3

BUILDING DIGITAL COLLECTIONS

TRADITIONAL COLLECTIONS: SCOPE AND RESPONSIBILITY

Collectors of books are cautious about virtualization. The artifact and the content of the artifact are so closely allied in users’ minds that the necessary theorization of virtuality—made long since by most citizens of Western nations when it comes to their own money, from banknotes and coins to credit cards and account balances—has been slow in arriving. For a library of the twenty-first century, building collections will consist necessarily of a range of activities, from the acquisition of traditional materials to something much more like what we do when we own stocks in companies whose printed share certificates we never see. Thinking through what it takes to be a great library in this new world is the central challenge librarians face in this new century.

The Library of Congress’s collection is the largest in the world. The collection is renowned not only for its scale and scope but also for its diversity and its depth in many areas. Books and serials constitute only a minority of the 119-million-item1 collection. The Library holds the world’s largest collections of motion picture films and newspapers and enormous quantities of manuscripts, prints, photographs, sound recordings, and maps. The committee heard and observed repeatedly on its visits to the Library that the Library’s collections are its primary asset.

As the largest research library in the world, the Library of Congress has had a very expansive collection policy, which it describes as follows:

The Library’s acquisitions policies are based on three fundamental principles that the Library should possess:

-

All books and other library materials necessary to the Congress and the various officers of the Federal Government to perform their duties.

-

All books and other materials which record the life and achievements of the American people.

-

Records of other societies, past and present, especially of those societies and peoples whose experience is of the most immediate concern to the people of the United States.2

In another place, LC describes its policy as follows:

The extent of the Library’s collection building activities is extremely broad, covering virtually every discipline and field of study, and including the entire range of different forms of publication and media for recording and storing knowledge. The Library has always recognized that its preeminent role is to collect at the national level. It has striven to develop richly representative collections in all fields, except technical agriculture and clinical medicine (where it yields precedence to the National Agricultural Library and the National Library of Medicine, respectively).3

The Library’s policies and practices in respect to traditional materials are sophisticated and highly evolved, reflecting decades of experience and infrastructure development. The Library uses a variety of mechanisms to build its collections (see Box 3.1), including the following:

-

Selecting published works for the permanent collection from materials that authors and publishers submit on their own initiative to satisfy the mandatory deposit requirement of the copyright law. Receipts from the Copyright Office constitute the core of the collection, particularly those in four divisions: Geography and Map; Music; Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound; and Prints and Photographs.4 Selectors examine the cartloads of materials in the Copyright Office to identify those items that will be retained for the permanent collections; approximately one-half of the published materials (and virtually none of the

|

2 |

See <gopher://marvel.loc.gov:70/00/research/collections.catalogs/collections/about/general>. |

|

3 |

|

|

4 |

Data derived from the Acquisitions Frequently Asked Questions list, available online at <http://lcweb.loc.gov/faq/acqfaq.html>. Some of the materials received through the Copyright Office are transferred to other institutions (e.g., National Library of Medicine). |

|

BOX 3.1 The Library of Congress (LC) acquires materials in all formats, languages, and subjects (except technical agriculture and clinical medicine) from all over the world, under the guidance of LC’s collection policy statements.1 On average, 22,000 items are received by the Library every working day; of these, approximately 7,000 items are selected for the permanent collections.2 The Acquisitions Directorate is organized into a fiscal office and four divisions—the African/Asian Acquisitions and Overseas Operations Division,3 the Anglo/ American Acquisitions Division, the European/Latin American Acquisitions Division, and the Serial Record Division. There are about 300 employees in the Acquisitions Directorate in the Washington, D.C., area and 300 staff members based abroad.

|

-

unpublished materials) are selected for the permanent collections.5 The remaining items are earmarked for exchange or disposal;

-

Demanding copies of selected works published in the United States from publishers who failed to submit the copies, as per the mandatory deposit requirement;

-

Selecting from works submitted for the Cataloging in Publication (CIP) program. The CIP program serves the nation’s libraries by cataloging books in advance of publication, using page proofs. It requires that publishers submit a copy of the published book to LC;6

-

Purchasing materials that add to the depth and breadth of LC collections. The Library has an acquisitions budget of approximately $10 million per year, much of which goes for purchases abroad;7

|

5 |

The Copyright Office retains unpublished work that it receives off-site for 70 years after the death of the author, but such materials are not cataloged or integrated into the Library’s collections. |

|

6 |

For additional information about the CIP program, see <http://lcweb3.loc.gov/cip/>. |

|

7 |

As reported to the committee during a site visit to the Library in July 1999. In 1999, the median acquisitions budget for members of the Association for Research Libraries was $6.3 million (see <http://www.arl.org/stats/arlstat/1999t4.html>). The Library estimates the annual value of copyright deposits selected for the collections at $23 million, and its direct purchases amount to $10 million, for a total of $33 million in acquisitions for the Library. |

