Page 145

8

Historical Background and Evaluation of Marine Protected Areas in the United States

~ enlarge ~

INTERNATIONAL HISTORY OF MARINE PROTECTED AREAS

The concept of protecting marine areas from fishing and other human activities is not new. In the nonmarket economies of island nations in Oceania (Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia), measures to regulate and manage fisheries have been in use for centuries. These include the closing of fishing or crabbing areas, sometimes for ritual reasons but also for conservation when the ruler decided an area had been overfished or needed protection because it served as a breeding ground for fish that would supply the surrounding reefs (Johannes, 1978). In the broader, global context of conventional fisheries management, Beverton and Holt (1957) provided the first formal description of the use of closed areas in fisheries management. This work was in part inspired by the increase in fish stocks observed in the North Sea after World War II when the fishing grounds were inaccessible because of the presence of mine fields. Since then, fishery managers have used closed areas to allow recovery of overfished stocks, to shelter young fish in nursery grounds, to protect spawning and migrating fish in vulnerable habitats, and to deny access to areas where fish or shellfish are contaminated by pollutants or toxins (Rounsefell, 1975; Iverson, 1996).

During the 1950s and early 1960s, as marine ecosystems became more heavily exploited by fishing and affected by other human activities, the need to devise methods to manage and protect marine environments and resources became more apparent. Over the last 20 years, many ocean areas served as de facto reserves

Page 146

because they were too inaccessible (e.g., too deep, too remote, seabed too rocky), but modern technologies have reduced the amount of unfished area (Bohnsack, 1990; Merret and Haedrich, 1997). To develop a practical response to the need for protecting coastal and marine waters, the international community had to resolve issues of governance of marine areas. Beginning in 1958, the Law of the Sea provided a legal framework to address sovereignty and jurisdictional rights of nations to the seabed beyond the customary 3-mile territorial sea. Four conventions were adopted, the Convention on the Continental Shelf, the Convention on the High Seas, the Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone, and the Convention on Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seas.1 This history is summarized in Table 8-1.

These early conventions were followed by other activities that address marine environmental issues, including the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat (1971, known as the Ramsar Convention (http://www.ramsar.org/index.html), and the Convention for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972), known as the World Heritage Convention (http://www.unesco.org/who/world_he.htm). In 1972, the Governing Council of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) reviewed the international situation with respect to emerging environmental problems of wide international significance and created the Regional Seas Programme. Action plans were developed with a particular emphasis on protecting living marine resources from pollution and overexploitation through 13 conventions or action plans (http://www.unep.ch), and the first convention entered into force in 1978 for the Mediterranean Sea. In 1983, another regional seas cooperative arrangement, the Caribbean Environment Programme, adopted the Protocol on Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife of the Wider Caribbean Region (SPAW). This protocol calls for a regional network of protected areas in the wider Caribbean to maintain and restore ecosystems and ecological processes essential to their functioning. Specific components of the Caribbean ecosystem are targeted for protection, including coral reefs, mangrove forests, and seagrass beds.

The first conference on marine protected areas was sponsored by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN, now known as the World Conservation Union) in Tokyo in 1975 (IUCN, 1976). The report of that conference called attention to the increasing pressures imposed by man on marine environments and pleaded for the establishment of a well-monitored system of MPAs that were representative of the world's marine ecosystems. Criteria and guidelines for describing and managing marine parks and reserves were outlined and discussed at the Tokyo conference (IUCN, 1976). In 1980, the IUCN, with the World Wildlife Fund and UNEP, published the World Conservation Strategy, which emphasized the importance of marine environments and ecosystems in the overall goal of adopting conservation measures

1 http://fletcher.tufts.edu/multi/marine.html.

Page 147

|

Year or Period |

Activity or Event |

Significance for MPAs |

|

Historical and prehistory |

The closing of fishing or crabbing areas by island communities for conservation for example, because the chief felt the area had been overfished or in order to preserve the area as a breeding ground for fish to supply the surrounding reefs (Johannes, 197 |

Established the concept of protecting areas critical to sustainable harvesting of marine organisms |

|

1950s and 1960s |

Decline in catch or effort ratios in various fisheries around the world |

At the global level, the need to devise methods to manage and protect marine environments and resources became strongly apparent |

|

1958 |

Four conventions, known as the Geneva Conventions on the Law of the Sea were adopted. These were the Convention on the Continental Shelf the Convention on the High Seas, the Convention on Fishing, and the Convention on Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seas |

Established an international framework for protection of living marine resources |

|

1962 |

The First World Conference on National Parks considered the need for protection of coastal and marine areas |

Development of the concept of protecting specific areas and habitats |

|

1971 |

The Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat (known as the Ramsar Convention) was developed |

Provided a specific basis for nations to establish MPAs to protect wetlands |

|

1972 |

Convention for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (known as the World Heritage Convention) was developed |

Provided a regime for protecting marine (and terrestrial) areas of global importance |

|

1972 |

The Governing Council of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) was given the task of ensuring that emerging environmental problems of wide international significance received appropriate and adequate consideration by governments. UNEP established the Regional Seas Programme. The first action plan under that program was adopted for the Mediterranean in 1975. The Caribbean Environment Programme action plan was adopted in 1981, and the Cartegena Convention was adopted in 1983, including the Protocol on Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife of the Wider Caribbean Region |

Provided a framework and information base for considering marine environmental issues regionally. MPAs were one means of addressing some such issues |

Page 148

|

1973-1977 |

Third United Nations Conference of the Law of the Sea |

Provided a legal basis upon which measures for the establishment of MPAs and the conservation of marine resources could be developed for areas beyond territorial seas |

|

1975 |

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN, now the World Conservation Union) conducted a Conference on MPAs in Tokyo |

The conference report called for the establishment of a well-monitored system of MPAs representative of the world's marine ecosystems |

|

1982 |

The IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas organized a series of workshops on the creation and management of marine and coastal protected areas. These were held as part of the Third World Congress on National Parks in Bali, Indonesia |

An important outcome of these workshops was publication by IUCN (1994) of Marine and Coastal Protected Areas: A Guide for Planners and Managers |

|

1983 |

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) organized the First World Biosphere Reserve Congress in Minsk, USSR |

At that meeting it was recognized that an integrated, multiple-use MPA can conform to all of the scientific, administrative, and social principles that define a Biosphere Reserve under the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Programme |

Page 149

|

1984 |

IUCN published Marine and Coastal Protected Areas: A Guide for Planners and Managers |

These guidelines describe approaches for establishing and planning protected areas |

|

1986-1990 |

IUCN's Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas (now World Commission on Protected Areas) created the position of vice chair, (marine), with the function of accelerating the establishment and effective management of a global system of MPAs |

The world's seas were divided into 18 regions based mainly on biogeographic criteria, and by 1990, working groups were established in each region |

|

1987-1988 |

The Fourth World Wilderness Congress passed a resolution that established a policy framework for marine conservation. A similar resolution was passed by the Seventeenth General Assembly of IUCN |

These resolutions adopted a statement of a primary goal, defined “marine protected area,” identified a series of specific objectives to be met in attaining the primary goal, and summarized the conditions necessary for that attainment |

|

1994 |

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) came into force. UNCLOS defines the duties and rights of nations in relation to establishing exclusive economic zones measuring 200 nautical mile from baselines near their coasts. While facilitating the establishment and management of MPAs outside a country's territorial waters, UNCLOS does not allow interference with freedom of navigation of vessels from other countries |

These two international conventions greatly increase both the obligations of nations to create MPAs in the cause of conservation of biological diversity and productivity and their rights to do so. It is notable that the United States has not ratified eith Conference of Parties of the CBD has identified MPAs as an important mechanism for attaining the UNCLOS objectives and intends to address this matter explicitly in the next few years |

|

1995 |

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, the World Bank, and the IUCN published A Global Representative System of Marine Protected Areas (Kelleher et al., 1995) |

This publication divided the world's 18 marine coastal regions into biogeographic zones, listed existing MPAs, and identified priorities for new ones in each region and coastal country |

|

1999 |

IUCN published Guidelines for Marine Protected Areas |

These updated guidelines describe the approaches that have been successful globally in establishing and managing MPAs |

SOURCE: Modified from Kelleher and Kenchington, 1992.

