Finding 1

Timely Selection of Scientists and Engineers Is Important

Before and after the presidential election, the eventual President-elect needs advisors with expertise in science and technology (S&T) to advise on policy issues and help to locate a candidate for the position of Assistant to the President for Science and Technology (APST).

The Carnegie Commission on Science, Technology, and Government's report Science & Technology and the President 2 identified key areas where the President will need S&T advice. These include

-

National Security

-

Space Policy

-

Civilian Technology and Economic Competitiveness

-

Health

-

Environment

-

Large-scale S&T programs

-

Scientific and Technical Education and Research

-

Government Technical Personnel.

However, the array of issues where S&T guidance is critical is even broader than the Carnegie Commission list. A scan of the positions identified by the panel as the top S&T positions (see report) includes almost every cabinet department.

-

Agriculture

-

Commerce

-

Defense

-

Education

-

Energy

-

Health and Human Services

-

Housing and Urban Development

-

Interior

-

State

-

Transportation

-

Veteran Affairs

-

Environment

-

Space

-

Science

The President-elect needs advisors who have expertise in S&T to advise on such policy issues. This advice not only deals with science and engineering research policy, but is also based on scientific and technical analysis to inform the eventual President-elect so that wise decisions can be made. These advisors can also help locate a candidate for the position of APST.

Soon after the election, the APST candidate is needed to help set priorities, plan strategy, advise the President-elect and cabinet designees, and find qualified candidates for key S&T positions.

Even before inauguration, a new president must address a number of issues that will affect the success of the new administration's S &T policy. The Carnegie Commission on Science, Technology, and Government 3 summarized these issues as follows:

-

Set initial policy priorities for the new administration.

-

Resolve budgetary questions concerning S&T investments in defense, space, health, energy, and other major programs that will affect the first budget message to Congress.

-

Make several dozen key S&T appointments.

-

Organize the White House and Executive Office staffs.

The Carnegie Commission report goes on to delineate the reasons that the new president needs direct and frequent access to trusted expertise in dealing with S&T issues. Providing this perspective is the reason for the office of Assistant to the President for Science and Technology. 4 Because these issues require attention at the very outset of the new president's term (especially issues related to the first budget message), the President can benefit from trusted advice immediately. And because a president can afford to trust high-level advice only when he has confidence in the person delivering it, a personal as well as professional relationship with an APST needs to predate the start of an Administration.

To be effective in such a highly visible and complex position, the APST must have multiple attributes. The person must be a distinguished scientist or engineer who has the respect of the scientific community, the trust of the President, and good working relationships with other key presidential advisers. He must also have experience in making policy decisions to assist the President across a wide agenda of issues.

Once the term of office begins, the APST, according to the Carnegie Commission report, has six main responsibilities:

-

Advising and assisting the President and his staff.

-

Participating in the formulation of policy involving S&T.

-

Advising the President on funding priorities for S&T.

-

Tracking the implementation of S&T-related policies.

|

2 |

Carnegie Commission on Science, Technology, and Government. 1988. Science & Technology and the President. New York: Carnegie Commission. www.carnegie.org/sub/pubs/science_tech/nextadm.htm |

|

3 |

Carnegie Commission on Science, Technology, and Government. 1988. Science & Technology and the President. New York: Carnegie Commission. www.carnegie.org/sub/pubs/science_tech/nextadm.htm |

|

4 |

Presidents traditionally have sought S&T advice from outside the government. A formalized structure for receiving this advice began in 1957 with the launching of Sputnik, when President Eisenhower brought James Killian into the White house as Special Assistant to the President. In 1972, President Nixon removed the science-advising function from the White House, but it was restored by President Ford in more or less its present form. |

-

Alerting the President to new developments in S&T and their policy significance.

-

Helping agencies to respond to emergencies, such as electricity blackouts, technoterrorism, computer breakdown, and natural disasters.

The APST has to work closely with other senior members of the President 's staff, such as those at the Office of Management and Budget, and with Cabinet members as they come together in the National Security Council, Domestic Policy Council, and National Economic Council.