-

Exchanging surplus copies with selected partners around the world. Surplus duplicates that the Library obtains are traded with U.S. educational institutions and with other selected exchange partners; LC has exchange arrangements with more than 12,000 institutions throughout the world;

-

Receiving donations (some of which are solicited) of rare books, photographs, films, sound recordings, and manuscript collections; and

-

Selecting surplus publications that are transferred to the Library from libraries in government agencies. Under long-standing policy, federal libraries are encouraged to transfer their surplus library material to LC, which has stipulated that it will accept from surplus only soft- or hard-bound books in certain categories.8

Two principles underlie the development of the collections: careful selection and stewardship. Selection has always been important in building LC’s collections, even though its mission is to acquire, organize, preserve, secure, and sustain—for the present and future use of the Congress and the nation—a comprehensive record of American history and creativity. The Library organizes its collections either by topical area or into special collections that are further subdivided by media or form of material (see Box 3.2). Selectors on the Library staff use their expertise in subjects, area studies, and special formats and their knowledge of LC’s collections to guide decisions about which materials should be added to the Library’s physical holdings. Once materials are selected for inclusion in the collections, the Library assumes a number of associated stewardship responsibilities that include preserving collections to ensure long-term viability and providing for intellectual access to materials. These responsibilities are discussed at length in Chapters 4 and 5.

THE CHALLENGES OF DIGITAL COLLECTIONS

The rapid growth of digital materials will challenge the Library in what it tries to collect, how it carries out its collecting role, and when and how it permits users to access its collections. Although there are many direct analogies between digital and physical collections, there are also significant differences. The digital era has brought with it a wide range of new types of intellectual creations and new means for authors to distribute their works. Some of the most important digital resources today

|

BOX 3.2

SOURCE: Derived from <gopher://marvel.loc.gov:70/00/research/collections.catalogs/collections/about/outline.of.collection.overviews>. |

represent new types of materials without easy analogy to the world in which the Library’s collections policies were written, such as social science datasets, geographic information systems, scientific data with visualization tools, digital images, and the ubiquitous Web page.9 Many of these new materials do not fit easily into traditional collecting categories because they cross the boundaries of established topical areas, nor do they coincide with the conventional categories in “special formats.”

Not only are many new types of materials being created, but the way in which they are distributed also differs significantly from the methods of the past. The Library’s collecting methods are now tuned to books, serials, and other tangible artifacts that flow into the Library through a variety of well-established channels. Some new digital materials are following different paths; others never arrive. These materials frequently are being distributed by different types of organizations, using new business and economic models. E-journals and e-books, which today bear a fair resemblance to their paper predecessors, are being distributed primarily through Internet-based subscriptions in which the publisher or distributor permits access to a remote site rather than providing a copy of a journal or book. A collecting model that relies on vendors providing copies of resources for processing and storage at the Library will not suffice for digital materials, especially when the item in question is dynamic and changes frequently.

Probably the most active area of digital publishing today is taking place on the World Wide Web. Much of this publishing does not follow the dominant commercial model of the past century. Individual authors and organizations make a wide variety of information available through the World Wide Web in order to disseminate their ideas, to gain recognition, and possibly to provide a venue for advertising. Often there are no publishers, at least in the traditional sense, to act as intermediaries between the creator of the works and the Library. Yet some of these digital works are as important as records of current research and creativity as were the journals and books of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries.

Traditionally, libraries have served geographically or institutionally local audiences. Local residents visit a library building to access books and artifacts in its collection. If a particular artifact is not available locally, it can be obtained through elaborate procedures developed to locate the desired item and transport it to the customer—but even then, the basic

library model is essentially unchanged from a century ago. With the advent of a wide range of new computing and communications technologies, however, this traditional model will probably not survive the present decade. In the future, most objects will no longer exist in a specific physical space, and access to digital objects will no longer be limited to those who present themselves at a particular location. Over time, the new technologies will eliminate the association between geography and a library’s customers. Of course, the physical artifacts of the past will persist, and many will not be committed to digital form for a long time, if ever.