Page 150

to ensure sustainable development (IUCN, 1980). In 1982, the IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas (CNPPA, now the World Commission on Protected Areas [WCPA]) organized a series of workshops at the Third World Congress on National Parks in Indonesia to promote the creation and management of marine and coastal protected areas. This workshop resulted in the publication of Marine and Coastal Protected Areas: A Guide for Planners and Managers (Salm and Clark, 1984).

Other activities that recommended implementation of marine protected areas (MPAs) for marine conservation included the First World Biosphere Reserve Congress (UNESCO, 1984), the Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas (IUCN, 1987), and the report Our Common Future published by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED, 1987). In November 1987, the General Assembly of the United Nations welcomed this report and adopted the Environmental Perspective to the Year 2000 and Beyond (UNEP, 1988).

In response to the growing awareness of problems in marine ecosystems, the World Wilderness Congress and the IUCN passed resolutions that established a policy framework for marine conservation. These resolutions stated the primary goal of marine conservation, defined “marine protected area,” identified a series of specific objectives to be met in attaining the primary goal, and summarized the conditions necessary for that attainment. They formed the framework for the IUCN policy statement on MPAs that appears in Guidelines for Establishing Marine Protected Areas (Kelleher and Kenchington, 1992).

Two international conventions came into force in 1994, which greatly increased both the obligations of nations to create MPAs in the cause of conservation and their rights to do so. They are the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (UN, 1983; UNEP, 1992). Proceedings on UNCLOS commenced in 1972, and it entered into force in 1994. Although the United States has not ratified either convention, there is considerable agreement, at least in principle, with many recommendations of the two conventions, and the components of treaties in force often become customary international law. UNCLOS establishes duties and rights of nations to establish exclusive economic zones (EEZs) extending 200 nautical miles from baselines near their coasts. While facilitating the establishment and management of MPAs outside a country's 3-mile territorial waters, UNCLOS forbids interference with freedom of navigation by vessels from other countries. CBD increases the obligations of signatory nations to protect biodiversity, including biological productivity. MPAs have been identified as an important mechanism to attain the objectives of the CBD.

There has been considerable progress in establishing MPAs over the past three decades. In 1970, there were 118 MPAs in 27 nations. By 1994, the number had expanded tenfold to at least 1,306 MPAs in many nations, with numerous other proposals under consideration (Kelleher et al., 1995). It is clear

Page 151

that the foundations for broader implementation and use of MPAs to conserve biodiversity and to promote ecologically sustainable development have been established, both internationally and in many individual countries.

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS IN THE UNITED STATES

Over the last century in the United States, federal, state, and local governments have established parks, reserves, wildlife refuges, and other areas adjacent to and sometimes including marine waters. In addition, many military reservations restricted for other purposes have served over time as de facto MPAs. Currently, the United States is involved in discussions on possible multinational MPAs with Canada, Mexico, and Russia.

In the 1920s, increased interest in marine sciences led to the establishment of small scientific research reserves. For example, the Friday Harbor Laboratory (Washington State) designated the Marine Biological Preserve in 1923 but had limited authority for enforcement. Since then, the National Park Service has established several parks with marine components, including Everglades National Park (1934), Fort Jefferson National Monument in the Dry Tortugas (1935), and Key Largo Coral Reef Preserve (1960). At the state level, California established the Point Lobos Marine Preserve (1960), Florida dedicated John Pennecamp Coral Reef State Park (1960), Hawaii established the Hanauma Bay-Kealakekua Bay Marine Life Conservation Districts (1967), Massachusetts created the Cape Cod Ocean Sanctuary (1970), and Washington State extended the boundaries of nine state parks to encompass adjacent marine areas. Local city governments established underwater parks, such as the 1970 designations of the La Jolla Underwater Park (San Diego, California) and the Edmonds Underwater Park (Washington State).

The foregoing history captures the character but not the detail of MPA designations in the United States up until 1970. Since then, government programs such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA's) National Marine Sanctuaries Program have extended the number of MPAs. In addition, areas that have fishing restrictions (zoning) with respect to gear, season, bycatch reduction, and other factors also may be considered types of marine protected areas, encompassing considerable portions of the U.S. EEZ.

Relatively few MPAs in place in the United States qualify as marine reserves (NRC, 1999a). National parks presently engaged in reducing or eliminating fisheries (e.g., Glacier Bay National Monument, Channel Islands National Park) are facing significant opposition because fishing traditionally has been permitted within their boundaries. Few of the national marine sanctuaries have policies to curtail or control fishing, although more areas may be designated with restrictions on fishing activities as the sanctuaries develop new general management plans (Davis, 1998).

No overarching legislation, such as the Coastal Zone Management Act

Page 152

(CZMA) of 1972 (P.L. 92-583), exists for MPAs in the United States. A comprehensive review of each of the many types of marine reserves and the legal and institutional frameworks for their management has not been performed nationally, although efforts to inventory MPAs in some areas have been completed (McArdle, 1997 [California]; Murray and Ferguson, 1998; Mills, 1999; Robinson, 1999; [Washington State]) or are under way (Marine Fish Conservation Network and Center for Marine Conservation, 1999). The following sections present a brief review of the major types of MPAs in the United States, with respect to legislated purpose, management, and attainment of goals. Also included are laws that promote protection of marine habitats or that prescribe management conditions for areas surrounding MPAs (Table 8-2).Criteria for Evaluation

Analysis of the current system of MPAs is constrained to a qualitative rather than a quantitative evaluation by the limited availability of data. The following sections evaluate MPAs designated by major federal programs with respect to their intended purposes and authorities. The status of MPAs in the United States is assessed with respect to the four broad goals identified for marine protected areas (Chapter 2): conserving biodiversity and habitat, managing fisheries, providing ecosystem services, and protecting cultural heritage. In addition, there is the national goal of establishing an interconnected network of MPAs that represent the variety of marine ecosystems in the United States. In all cases, MPAs have to be adequately monitored, allow for research, be enforceable, and have significant stakeholder involvement.

Although the United States is comparatively well represented in global surveys of existing and potential areas (Kelleher et al., 1995), there is no comprehensive inventory of MPAs in the United States, and there is little information on or analysis of the goals, authorizing legislation, agency role, designation process, and current regulations. The lack of a systematic inventory is perhaps a telling commentary on the fragmented approach to establishing MPAs in the United States. Existing MPAs have been instituted for many reasons using diverse authorities with varying degrees of administrative support and limited funding for monitoring and enforcement.

At the federal level, NOAA has begun an effort to inventory coastal and marine protected areas in the United States. However, to date, this inventory includes land areas that border on but do not contain marine waters and does not include areas designated under fishery management regulations (see Table 8-2). In addition, there are descriptive or educational overviews of protected areas, for example, national marine sanctuaries (Seaborn, 1996; Earle and Henry, 1999) and national seashores (Wolverton and Wolverton, 1994). State-level inventories are available for a few states—California (McArdle, 1997), Oregon (OOPAC, 1994), and Washington (Murray and Ferguson, 1998; Mills, 1999; Robinson, 1999). Al-

Page 153

|

Number of Sites |

Area (acres) |

U.S. MPAs |

|

U.S. MPAs |

||

|

Federal |

390 |

149,742,686 |

|

State |

736 |

2,535,715 |

|

Nongovernmental organizations |

128 |

213,275 |

|

Federal Sites |

||

|

NOAA |

33 |

11,923,332 |

|

National Marine Sanctuaries b |

12 |

11,502,720 |

|

National Forest Service |

114 |

38,073,257 |

|

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

42 |

60,211,701 |

|

National Park Service |

201 |

39,534,396 |

|

Total |

390 |

149,742,686 |

NOTE: The U.S. federal government manages about 700 million acres of land and sea for the purpose of natural resource protection and use; approximately 20% is in coastal and marine areas, and less than 2% is strictly marine.

b National Marine Sanctuaries fall under the jurisdiction of NOAA. Therefore, these numbers are represented in the overall NOAA totals.