The APST also serves as director of the statutory Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). 5 OSTP is charged with helping to:

-

Advise the President of S&T considerations involved in areas of national concern.

-

Evaluate the scale, quality, and effectiveness of the federal programs in S&T.

-

Advise the President on S&T considerations with regard to the federal budgets.

-

Assist the President in providing general leadership and coordination of R&D programs of the federal government.

The other PAS appointments of importance in OSTP are four associate directorships, which also must be filled as soon as possible in a new presidency. These posts should be used to reinforce the policy functions of the office and to improve the collaboration between OSTP and the offices and councils in the Executive Office of the President.

Long-standing vacancies in top positions seriously disrupt the smooth operations of the government and make management improvement exceedingly difficult, if not impossible. 6

The APST must perform essential tasks from the point of view of the broader recruiting effort. The challenge of recruiting is compounded by the fact that scientists and engineers (S&Es) do not usually consider a term as a political appointee to be a normal step in their careers. A well-connected and dedicated APST can speak to such colleagues as a peer, using a common language and set of professional values. Personnel in the Office of Presidential Personnel (OPP), in contrast, might not possess S&T expertise and might be handicapped when approaching S&T candidates.

The APST is seen as a national role model and can do much to improve White House outreach to the S&T community and to encourage the White House, industry, academe, and disciplinary societies to work together in expanding the pool of candidates.

In attracting the best S&Es for these leadership positions, the importance of presidential leadership is paramount, even where cabinet secretaries and agency heads take the lead in identification and recruitment. When the President is perceived in the S&T community as someone who understands the value of science, it becomes easier to recruit and select the most talented S&T candidates.

|

5 |

OSTP was mandated by the National Science and Technology Policy, Organization, and Priorities Act of 1976 (P.L.94-282). |

|

6 |

See U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO), Service to the Public: How Effective and Responsive is the Government?, GAO/T-HRD-91-26 (Washington, DC: US General Accounting Office, May 8, 1991. A broader finding of this report is that “good management requires stable leadership in key positions, and most government institutions fall short of that mark.” |

Finding 2

The Pool of Talented S&T Candidates for Presidential Appointments Is Less Broad and Deep Than It Should Be.

The pool of qualified candidates for S&T presidential appointments is insufficiently broad (representation from industry is low) and deep (some qualified candidates do not agree to enter the pool).

In the panel's collective experience, many prospective candidates refuse even to be considered for government posts. No records are kept of how many people have declined a nomination or withdrawn early for such reasons. However, we can analyze the origin of appointees just before nomination as a surrogate measure.

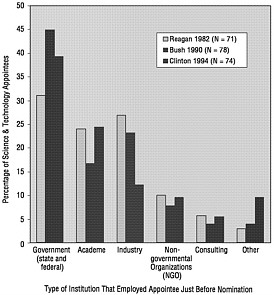

Appointments from industry: From their personal experience, the members of the panel were concerned about the number of appointments from industry in recent years. To test its impression, the panel identified the persons who held S &T appointments in the second years of the Reagan, Bush, and Clinton administrations and then ascertained the position that each of these appointees had held immediately before entering government service. The results of the analysis are shown in Figure A-1 and Table A-1 .

As shown here, the percentage of S&T appointees who came from industry declined from 25% the Reagan-Bush years to 12% in the Clinton years. This decline is statistically significant. Of particular concern is the low representation of people with managerial experience from the pharmaceutical, chemical, and information-technology indus

Figure A-1. Science and technology appointees in the second year of the Reagan, Bush, and Clinton administrations, by institutional background. Source: Data collected by the National Academies' Panel on Ensuring the Best Science and Technology Presidential Appointments.

tries. Recruitment of leaders in emerging fields (biotechnology and information technology) is especially difficult.

Table A-2 from the Obstacle Course report shows the compliance actions that presidential appointees had to undertake.