This shift from artifact to virtual information has only just begun to influence the Library. For example, most of the people seeking access to LC collections are required to visit the Library in Washington, D.C. Whether they wish to read a foreign newspaper, search out an unusual journal, inspect a rare book, or do in-depth research in a particular subject area, they have to transport themselves to the desired resources. There have been some limited exceptions, such as access for members of Congress and the visually handicapped and borrowing through interlibrary loan. But in an increasingly wired world, the balance between on-site and remote access has the potential to shift radically. Digital materials, regardless of where they are physically housed, could, in principle, be accessible from any location where the appropriate constellations of technology are available. In addition, these materials could be accessed by many people at the same time, or an individual could easily access multiple sites concurrently.10

Providers of information protect their intellectual property rights in ways that complicate the task of providing access to digital materials. Where a traditional book has a natural limit of one user at a time, digital information can, in principle, be used by unlimited numbers of people more or less simultaneously, to such an extent that publishers fear a substantial loss of sales. Academic and other research libraries have addressed this issue primarily by negotiating licensing agreements with publishers and distributors of digital works. Licensing agreements can define the community of users who at any given time have access to a resource; for example, they may allow access only to members of a well-defined community, such as the students, faculty, and staff of a particular

university.11 But apart from members of Congress and federal government employees who need access to the Library’s collections to carry out their work, the Library lacks an easily definable user community. Today’s fundamental changes require a reexamination of what a library needs physically to collect, what it can rely on others to hold while providing users with remote access, and under what conditions it can provide access to which users. There are experiments abroad with “national site license” models that seek to ensure the broadest possible access, but neither libraries nor publishers have pursued such models with any success in the United States.12

Because of the dynamic, rapidly changing nature of many digital resources, the Library also needs to be more energetic in its approach to collecting digital information. Much of the information that was available at one time on the Web is already lost because no institutions had the foresight to copy and preserve it before it was changed or deleted. Estimates of the average life of a Web page vary, but the basic conclusion is the same: it is short.13 Within a matter of a few weeks or a few months, much of the information available on the Web is updated, augmented, or simply deleted. In the digital environment, all libraries have to decide quickly what information should be included in their collections and then negotiate with rights holders over the terms and conditions for managing and providing access to these materials. The committee believes that these differences require the Library to reexamine its policies and to devise new infrastructures reflecting the very different nature of digital materials.

The committee believes that LC needs to be not only more ambitious but also more selective in the methods it uses to build digital collections. Increased attention to selection is necessary because of the explosion in digital information of widely varying quality and interest. The Library cannot be expected to collect everything, especially if collecting carries

|

11 |

Because digital materials can be easily copied and viewed by a large number of people, publishers have a legitimate concern about their accessibility. Any number of economic models are being investigated, including pay-per-view and licensing arrangements that put restrictions on which and how many users may view the licensed materials. Publishers fear that, in the worst case (from their point of view), an institution like LC could obtain a single digital copy of a journal and make it available over the Internet, at which point the market for additional copies could effectively disappear. |

|

12 |

See <http://www.library.yale.edu/~llicense/national-license-init.shtml> for current information about such initiatives. |

|

13 |

Brewster Kahle pointed out that research at the Internet Archive finds half of the Web disappearing every month—even as it doubles every year. “The mean life of a Web page is about 70 days,” he said. See “No Way to Run a Culture,” by Steve Meloan, in Wired News, February 13, 1998. It should be noted that estimates of the mean life of a Web page vary. |

with it an obligation to preserve what it collects. The number of authors and publishers in the existing print publication environment is large, heterogeneous, and distributed. Nonetheless, after several centuries of bibliographical development, a great deal of control has been achieved to provide libraries and users with thorough and systematic information about what has been published. By comparison, the world of Internet publishing is new, raw, and wild. New models for defining Library collections require a redefinition of what constitutes a library’s “collection.” With digital materials, no longer is it necessary for a library to hold an item physically to provide its users with access. Remote access challenges one of the fundamental assumptions of current collection policies: that a library needs physical control of an item to assure its users access. Nowadays, a library may provide intellectual access to distributed digital works without ever owning them or hosting them on its systems. A library might provide access to current materials for a limited period of time and then relinquish long-term preservation responsibilities to another organization. It might enter into cooperative arrangements and partnerships with other libraries, publishers, consortia, and commercial service providers for some or all of the activities associated with stewardship of physical items.

