1

Introduction

AMERICA’S YOUNG CHILDREN STAND on the brink of a new era for preschool learning, occasioned by three converging trends: (1) an unprecedented number of working mothers, creating a strong and increasing demand for child care; (2) a consensus among professionals and (increasingly) parents that the care of young children should provide them with educational experiences; and (3) growing evidence from child development research that young children are capable learners and that educational experience during the preschool years can have a positive impact on school learning. Thus, a convergence of practical, moral, and scientific considerations leads to heightened interest in the education of young children and new opportunities for the improvement of their learning and the enhancement of their lives.

There is currently no single preschool system in the United States. The public school system (kindergarten through 12th grade) is decentralized—i.e. organized by state and school district rather than by the federal government—but state school systems are similar in overall structure and the types of services offered and are tax supported. American preschools, however, vary widely in organization, sponsorship, sources of funding, relationship to the public schools, government regulation, content, and quality. If preschools are to realize the hopes of parents and educators, more attention is needed to their content, quality, and per-

formance. In this rapidly growing sector of education, there are many choices to be made concerning goals, pedagogies, programs, and means of ensuring quality.

America has come late to mass preschool education compared with other wealthy industrialized countries. Some Western European countries have long had nearly universal enrollment of young children in preschools, with high standards of teacher training and impressive curricula. What was until the mid-19th century a matter of private charity, became in the course of the 20th century a public responsibility. In most of Europe, public financing is at this point the dominant mode of support and these early childhood programs are increasingly viewed as a public obligation (Kamerman, 1999). In some countries, preschool service is free regardless of parents’ employment status or income; in others, the programs combine government funding and income-related parent fees. France, for example, provides free preschool programs for all children ages 2–6. Germany and Italy make preschool available to all 3- to 6-year-olds and social welfare child care to the children under age 3, with something less than 20 percent of costs borne by parents (see Table 1–1).

But as the United States embarks on a voyage previously taken by others, certain advantages are evident: we have a strong research community investigating early childhood learning and development and producing evidence on which to base the design, implementation, and evaluation of programs. We have a tradition of experimentation and observation in preschools that gives us access to a wealth of experience before preschool attendance becomes a universal feature of American childhood. Thus we can begin the latter part of the voyage with better maps and navigational instruments than might be expected at this point in our history; we are better able to know where we’re going and how to measure our progress. This report is intended to help prepare for the journey by reviewing what is known about early childhood development and preschool programs and suggesting how to proceed in educating young children in the 21st century.

At present, more than 60 percent of American mothers with children under age 6 are in the labor force (U.S. Department of the Treasury, 1998; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1999). There are approximately 3.8 million children in each age cohort with

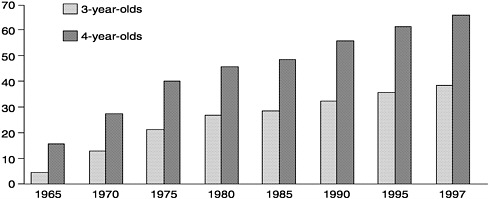

which this report is concerned: ages 2, 3, 4, and 5—figures that are projected to be relatively stable for the next decade and then rise toward 4 million (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1996). Figure 1–1 shows how steeply the enrollments of American 3- and 4-year-olds in early childhood education programs have increased over the last 35 years. In 1965, only a small minority of children (under 20 percent) was enrolled, but by 1990 the majority of 4-year-olds and one-third of 3-year-olds were. The 1997 figures (collected on a somewhat different basis) show some 65 percent of 4-year-olds and almost 40 percent of 3-year-olds enrolled in early childhood education. These figures strongly suggest that preschool enrollments are large, growing, and here to stay.

