activities, rather than participating in them intermittently, as a foraging model would suggest. A counterargument is that shadow wages are lower among immigrants in both the first and second generation and that this should slow down or prevent altogether their involvement in crime.

Differential Fertility and Differential Adaptation

Adaptation under conditions of scarcity, poverty, and lack of access to education and training may turn out to be difficult for both the first generation of immigrants and their descendants. Insofar as higher fertility adds to the stress to which they are exposed upon arrival, one should expect a direct relation among relatively high fertility, conditions of poverty, and exposure to the risk of involvement in crime. This mechanism will ensure that subgroups of immigrants —those with higher fertility—will manifest higher propensities to become involved in crime than those among immigrants with lower fertility and than among citizens with lower comparable levels of fertility.

If all three processes described above do in fact operate, the results should be (a) an increase in the overall rate of crime and (b) an increase in the contribution to criminal activities associated with immigrants. If, in addition, apprehension of

immigrants and the subsequent judicial processes contain biases similar to those illustrated in this chapter, then (c) a disproportionate share of the population of detained and incarcerated individuals as well as an unequal share of the corresponding costs will be associated with first- or second-generation immigrants.

A simple tool to study the trajectory of the identified process is the projection of populations of citizens and immigrants by classes of age, poverty status, propensity to crime, and rates of detention and incarceration. A year-by-year accounting of the populations in the various classes can be achieved with information on fertility, mortality, and social mobility across classes. Information on propensity to criminal activity, changes in the propensity over time, and the various risks associated with the unfolding of the judicial process could be obtained from surveys eliciting self-reported criminal activity from various ethnic or national groups and from time series of arrests and incarceration, where the latter also include information on national origins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the helpful assistance of Frank Bean, Jeffrey Passel, Patricia Parker, Elizabeth Arias, Handamala Rafalimanana, and Elaine Sieff.

REFERENCES

Abbott, G. 1915. ''Immigration and Crime." Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 6(4):522–32.

Bean, Frank D., B. Lindsay Lowell, and Lowell J. Taylor 1988. "Undocumented Mexican Immigrants and the Earnings of Other Workers in the United States." Demography 25:35–49.

Brown, M. Craig, and Barbara D. Warner 1995. "The Political Threat of Immigrant Groups and Police Aggressiveness in 1990." Pp. 82–98 in Ethnicity, Race, and Crime, Darnell F. Hawkins, ed. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Butterfield, F. 1994. "A History of Homicide Surprises the Experts." New York Times, October 23:10.

Calavita, Kitty 1994. "U.S. Immigration and Policy Responses: The Limits of Legislation." Pp. 52–82 in Controlling Immigration, Wayne A. Cornelius, Philip L. Martin, and James F. Hollifield, eds. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Cornelius, Wayne A., Philip L. Martin, and James F. Hollifield, eds. 1994. Controlling Immigration. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Cressey, Donald 1969. Theft of the Nation. New York: Harper & Row.

Freeman, Richard 1996. "The Supply of Youths to Crime." Pp. 81–102 in Exploring the Underground Economy, Susan Pozo, ed. Kalazmazoo, Mich.: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Gault, R.H. 1932. Criminology. Boston: D.C. Health.

Hagan, John, and K. Bumiller 1983. In Research on Sentencing: The Search for Reform, Vol. II, A. Blumstein, J. Cohen, S.E. Martin, and M.H. Tonry, eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Hawkins, Darnell F. 1995. "Ethnicity, Race and Crime: A Review of Selected Studies. Pp. 11–45 in Ethnicity, Race, and Crime, Darnell F. Hawkins, ed. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Hayes-Bautista, D.E., L. Beazconde-Garbanati, W.O. Schink, and M. Hayes-Bautista 1994. "Latino Health in California, 1985–1990: Implications for Family Practice." Family Medicine 9:556–562.

Heer, D. 1996. Immigration in America's Future. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press.

Hirschi, Travis, and Michael Gottfredson 1983. "Age and the Explanation of Crime." American Journal of Sociology 89:552–584.

Hobbs, A.H. 1943. "Criminality in Philadelphia: 1790–1810 Compared with 1937." American Sociological Review 8:198–202.

Ianni, Francis 1972. A Family Business. New York: Russell Sage.

Isbister, John 1996. Immigration Debate. West Hartford, Conn.: Kumarian Press.

Lane, R. 1979. Violent Death in the City. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

McCord, Joan 1995. "Ethnicity, Acculturation, and Opportunities: A Study of Two Generations." Pp. 69–81 in Ethnicity, Race and Crime, Darnell F. Hawkins, ed. Albany: State University of New York Press.

National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement 1931. Report on Crime and the Foreign-Born. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

O'Kane, James M. 1992. The Crooked Ladder. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Books.

Park, R.E., E.W. Burgess, and R.D. McKenzie 1925/. The City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

1967. Passel, J.S., and K.A. Woodrow

1984. "Geographic Distribution of Undocumented Immigrants: Estimates of Undocumented Aliens Counted in the 1980 Census by State." International Migration Review 18:642–671.

Pennell, Susan, Christine Curtis, and Jeff Tayman 1989. The Impact of Illegal Immigration on the Criminal Justice System San Diego: San Diego Association of Governments.

Powell, E.H. 1966. "Crime as a Function of Anomie." Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology and Police Science 57:161–171.

Scalia, John 1996. Noncitizens in the Federal Criminal Justice System, 1984–94. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Scribner, R. 1996. "Paradox as Paradigm - The Health Outcomes of Mexican Americans." (editorial) American Journal of Public Health 3:303–305.

Sellin, Thorsten 1938. Culture Conflict and Crime. New York: Social Science Research Council.

Shaw, Clifford R., and Henry D. McKay 1942. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas: A Study of Rates of Delinquents in Relation to Differential Characteristics of Local Communities in American Cities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sorenson, S.B., and H. Shen 1996. "Homicide Risk among Immigrants in California, 1970 through 1992." American Journal of Public Health 86(1):97–100.

Sutherland, E, and D. Cressey 1978. Criminology. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Sutherland, Edwin H. 1924. Criminology. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Sutherland, Edwin H. 1934. Principles of Criminology. Chicago: Lippincott.

Taft, Donald R. 1933. "Does Immigration Increase Crime?" Social Forces 12:69–77.

Taft, Donald R. 1936. "Nationality and Crime." American Sociological Review 1:724–736.

Tanton, John, and Wayne Lutton 1993. "Immigration and Criminality." Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies 18(2):217–234.

U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform 1994. U.S. Immigration Policy: Restoring Credibility. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform.

U.S. Department of Justice 1993. Survey of State Prison Inmates, 1991. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

United States Immigration Commission 1911. Immigration and Crime Vol. 36. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

van Vechten, C.C. 1941. "Criminality of the Foreign-Born." Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 32:139–147.

Wagner-Echeagary, F.A., C.G. Schutz, H.D. Chilcoat, and J.C. Anthony 1994. "Degree of acculturation and the risk of crack cocaine smoking among Hispanic Americans." American Journal of Public Health 84(11):1825–1827.

Warren, R., and J.S. Passel 1987. "A Count of the Uncountable: Estimates of Undocumented Aliens Counted in the 1980 United States Census." Demography 24:375–393.

Wunder, Amanda 1995. "Foreign Inmates in U.S. Prisons: An Unknown Population." Corrections Compendium 20(4):4–18.