The quality of appointees: It is difficult, if not impossible, to measure the quality or effectiveness of presidential S&T appointees. On the basis of their particular experiences, the members of our panel felt that it was generally high. In the Brookings survey of all PAS appointees, the picture is less positive. When respondents were asked to comment on the quality of their colleagues, some (11%) gave high marks and only a few (8%) were disappointed. The vast majority felt that they were a “mixed lot”, including some who were of high quality and some who were not. The percentage of those expressing reservations about their colleagues rose from 78% in 1984 to 87% in 1999.

The attractiveness of government service to scientists and engineers is often diminished by both professional losses (the need to interrupt research, an irreversible career shift toward management, time away from a fast-moving field) and financial losses (unduly complex and restrictive preemployment and postemployment requirements).

For members of some professions, such as the law and economics, a tour of government service offers career advantages, including an expanded circle of professional contacts. For most S&T leaders, however, the decision to go into government for a few years often means an interruption of a research career, removal from the cutting edge of one's field, and perhaps a career shift toward management and away from bench research and teaching. Thus some S&T leaders are naturally resistant to recruitment efforts, especially if they are not couched in terms that indicate good understanding of the importance of S&T policy. A White House staff must understand the importance of

Table A-1. Science and technology appointees in the second year of the Reagan, Bush and Clinton administrations by background. †

|

Clinton 1994 |

Bush 1990 |

Reagan 1982 |

||||

|

N |

% of total |

N |

% of total |

N |

% of total |

|

|

Government (state and federal) |

28 |

38% |

35 |

45% |

22 |

31% |

|

Academe |

18 |

25% |

13 |

17% |

17 |

24% |

|

Industry |

9 |

12% |

18 |

23% |

19 |

27% |

|

Non-governmental organizations |

7 |

10% |

6 |

8% |

7 |

10% |

|

Consulting |

4 |

5% |

3 |

4% |

4 |

6% |

|

Other |

7 |

10% |

3 |

4% |

2 |

3% |

|

TOTAL * |

73 |

78 |

71 |

|||

|

* Total numbers are not consistent across administrations because of vacancies and changes in positions. S&T positions in the Carter Administration were too different to include. Some positions today did not exist during the Carter administration as Cabinet departments were created during that period. |

||||||

Table A-2. Compliance actions required of presidential appointees serving June 1979-December 1984.

|

Compliance Action |

Percentage of Appointees |

|

No action required |

32.8 |

|

Created blind rust |

11.6 |

|

Created diversified trust |

1.5 |

|

Sold stock or other assets |

32.3 |

|

Resigned positions in corporations or other organizations |

40.9 |

|

Executed recusal statement |

16.7 |

|

Source: Data collected by the National Academies' Panel on Ensuring the Best Science and Technology Presidential Appointments. |

|

recruiting qualified talent for positions that require scientific and technical judgment. 7

|

†Background is defined as the position held by the appointee immediately before government appointment. |

Source: Analysis of National Academy of Public Administration Survey database,1985, as presented in Obstacle Course: The Report of the Twentieth CenturyFund Task Force on the Presidential Appointment Process. The Twentieth Century Fund. 19%, p.60.

For those scientists and engineers who are willing to consider presidential appointments, a key barrier to the willingness of these people to take the next step are the unduly complex and restrictive preemployment and postemployment requirements. These are described in more depth in the following sections.

Preemployment requirements: The need for reasonable regulations to promote ethical conduct in government is clear, and most ethics laws, especially those requiring public financial disclosure and prohibiting federal employees from participating in matters in which they have a financial interest, are necessary. But recent efforts to achieve a scandal-proof government can deter talented and experienced S&T personnel from taking senior government positions.

The financial consequences of accepting a presidential nomination or appointment can be severe, in particular for senior people in the S&T communities. That is because many senior people in these career fields often accept stock in private firms—especially small technology companies—as compensation. Such stocks are often not publicly traded and thus afford no ready outlet at a market price for sale of an individual's shares. In addition, much of the value of such stock depends on long-term growth of the company after substantial investment in research and development. Depending on the stage of the company's growth, forced divestiture at an arbitrary time can mean selling the stock before its value has appreciated.