As the number of children cared for outside the home has grown, so has the conviction that education should be included in their care. Our society’s concern with the quality and effectiveness of schooling—so prominent in public discussion over the last 15 years—has naturally spread to the care of young children. There has been in the past a sharp distinction between child care, i.e., full-day programs of care for children whose parents are working, and preschool, i.e., half-day programs focused on children’s social and academic learning, but this is changing. Child care professionals increasingly define their mission in educational terms, with growing support from parents and educators. This does not mean that child care should be devoted to academic training for children under 5 any more than preschool. The developing consensus is that out-of-home care for young children should attend to their education, including school readiness, as well as providing protection and a facilitating environment for secure emotional development and sound relationships with other children and adults. A central theme of this report is that preschools, child care, and other early childhood settings must combine loving care with learning, as implied by the terms “educare” and “early childhood care and education.” We recommend it as a fundamental premise of public policy on early childhood.

Scientific knowledge of early childhood development, and of children’s learning and behavior in preschool and child care settings, has increased enormously over the past 30 years. The research findings summarized in this report show that 2- to 5-year-old children are more capable learners than had been imagined

TABLE 1–1 Early Childhood Education and Care Policy Dimensions in Selected OECD Countries

|

Country |

Locus of Policy Making |

Administrative Auspice |

Age Group Served (years) |

|

Austria |

State and local |

Welfare |

3–6 |

|

|

|

0–3 |

|

|

Belgium |

State |

Education |

2 1/2–6 |

|

|

Welfare (Center and FDC) |

under 3 |

|

|

Denmark |

National and local |

Education |

5–7 |

|

|

Welfare |

6 mos.-6 yrs. |

|

|

Finland |

National and local |

Education |

6 |

|

|

Welfare |

1–7 |

|

|

France |

National (primarily) and local |

Education |

2–6 |

|

|

Health and welfare |

3 mos.-3 yrs. |

|

|

Germany |

State |

Education |

3–6 |

|

|

Welfare |

under 3 |

|

|

Italy |

National |

Education |

3–6 |

|

Local |

Health and welfare |

under 3 |

|

|

Sweden |

National and local (primarily) |

Education |

0–6 |

|

United Kingdom |

National and local |

Education |

3–4 |

|

|

Welfare |

0–4 |

|

|

SOURCE: Kamerman (1999: Table 2). |

|||

|

Eligibility Criteria |

Funding Sources |

Subsidy Strategies |

|

Working parents |

State and local government and parent fees |

Supply |

|

Universal |

Government—free |

Supply |

|

Working parents, with special needs, poor |

Government, employer, parent fees (income-related) |

Supply and demand |

|

Universal |

Government |

Supply |

|

Working parents |

Government (local); parent fees (income-related—maximum 20–30% of costs) |

|

|

Universal |

National and local government |

Supply and demand |

|

Universal for working parents |

Parent fees income-related at 10% of costs |

|

|

Universal |

Government—free to parents |

Supply |

|

Working parents, with special needs |

Mixed local government, family allowance, and parent fees (income-related, maximum 25% of costs) |

Supply and demand |

|

Universal With special needs, poor, working parents |

State and local government plus parent fees (income-related, maximum 16–20% of costs) |

Supply |

|

Universal |

National government—free |

Supply |

|

Working parents |

Local government and parent fees, income-related, average 12% of costs, maximum 20% |

|

|

Universal, working parents, with special needs |

National and local government, parent fees (income-related, about 13% of costs) |

Supply |

|

|

Government—free |

Supply and demand |

|

With special needs, poor |

Free or income related fees |

|

FIGURE 1–1 Percentage of 3- and 4-year-olds enrolled in early childhood education (both private and public): October 1965 to October 1997. NOTE: Data for 1995 and 1997 were collected using new procedures and may not be comparable to figures prior to 1994. SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics (1998).

and that their acquisition of linguistic, mathematical, and other skills relevant to school readiness is influenced (and can be improved) by their educational and developmental experiences during those years. Such findings are helping to point the way, creating a scientifically informed basis for the construction and evaluation of educational settings and programs of instruction. Thus, the knowledge base for improvement of early childhood pedagogy has grown along with parents’ needs for more child care and the commitment to education. Research is providing both increased understanding of pedagogy and important tools for improving early childhood care and education. The opening chapters of this report present a distillation of some of the most salient issues and findings.