SOURCE: Lani Watson and Roger Griffis, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, personal communication, 2000.

though the state-level reviews are largely descriptive and were not intended to evaluate performance, they provide a foundation for more detailed examinations.

The most imposing barrier to a systematic evaluation of MPA performance in the United States is the shortage of baseline monitoring of physical and biological parameters within MPAs before and after designation. In many cases, the MPAs are too recently established for significant change to be detected. Even where change is observed, it is difficult to discern cause and effect because management actions, environmental variability, and other exogenous and endogenous factors affect outcome (Ticco, 1996; Allison et al., 1998; Rose, 2000). Thus, performance is difficult to evaluate based on output parameters (Williams, 1980) such as statistically significant increases in fish abundance, stock structure, or species composition of assemblages. Instead, input parameters such as level of funding or program activities are often used as metrics of performance, although they do not measure progress toward management goals.

Page 154

Description and Evaluation of Existing MPA Programs

National Parks

Areas within the national park system are designated by Congress for preserving unique or pristine scenic and wildlife resources in the United States. The National Park Service (NPS) administers national (marine) parks, national recreation areas, national monuments, national seashores, and national sand dunes. Managing NPS resources often involves a cooperative relationship with state agencies across park boundaries (Fagergren, 1998) to ensure effective resource protection.

There are 201 national parks administered in coastal areas, 30-40 of which have significant marine areas as a component. These areas are managed under provisions of the National Parks Organic Act 1916 (as amended) (16 U.S.C. 1) to preserve natural features unimpaired for future generations, while providing for public enjoyment (Keiter, 1988). Hence, they do not necessarily provide representation of different ecosystems. NPS has the regulatory authority to provide a high level of protection to conserve park resources, consistent with the establishment of marine reserves. For instance, federal regulations prohibit the take of most wildlife, prohibit commercial fishing except as permitted by statute, and unless otherwise specified, follow state-level recreational fishing regulations. In most coral reef areas, such as Biscayne National Park, NPS has a legislative mandate to allow recreational and commercial fishing and shellfishing. In American Samoa (the National Park of American Samoa), however, only subsistence fishing is permitted and no public recreational fishing is allowed (NPS, 1998).

NPS is under pressure to reduce or eliminate commercial and recreational fishing inside NPS-administered boundaries (Davis, 1998), including Glacier Bay National Park, Everglades National Park, and Channel Islands National Park (Kronman, 1999), particularly in cases where fishing impairs the very resources that NPS is charged to protect. The authority of NPS to establish more restrictive fishing regulations has been upheld in Everglades National Park (Organized Fishermen v. Watt) (Mantell and Metzgar, 1990), but it has been difficult to garner political support for altering established use patterns. In some parks, the designating legislation specifically exempts activities such as fishing, which are increasingly seen as incompatible uses from the standpoint of nature preservation. Also, because NPS often lacks the baseline data needed to demonstrate resource degradation, fishing interests have successfully argued against restrictions on current fishing practices. Preservationists have argued that the NPS mandate to maintain ecosystem integrity is inconsistent with extractive uses of any kind, regardless of whether or not harm can be proved (McClanahan, 1999).

National parks with a marine component support some of the ecosystem services that appertain to their role as MPAs. Also, to the extent authorized,

Page 155

national parks protect the cultural heritage contained therein. Few of the national parks are located to provide an ecologically interconnected set of reserves, but in several cases (Ferguson, 1997), parks cooperate with neighboring national marine sanctuaries to increase their effectiveness. Research in the marine components of the national parks is supported under a variety of NPS-funded and non-park-funded programs but not at the scale required to meet needs. Although NPS maintains its own enforcement capabilities, the parks rely on education rather than fines or prosecution to obtain compliance. Long-term ecological monitoring is almost nonexistent at the relevant social, economic, and ecological scales. Only recently, has NPS started to develop plans to implement large-scale ecosystem monitoring for its natural resource-oriented units. However, there is insufficient funding to accomplish the task.2

The designation process for national parks tends to be a highly political, combining top-down and bottom-up processes. The agency, prompted by local and national interests, performs studies that form the basis for legislative proposals that usually receive public hearings and other forms of involvement. Action to increase the restrictions on historical uses of park areas have been contentious, not only with regard to fishing closures, but also over what constitutes adequate compensation to established fisheries as seen in Glacier Bay (Box 8-1). In contrast, under the lead of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, NPS and other federal and state entities are using an extensive stakeholder planning process for designing and implementing the Dry Tortugas Ecological Reserve, an approach that has defused some of the controversy (see following section). In the National Park of American Samoa, NPS is endeavoring to preserve a pristine tropical ecosystem consistent with Samoan culture (Chadwick, 2000).

National Marine Sanctuaries

Title III of the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act 1972 (16 U.S.C. 1431-1434) allows the Secretary of Commerce, after consultation with other federal agencies and responsible state officials, to designate national marine sanctuaries (NMSs) for the purpose of “preserving or restoring such areas for their conservation, recreational, ecological, or esthetic values.” Sanctuaries also may be designated by Congress. National marine sanctuaries are administered by NOAA's National Ocean Service. The sparse language of the act has been amplified in the development of regulations to include areas of human use value, coordination of management to complement existing regulatory authorities, support of scientific research, enhancement of public awareness and understanding, and facilitation—to the extent practicable—of all public and private uses of the resources not otherwise prohibited (Thorne-Miller and Catena, 1991).

2 www.nps.gov/glba/learn/preserve/projects/index.htm.

Page 156

BOX 8-1Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve: Phasing Out FishingGlacier Bay,a a 3.3-million-acre unit of NPS, is representative of the significance and difficulties of restricting fishing under NPS mandate to preserve natural processes and ecosystems (GBNP, 1998). Glacier Bay's 600,000 acres of marine waters make it the largest marine area under NPS management. Some 53,000 acres of water are designated as wilderness. Commercial fisheries continue in parts of Glacier Bay, even though this has been prohibited since 1966 within the National Park and since 1980 in designated wilderness. Fisheries have been specifically allowed in the preserve since 1980. NPS objectives for Glacier Bay to enhance park resources and values are

Commercial fisheries (salmon trolling, halibut longlining, salmon seining, and crab pot fishing) existed in the area encompassed by the Glacier Bay National Monument established in 1925. Specific regulations were developed for these activities in 1939 by the Bureau of Fisheries and in 1941 and 1959 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Until recently, the general approach has been to allow established uses to continue. NPS's failure to close commercial fishing was challenged several times by user groups beginning in 1990. After publishing a proposed rule to eliminate commer- |

For the most part, offshore oil exploration and production have been the only prohibited activities in the regulations governing most of the national marine sanctuaries, although in some areas such use continues inside and adjacent to the sanctuary.

