3

Examples of Community-Based Health Literacy Programs

The workshop’s second session presented examples of community-based health literacy programs delivered in various settings and a panel discussion on implementing community-based health literacy interventions (see Box 3-1). Marisa New, board member of the Oklahoma Health Equity Network and chair of the Southwest Regional Health Equity Council, and Leslie Gelders, health literacy coordinator at the Oklahoma Department of Libraries, discussed community-based health literacy interventions in Oklahoma and included an example of a program focused on public libraries. Catina O’Leary, president and chief executive officer of Health Literacy Media, described health literacy activities in four communities in Missouri. Ariella Herman, research director at the Johnson & Johnson Health Care Institute and senior lecturer on decisions, operations, and technology management at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Anderson School of Management, reviewed health literacy interventions delivered through Head Start programs. Following the four presentations, Earnestine Willis, Kellner professor in pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin, moderated a discussion with the panelists.

HEALTH LITERACY IN PUBLIC LIBRARIES1

The Oklahoma Health Equity Campaign, which launched in 2008 and enhanced its focus on health literacy in 2011, is a grassroots coalition that aims to address the fact that Oklahoma has consistently been at the bottom of national health rankings, said Marisa New. In 2016, the United Health Foundation ranked Oklahoma as the 46th healthiest state, and the 2014 State of the State Health Report Card showed failing grades in the state’s mortality rate, prevalence of diabetes, consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, and physical activity. The state was also the sixth most obese state in the nation.

From its inception, the coalition has approached health equity from the perspective that there are many social determinants of health, said New, and it has conducted statewide surveys of communities to identify how community resources make an impact on health. The coalition has developed various position statements that highlight how life-enhancing

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Marisa New, board member of the Oklahoma Health Equity Network and chair of the Southwest Regional Health Equity Council, and Leslie Gelders, health literacy coordinator at the Oklahoma Department of Libraries, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

community resources or social determinants, such as food security and public transportation, affect health.

In 2011, steering committee members recognized the value of having a library representative, and Leslie Gelders is now on the organization’s board. In 2012, said New, Oklahoma had its first health literacy summit that it modeled after similar summits held in Florida and Wisconsin. The second summit, held in 2014, was called Health Literacy: A Powerful Tool for Prevention and Partnership, and it featured a dialogue session that helped the organization from a capacity-building perspective.

At a statewide coalition policy day in 2015, a session that focused on health literacy produced two policy recommendations. The first recommendation, New recounted, advocated for state leaders to understand the link between health and literacy and to reinstate funding for adult literacy programs. The other recommendation requested that the state legislature conduct an interim study examining the effects of low health literacy. In 2016, the coalition’s health literacy action team, collaborating with more than two dozen public and private partners, provided evidence-based health literacy interventions such as Teach-Back and Ask Me 3. Nearly 100 individuals engaged in the training and then worked with decision makers from the public and private sectors to craft the Oklahoma Health Literacy Action Plan. The action plan called for the partner organizations to work to strengthen and sustainably support a home and infrastructure for the advancement of health literacy in Oklahoma. It also proposed coordinated statewide efforts to increase and evaluate efforts to address health literacy challenges or improve health literacy of Oklahoma residents. The coalition took advantage of Health Literacy Month in 2016 to share health literacy messages through social media and the Thunderclap social media amplifier, reaching more than 175,000 people.2

Unfortunately, said New, the coalition’s engagement has been limited over the past year because of budget pressures that have limited public resources. The coalition’s steering committee decided to forge ahead as a nonprofit organization and has since engaged with the Southwest Regional Health Equity Network, which serves Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas. In 2015, this network developed a blueprint for enhancing individual and community health, with the objective of launching a health literacy campaign that would align with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Culture of Health framework and the National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy, explained New. The Oklahoma team’s strategy has been to focus on two evidence-based interventions: the Teach-Back method and Ask Me 3 approach.

___________________

2 This exercise was repeated in October 2017; see https://twitter.com/search?q=%23healthliterateok&src=typd (accessed February 9, 2018).

Gelders then spoke about a specific health literacy program that the Oklahoma Department of Libraries started in 2012 after the first Oklahoma health literacy summit. With assistance and urging from Wisconsin Health Literacy, Gelders wrote a grant and received funds to launch this initiative at five pilot sites across the state. Addressing the question of why she focused on community-based health literacy activities in libraries, Gelders cited a 2015 Pew Research study showing that 73 percent of people who visited a public library in America went there looking for answers about their health. Another study by the Institute of Museum and Library Services showed that over a 12-month period, an estimated 28 million people used the public library to seek assistance from a librarian or to use resources and computers in the library to find out about health and wellness issues, including learning about their medical conditions and finding health care providers. “The question was, ‘Why libraries?’ and the answer is because people are already using their public library to find information about their health,” said Gelders.