Similar situations occur when people have been compensated with stock options in a company and are required to divest themselves of all interests in that company. In some instances, the option has not vested yet and cannot be sold. In others, a substantial downturn in the market value of a particular sector (such as the slump in defense-industry stocks in the early 1990s) can mean that the value of a stock is lower than the option's exercise price at the time a person is required to divest. This difficulty cannot be readily solved by a blind trust, which requires the sale of all assets placed into the trust. Nor can a company ordinarily advance the vesting schedule in favor of an employee; such an action could be tantamount to paying the employee to go into the government and thus constitute a violation of the criminal code.

Congress recently attempted to mitigate losses by those who are forced to divest themselves of stock by allowing them to “roll over” the value of such stock into an acceptable diversified fund. But that is only a partial solution. It is true that the person is not forced to recognize the capital gains on the stock until after the sale of the fund, thus deferring capital gains as though there had been no sale at that time. That does nothing, however, to alleviate the adverse impact on those forced to liquidate stock or stock options at inopportune times, those who do not have a ready market for their stock, or those whose options have not vested. Although the Office of Government Ethics regulations implementing this statute give employees a reasonable time in which to divest, that period may not exceed 90 days, which can be insufficient.

Nominees are also forced to divest themselves of any financial interest in companies that might have business before their agency as a result of interpretations of 18 U.S.C. 208. That law requires that government employees refrain from personal and substantial participation (even through supervision of a subordinate) in any matter in which they, their spouse, minor children, partners, or prospective employers have a direct and predictable financial interest. To impute a child 's, spouse's, or partner's interests to a person is to cast a broad net of financial interests. Agencies have authority to exempt individuals from this criminal prohibition, but in practice they have done so only in instances where the financial interest is deemed de minimis because the holdings are in a diversified fund or regulated investment company and the impact of any actions on the person's actual holdings is remote or inconsequential.

In addition, although the agency might be willing to waive the requirements, a Senate committee may still require the person to sell the offending stock before the agency even has an opportunity to consider the waiver. Many Congressional committees have taken the position that it would be impossible for people to do their job, if they have to refrain from making decisions regarding the companies in which they might have a financial interest. Thus, nominees are required to divest themselves of their stock or any other financial interest in order to secure an appointment. Often, it is this strict approach by the oversight committees that causes disparate treatment of presidential appointees, rather than differing interpretation of the statutes or regulations.

|

7 |

Trattner, John H. 1992. The Prune Book: The 60 Toughest Science and Technology Jobs in Washington. Lanham, Md.: Madison Books. www.excelgov.org/publication/prune97/prune97.htm. |

In an effort to mitigate the effect of the prohibition on holding stocks in companies that might do business with a nominee's agency, the statutes and regulations authorize the use of two types of financial vehicles that avoid the appearance of conflict of interest: qualified blind trusts and qualified diversified trusts. A qualified blind trust is one in which the investor has no knowledge of the assets. A qualified diversified trust is one that the Office of Government Ethics has judged to hold a widely diversified portfolio of readily marketable securities and to be free initially of securities of any entities having substantial activities in which the nominee has an interest.

With respect to using both types of trusts, the forced sale of existing financial holdings that do not meet the criteria outlined above and reinvesting in one of the authorized trusts at what could be an inopportune time can still pose a problem. Because a blind trust is considered blind only with regard to trust assets about which a person has no knowledge (see section 2634.403, Code of Federal Regulations), nominees desiring to put their holdings in a blind trust must first sell all their current assets. In addition, any legal or other fees required to establish the trust must be born by the nominee.

Postemployment restrictions: In its 1992 study of this issue, 8 COSEPUP's panel reported that presidential recruiters, as well as scientists and engineers who have been approached by recruiters, found that the laws restricting postgovernment employment have become the biggest disincentive to public service. Overlapping, confusing, and in some respects over broad measures that were suspended with the passage of the 1989 Ethics Reform Act have come back into effect, and there is constant pressure to broaden the restrictions further by banning officials involved in specific procurement actions from working in any capacity for any competing contractors for periods of 1, 2, or 3 years.