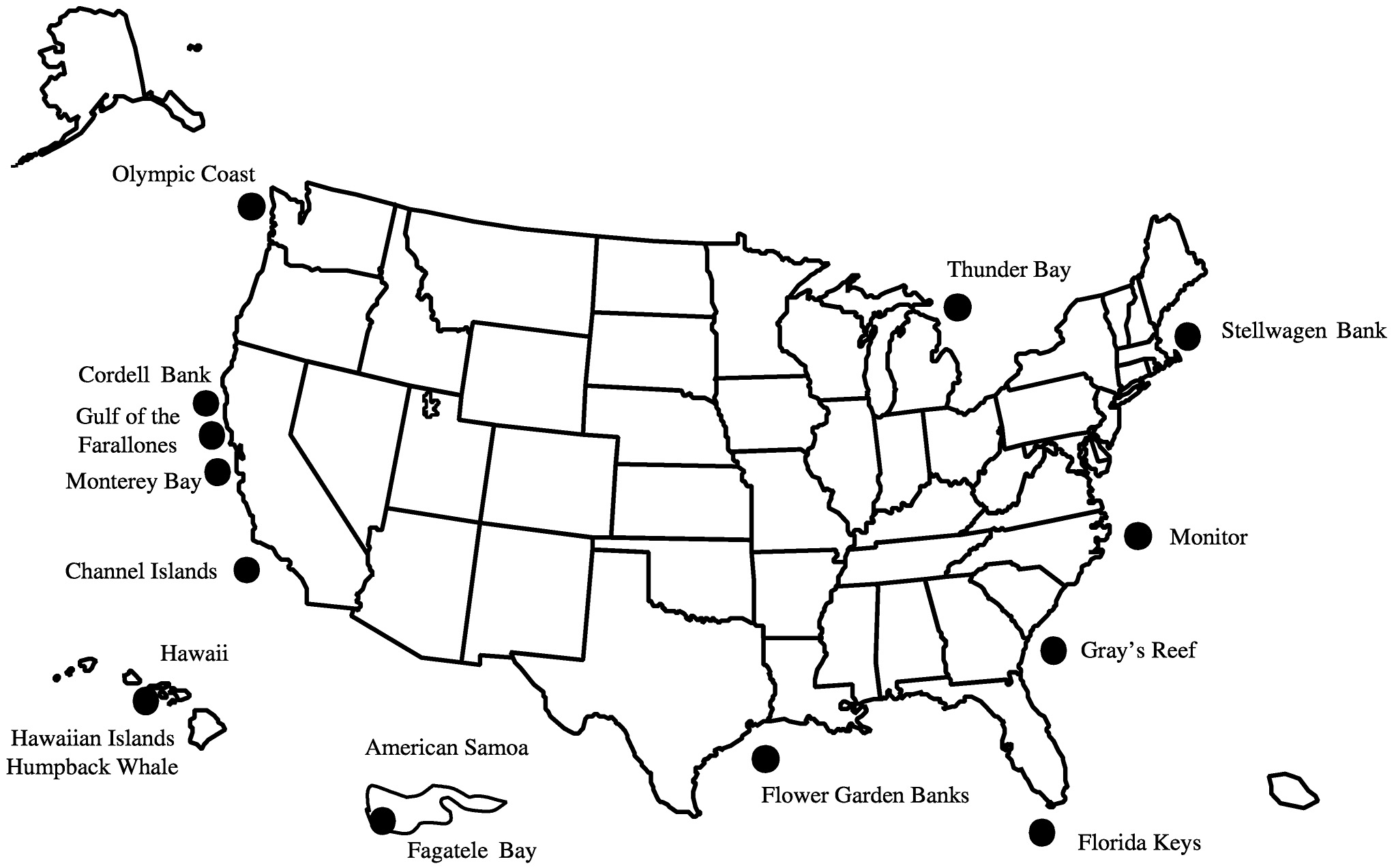

A total of 13 national marine sanctuaries had been designated under this program as of November 2000 (see Figure 8-1). They range in size from Fagatele Bay NMS (American Samoa) (0.25 nmi2) and Monitor NMS (North Carolina) (1 nmi2) to the extensive Olympic Coast (Washington State) (3,310 nmi2) and Monterey Bay sanctuaries (California) (5,328 nmi2) (NOAA, 1997). Despite the name “sanctuary,” they are better characterized as multiple-use resource management areas (Clark, 1998). The average person is surprised to learn that a wide range of consumptive and nonconsumptive uses occurs within

Page 157

|

cial fishing in the park in 1991, the State of Alaska requested that NPS and the Alaskan congressional delegation consider a legislative approach to resolving the issue. No agreement was reached, however. Therefore, NPS proceeded to develop proposed regulations on commercial fishing over a 15-year period within nonwilderness areas of the park. NPS proposal invigorated congressional response and brought legislated modifications in 1998 through the appropriations process (36 CFR part 13). These actions limited the range of NPS actions somewhat but were generally supportive of a phase-out of commercial fishing over the lifetimes of the current participants. With respect to Dungeness crab fisheries, a compensation program was designed to ease the transition for fishermen. It provided an average of $400,000 to each crabber to give up his or her fishery—a total of $8 million. In addition, halibut, Tanner crab, and salmon fishermen with lifetime tenure under the 1998 legislation were allocated $23 million to compensate for not being able to sell their quota shares or limited entry permits (Baker, 2000). Despite more than 10 years of active discussions and policymaking, the disputes are still unresolved. In August 2000, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to adjudicate whether the federal government or the State of Alaska should control the waters of Glacier Bay. In brief, NPS argues that it controls the waters because it was the area manager before Alaska achieved statehood in 1959 and that the underwater territory was not transferred to the state. The state regards the waters as under its jurisdiction. The details of this controversy are fascinating as well as frustrating to observers of efforts to make protection mandates work through the designation of MPAs. They illustrate the complexity of coordinating management objectives, authorities, and realities with respect to competing demands from user groups and changing public values with respect to commercial fisheries in NPS areas. In other areas, the same questions arise with respect to recreational fisheries. a The Glacier Bay is also designated as an International Biosphere Reserve and a World Heritage Site.SOURCE: GBNP, 1998. |

national marine sanctuaries. Frequently, protective measures and management within sanctuary boundaries depend on a cooperative or partnership relationship with resource managers from other jurisdictions (Ferguson, 1996, 1997). A panel of the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA, 2000) recently undertook a review of the National Marine Sanctuaries Program. The panel concluded that sanctuaries should take more steps to protect marine resources within their boundaries, including regulating and prohibiting fishing or other activities when appropriate.

The NMS programs contain a variety of marine environments that constitute neither a representative system of MPAs nor a network. In relation to the objectives and regulatory authority granted to the program, implementation has been successful, with considerable public support for exclusion of oil and gas devel-

Page 159

opment as well as dredging, placement of structures, and dumping (NAPA, 2000). In terms of broader protection mandates, the sanctuary programs facilitate conflict resolution among users (NRC, 1997; Suman, 1997; Suman et al., 1999).

The concept of marine zoning is gaining interest in the form of integrated coastal management (Cicin-Sain and Knecht, 1998; Klee, 1999) in which sanctuaries are a component of the zoning plans at state and national levels. Current development and revisions of sanctuary general management plans incorporate the concept of zoning (Clark, 1998; Salm and Clark, 2000). The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS) is a good example of the use of zoning within such a plan (NOAA SRD, 1996b). In this case, Congress required that zoning be used in the FKNMS to develop management plans for the area, in cooperation with other federal agencies and state and private interests in Florida (Suman, 1997). The Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary used zoning techniques to reduce conflicts among personal watercraft, swimmers, and beach goers. The Channel Islands and Olympic National Marine Sanctuaries employ special area management for shipping, using vessel exclusion zones and specified vessel traffic schemes to reduce the risk of spills and accidents from vessel transportation (NRC, 1997). Currently, zoning is being considered for designating fishing areas and reserves.

With respect to fisheries, many are looking to the NMS program to increase restrictions on fisheries and to implement reserves as part of its mission. This places the sanctuary programs in an awkward position because at the time some sanctuaries were designated, agreements were struck stating that restrictions on fishing in the sanctuaries would not be imposed by federal agencies. Many of the original sanctuary management plans contain this commitment (NAPA, 2000). Sanctuary managers must work with regional fishery management councils and state fisheries officials to respond to specific measures required for managing fisheries. As an example, Channel Islands National Park and Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary are currently engaged in general management planning processes that could lead to various restrictions, including possible “no-take” zones, on recreational and commercial fishing for rockfish and other species.