Libraries, she noted, are trusted community institutions that offer a non-threatening environment for all members of the community and serve as places of lifelong learning. One reason why libraries may be able to play an important role in health literacy efforts is that the computer and Internet services available at public libraries can provide access to reliable health information for people who do not have access to computers or the Internet elsewhere. In fact, said Gelders, 70 percent of rural public libraries are the only providers of free Internet in their communities. A second reason is that librarians are information experts and they offer their services for free. She noted that some public librarians are taking courses to become health information specialists, and some libraries have health-related tools such as blood pressure monitors, accurate scales, and pedometers for patrons to use.

Gelders remarked that since libraries already offer free programming on a number of topics for adults, teens, and children, it would be relatively easy to include health literacy, health, and wellness topics in that programming. Libraries, through their many connections in communities, can help promote health literacy efforts through their networks. Libraries may offer free space for health literacy programs, and they may have access to state or federal funds they can use for health literacy programming, said Gelders. One caveat, she said, is that many librarians do not know what health literacy means, so they may be intimidated by the thought of initiating a health literacy project or becoming a partner in such a project. One of her roles in Oklahoma has been to provide ideas, technical assistance, and support to libraries to address that problem.

With regard to the grant she procured, Gelders explained that each of the five pilot sites was asked to plan a project based on actual community

needs as noted, in part, by their communities’ scores on the State of the State Health Report. Many of the grantees focused their efforts on healthy eating and exercise, accessing and using credible health information, and providing community education through programming. One program in rural Healdton, Oklahoma, for example, was a hands-on project on healthy eating for children. Over the course of a summer-long pickle-making class at the library, the children learned why it was important to eat fruits and vegetables and why they should control their salt and sugar intake. A family and consumer sciences educator led the project, which had the children work in one of the gardens built between the public library and the county health department.

Another project, based in Elk City, Oklahoma, created a virtual Route 66 walk-a-thon, where individuals and teams were challenged to walk the distance between Chicago and Santa Monica, California, and record their virtual journey on a map in the library. Gelders said 60 individuals walked a total of 16,261 miles, and the local newspaper ran articles about the walk-a-thon that included information about the benefits of increased exercise. In a Claremore, Oklahoma, English-as-a-second-language class, learners used a health-related curriculum and real-world health materials as part of their language instruction, while the Moore Public Library offered free weekly Tai Chi classes. In every case, library sites were required to partner with other organizations in their community, as well as with local health departments. All told, more than 43 organizations, including the local councils on aging, dentists and doctors, food pantries, grocery stories, senior centers, and the National Network of Libraries of Medicine, partnered with libraries to promote health and wellness in communities across Oklahoma. The partners, said Gelders, provided instruction, in-kind services, resources, funding, awareness, and a wealth of ideas to help expand the projects locally.

Gelders mentioned that many public libraries get funds from the state library, which is where she works. She offered her assistance to anyone who wants to get state libraries involved in making health literacy a priority activity. She noted that she hoped to award 25–30 health literacy grants, up from the initial 5, to public libraries in Oklahoma. Gelders also noted that there is an educational website for librarians called WebJunction, which contains a section titled Health Happens at Libraries that includes information, webinars, and examples of how libraries can become involved in promoting health and health literacy.3

She ended her presentation with two quotes. The first came from a public librarian, who said, “Good health for the community has been a mission for me. I did not realize how poor our health was until I began looking at

___________________

3 See https://www.webjunction.org for more information (accessed March 21, 2018).

the statistics. It is very important for libraries to address the needs of their communities and it is a great need in Oklahoma.” The second quote came from an English-as-a-second-language student who said, “I lost 34 pounds as a result of my literacy program. Even though I am studying for citizenship and working on English, I like the weekly weighing on the scales in the literacy office. My tutor helps me record my weight and she helps me read information on walking and eating better. I am smiling because I can see the results.”