As America progresses toward more and better preschools, questions concerning children from low-income and educationally disadvantaged families and those with physical and mental disabilities deserve special attention. A strong finding from research is that early intervention can help prevent or mitigate the development of learning difficulties. Preschool programs can be an important vehicle for enhancing the school readiness of both groups of children. This report describes, as far as the current

state of the evaluation literature permits, the specific conditions required for optimizing their learning environments during early childhood.

Looking to the future, there can be little doubt that the United States is on its way to universal, voluntary, preschool attendance, not as the result of government mandate or expert recommendation, but as a consequence of parental demand and a myriad of private, state, and federal initiatives that are continuing to extend early education throughout the country. We are already more than half of the way there. Research suggests that there are few disadvantages and many potential advantages to taking more seriously the capacity of young children to profit from early education.

Bruner has described pedagogy as “an extension of culture [without which] we would simply fail to pass on the culture at large, to enable human beings to use effectively the vast resources that any and every culture has to offer to those within its ambit” (Bruner, 1999:12). As the upbringing of America’s children, and therefore the transmission of its culture, relies more and more on out-of-home providers of early education and care, there is a growing public interest in ensuring that this happens well and safely. Indeed, this report recommends the adoption of program standards and professional requirements. Still it is important to note at the outset that establishing standards of quality for early education in a country as large, diverse, and rapidly changing as the United States is a challenge. There is the danger that attempts to set common standards, or even to formulate what children need, may reflect the preferences of a particular group rather than the good of American children as a whole.

Promoting quality in early education need not mean insisting on uniformity. There is general agreement that the care of young children should facilitate their intellectual, emotional, and social development in ways that support their subsequent learning and social participation, in school and other settings. Beyond this, the elements of pedagogical quality with which this report is primarily concerned can be embedded in programs that are responsive to various cultural conceptions of early childhood and several alternative models of preschool education.

ABOUT THIS REPORT

Committee Charge

The Committee on Early Childhood Pedagogy was established by the National Research Council in 1997 at the request of the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Educational Research and Improvement (Early Childhood Institute) and the Office of Special Education Programs. (Supplementary support was provided by the Spencer Foundation and the Foundation for Child Development.) This cross-disciplinary team of scientists and practitioners was asked to survey a broad range of behavioral and social science research on early learning and development and to explore the implications of that research for the education and care of young children ages 2 to 5. A central purpose of the study is to help move the public discussion of these issues away from ideology and toward evidence, so that educators, parents, and policy makers will be able to make better decisions about programs for the education and care of young children. More specifically, the committee was asked to undertake the following:

-

Review and synthesize theory, research, and applications in the social, behavioral, and biological sciences that contribute to the understanding of early childhood pedagogy.

-

Review the literature and synthesize the research on early childhood pedagogy.

-

Review research concerning special populations, such as children living in poverty, children with limited English proficiency, and children with disabilities, and highlight early childhood education practices that enhance the development of these children.

-

Produce a coherent distillation of the knowledge base and develop its implications for future research directions, practice in early childhood education programs, and the training of teachers and child care professionals.

-

Draw out the major policy implications of the research findings.

In trying to build bridges between research and practice, perhaps the greatest challenge is to find ways to translate scholarly findings into a form that practitioners and others can use to review and revise policies, programs, and practices. The lack of clarity in the field of early childhood pedagogy makes this especially difficult. Many disciplines have something to say about early learning and development; there are many lenses through which one can examine issues in the education and care of young children. In the course of our work, the committee has tried to frame the issues in a way that will be useful to teachers, asking such questions as:

-

What kinds of settings enhance children’s learning in preparation for schooling? How have these settings fulfilled their educational objectives?

-

What kinds of educational programs—content and methods—have been found to promote learning and school success?

-

What has been found to limit the effectiveness of these programs?

-

What does responsiveness mean in the context of early childhood education—what do such teacher/child interactions look like?

-

What recommendations based on expert knowledge can be brought to bear to improve the status quo?