DEFINING AND BUILDING COLLECTIONS IN THE DIGITAL ERA

Defining the Scope of “Collecting” Responsibility

Traditionally, the boundaries of collections have been determined by the ownership of tangible objects. Most of the decisions made about collections—about acquisition and deaccession, cataloging, preservation, and access—have been made by the local institution that houses and/or owns them. This makes sense for collections comprising discrete physical objects—books, serials, maps, and the like. For collections of digital objects—either born digital or digitized from other media—the notions of collection and collection maintenance need to change because ownership and physical proximity to collections are no longer prerequisites for access to materials. Technically at least, copies of items in a digital collection can be accessed from anywhere, provided the right combination of hardware and software is available. With digital resources, the issue of access can be separated from that of stewardship. Therefore, an important question facing LC and all other libraries is how to define their digital collections. This question has significant implications for LC in terms of what to collect, which mechanisms to use to build its collections, and how to sustain over time those digital materials that constitute part of the comprehensive record of American history and creativity.

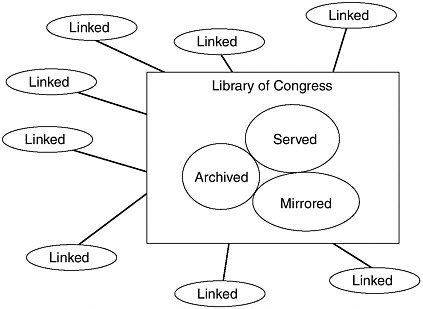

FIGURE 3.1 Digital collections and the universe of information—a possible model.

The Digital Library program of the University of California at Berkeley offers one possible model for defining a library’s responsibilities for collecting and maintaining digital works (see Figure 3.1).14 That digital library identifies four levels of collecting defined by where the information resides and what level of commitment the library makes to management and long-term preservation:

-

Archived—The material is hosted at the Library and the Library intends to keep the intellectual content of the material available on a permanent basis.

-

Served—The material resides at the Library but the Library has not (yet) made a commitment to keep it permanently.

-

Mirrored—The Library hosts a copy of material that also resides elsewhere and the Library makes no commitment to maintaining the contents. At this level, another institution has responsibility for the content and its maintenance.

-

Linked—The material resides elsewhere and the Library points to that location but has no control over the information (the portal model).

|

14 |

“Digital Library SunSITE Collection and Preservation Policy,” University of California at Berkeley, available online at <http://sunsite.berkeley.edu/Admin/collection.html>. |

One underlying principle is that material in any category other than the archived collection may be shifted from one category to another to meet changing user needs, to improve remote server responsiveness, to address intellectual property issues, or to reflect changing assessments of the value of the material. Some such model must emerge if the Library is not to become an island cut off from increasingly large portions of the creative output of American and world cultures.

The burden of preserving digital collections is enormous. The committee believes that this burden must necessarily be shared among a variety of archiving institutions (see Chapter 4). To ensure that all important research materials are preserved for future generations, it is important that archiving institutions understand the scope of each other’s stewardship roles, as is the case with hard-copy publications.

Recommendation: The Library should explicitly define the sets of digital resources for which it will assume long-term curatorial responsibility.

Fulfilling the archiving and preservation responsibility is a long-term effort that will serve researchers for generations to come. The Library also has a responsibility, however, to provide access to a much wider and more comprehensive body of resources for current use. Its current acquisitions policy identifies Congress and various government officials as one specific audience. The extent to which the Library can or should emphasize audiences beyond this core set of users is of considerable significance for the overall collecting strategy.

Recommendation: For digital resources for which the Library does not assume long-term curatorial responsibility, the Library should work with other institutions to define appropriate levels of responsibility for preservation and access. Some materials that the Library acquires and makes available to its users may have only temporary value; other materials may be hosted on a Library site for more efficient access, with long-term archiving responsibilities accepted by another party.

Recommendation: The Library should selectively adopt the portal model15 for targeted program areas. By creating links from the Library’s Web site, this approach would make available the ever-increasing body of research materials distributed across the Internet. The Library would be responsible for care-

fully selecting and arranging for access to licensed commercial resources for its users, but it would not house local copies of materials or assume responsibility for long-term preservation.

Mechanisms for Building Digital Collections

Libraries have built complex infrastructures to handle physical collections. People and systems are in place to order, receive, process, and catalog materials. There are stacks in which to store materials, binding services, and systems for identifying and locating materials and for circulating them to users. The people who keep libraries running have a deep knowledge of their physical collections, where to find new materials to add to the collections, and how to assess their value. All of these functions have analogues in the digital world, but the specifics of the required infrastructure differ, reflecting the differences in the nature of the objects, the suppliers and users, and the business and service models involved. How digital materials are identified and selected, how they are received and inspected for quality, where they are stored, how they are described in metadata (see Chapter 5), and how they are made available to users—all require the redesign of existing systems, new systems and new relationships with providers, and new skills on the part of library staff. Many of the mechanisms that the Library of Congress will use to build its digital collections resemble those used by other large libraries. But LC also has some unique responsibilities (e.g., acquiring a comprehensive record of American life, achievement, and creativity) and unique mechanisms to help it meet these responsibilities, especially copyright deposit.