COVER MISSOURI’S COMMUNITY HEALTH LITERACY PROGRAM4

When communities ask the Cover Missouri Coalition to talk to their residents in a responsive way about health interventions that are meaningful, they rarely ask for health literacy by name, even though much of what they want has all of the components of health literacy, said Catina O’Leary. She noted that she has seen all over the world that what people want is to learn how and where to get information on health and wellness, and without using the words, develop health literacy skills.

For the past 4 years, the Cover Missouri Coalition has been working with O’Leary and her colleagues on health insurance literacy. This effort has three goals: promoting quality health coverage for every Missourian; improving the health insurance literacy of Missourians; and lowering the rate of uninsured Missourians to 5 percent by the end of 2018. With regard to the last goal, O’Leary said there was no chance of meeting it given that Missouri’s elected leadership chose not to expand Medicaid coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Nonetheless, she said, the Cover Missouri Coalition has grown to include some 900 partners, and bimonthly coalition meetings routinely have 200 to 300 navigators, assisters, and other representatives of the partner organizations who ask hard questions stemming from their experience working on the ground in their communities. Health Literacy Media’s role, she explained, has been to educate the partners about the tools of health literacy and to help them think about how they do their work.

For the first 3 years of this effort, O’Leary’s team conducted what she called standard health literacy activities: creating health literate written materials for assisters and navigators, training frontline workers on verbal and written communications, and helping them make the materials they were using more accessible. Then, in year 3, O’Leary and others in the coalition realized that while it was important to continue the work on

___________________

4 This section is based on the presentation by Catina O’Leary, president and chief executive officer of Health Literacy Media, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

awareness and other aspects of the technical assistance that her organization provided to the partners, there were people who either could not afford insurance because they were in the coverage gap or simply refused to buy it for any number of personal reasons. What the coalition decided to do was take a step back from health insurance to focus on general health and wellness in the community. To enable that effort the Missouri Foundation for Health funded a pilot program to support four communities’ knowledge about health and health care in whatever manner those communities wanted that help.

The pilot program, said O’Leary, aims to engage the community around health and health insurance through strategies that lower barriers to health, and in doing so, help people make informed choices for their family’s health. One outcome of this effort might be to get more people to enroll as they come to understand the value of health insurance to their family’s health, but at the least the hope was to help families be healthier. “Our framework was to meet these communities where they are and infuse health literacy,” said O’Leary.