FKNMS, in a joint effort with the State of Florida, the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council, and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), is proposing a no-take ecological reserve to protect the remote coral reef area of the Dry Tortugas. Studies on the biology and oceanography of the area suggest that this site could serve as a source of larvae of fish, lobsters, and other species for the Florida Keys and the east coast of Florida. Controversy over the original proposal at the time the FKNMS was designated delayed implementation, but recent developments have cleared the way for a collaborative action that satisfies the concerns for coral reef preservation while balancing the economic concerns of commercial fishermen.

Agreement on how to manage the Tortugas was hammered out through a

Page 160

process convened by FKNMS that brought together 25 commercial and recreational fishers, divers, conservationists, scientists, citizens, and representatives of government agencies into a working group charged with using the best available scientific information to evaluate alternative approaches. The working group came up with an ecosystem approach to resolving the problems by focusing on natural resources and not on jurisdictions. Despite previous animosities, this group was able to come to unanimous agreement on a proposal to expand the boundary of the FKNMS by 96 nmi2 and to establish a two-section Tortugas Ecological Reserve totaling 151 nmi2.

This agreement has been incorporated into the FKNMS proposal and is currently awaiting approval from NPS and the State of Florida. The fact that the process was inclusive and focused on the dual interests of providing for coral reef protection and at the same time not unduly affecting other user groups demonstrates that collaborative, consensus-oriented processes provide effective mechanisms for developing viable management options in areas with high levels of conflict (see Chapter 4, Box 4-2).

The NMS program has been successful in increasing the public profile of the sanctuaries and increasing public awareness of the nation's marine resources and conservation needs through effective public outreach and education programs, such as the Sustainable Seas Expeditions. One indication of increasing interest in the NMS program can be inferred from access statistics for the NMS Web site. The number of requests (or hits) per month over a three-month period (May, June, July) was 225,520 in 1999 compared to 573,520 in 2000, representing a 2.5-fold increase. Changing values and rising public expectations concerning the role of “marine sanctuaries” as true protected areas are bringing demands to increase the level of protections in the sanctuaries. This interest has been reflected in an elevation of the program's status within NOAA and a 60% increase in funding for FY 2000. Several sanctuaries are in the process of revising management plans, and research and monitoring programs are being proposed with the hope that funding will be available. In 1999, the NMS budget allocation amounted to about $800 per square mile under its jurisdiction. This compares to $6,167 per square mile of U.S. Forest Service jurisdiction and $16,667 per square mile under NPS jurisdiction. Significantly increased allocations in FY 2000 (about $1,250 per square mile) will help NMS managers improve the coverage of monitoring programs and decrease reliance on volunteer efforts. Because of the lack of effective monitoring in most NMS areas, most measures of sanctuary program success are limited to inputs (budgets and activities) (NOAA SRD, 1996a; NOAA, 1997; NAPA, 2000) rather than outputs (resource evaluations).

National Estuarine Research Reserves

The National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) is a hybrid program administered at the federal level to provide the funding, infrastructure, and coordi-

Page 161

nation for individual reserve sites that are designated and managed at the state level. By 1999, a system of 25 NERRs had been established under Section 315 of the CZMA. This program is administered by the U.S. Department of Commerce, under NOAA's National Ocean Service, with management authority delegated to state and local governments. Because these valuable estuarine habitats fall under the jurisdiction of the states, they require protection by state law ( http://www.ocrm.nos.noaa.gov/nerr/welcome.html).

The primary purpose of the NERR program is to promote and coordinate scientific research, but commercial development of the area is either prohibited or controlled. Although the intent is to protect estuaries for long-term research and education, goals of estuary restoration and recovery also are supported (Thorne-Miller and Catena, 1991). Many different habitat types are included among the NERRs designated to date, but selection has been based more on opportunity than on representation. Monitoring is conducted on a more systematic basis than for most other protected areas but often as a result of scientific monitoring for research purposes or through volunteer activities (T. Stevens, Manager, Padilla Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, personal communication, 1999). Monitoring has been relatively comprehensive and consistent in the areas of water quality and atmospheric conditions. The NERR System-Wide Monitoring Program (SWMP) program has developed monitoring protocols, trained personnel, and purchased and deployed equipment to increase understanding of how environmental factors influence estuarine change and functioning (Wenner and Geist, 2001).

National Wildlife Refuges

Hundreds of coastal and marine national wildlife refuges (NWRs) dot the shores of the United States. NWRs with marine components contain the largest area under current federal designations. The system is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) under a variety of laws. Since the early 1890s, presidential declarations and later congressional mandates have been used to designate NWRs that encompass many kinds of wildlife and habitats in the marine environment. Designation relies heavily on the allocation of parts of federal lands or lands acquired by donation or purchase as habitat for wildlife.

Although they are called refuges, hunting and commercial fishing are approved activities in NWRs, but the FWS can institute suitably restrictive measures if required to conserve wildlife or habitat (Adams, 1993). Refuges play an effective role in protecting threatened and endangered species and preserving habitat for wildlife. In the marine realm, this approach has been applied for migratory birds. Concerted efforts have been made to provide for the needs of waterfowl by obtaining representative habitats for resting and feeding spaced appropriately along the migratory flyways. In addition, the nesting and rearing habitats at the terminus of their migrations are also targeted. In this sense,

Page 162

NWRs come close to meeting the criterion of an interconnected network of reserves for migratory waterfowl (http://www.refuges.fws.gov/NWRSFiles/Legislation/HR1420/TOC.html). In addition, the FWS's role in protecting seabirds brings it into increased contact with fishery managers over endangered species such as marbled murrelets, kittywakes (salmon fisheries on the West Coast), short-tailed albatross, spectacled eider, and Steller's eiger (in the North Pacific). Consultations under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) focus efforts to develop seabird avoidance and monitoring programs by the fishing fleet and fishery managers.

The legislative history for many NWR areas may “grandfather” in patterns of use that may be seen as destructive or inappropriate for the protection mandate implied in the term “refuge,” especially since past practices of management may have been lenient. Refuges usually allow hunting and fishing (recreational and commercial), but there is pressure to modify these practices when damage to resources is demonstrated (Adams, 1993). Public perceptions of refuges are changing such that higher levels of protection are expected, which is pushing management in that direction. There is now a general trend toward more protective management of the NWR System as indicated in the National Wildlife Refuge System Improvement Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-57).

Monitoring and research are a large component of FWS expenditures and personnel activities. Monitoring of wildlife populations, especially wildfowl, takes priority, but “strategic” monitoring of habitat change and other factors affecting wildlife is also undertaken. The reliance of the FWS on field personnel for management and research disperses agency staff over wide areas and into small communities. This has benefits in the form of involvement with stakeholder communities and interests, as well as being able to take enforcement action as necessary when education and deterrence fail.