Copyright Deposit

The Library’s role in registering copyright and enforcing the mandatory deposit law (discussed at length in Chapter 2)16 creates a unique opportunity for it to collect digital information that might otherwise vanish from the historical record. In conjunction with the Corporation for National Research Initiatives (CNRI) and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Library has been working on the Copy-

right Office Electronic Registration, Recordation and Deposit System (CORDS) project since 1993. The current intent of CORDS is to permit certain applicants to prepare copyright registration applications, deposit digital materials, and handle transactions with the Copyright Office via the Internet. Approximately $900,000 is spent on CORDS per year: about $600,000 is provided to CNRI (through a DARPA contracting mechanism, to which DARPA itself has contributed a total of more than $1 million for development costs), with the balance allocated within LC for two full-time equivalents (FTEs) in ITS, staff in the Copyright Office, and hardware and software.

As a research and development activity, the CORDS project has helped the Copyright Office staff develop and evolve their thinking on information systems, and for that reason, CORDS has been helpful. However, the committee is concerned about the current and planned scale of deployment. A very small percentage of the Copyright Office’s workload in the year 2000 is handled by CORDS, and the expansion plan for the year 2004 projects only 100,000 digital deposits (less than 15 percent of the projected total of 725,000 deposits) will be handled through CORDS.17 CORDS is currently available to a handful of publishers with copyright accounts and the appropriate technological infrastructure. Individuals and most publishers wishing to deposit digital materials electronically cannot use the system. An operational system is urgently needed (whether it is CORDS or something else) and must be deployed in an expeditious manner. The Copyright Office plans to draft a statement of work in FY01 and to obtain the services of a vendor to develop a production system beginning in FY02. It is imperative for the Library’s digital future that this vendor solicitation process take place as scheduled or, preferably, sooner. The drafting of the statement of work should be informed by the lessons learned from the Integrated Library System project and completed carefully, considering the needs of the Copyright Office and Library for ongoing technical support, maintenance, and flexibility (in the context of the evolving digital environment and reengineering within the office18).

The production system for digital registration and deposit, whether it

is an evolved CORDS or a new system, must fit into an infrastructure that would help the Library augment its comprehensive physical collections with digital works. The Copyright Office is one of the primary points of entry for physical materials into the Library’s collections, and one would expect CORDS to be carefully integrated with a repository system where the Library’s electronic collections will be maintained.19 Selectors from Library Services must be able to select digital works for the Library’s collections, to transfer them to the permanent collection, or to preserve them. Electronic copyright deposit is a strategic tool the Library will require in the digital world. It cannot risk being technically unprepared to deal with electronic copyright deposits and the smooth addition of such materials into its permanent collections.

The design for the Library’s production system should not be unduly constrained by current work processes for the registration and deposit of physical artifacts, because the new system needs to support the Copyright Office of the future (and also because those processes are likely to evolve under the planned reengineering effort in the Copyright Office). However, the rapid proliferation of digital objects (described in Chapter 1) demands that the design for the production system move forward in parallel with reengineering efforts at the office.

The committee addressed the specific technical question of whether the production system should be developed anew or based on an evolution of CORDS. It interviewed the principals at LC and CNRI and former staff of CNRI. Given that these discussions resulted in varying points of view and that the committee did not assess the CORDS architecture or program code directly (such an assessment was thought to be beyond its charge), the committee did not arrive at a consensus on the question of technological revolution or evolution, although the members did agree that a new system deserves serious consideration.

Finding: The Library urgently requires a production-quality system for receiving and managing digital objects deposited with it and registered for copyright. Such a system will enable the Library to enforce the deposit requirement for born-digital materials.

Finding: The new production system needs to integrate well with other Library systems; the new system should at the same

|

19 |

Determining who may access work digital works is not an easy matter, given the challenges posed by copyright and licensing issues. |

time make it easier for providers of information to register and deposit their works.