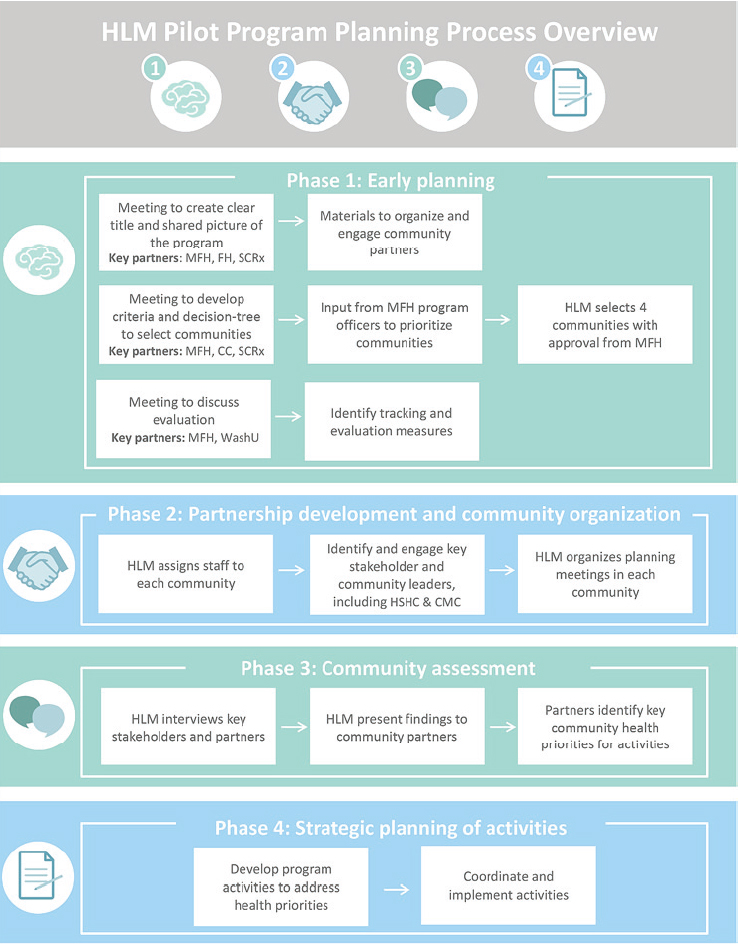

The planning process for working in a community went through four phases (see Figure 3-1). The early planning phase involved selecting the four communities based on a set of criteria and identifying tracking and evaluation measures. In the second phase, two staff members assigned to each of the four communities identified and engaged key stakeholders and gatekeepers and organized a planning meeting with those individuals. In the third phase, staff interviewed the key stakeholders and various community partners to identify community priorities. Phase four involved strategic activity planning that included developing program activities to address community-identified health priorities and to coordinate and implement those activities. The purpose of this complex process, O’Leary explained, was to bring these communities to a place where they wanted health literacy and health education and to provide them with a single contact point who could connect them to whatever resources they needed. For example, if a community wanted media training, one of the staff members assigned to that community would make the necessary arrangements. She noted that the Missouri Foundation for Health provided a mere $5,000 for each community, but that small amount of money forced communities to think hard about what they wanted to accomplish with those funds.

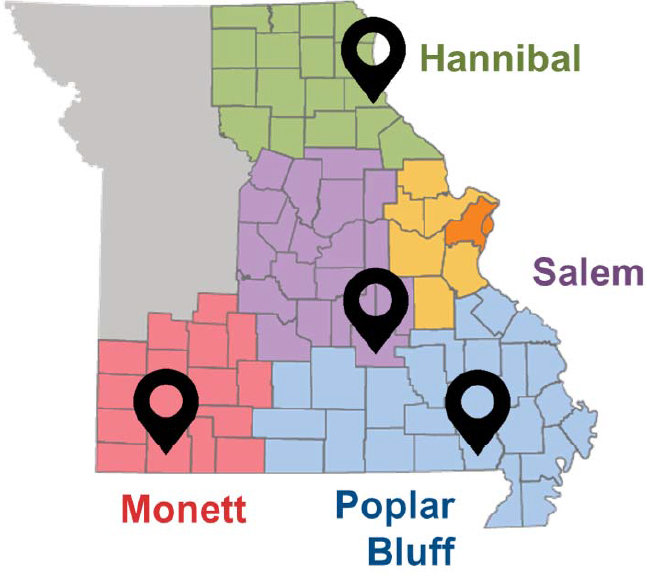

As to how the coalition chose the four pilot communities (see Figure 3-2), it started with the decision to select one community from each of the four Missouri Foundation for Health’s service regions outside of the St. Louis region. They excluded the St. Louis region because of the wealth of resources already in place thanks to the three major universities and other organizations in that region that had their own ongoing activities. In each of the four service areas that were too far from St. Louis to

NOTE: CC = Community Catalyst; CMC = Cover Missouri Coalition; FH = FleishmanHillard; HSHC = Healthy Schools Healthy Communities; MFH = Missouri Foundation for Health; SCRx = StratCommRx; WashU = Washington University in St. Louis.

SOURCE: As presented by Catina O’Leary at the Community-Based Health Literacy Interventions workshop on July 19, 2017.

SOURCE: As presented by Catina O’Leary at the Community-Based Health Literacy Interventions workshop on July 19, 2017.

access those resources easily, the coalition identified communities in which 16 percent or more of the residents were uninsured and 18 percent or more had incomes below the Federal Poverty Level. Two other selection criteria were that the community included Missouri Foundation for Health priority populations and that there were some preexisting relationships with the community. “We did not want to go into communities that had nobody knowing anybody at all because we did not have enough time to start completely cold. We had to at least know one person at one organization who would say yes, please join us,” explained O’Leary.

The final step in the selection process was to ask the communities to take part in the project and have the communities say yes. “We were fortunate that everybody selected us back, but we had to have a lot of meetings to ask a lot of people the question to make sure they selected us back before we started the work,” said O’Leary. The four communities that said yes were Hannibal, Monett, Poplar Bluff, and Salem (see Table 3-1). They are mostly small communities with different levels of minority populations. Monett was of particular interest because it had a large population that did

TABLE 3-1 Demographics of the Four Pilot Communities

| Hannibal | Monett | Poplar Bluff | Salem | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 17,717 | 8,957 | 17,195 | 4,976 |

| Race | 88.8% white 7.1% black 2.4% Hispanic |

74.6% white 0.02% black 23.5% Hispanic |

85.5% white 10.7% black 2.2% Hispanic |

96% white 0.5% black 1.7% Hispanic |

| Education | 82.4% high school diploma or higher | 28% have at least some high school | 78.9% high school diploma or higher | 28% have at least some high school |

| Uninsured rate (for county) | 16% | 22% | 17% | 20% |

| Poverty rate | 22.3% | 28% | 27.7% | 33.3% |

SOURCE: Adapted from a presentation by Catina O’Leary at the Community-Based Health Literacy Interventions workshop on July 19, 2017.

not speak English as its first language, and O’Leary was interested in how their interventions would work differently in such a population.