Confusion often results from the wording of Sec. 207 of the Ethics in Government Act: a government employee's postemployment options may be judged by the degree of involvement in an agency's specific contracting actions. For example, a former government appointee might be barred from employment with a company with which that person had “personal and substantial” responsibilities for dealing while in government or with a company whose activities were “under his/her responsibility”. These relationships can be difficult to determine, and their interpretation can vary among employers or attorneys.

The degree of involvement also governs the period, after government, during which a former employee must not “communicate [with his or her former agency] with intent to influence” various actions. That might not bar a person from employment itself, but it bars such communications. Some people can avoid this difficulty in their post-government employment, and some cannot—it depends on the type of job one had in the government, the nature and extent of involvement with contracting, and the nature of the postgovernment job.

In particular, a person is banned forever from making any communication or appearance before the government with the intent to exert influence on behalf of another person with regard to any particular matter involving a specific party in which he or she participated personally and substantially as a government employee. One is prohibited for 2 years from communicating or appearing before the government on any particular matter involving a specific party that was pending under one's responsibility. Senior officials are also prohibited for 1 year from appearing before or communicating, on behalf of another, with their former agency.

The basic features of those restrictions are statutory and afford little flexibility. In addition, President Clinton, by executive order on his first day in office, increased the “cooling-off period ” during which one cannot communicate with one's former agency from 1 year to 5 years for particular senior employees. For a scientist or engineer, that can mean the inability to seek a research grant from an agency even if that agency had been a primary source of support before government service. (In this case, however, the scientific community is assisted by the exception allowed for persons representing degree-granting institutions of higher learning. In addition, an agency is allowed to make an exception for communications furnishing scientific or technological knowledge.) Finally, the 1-year ban prohibiting lobbying a person's agency was extended to 5 years by the Clinton Administration for all appointees paid at a rate of ES-5 or above.

There are additional limitations on procurement personnel in the Department of Defense, but their application to senior appointees is fairly narrow. To be subject to them, an appointee would have to have been the government's primary representative in the negotiation or settlement of a claim in excess of $10 million or personally and substantially participated in a decision-making capacity through direct contact with a contractor. The latter would be highly unusual for any person at the senior level.

Variations in preemployment and postemployment requirements among agencies, departments, and congressional committees create an environment of uncertainty and inequity for appointees.

Standards of ethical conduct are specified for all employees of the federal government by the Ethics Reform Act of 1989. In theory, this uniform set of standards applies equally to all employees, including presidential appointees. In practice, however, there are many variations among the agencies and departments that employ the appointees and

|

8 |

Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy. 1992. Science and Technology Leadership in American Government: Ensuring the Best Presidential Appointments. Washington, DC.: National Academy Press. |

the Senate committees that approve them.

Such variations (and their interpretations) are extensive and constitute a source of uncertainty and sometimes inequity for those considering nominations to PAS positions. For example, agencies, departments, and Senate committees may issue or impose their own supplemental standards of ethical conduct, which are initially unknown to the nominee.

Appointees with the power to award or approve contracts with private firms can encounter variations that are both specific and complex. For example, appointees to the Department of Defense (DOD) are subjected to supplemental rules that can have a tremendous impact on the financial interests of some appointees by requiring divestitures that are not limited to companies in the appointees' direct purview. So, for example, the Director of Defense Research and Engineering is typically required to shed any holding in any company that does business with the DOD —not just those likely to have research and development contracts. This encompasses a large universe of companies when one includes all the firms that sell through the commissaries, all the utility companies that DOD buys power from, and so on.

In addition, one may be required to divest oneself of holdings that are so common among Americans as to be customary, such as those found in virtually all diversified mutual funds. For example, employees of the Environmental Protection Agency who work in or with the Office of Mobile Sources are prohibited from holding stock in any automobile manufacturer (such as General Motors). Similarly, employees who work in or with the Office of Pesticide Programs are prohibited from holding stock in any company that manufactures pesticide products (such as Monsanto).