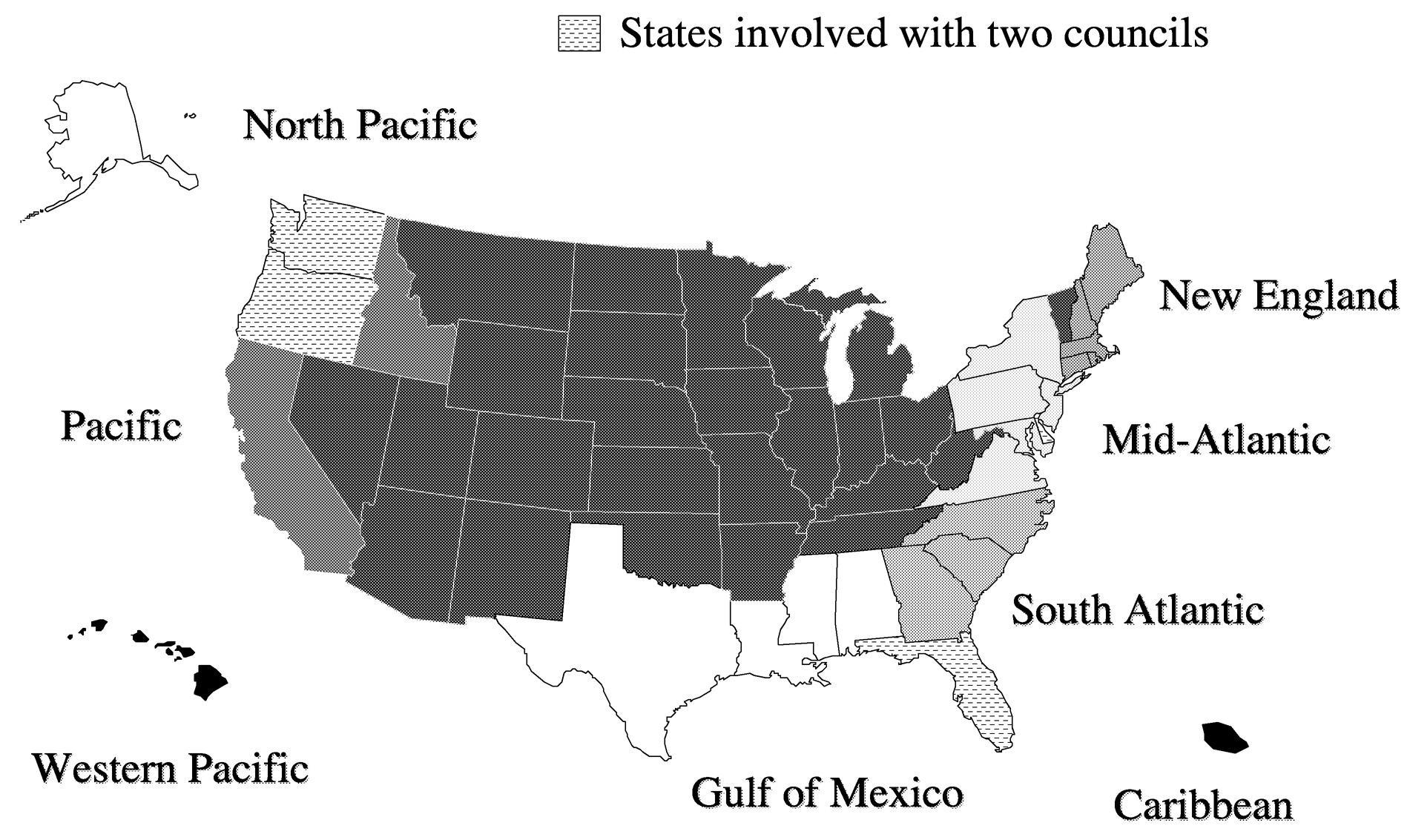

Fishery Management Areas

Fisheries reserves are defined in Chapter 1 as areas that preclude fishing activity on some or all species to protect essential habitat, rebuild stocks (longterm, but not necessarily permanent, closure), provide insurance against overfishing, or enhance fishery yield. Under current federal practice, these designations are made on the recommendation of regional fishery management councils (Figure 8-2) to the Secretary of Commerce in accordance with the MagnusonStevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (NOAA, 1996a), the principal statute guiding regulation of fisheries in federal waters. The eight regional fishery management councils were established under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act in an advisory role to NMFS with the responsibility to develop management plans for the fisheries under their jurisdiction. The National Marine Sanctuary Program must work through the regional fishery management councils and NMFS to implement fishery regulations within a sanctuary (see Figure 8-1).

Page 163

~ enlarge ~

FIGURE 8-2 Map of the eight regional fishery management councils and the states under their jurisdiction. Used with permission of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Page 164

The fishery management council system represents an innovation in fishery management in the United States through its recognition of regional differences and perspectives in the design of management measures. For many years, public apathy about living marine resources and the intense interests of commercial and recreational interests resulted in fishery management council discussions that were limited in scope, often consisting of acrimonious fights among users. Increasingly, as public awareness of fisheries issues has grown, the public voice is heard more often in the council process. In addition, a variety of other interests now broaden the base of council hearings, comment periods, and committee work (e.g., divers, community groups, tribes, consumers). Concerns are increasingly expressed that council decisionmakers are drawn from conventional user groups that are generally unresponsive to other issues. NMFS involvement in planning and stakeholder processes involving other agencies is occurring with more frequency and in innovative ways.

The use of fishery reserves in fishery management is well recognized in practice as well as in the literature (Murray et al., 1999; NMFS, 1999). Zoning decisions made to restrict fishing gear impacts, reduce bycatch, and protect species during vulnerable life stages are common tools employed in fisheries management (NMFS, 1999). Few no-take reserves exist in federal waters, but there are numerous areas in which partial closures are utilized. For example, between the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea, bottom trawl closures are in place for approximately 81,000 nmi2, an area about equal in extent to federal waters fished off New England. While the principal purposes of fishery reserves established in the United States are to reduce fishing mortality, protect critical life-history stages, ensure continued fish production, and reduce secondary impacts of fishing (e.g., Alaska: see Ackley and Witherell, 1999; Witherell et al., 2000; New England; see NOAA, 1999; Gulf of Mexico and Southeast Atlantic; see Coleman et al., 1996), these measures may also directly and indirectly confer benefits in the form of conservation of biodiversity and habitat. In some cases, critical habitat is designated for endangered species (e.g., for monk seals and Steller sea lions) but incidentally provides protection for other species. Fisheries, marine mammals, and endangered species management each offer avenues to create reserves and to better manage resources generally.

The effectiveness of fishery reserves has been discussed earlier in this report (Chapter 5 and Chapter 6), but there are few examples of reserves that specifically test design principles for optimal fishery enhancement. As pointed out in this study and in others, (e.g., NRC, 1999a), such limited measures as presently in place in most if not all fishery management regions are inadequate to maintain or restore marine fisheries. In some areas, fishery reserves may simply reallocate the catch to recreational rather than commercial fisheries, with no evidence that ecosystem function will improve.

Work by NMFS, and the regional fishery management councils to fully implement the habitat provisions of the 1996 amendments to the Magnuson-

Page 165

Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (Sections 303(a)[7] and 305(b)), continues and includes serious examination of fishery reserves as a component of the management approach. Fishery reserves presently are being considered by the Pacific Fishery Management Council to protect rockfish (Sebastes spp.). The South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Councils have a reserve to protect coral habitat known to be important to reef fish. The Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council recently approved two marine reserves to evaluate their effectiveness in protecting grouper populations. Under the essential fish habitat provisions of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, regional fishery management councils must assess habitat needs of all managed species and amend their fishery management plans accordingly to provide protection where required. In addition, councils are to identify habitat areas of particular concern, and these areas must be given special management attention. To reduce effects of fishing gear on the seabed and avoid bycatch, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council requires that all pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) trawling be conducted using midwater trawls. Similarly, the New England Fishery Management Council has closed areas of Georges Bank to bottom trawling and dredging to protect critical habitat for juvenile groundfish (NOAA, 1999).

Because the work on fishery reserves by regional fishery management councils has been driven primarily by single-species concerns and gear conflicts, not by an overall ecosystem-based agenda, these reserves do not constitute an interconnected network. Compliance is generally high and monitoring focuses on stock assessments for the target species. Evaluation of impacts on other components of the ecosystem is neither routine nor at the scale that would allow short-and long-term effects to be detected. In fact, the assessment of fishing effects is generally considered more an area of research than of monitoring. Fully protected reserves would be necessary to provide a baseline against which comparisons can be made with fished areas, in order to distinguish fishing effects from other anthropogenic impacts such as pollution and loss of wetlands (Murray et al., 1999). Fishery managers are optimistic that over the next 5-10 years, declines in fished populations will abate and recoveries of fish stocks will be evident. Others are less sanguine about the pace of change and call for more actions employing the precautionary principle.