She noted that all of the communities have been great partners, but the Monett community was perhaps the most excited to be asked. One observation she made was that the Monett community was having difficulty applying for funding from foundations because of structural issues, such as the need for help even applying for a grant. “We have been able to bring some of those issues to light and start conversations about changing processes so communities like this that have a different level of vulnerability are not overlooked,” said O’Leary.

As an aside, O’Leary said that a question people ask her is how she and her colleagues know that the selected communities have issues with health literacy. One answer is that 9 out of 10 Americans have a health literacy problem, but with regard to the selected communities, the answer is that they are comparatively undereducated, have high levels of poverty, and have high rates of uninsured community members.

With regard to what Health Literacy Media and the Cover Missouri Coalition provided to the chosen communities, O’Leary listed the following activities:

- Met with and interviewed partners in each community to hear their opinions on the health of their community;

- Conducted media and awareness efforts to engage the communities around health and health insurance topics, and issued monthly press releases on health topics;

- Convened events and programs to address the health concerns that each community identified, such as health fairs, health screenings, and community exercise programs, in response to specific needs identified by community partners;

- Created and shared resources about health and health insurance, such as print materials, videos, and giveaways to raise awareness;

- Delivered health and health literacy trainings on topics such as health insurance for benefits personnel at small businesses in the community, employees at organizations in the community, and community members; and

- Provided dedicated contacts at Health Literacy Media who share free health resources with community partners.

Both large and small organizations, including health centers, school districts, community centers, and chambers of commerce, were partners in this effort. Healthy Schools Healthy Communities, a separate program supported by the Missouri Foundation for Health, was an important partner in Hannibal because it already had substantial resources in the community. This provided the opportunity to compare outcomes between low-resource and high-resource communities, explained O’Leary.

Discussing the key findings from the pilot programs, she said that community members in Hannibal reported a lack of community awareness about existing health resources even among health professionals, a lack of coordination of health and social services resources, and little knowledge about health insurance and the insurance marketplace. They also noted that health care organizations in Hannibal were using unclear materials, such as discharge instructions, and that there was a significant problem with mental health in the community, particularly among teenagers. One thing O’Leary’s team did was to help the Hannibal community create a resource directory on a smartphone app called Johego to connect the community with the services it needs. At the time of the workshop, Hannibal was planning a community event that would bring together all of the community partners and the local newspapers to launch the app, and O’Leary’s team was preparing to train providers and the public on how to use the app.

Another well-received activity in Hannibal, which responded to the community’s food-related health issues, featured a cooking demonstration by one of the highest ranking female chefs in the U.S. Coast Guard. In addition to addressing a community need, this activity also introduced Hannibal’s children to a non-traditional military path. “We talked about careers, but also provided cooking demonstrations and easy make-ahead

meals,” said O’Leary. “We gave them food and recipes, too, so they could go home and make these dishes.”

O’Leary said that lessons learned during the first year of the Hannibal pilot included the observation that technology can help bridge barriers to creating a unified resource directory, that presentations such as the one by the U.S. Coast Guard chef can add value and exposure to existing programs, and that collaboration among community resources will improve the health of the community. O’Leary noted that the community has already asked for the second year of the pilot to include more information about mental health services, substance abuse, insurance coverage, obesity, and preventive health. The community, she said, is driving an agenda to which she and her colleagues are responding.

The residents of Monett, through a series of meetings with a variety of leaders and community members working in the health and wellness field, identified the issues they wanted the program to address. These included tobacco use, obesity and diabetes, cardiovascular disease, how to motivate the community to be more active, drug use and opioid addiction, and dental and vision services, particularly in the Latino population. One of the activities O’Leary and her colleagues created for Monett was to start a twice-monthly community walk, Monett on the Move, that included 20-, 30-, and 40-minute walks for people of different fitness levels. “We started with 4 people at the first walk, but by the end we were getting 40 people at every walk” O’Leary said.