Scope of the Report

It is important to note at the outset that this is the first attempt at a comprehensive, cross-disciplinary examination of the accumulated theory, research, and evaluation literature relevant to early childhood education. The task was huge and the research both varied and of variable quality. This is not a book that offers definitive answers for all time; it does offer strong advice on applications that comport with the present state of knowledge.

The report is oriented toward research and practice in out-of-home group programs for young children. Its recommendations extend to all children, including those who are at high risk for having academic difficulties and those with identifiable disabilities. The findings are focused especially on center-based pro-

grams, since the goals and structure of these settings are the most controversial. However, there is no reason to believe that the research presented on early development and learning is less relevant to parents and caregivers at home or in parent education and support programs. It is our hope that the findings will be applied in these settings as well.

Knowledge about early childhood care and education derives from work conducted in several disciplines, in laboratory settings as well as in homes, classrooms, and child care centers, and from a range of methodological perspectives. Ethnographers, sociologists, historians, psychologists, educators, and neurobiologists, among others, study early childhood care and education. The committee has found knowledge and insight in all these perspectives and has tried to weave from them a coherent picture.

Committee Perspective

Care and Education

Based on research and on the expert judgment of its members, the committee takes as given that good pedagogy includes meeting children’s basic needs and providing emotional guidance and support, as well as motivating, instructing, and supporting their learning. There are a number of words and phrases designed to convey this idea, such as “educare” and “the whole child.” Under whatever rubric, the important point is that adequate care involves cognitive and perceptual stimulation and growth, just as adequate education for young children must occur in a safe and emotionally rich environment. Too often, education has been taken to mean a narrow focus on learning as a compiling of knowledge and skills. This is not our intent. The overriding goal of this report is to address how early childhood settings can support the full range of capacities children will need as a foundation for school and life

The importance of children’s relationships with caregivers (parents, teachers, child care professionals) is another core principle that grows out of our work. The report carefully examines research on the interactions of children and their teacher/ caregivers to determine how they influence children’s learning

trajectories (Bloom, 1964; Howes, 1997; Pianta, 1992). Although this study is about early childhood education in out-of-home settings, its emphasis on the critical role of adult responsiveness in support of the child’s intellectual and emotional development is as germane to parents as to teachers. And such family factors as parental aspirations and expectations for achievement, parental strategies for controlling child behavior, maternal teaching style, linguistic orientation, beliefs about the causes of child success and failure in school, children’s home environment, and family stress and poverty (Powell, 1997) all affect the child in preschool.

In line with Bruner’s proposition that pedagogy is an extension of culture, the committee also recognizes that families, communities, and the nation want children to grow up to be productive citizens. This requires good health, social responsibility, and psychological well-being, as well as knowledge and skills. As a consequence, we have been particularly alert to research that identifies the qualities that contribute to these goals. “Quality” as it is used in this report connotes pedagogy that cultivates the process of development and learning and is not just custodial care.

Definitional Issues

Because a number of the key terms used in this report may have varied meanings, we present below the definitions used by the committee in its work.

We use development broadly to encompass cognitive, emotional, social, and physical growth. Conceptually, development means the process of becoming “more complex or intricate; to cause gradually to acquire specific roles, functions, or forms, to grow by degrees into a more advanced or mature state” (American Heritage Dictionary, 1992). What is critical about developmental theory is that it focuses on dynamic change over time (Miller, 1989).

Pedagogy is also conceived broadly, as cultivating the process of development within a given culture and society. At its simplest, it may be defined as “any conscious activity by one person designed to enhance the learning in another” (Watkins and Mortimore, 1999:3). Pedagogy has three basic components: (1) the content of what is being taught, (2) the methodology or the

way in which teaching is done and (3) the repertoire of cognitive and affective skills required for successful functioning in the society that it promotes.

The content of teaching may be designed to encourage learning processes (memory, attention, observation) and cognitive skills (reasoning, comparing and contrasting, classification), as well as the acquisition of specific information, such as the names of the letters of the alphabet (Wiggins and McTighe, 1998).