Senate committees have their own standards for judging ethical conduct. Each committee receives its initial information on nominees from the Office of Government Ethics. It may then ask for additional information with regard to candidates, their spouses, and their children and ask for remedies of any conflicts or potential conflicts it perceives. These remedial measures include recusal agreements, divestitures, resignations, waivers, and qualified trusts.

Additional details about supplementary requirements can be found at the Web site of the Office of Government Ethics: http://www.usoge.gov/usoge006.html#supplemental.

The executive and legislative branches share the responsibility of reducing the preemployment and postemployment restrictions and requirements, which serve as obstacles to public service for S&T leaders.

As is apparent from the description above, both the executive and legislative branches are the source of preemployment and postemployment restrictions. A full list is provided at the OGE Web site, but some specific examples are:

Executive Orders

Executive Order 12674 of April 12, 1989. Principles of Ethical Conduct for Government Officers and Employees.

Executive Order 12731 of October 17, 1990. Principles of Ethical Conduct forGovernment Officers and Employees.

Executive Order 12834 of January 20, 1993. Ethics Commitments by Executive Branch Appointees.

Legislation

Ethics in Government Act of 1978, Pub.L. 95-521, 92 Stat. 1824-1867.

Ethics Reform Act of 1989, Pub. L 101-194, 202, 103 Stat. 1716, at 1724.

Statutes

18 U.S.C. § 207. Restrictions On Formers Officers, Employees, and Elected Officials of The Executive And Legislative Branches.

18 U.S.C. § 208. Acts Affecting A Personal Financial Interest.

Regulations

5 C.F.R. Part 2634. Executive Branch Financial Disclosures, Qualified Trusts, and Certificates of Divestiture.

5 C.F.R. Part 2635. Standards of Ethical Conduct for Employees of the Executive Branch.

Therefore, action is needed by both the executive and legislative branches for changes to occur.

Finding 3

The Appointment Process Is Slow, Duplicative, and Unpredictable.

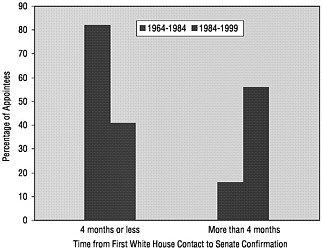

From 1964 to 1984, almost 90% of presidential appointments were completed within 4 months (from the time of first White House contact to Senate confirmation); from 1984 to 1999, only 45% were completed in 4 months.

The period from the point when the President first notices a candidate of the intent to nominate to final approval by the Senate has lengthened considerably, according to a poll conducted for the Brookings Institution and the Heritage Foundation of all appointees in the last several administrations. As shown in Figure A-2 , from 1964 to 1984, almost 90% of presidendtial appointments were completed in 4 months; from 1984 to 1999, only 45% were completed in 4 months. Among the 1964 to 1984 cohort of appointees, only 5% reported that approval took more than 6 months; nearly one-third (30%) of the 1984-1999 group waited more than 6 months. Similarly, almost half the 1964-1984 respondents said that approval took only 1-2 months, but only 15% of the 1984-1999 respondents were approved this quickly.

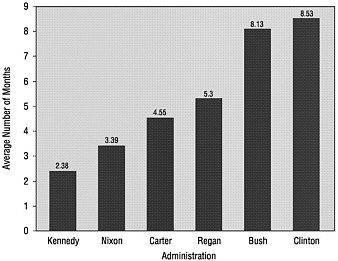

As shown in Figure A-3 , in the most recent administration, the approval process for all new appointees (in all fields) was not completed until an average of 8.5 months after the President's inauguration.

Table A-3 shows that both the mean and median in the time from receipt of the nomination to confirmation by the Senate have more than doubled since the Johnson administration.

Figure A-2. Time for nominees to complete the presidential appointment process, 1964-1984 and 1984-1999.

Note: Time to complete the presidential appointment process is defined in the report below as the time between first White House contact indicating consideration for appointment and Senate confirmation.

Source: The Merit and Reputation of an Administrator: Presidential Appointeeson the Presidential Appointments Process, page 8. The Brookings Institution and The Heritage Foundation,April 28, 2000.