Recommendation: The Copyright Office should complete the statement of work for a production system in FY01, as planned, and as soon as possible (e.g., by the end of calendar year 2000). To achieve this goal, the resources and attention of Library-wide senior management should be directed to the Copyright Office, perhaps on a scale and with visibility comparable to those of the Integrated Library System implementation. The committee urges the Congress to support and fund the acquisition of a production system for receiving and managing digital objects.

Another copyright issue has to do with the preferred format for the deposit of materials available in electronic form. Current deposit requirements discourage the digital deposit of complete digital works, except for those represented in a tangible form, such as on a CD-ROM. According to its best-edition statement,20 the Library generally favors tangible items over digital versions, illustrated by its preference for CD-ROMs and printouts of digital information. Authors wishing to register copyright for digital work may deposit either a complete version of the work on CD-ROM or a printout of selected portions of the work. The deposit requirement for registering software is a printout of the first and last 25 pages of the source code. This policy, developed before the Internet made it easy to transfer digital information through networks, is no longer justifiable or effective.

Finding: The Library’s mechanisms and policies for the deposit of digital works currently favor printouts or tangible forms (such as CD-ROMs) over digital editions of digital works. This strategy is shortsighted because an increasing amount of born-digital information cannot be represented in tangible form and is much less useful if reduced to print or analog form. Tangible physical objects also require extensive physical handling for registration, cataloging, shelving, retrieval, and use.

Recommendation: The Library should set new standards for

|

20 |

When materials are published in more than one format, the Library specifies the format to be registered and/or deposited. This is referred to as the “best edition.” The applicable circulars are available online at <http://www.loc.gov/copyright/circs/>. |

the appropriate formats for digital materials acquired through copyright deposit, purchase, exchange, and donation and should review those standards annually. The concept of “best edition” must be revisited to remove the present bias in favor of paper versions. Each class of materials should be considered separately, depending on its specific physical and digital properties for current access and preservation purposes.21 The complexity of these issues will increase as the digital environment evolves. Accordingly, the Library must have an ongoing capacity to monitor these issues closely and systematically and have sophisticated staff involved in the deliberations.

Licensed Resources

The Library’s mandate for copyright registration and deposit provides a unique opportunity to capture and preserve digital information. But voluntary deposit is only one of several methods that the Library must use more aggressively to build its digital collections. One of the most important applications of CORDS thus far has been the copyright registration of dissertations. Through a cooperative agreement with ProQuest (formerly Bell & Howell Information and Learning or University Microfilms, Inc.), dissertations and theses can now be registered and deposited electronically. The agreement designates ProQuest’s Digital Dissertations database as the official off-site repository for the more than 100,000 dissertations and theses converted to digital form since 1997 and registered electronically. The agreement also provides for the Library to obtain a digital copy of the dissertations and theses should ProQuest cease to maintain the database. This is an example of an LC collection that resides off-site but that would move to the Library’s archived collection if ProQuest stopped maintaining it. The agreement illustrates one way of controlling access to a linked collection: users who come into the Library’s reading rooms can gain access to the ProQuest Digital Dissertations database, but they may not access the database remotely through LC.

The committee is concerned, however, that sufficient attention has not been given to the mechanisms by which LC would respond if a provider failed to maintain the material. It is also unclear whether the ProQuest arrangement, even if it proves successful, is scalable as a gen-

|

21 |

See the discussion in Chapter 1 on the recent and dramatic rise of e-books. Consideration will have to be given in the very near future to the question of when the best edition of a popular new novel is the digital file from which both paper and electronic copies are derived. |

eral-purpose model for the Library. Nevertheless, the committee commends the Library for taking this initiative and urges it to view the ProQuest arrangement as an experiment—that is, it should also consider alternative models (e.g., the inclusion of a third-party agent that would hold digital information in escrow and release it to the Library if the vendor ceased operations).

Recommendation: The ProQuest agreement serves as an interesting experiment in how the Library might handle digital collections. In such arrangements, the Library must pay particular attention to its legal rights and responsibilities in the event of default. It must establish and regularly test its capacity to accept and make available such collections if it should be called on to do so.22

Today, many publishers and distributors enter into licensing agreements that permit registered users to access digital materials online. Most licensing agreements prohibit wholesale copying and redistribution and place limits on printing or downloading digital information. The Library already licenses many electronic information services, both for CRS and for on-site Library users. Depending on the terms of the license, when such a subscription is canceled the information may no longer be accessible to the Library of Congress’s users. Where licensed digital distribution is the only means of access, business decisions by the publishers and distributors may determine what information is preserved and remains available in the long run—which poses the risk that important scientific or cultural information could be lost because its retention was not profitable. If it concludes that a work makes an important contribution to the national collection, the Library may need to enforce aggressively the copyright law that requires publishers to deposit copies of works published in the United States. Capturing important digital content that is controlled by licensing agreements will require LC to take aggressive measures, including negotiating special licenses with publishers.