Other activities involved connecting with the local farmer’s market, setting up a health insurance booth to provide the community with information, and providing health insurance literacy training for the Monett school district and EFCO, one of the region’s major employers. Face-to-face meetings and texting proved to be effective tools for building relationships in the community, and in that respect, proved important to finding social nodes in the community to learn about community norms and culture. Going forward, the pilot plans to target advertising to increase turnout of the Latino and Hmong (people from parts of Southeast Asia) communities for events such as Monett on the Move.

In Poplar Bluff, smoking, obesity, heart disease, drug abuse, and the high poverty rate were the community’s main concerns, as were a lack of access to fresh fruits and vegetables, the struggle to recruit specialty physicians to the area, and a lack of transportation. Poplar Bluff residents were also distrustful of health insurance and the ACA. To address these issues, O’Leary and her colleagues worked with local partners to create a wellness fair that provided health, vision, and dental screenings, as well as health-related giveaways such as Fitbit fitness trackers. They also organized a trail run to raise money for an all-inclusive playground project and provided $20 vouchers to the farmers’ market to every participant. The community

partners, said O’Leary, have said that the issues they want to address in year two of the pilot include building the all-inclusive playground and trail connections and addressing tobacco, heroin, and prescription drug abuse in the community.

The big issues that stakeholders in Salem identified were food insecurity, poor nutrition, lack of physical activity, obesity, overuse of the emergency room for oral health issues, high rates of teenage pregnancy, smoking, heart disease, high rates of poverty, alcohol and drug abuse, lack of transportation, and lack of knowledge about health insurance. O’Leary said that the U.S. Coast Guard chef also made an appearance in Salem. Her demonstrations of how to cook healthy meals on a budget and prepare easy make-ahead meals were well received by the community. So, too, was a 3-day visit by the Smile Mobile, which provided dental services to 7 children and 20 adults and talked about avoiding overuse of the emergency room for dental services. O’Leary noted that this was the first visit to Salem by the Smile Mobile, but now it has a partnership with the Your Community health center. Free cooking classes, she added, proved to be a great benefit for both teenage and adult community members. One lesson learned from this community was that it will be better going forward for a small group of 4–6 community members, rather than a larger group of 15–20 individuals, to decide on the best use for grant funds in year two of the pilot.

One takeaway message for O’Leary was that communities are multilayered, with different gatekeepers for different groups in the community. Another lesson was the need for continuing conversations as projects and relationships evolve. Building sustainable relationships, she noted, takes time and respect. “One of the biggest things I’ve seen across the board is the need for flexibility as a core competency,” said O’Leary. She also noted that the community has to drive the agenda and that the various partners do not always talk about key issues in the same way. “This idea of health literacy is important here,” she said in closing. “We want to teach them our words because maybe those words have some power for them, but we do not have to start in that place.”

HEALTH LITERACY IN HEAD START PROGRAMS5

For the past 27 years, Johnson & Johnson has provided funding to Ariella Herman and her collaborators to bring Head Start directors to the

___________________

5 This section is based on the presentation by Ariella Herman, research director at the Johnson & Johnson Health Care Institute and senior lecturer on decisions, operations, and technology management at the University of California, Los Angeles, Anderson School of Management, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