Other Federal Areas and Legislation

The U.S. Forest Service (USFS) manages vast areas of public land adjacent to marine waters, primarily in southeast Alaska and California. Its chief legal mandates reside in the Multiple Use Sustained Yield Act 1960, Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act 1974, and Federal Land Policy and Management Act 1976, dealing with managing forests, grazing, water, wildlife, and minerals in terrestrial contexts (Wilkinson and Anderson, 1987; USDA,

Page 166

1993). It does not appear that federal national forest designations provide authority in intertidal or state waters, although management of uplands and watersheds to protect these areas is an important responsibility (Cubbage et al., 1993). Due to the popularity of fjords and bays surrounded by national forest lands in Alaska at sites such as Misty Fjords and Admiralty Island National Monument (www.alaska.net/~anm), recreational boating and other uses are managed. In northern California, national forestlands and their management are important in controlling runoff of silt that can be a problem in nearshore environments. In Big Sur, California, recent coastal conservancy acquisitions are being added adjacent to national forest lands. Given the limited jurisdiction of the USFS has over marine areas, it is not possible to apply the criteria for evaluation set out in this chapter. It may be expected that the role played by the USFS in the use and protection of adjacent marine waters will increase, especially under President Clinton's executive order on MPAs (Appendix E).

Federal management of military reservations that may restrict or regulate access to shoreline and offshore areas creates de facto MPAs that can be significant for scientific research, fish refugia, and habitat preservation. Two examples are Kaneohe Bay Marine Air Force Base (D. Drigot, personal communication, 1999) and the restricted access zone around the Kennedy Space Center in Florida's Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge (Johnson et al., 1999). In both of these areas, increased abundance of fish has been associated with restricted access (D. Drigot, personal communication; Johnson et al., 1999).

Besides direct designation of distinct MPAs such as national parks, sanctuaries, and estuarine reserves, existing legislation permits federal agencies to take actions that include establishing no-take reserves and other protective measures that may be equally or more effective depending on the conflict or opportunity at hand (Table 8-3). Other legislation provides ways to mitigate or minimize threats to designated MPAs by virtue of management measures taken outside MPAs. Under existing legislation and the executive order of 2000, federally funded or conducted activities are prevented from harming many key areas such as critical habitats for endangered species. Full and effective use of existing legislative tools could vastly reduce impacts of human disturbance on the marine environment and complement MPA designations as tools for conserving resources or biodiversity.

The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) (P.L. 92-522) of 1972 authorizes NMFS to take measures to protect marine mammals that may involve setting aside habitat required by various life stages, although the chief provision is the prohibition on “taking” marine mammals directly or indirectly (e.g., through changes in habitat). Similarly, the ESA of 1973 (P.L. 93-205) allows the Secretary of Commerce to identify threatened and endangered species (for most marine fish species, marine mammals, and sea turtles) and to designate habitats critical to their survival. Frequently, combination of the MMPA and the ESA results in designation of critical habitat for species such as Steller sea lion (Eu-

Page 167

|

Laws That Permit Designation of MPAs |

Effect |

|

National Marine Sanctuaries Act. (16 U.S.C. §§ 1431 et seq.) |

Designation of National Marine Sanctuaries for the purpose of comprehensive and coordinated conservation and management while facilitating compatible public and private use of resources not prohibited by other authorities |

|

Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (16 U.S.C. §§ 1801-1883) |

Establishes fishery management authority over living marine resources on the Continental Shelf and in the EEZ. Includes national standards, regional fishery management councils and requirements for fishery management plans; also includes authority to designate open and closed areas as fishery management tools to protect spawning and rearing populations, essential fish habitat, habitat ares of particular concern, etc. |

|

National Park Service Organic Act (16 U.S.C. §§ 1,2-4) |

Creates the National Park Service to administer parks, monuments, and reservations as established by Congress for the purpose of nature preservation and public enjoyment |

|

Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 as amended (CZMA) (16 U.S.C. §§ 1451 et seq. [See also section 6217 of the Coastal Area Management Act Reauthorization Amendments of 1990 (16 U.S.C. §§ 1455b)] |

Establishes the National Estuarine Research Reserve System under which states may seek federal approval for NERRs if the areas qualify as biogeographic and typological representations of estuarine ecosystems that are suitable for long-term research and conservation |

|

National Wildlife Refuge System (16 U.S.C. § 668dd) |

Establishes areas for conservation of fish and wildlife, prohibits damage to such resources, and requires a permit for use. Public recreation is permitted to the extent that it is not inconsistent with the primary objectives for which an area is designate |

|

National Wilderness Preservation System 16 U.S.C. § 1131 |

Congress can designate areas within jurisdictions of land management agencies as part of a system of federal wilderness to be managed so as to preserve its natural conditions |

Page 168

|

Laws that Regulate Activities in the Marine Environment |

Effect |

|

Oil Pollution Act of 1990, (33 U.S.C. §§ 2701 et seq.) |

Improves federal response authority, increases penalties, and requires tank vessel and facility response plans. Defines scope of damages for which there may be liability |

|

Federal Water Pollution Control Act/Clean Water Act, as amended (33 U.S.C. §§ 1251 et seq.) |

Establishes program for restoring and maintaining the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the waters of the United States, including offshore oil and gas. Section 320 establishes the National Estuary Program, which uses a consensus-based approach for protecting and restoring estuarine ecosystems. Prohibits discharge of oil and hazardous substances into coastal and ocean waters. Requires operable marine sanitation devices(Section 312). Regulates discharge of dredged or fill materials in territorial seas(Section 404) |

|

Ocean Dumping Act (Titles I and II of the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act of 1972) (33 U.S.C. §§ 1401 et seq.) |

Requires a permit for transportation and dumping of any material in ocean waters (e.g., sewage sludge, industrial wastes, high-level radioactive waste, and medical wastes). Authorizes research and monitoring on pollution impacts |

|

National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (42 U.S.C. §§ 4321 et seq.) |

Requires preparation of a detailed environmental impact statement for every federal action that identifies the potential impacts of such actions and alternative approaches that would mitigate any impacts |

|

Endangered Species Act of 1973 (16 U.S.C. §§ 1531-1543) |

Protects species of plants or animals listed as threatened or endangered by requiring the designation of critical habitat and development and the implementation of a recovery plan in such a way as to ensure that any federal action is not likely to jeopardize the existence of the species or its habitat. Prohibits the take of any endangered species |

|

Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 (16 U.S.C. §§ 1361-1407) |

Determines management responsibilities for protection of cetaceans and pinnipeds, sea otters, polar bears, walruses and manatees |

Page 169

|

and establishes a moratorium on taking and importing marine mammals and their products except in special circumstances |

|

|

Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Lands Act (43 U.S.C. §§ 1331 et seq.) |

Establishes federal jurisdiction over submerged lands in the OCS and allows leasing of minerals and energy resources, management of exploration and development, protection of the marine and coastal environment, development of improved technologies, and opportunities for state and local participation in policy and planning decisions |

|

Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 (16 U.S.C. §§ 470aa et seq.) |

Protects historic preservation sites from looting and permits the recovery of these items under permit when inside national parks, wildlife refuges, etc. but does not apply to the OCS |

SOURCE: http:www.yoto98.noaa.gov/; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1993.

metopias jubatus) in central and western Alaska. There, NMFS has banned Alaska pollock fishing within 10-20 miles of rookeries and haulout areas and has severely restricted pollock harvests within the critical habitat of Steller's sea lions.

