Measure the Quality of Your School Science Program

The Standards define the academic goals that your children should—and can—achieve and the characteristics of the educational system that give them their best opportunity to do so. Any plan involving achievement of academic goals and the characteristics of the educational system should have assessments to help us gauge how well the plan is working. In contrast to what most people think, assessment is more than testing or assigning grades. It can be an effective tool in achieving desired improvements. For example, it can be used by teachers to improve their instruction; it can be used as a means of communicating what is valued to students, staff, and the community; and it can help parents and others to monitor the quality of their school science program.

Assessment as a Tool for Improving Instruction and Learning

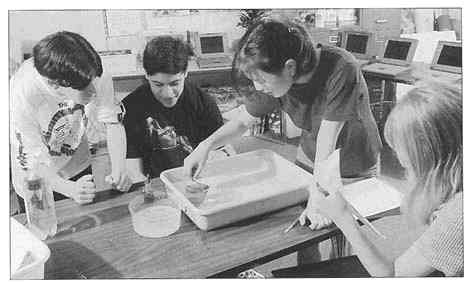

To assess a student's level of understanding, teachers traditionally have used multiple-choice and short-answer tests given at the end of a unit of study. But in a classroom where students carry out their own science investigations, these types of tests cannot possibly measure whether students have learned all that is expected of them. Better methods are needed to assess both student understanding of important science concepts and the skills they acquire from an inquiry-based curriculum, such as designing experiments, making accurate observations and measurements, analyzing data, and reaching reasonable conclusions. Alternative assessments might take the form of longer essays, portfolios of student work, observation of student performance, and oral presentations. With this variety of assessments, teachers can choose which are appropriate for different purposes. Some will help the teacher check for

student progress during a unit—not just after—and help the teacher modify his or her teaching based on the outcome.

Assessment as a Way of Communicating What Is Important

Students of all ages have always known, "If it's important, it'll be on the test." In the same way, when teachers convey what is important for students to learn by assessing it in their classrooms, they also convey that value to parents and other members of the community. Likewise, when the school board members and school administration officials decide to include science in the district or school assessments, they are indicating to parents, teachers, and students that science is an important part of the curriculum for all students. Of course, not just any kind of test or assessment will do. Just as the classroom teacher must assess the full range of understanding and skills called for in the Standards, so should district- or school-wide testing.

Using Assessment Results to Monitor Your School's Science Support System

How well students are learning what is outlined in the Content Standards is only a part of what should be assessed. Assessment of how well the educational system is supporting the type of program that is outlined in the Teaching, Assessment, Professional Development, Program, and System Standards is critical. These Standards can help you under-

stand the characteristics of the type of science program that will provide your children with the opportunity they need to learn what is expected. Assessment of the program will help you figure out what characteristics are lacking and what aspects of your school's science program need improvement. Questions you could ask include, Are the topics in your school's science curriculum consistent with those recommended in the National Science Education Standards or the state standards? Are students given adequate time and resources to learn? Are teachers given the time they need to prepare to teach science classes effectively? Are professional development opportunities available to teachers?

Your school system already may be striving to improve its science program. If such an improvement plan is underway, answers to such questions can help those responsible decide where support and resources are needed. If your school or district is just getting started on an improvement plan, comparing the results of an assessment against the expectations outlined in the Standards can provide a strong rationale for change. The next section describes how you can help bring about change in your school or district.

|

Using Assessment to Improve the Learning of Students and Teachers Assessment is a process of collecting data about part of the science education system and then using these data to improve that part of the system. For example, a teacher can ask students to interpret a graph by answering a series of questions. By reviewing student answers, the teacher immediately can decide whether to move on to the next topic or to spend more time on the current one. By examining student performance on individual questions, the teacher can tell which topics need additional time. As another example, in professional development programs, informal observations of novice teachers by experienced teachers can help determine where the novices need help. Then the professional development program can be tailored to meet those needs. |