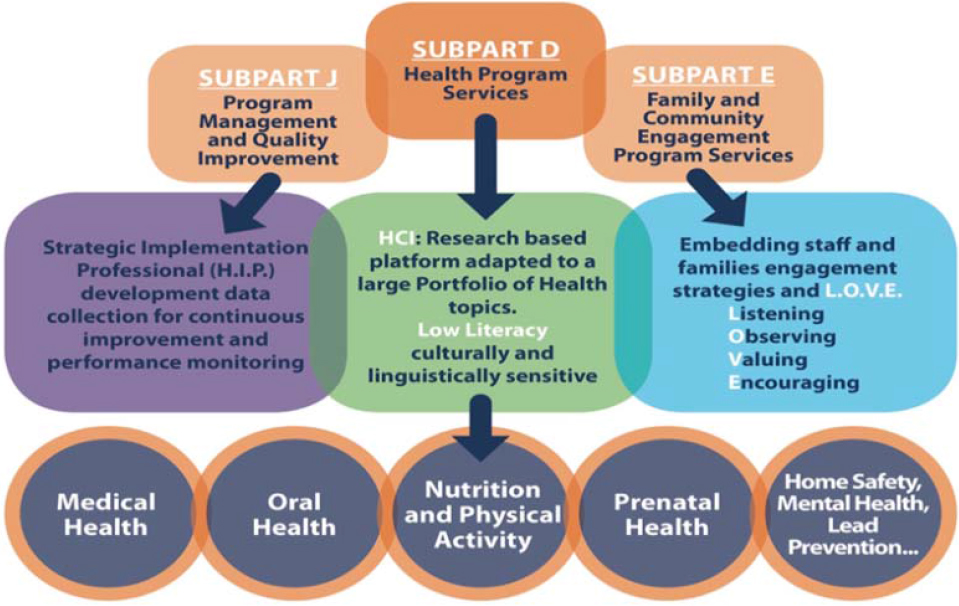

UCLA campus to receive management training. In 2000, she surveyed 600 of these directors, and they identified poor health literacy and poor attendance as obstacles to better health outcomes for the families they serve. In response, she and her collaborators founded the Health Care Institute (HCI) in 2001 with the mission of strengthening the managerial capacity of Head Start agencies so that they can provide health education and prevention programs that attract 80 percent of the families to outreach activities and provide culturally sensitive materials that family members can understand and use to take action to improve the health of their families.

Herman noted that her program has benefited from steady financial support from funders, including Johnson & Johnson, the Office of Head Start, the National Center for Early Childhood Health and Wellness, the Fidelity Charitable Fund, the State of Washington, the Kansas Head Start Program, and Pfizer. Another key to success has been the partnership that she and her team have developed with the national Head Start community. “They know we are on their side,” she said. All told, Herman and her team have reached 140,000 families across the nation. They have conducted training in seven languages, primarily in Head Start and Early Head Start programs and most recently in other daycare settings. Their experiences over the past 17 years, she said, have provided a number of important lessons regarding the factors that make community-based health literacy more effective. The first lesson has been that business management tools are key to enabling Head Start agencies to successfully define goals, objectives, and an action plan, as well as gaining the commitment of leadership. It is important, she said, to give Head Start agencies the tools to engage staff, parents, and the community, and to provide them with low literacy, culturally sensitive materials written at the third or fourth grade levels. Flexibility is also important, because Head Start reaches so many different types of communities, each with its own culture and health needs, and data are key for continuous quality improvement. Above all, said Herman, it is important to establish an organizational culture based on L.O.V.E.—listening, observing, valuing, and encouraging. That slogan, she noted, was created by a Head Start director. “When it trickles down in the community, it really strengthens the impact,” she said.