Additional federal legislation that helps to control human impacts on the marine environment (Table 8-3) includes the Clean Water Act (P.L. 95-217) of 1977; Ocean Dumping Act (Title 1 of the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act) of 1972; Coastal Zone Management Act (mentioned earlier re Section 315) of 1972; Coastal Barriers Resources Act (P.L. 97-348) of 1980; Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act (FCWA 48, Stat. 401) of 1934; Marine Plastics Pollution Research and Control Act of 1987; Oil Pollution Act of 1990; Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980 (amended in 1986); National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA, P.L. 91-190) of 1969; and Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA, 67 Stat. 462) of 1953. The Wilderness Act (P.L. 88-577, 16 U.S.C. 1131-1136) is relevant and has potential application in national parks, refuges, and other areas of the marine environment. Because the concept of “marine wilderness” is frequently offered as a type of MPA, it is useful to provide a formal statement of its purpose under the law. The Wilderness Act essentially allows Congress to designate wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” The Wilderness Act allows a number of uses in terrestrial ecosystems that appear incompatible with its basic purpose to “preserve its natural conditions” (e.g., grazing and mining).

Page 170

It also grandfathers in the use of aircraft and motorboats where these uses were preexisting (Keiter, 1988). In terrestrial wilderness areas, nonmechanized recreation is the standard; yet in the marine environment, motorized recreation or access is the norm. However, special legislation may be passed to restrict certain activities, such as the use of jet skis in the Channel Islands. How to define the nature of marine wilderness is a matter of controversy that may take years to resolve.

Obviously, the federal legislative environment in which MPAs are implemented in the United States is complex, with stringent standards for identification and mitigation of environmental impacts, consultative requirements, and pollution prevention and control measures.

State Initiatives

At the state level, the range and number of MPAs are extensive and include NERRs. Recent efforts to catalog MPAs have reported roughly 100 each in the States of Washington and California, including the federal MPAs but not counting proposed sites or intertidal extensions of state parks. Numbers do not tell the whole story. Murray and Ferguson (1998) categorized MPAs into research and educational marine preserves, recreational marine preserves, marine species preserves, marine habitat or nature preserves, and multiple-use protected areas. They found that private entities such as the Nature Conservancy and land trusts, as well as cities and counties, have participated in developing the concept. An innovative approach to no-take fisheries reserves in Washington State is being undertaken by San Juan County with its voluntary bottomfish fish recovery areas (D. Willows, presentation to the National Research Council, September 9, 1999; San Juan County Marine Resources Committee, undated). This communitybased model has been accepted and replicated by the Northwest Straits Commission in six other counties in the region (Murray and Metcalf, 1998). In addition, the Washington Department of Natural Resources (1996) is developing management plans for some of its intertidal and subtidal lands that are linked to upland conservation areas.

In California, McArdle (1997) found that although there were 101 MPAs occupying 18.2% of California's state waters, only a small (0.2%) portion of the MPA area was closed to fishing. California places high priority on its coastal and ocean resources and consequently has developed an extensive planning process to better protect them (California Resources Agency, 1997). In 1999, the California legislature passed the Marine Life Protection Act, which will launch the establishment of a network of MPAs and the designation of no-take reserves (MPA News, 1999).

Hawaii is known for the Hanauma Bay Marine Preserve on Oahu, which attracts 1.5 million visitors per year (Moribe, 1999). Less well known is the West Hawaii Regional Fishery Management Area Bill (Act 306). It caps aquarium-

Page 171

collecting permits off the island of Hawaii, designates at least 30% of West Hawaii as off-limits for collecting reef-dwelling species, designates fishery reserves to overlap with previously designated areas, expands a day-use mooring system, and prohibits use of gillnets in some areas. This combination of measures is intended to resolve long-standing conflicts among various user groups, as well as to develop MPAs to restore marine life over significant areas of the coast.

Summary of Current System

MPAs in the United States today are not the result of a systematic effort to design and implement a system of MPAs to serve the multiple goals described in Chapter 2. Existing MPAs are embedded in a matrix of programs and policies under which various jurisdictions (federal, state, local) use their authorities to manage ocean space, activities, and resources. There are comprehensive management programs under federal law for coastal zones, clean water, fisheries, and offshore oil and gas, frequently requiring state and local involvement. In addition to these broad management measures, marine areas have been designated for national parks, estuarine research reserves, marine sanctuaries, and wild-life refuges, as well as fishery reserves. In most cases, state and local programs parallel the legislative efforts at the federal level. Thus, the existing MPAs have evolved out of myriad efforts to protect areas for various purposes and using different tools.

Frequently, the overlapping jurisdictions of various federal and state agencies have presented obstacles to the implementation and management of MPAs, indicating the need for greater coordination among these agencies. There is no federal agency or authority charged with the oversight of marine protected areas. However, Executive Order 13158 of May 26, 2000, may provide a framework for greater coordination among federal agencies (Appendix E). At the state level, California convened an interagency workgroup that developed new, simpler classifications to coordinate the fragmented system of existing marine managed areas, defined as “named, discrete geographic marine and estuarine areas along the California coast designated using legislative, administrative, or voter initiative processes, and intended to protect, conserve or otherwise manage a variety of resources and their uses,” and recommended a more inclusive and science-based process for designating new areas (California Resources Agency, 2000). In addition, California's Marine Life Protection Act (AB 993) emphasizes using a more coordinated approach to implement MPAs for marine area management.

Conservation of Biodiversity and Habitat

One could argue, that despite the numerous large and small MPAs found around the United States, marine biodiversity continues to decline. Therefore,

Page 172

more reserves with greater protections should be established. The converse argument is unlikely—that MPAs are part of the problem. However, much of the widespread degradation of the marine environment comes from inadequate regulation of land-based activities that affect the marine environment. Agricultural runoff and other nonpoint sources of pollutants to the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem are implicated in generating the large zone of hypoxic bottom water in the northern Gulf of Mexico (Goolsby, 2000). This is the type of complex management issue addressed under the Clean Water Act. Similarly, coastal hardening affects nearshore habitats and transport of sand. These issues fall, in part, under the aegis of the CZMA. MPAs may not be the complete answer, but their expansion is likely to improve land-based efforts to protect marine biodiversity and habitats.

Fishery Management

The discussion of fishery management above covers primarily federal waters. In state and local areas, there are a large number of fishery reserves established for specific purposes. Unfortunately, relatively little is known about the contribution of these reserves to maintaining or rebuilding fisheries. These areas tend to be small in size and very specific with respect to purpose (e.g., herring spawning area, good habitat for large rockfish). Nearshore environments are often key areas for spawning and rearing of juvenile fish, so their proportional significance in the life histories of some species may be quite large. In addition, it appears that a large proportion of these state and local reserves are proximate to shoreside protected areas as well, and this may show potential for managing across the shoreline boundary. Many of these sites are of relatively recent origin relative to the time scale in which one would expect to see changes in fish populations, species composition, and size distributions. It is also fair to say that few of these have received adequate monitoring or research. It appears that there are considerable opportunities, given the uncertainty in fishery management, to use additional fishery reserves as a hedge against management failure and to learn from what works and what does not. Developing stakeholder processes around a mutual interest of parties in restoring fish stocks can be a key element in this regard where resources are inadequate to fully monitor and perform research.

Other Ecosystem Services

Federally established MPAs clearly demonstrate the provision of a wide variety of ecosystem services. They also illustrate the growing demand for other ecosystem services. State and local designation of MPAs can be responsive to an even wider range of such services, especially where the initiative for the designation derives from local grass-roots, "bottom-up" kinds of requests. These

Page 173

could range from a shoreside community asking for protective designations in its own “front yards,” even if they are not necessarily highly ranked sites for fish production or marine biodiversity, to local governments designating “voluntary” zones for fish recovery. As society becomes more aware of the values that it places on the marine environment, the services it provides, and the potential losses due to degradation, it can be expected that managers will be increasingly called upon to protect these services.