Methods are the arranged interactions of people and materials planned and used by teachers and caregivers. They include the teacher role, teaching styles, and instructional techniques (Siraj-Blatchford, 1998); the key informing principle for early childhood pedagogy is responsiveness.

Cognitive socialization is the role that teachers/caretakers in early childhood settings play, through their expectations, their teaching strategies, their curricular emphases, to promote the repertoire of cognitive and affective characteristics and skills that the young child needs to move down the path from natal culture to school culture to the culture of the larger society.

Standards of Evidence

The methods used by social and behavioral scientists to gain knowledge in the field of education are very diverse. Here we describe very briefly the scientific standards used in conducting this review; a fuller statement appears in the Appendix.

Scientists engage in observation, description, classification, hypothesis testing, and theory building. Individual scientists are likely to focus on certain of these activities, such as observation and description, and not on others, such as theory building and hypothesis testing, depending on their own interests and the phenomena they are studying. Similarly, some domains of research involve a predominance of some forms of scientific activity to the relative exclusion of others. For instance, research on demographic trends in child care tends to be largely descriptive, whereas research on the effects of variation in curriculum tends to involve hypothesis testing.

In writing this report, we considered many types of studies, including ethnographic, descriptive, correlational, quasi-experi-

mental, and experimental forms of research. Within each body of evidence produced by these methodologies, we examined studies that flowed from strong theories, as well as those that were more inductively driven. The studies we examined were conducted for many different purposes, with a wide variety of designs and analytic strategies. Our use of these studies is based on our evaluation of their validity and generalizability and the convergence among different studies and methods.

The research base is variable. On one hand, the documentation of impressive learning abilities in young children by many methods and investigators represents a strong source of data in support of our conclusions on the need for early childhood educators to engage children in cognitively rich tasks. On the other hand, our desire to draw conclusions about the efficacy of particular pedagogical methods was frequently frustrated by the paucity of the evidence, due in part to ethical and practical limitations on research designs that can be applied in early childhood settings. In the appendix, we discuss some of these difficulties and provide some methods for addressing them.

OVERVIEW OF THE REPORT

The first two chapters following this introduction focus on the young child. Chapter 2 presents research and theory on the general processes of early development, emphasizing the ability of the environment to substantially affect developmental outcomes. It examines research on the interdependence of cognitive, emotional, and social development and explores the literature on the importance of infants’ and children’s early relationships with adults. Chapter 3 examines the numerous factors that express themselves as variation in development. These functional and status characteristics are discussed within the framework of the dimensions of variation that require particular attention from preschool teachers.

The next four chapters focus on early childhood education in out-of-home settings. Chapter 4 addresses the issue of quality in the context of five bodies of research, dealing respectively with: (a) programs designed to enhance the learning of economically disadvantaged children, (b) studies that provide empirical infor-

mation about the effects of typical variations in program quality on the general population of students, (c) studies of programs for English-language learners, (d) exemplary international programs, and (e) studies of interventions for children with disabilities.

Chapter 5 explores curriculum and pedagogy, the what and the how of early childhood education. The analysis integrates recent findings about children’s early learning capabilities (presented in Chapter 2) with research data on the general principles and approaches to early childhood care and education. Chapter 6 deals with assessment, particularly assessment to support learning. A number of assessment approaches are reviewed that hold potential as tools for preschool teachers to use to ascertain the nature of thinking and extent of knowledge for each child. Because of the vulnerability of assessment—and especially standardized tests—to misuse and misinterpretation when used with young children, the discussion emphasizes the need for caution.

Chapters 7 and 8 address the supports needed as the United States moves toward universal preschool attendance. Chapter 7 looks at the preparation of early childhood teachers and caregivers, emphasizing the need for professionalization of the field, including more and better training, to enable them to engage their charges effectively. Chapter 8 analyzes the need for program and practice standards to promote quality in early childhood education.

Our conclusions and recommendations are presented in Chapter 9.