Table A-3. Number of weeks from receipt of nomination to confirmation by the Senate, 1964-1984.

|

Administration |

Mean |

Median |

|

Johnson |

6.8 |

4 |

|

Nixon |

8.5 |

7 |

|

Ford |

11 |

8 |

|

Carter |

11.8 |

10 |

|

Reagan (through 1984) |

14.6 |

14 |

|

Source: MacKenzie, Calvin G., and Robert Shogaan. 1996. Obstacle Course: The Report of the Twentieth Century Fund Task Force on the Presidential Appointment Process. New York: The Twentieth Century Fund Press, p.64. |

||

Where delays occur: Respondents who felt that the process “took longer than necessary” rose from 24% to 39% with regard to Senate confirmation between the 1964-1984 and the 1984-1999 cohorts, from 13% to 34% with regard to filling out financial-disclosure forms, from 24% to 30% for FBI field investigations; from 15% to 27% in other White House reviews of the nomination, and from 6% to 17% in the conflict-of-interest review. These delays did not affect all levels of the appointment process equally. High-level appointees (executive levels I-III, or secretary, deputy secretary, and under secretary) reported fewer frustrations than lower-level appointees (executive level IV, or assistant secretary).

Financial disclosure: Of the 1984-1999 cohort, 41% said that financial-disclosure requirements and conflict-of-interest laws were reasonable measures to protect the public interest. But almost as many (37%) said that the laws as formulated were not very reasonable or go too far. This figure was slightly lower than that for the 1964-1984 group. However, the number who described the process as somewhat or very difficult was twice as high as in the latter group (32% vs. 17%).

Many S&T nominees already have high-level security clearances.

Forms, Required Information, and Background investigations: A common source of delay and frustration, especially for S&T nominees, is the background investigation (BI) by both the White House and FBI. A BI normally contains three elements. First is completion of several sets of detailed questionnaires that require the recording of similar information in different ways. Second, the FBI performs a check of computer records to search for information that might indicate illegal or potentially embarrassing activities. Third is the FBI “full-field investigation”, which involves dozens of interviews conducted by FBI agents with neighbors, business associates, and others. One feature of background checks that many respondents objected to is the duplication of

|

9 |

The financial-disclosure form (SF-278), the Personal Data Statement (White House), the FBI personal- history form (SF-86), and forms required by Senate committees. |

forms and effort. Each party to the approval process has its own extensive form, 9 several require substantially the same information in different formats. Therefore, the nominee is compelled to complete the details of each form separately, often compiling the same information in different ways.

Of respondents to the Brookings survey, four in 10 wanted a more efficient system for collecting information from nominees. Many urged simplification of financial-disclosure and other personal information forms and a standardization in data-collection forms for sharing among departments, agencies, and Senate committees. One source of redundancy is that each Senate committee has its own forms, which often differ from the BI forms of the White House.

One respondent wrote, “I think that you need to have one set of forms that you go through. Basically, the questions which are asked by the White House, by the Senate, and by the agency involved are basically the same questions. But they are all asked in a little different form. So it would certainly streamline the process if you could have an agreed-upon set of questions and inquiries.”

Respondents to the survey were also asked what would make the approval process easier for them. Some 37% of the appointees answered that making the information collection more efficient and the details of the process clearer would make the approval process easier for them; 28% said that the approval process would be easier if the process were faster; and 11% said that it would be easier if it were less partisan and less confrontational. A conclusion mentioned earlier bears repeating: that the availability of more information improves nominees' impression of the process, reducing both embarrassment and confusion.

Figure A-3. Average number of months from inauguration to confirmation for initial PAS appointees, by administration.

Source: Mackenzie,Calvin G., and Robert Shogan. 1996. Obstacle Course: The Report of the Twentieth Century Fund Task Force on the Presidential Appointments Process. New York: Twentieth Century Fund Press, p. 72.

Nominees also believe that the clearance process could be streamlined. For example, many S&T nominees already have high-level security clearances. One respondent to the Brookings/Heritage survey made the following comment: “One dimension which I find really bizarre is the special security clearances. I came to the offer with a lot of security clearances already granted me, including access to very sensitive material. I did not believe it was necessary to go over the whole thing again —as if I were a total unknown to the system. That . . . took a large amount of time and I don't think it was done very well.”