Recommendation: The committee believes that the Library is in a unique position to demand the deposit of some digital materials and to require agreements for shared custody or fail-safe preservation should the materials become unavailable; it should do so.

Collecting Web-based Resources

The Web has become a powerful new paradigm for the dissemination of information of many kinds. While it is used to distribute commercial and licensed products, much of what is available is being freely distributed by its creators. Web publishing is one of the most original features of contemporary American life. It is hard to imagine how the scholars of the future will analyze and document American culture at the end of the twentieth century and beyond without having access to a great deal of this material. No effort to maintain a comprehensive collection of American creativity will be credible without it.

Some national libraries are using their countries’ mandatory deposit laws actively to collect digital documents. One of the most aggressive programs to collect and preserve digital documents is the Web archiving program operated by the Swedish Royal Library. Using Web crawler technology similar to that developed by the Internet Archive (see Box 3.3), the Swedish Web archiving project is creating a digital collection of all publicly accessible Swedish Web sites. The Swedish Royal Library considers publicly accessible Web sites “publications” that are subject to mandatory deposit.23 A similar effort is under way in Finland, and the Canadian National Library and the Australian National Library have programs for selectively collecting and preserving national content distributed via the Web.24 The challenge of capturing significant American content on the Web is much more daunting than any of the efforts mentioned here,25

|

23 |

The Swedish Web archiving project is described at <http://kulturarw3.kb.se/html/projectdescription.html>. |

|

24 |

Information about Project Eva in Finland may be found at <http://renki.lib.helsinki.fi/eva/english.html>; information about digital projects at the National Library of Canada may be found at <http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/digiproj/edigiact.htm>; information about the Pandora project in Australia may be found at <http://www.nla.gov.au/pandora/>. |

|

25 |

While the size of the U.S. portion of the Web is unknown, it is certainly enormous. Perhaps half of the Web sites in existence today are based in the United States. In October 1999, researchers at OCLC estimated that the World Wide Web had about 3.6 million sites, of which 2.2 million offer publicly accessible content. These sites contain nearly 300 million Web pages. The largest 25,000 sites represented about 50 percent of the Web’s content, and the number of sites and their size are climbing (see “OCLC Research Project Measures Scope of the Web,” an OCLC press release, Dublin, Ohio, September 8, 1999. Available online at <http://www.oclc.org/oclc/press/19990908a.htm>). |

|

BOX 3.3 The Internet Archive is a nonprofit foundation located in San Francisco and founded by Brewster Kahle. Since 1996, it has been collecting HTML (and some FTP and gopher) pages monthly. It currently contains 14 terabytes (i.e., a billion pages). A recent Web crawl collected about 450 million pages. The staff believes that it collects about 90 percent of the public static HTML pages. The Internet Archive hopes to record audio, video, and other Web content soon. It is starting to collect all the images on the Web pointed at by the pages it collects and also to explore the possibility of recording television broadcasts. The collection is open to anyone over the Internet, but some programming skills are required to use it. Notable Internet Archive users include the Smithsonian Institution, which built a collection of the 1996 presidential election Web sites. The archive has also worked with IBM Corporation researchers and intellectual property lawyers, and it is collaborating actively with researchers from Compaq and Nippon Electric Co. (NEC). The Internet Archive is still evolving: the staff want it to be a center for research, a destination, and a catalyst for innovation. It hopes to be both a service organization and an active community of scholars exploring the archive’s contents. When asked what lessons they had learned, the staff replied that building the archive is technically much harder than one might imagine. Managing data volumes measured in terabytes puts them well beyond the scale of off-the-shelf tools. Everything must be done with great attention to scalability. Most tools break immediately when used on this scale. The archive has worked closely with Alexa1 (now a subsidiary of Amazon.com), which has provided it with various Web crawls over the last 4 years. The archive has its own building, computers, and storage and maintains close ties to Alexa but is now operating independently of it. It is slated to have a staff of between 20 and 50 (as of May 2000, it had a staff of 5). SOURCE: Testimony at the committee’s September 1999 plenary meeting, information at the Internet Archive’s Web site at <http://www.archive.org>, and a site visit to the Internet Archive by committee members Jim Gray and David Levy on December 14, 1999.

|

yet the initiatives in other nations offer solid technical and policy models for active collecting programs led by U.S. national institutions.

The Library of Congress recently launched a project with researchers at Cornell University to capture Web sites from the year 2000 election campaigns. The committee applauds this effort. Not only will it bring important documentation of American life and culture into the Library’s collections but it will also allow Library staff to become familiar with techniques for pulling materials from the Web and will expose the Library to a variety of policy and technical issues associated with proactively

collecting materials from the Web. This effort will also help to articulate a definition of digital publication, thereby helping to clarify which digital materials are subject to mandatory deposit. The committee recognizes that such an undertaking is fraught with legal, technical, intellectual, and practical difficulties (see Box 3.4).

Recommendation: The Library should aggressively pursue clarification of its right to collect copies of U.S.-based Web sites under the copyright deposit law. If questions about this right remain, then LC should seek legislation that changes the copyright law to ensure that it has this right. This right would not necessarily include the right for LC to provide unlimited access to the Web sites collected.

Recommendation: The Library should conduct additional pilot projects to gain experience in harvesting and archiving U.S.-based Web sites. Such projects should be carried out in partnership with experts or organizations that have the requisite expertise.

Recommendation: The Library should quickly translate the experience gained from pilot projects into appropriate collecting policies related to U.S. Web sites.

Building Infrastructure for Digital Collections

To acquire, organize, service, and preserve digital collections of the same breadth, depth, and value as its physical collections, the Library of Congress needs to develop an infrastructure of systems, policies, procedures, and skilled staff equivalent to the infrastructure in place for its physical collections. The Library has begun to address some of its infrastructure needs as part of the NDLP. However, the committee believes this effort needs to be increased significantly and reoriented from meeting the specific needs of its own digitized special collections (which has dominated the focus of the NDLP) to the purchase, deposit, and aggressive collecting of born-digital materials. The elements of this infrastructure include reorienting existing methods of acquisition, such as copyright deposit, to the acquisition of digital materials.

The Library requires a generalized infrastructure to support a much wider set of heterogeneous digital resources from a wide variety of sources. The NDLP gave the Library a great deal of experience in receiving and integrating into its systems materials that had been converted under contract by vendors. It also has gained very limited experience

|

BOX 3.4 Archiving Web space is an enormously challenging task, one that is only beginning to be taken on and in only a small number of institutions. The key issues that an archiving effort must address include the following:

|

with taking in digital copyright deposits (see discussion of CORDS above). The problems of taking in and making available heterogeneous materials from a wide variety of sources of varying technical sophistication will be challenging. The Library will need to develop significant expertise in an ever-expanding list of varied digital formats and the ability to transform received items into supported formats. The experience of libraries that have loaded commercial electronic journals into local systems has demonstrated the need for good tracking and quality control systems to ensure the receipt, completeness, and functionality of electronic information. Furthermore, if the Library is to pursue the collection and preservation of Web-based publishing, then it will need to build specific skills and facilities to harvest and validate such data. Finally, bringing more digital materials into the Library’s collections will inevitably raise questions about the terms and conditions under which users will be able to access materials remotely. The Library will need expert staff to manage negotiations with publishers and other rights holders and to administer complex licensing agreements.

Neither this committee nor any group of consultants can recommend details of the technical infrastructure that the Library needs until the Library refines its collecting aims and stewardship responsibilities for digital collections. For example, the number, size, and technical specifications for one or more digital repositories will depend on the characteristics and relative size of the collections that the Library decides to host on its own systems as opposed to creating links to remote sites or entering into partnerships with third parties that will serve as off-site repositories, as in the ProQuest agreement. The committee agrees on the general outline of features that would be highly desirable for such an infrastructure. Mechanisms for depositing digital materials, whether through copyright deposit, licensing, or purchase, should be highly automated and easy to use. Repositories for storing digital materials will need to support long-term preservation requirements (discussed in Chapter 4) and the various metadata schemata for organizing, describing, and managing heterogeneous digital collections (discussed in Chapter 5). Robust security to prevent loss, alteration, and unauthorized access, in conjunction with complex rights management requirements, will also be needed.

Recommendation: The Library should put in place mechanisms that systematically address the policies, procedures, and infrastructure required for it to collect diverse types of digital resources and to integrate them into its systems for description and cataloging, access, and preservation.

Recommendation: Throughout the Library and particularly in Library Services, the acquisition and management of digital collections will require that the professional librarians have high levels of technological awareness and ability. The Library needs to undertake job redesign, training, and reorganization to achieve this goal.