From the information available, COSEPUP has concluded that the presidential appointment process is both complex and burdensome and is likely to dissuade some of the most qualified and desirable candidates from seeking or accepting presidential appointments. In the words of G. Calvin Mackenzie, a distinguished scholar of the appointments process who directed the Twentieth Century Fund's task force:

Securing a Presidential appointment is a long and winding road. . . . Many such people now have no interest in being Presidential appointees, even if the opportunity presents itself. They have no wish to have every aspect of their personal and professional lives scraped over by the President's enemies. They only want to serve their country. But the price of that service has become too high.

The White House nominee-tracking system is slow and inconsistent. Candidates do not receive timely status reports.

White House tracking procedures often fail to provide timely reports to candidates on the status of their appointment. As one recent nominee reported: “I assumed that this was going to be a reasonably expeditious process. . . . Had I known that I was going to be a ship adrift in the sea, I probably would have taken more personal initiative to ensure that the matter was being pushed along.” 10

Among the questions asked of former presidential appointees in the Brookings Institution survey, 11 many had to do with was how nominees are informed and assisted by White House personnel and with the quality of that experience. A number of responses identify features of the experience that would discourage S&T leaders from accepting the invitation to government service and that thereby could limit the pool of potential candidates.

Insufficient information: A total of 39% of respondents said that they had not enough information from the White House or no infor-

|

10 |

Light, Paul C., and Virginia L. Thompson, 2000. The Merit and Reputation of an Administration: Presidential Appointees on the Appointments Process. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution and the Heritage Foundation. www.appointee.brookings.org/survey.htm |

|

11 |

Light, Paul C., and Virginia L. Thompson, 2000. |

mation at all about the rules and obligations of service. Over 30% had to pay $1,000 or more for outside legal and financial advice; about half of those spent more than $6,000.

An unduly complex approval process: One-fourth (23%) called it “embarrassing”, and two-fifths (40%) said it was confusing. The number finding it “embarrassing” rose between 1984 and 1999 from 14% to 25%. The perceived quality of the approval process correlated positively with the amount of information nominees were given early in the process. For example, appointees who said they did not have enough information were more likely to describe the process as an embarrassment (31%) or a necessary evil (57%) than those who were well briefed (embarrassing, 17%; necessary evil, 29%). Similarly, well-informed appointees (80%) were more likely than their less-informed colleagues (59%) to say that the process was fair.

Presidential personnel: The first and continuing point of contact for most nominees is the Office of Presidential Personnel, which handles all paperwork. This office received mixed grades from appointees. When asked to grade the office's helpfulness in a variety of issues, from competence to staying in touch, half or fewer awarded the grade of A or B. Half gave high grades for competence (50% gave As or Bs) and personally caring whether the appointee was confirmed (46%); half gave Cs (21%) or lower (30%) for staying in touch during the relationship.

To widen the pool of potential candidates, a successful recruitment process must be rigorous enough to ensure that individual nominees are fit for their jobs. At the same time, it must give nominees enough information to act in their own best interest throughout the process, move fast enough to bring departments and agencies the leadership they need, and be fair enough to draw talented people into service. Unfortunately, the process today falls short in a number of respects. As indicated by Professor Mackenzie,

Too many good people now decline Presidential appointments when they are offered, and, according to reports of recent Presidential personnel aides, recruiting difficulties seem to be growing. . . . The federal management system relies heavily on lateral entry at the top. When the most talented people refuse to enter because they find the prospect of public service and the process of entry so unappealing, the quality of government performance is in jeopardy. 12

A year later, in a followup paper, Professor Mackenzie updated that, in the wake of its 1996 report, “all the reform proposals have stalled. ” The paper concluded that “the appointment process is too slow and too procedurally complex. ”

|

12 |

Mackenzie, Calvin, 1998. Starting Over: The Presidential Appointment Process in 1997. New York: The Twentieth Century Fund . |