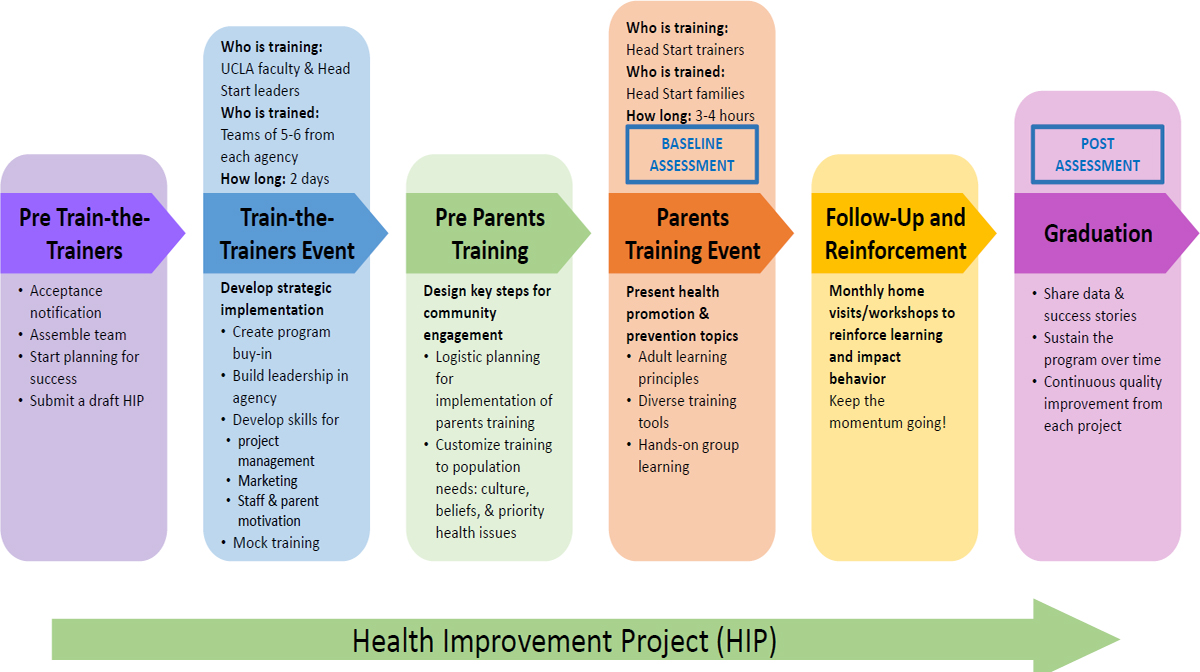

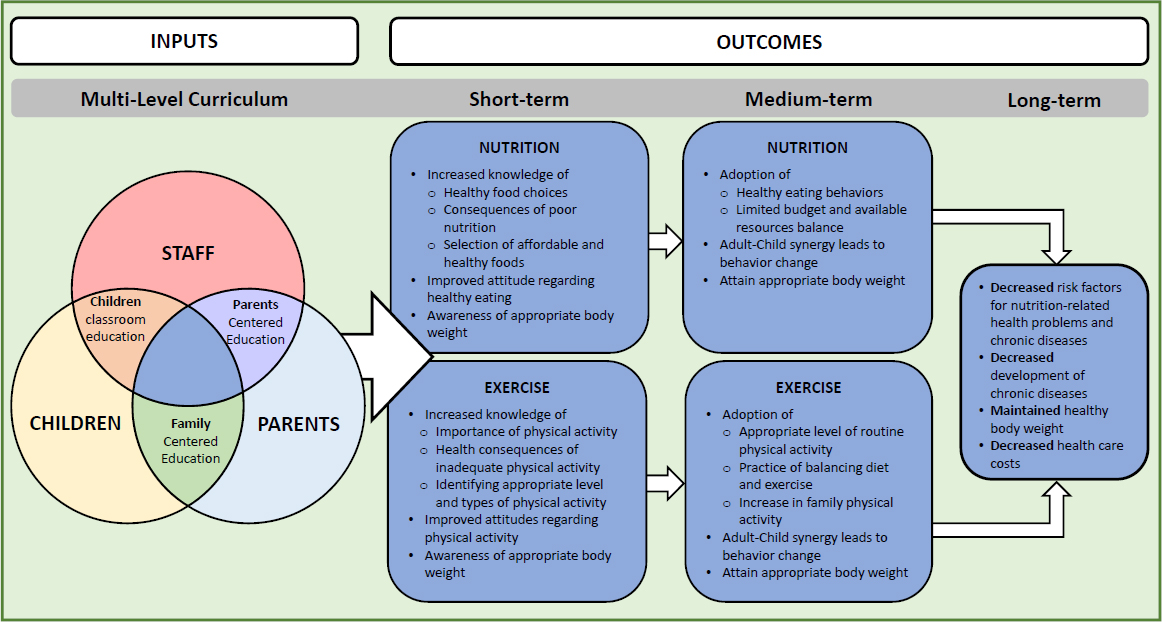

The strategic implementation model that Herman’s team uses (see Figure 3-3) consists of multiple steps because as she put it, “no change happens without intention and without planned activities.” The process starts with UCLA faculty and Head Start leaders training the trainers from Head Start agencies. “We share with them the tools on how to strategically implement health education and health promotion,” said Herman. “They go back and then they train their families on different health topics.” There are also reinforcement activities to make sure lessons from the trainings take hold and to keep the momentum going forward. This model is sustained by what

NOTE: HIP = Health Improvement Project; UCLA = University of California, Los Angeles.

SOURCE: Adapted from a presentation by Ariella Herman at the Community-Based Health Literacy Interventions workshop on July 19, 2017.

is known as the Health Improvement Project, an activity in which every Head Start agency must participate. It involves getting agency leadership to think about how they can engage their staff members so that they in turn will engage their families and the community. The Health Improvement Project also teaches agency leadership how to identify resources in their community, implement new programs, develop an action plan and budget, and collect data for evaluation purposes.

One of the training tools used with families is What to Do When Your Child Gets Sick, a book from the Institute for Healthcare Advancement. This book is available in multiple languages, and trainings of Head Start families are often conducted in multiple languages. “We are not trying to change tradition,” said Herman. “We are trying to give understandable health tools to families so they can take action relative to the health of their children.” Training is very hands-on, she noted, and aims to teach the core of what families of young children need to know, starting with common childhood illnesses.

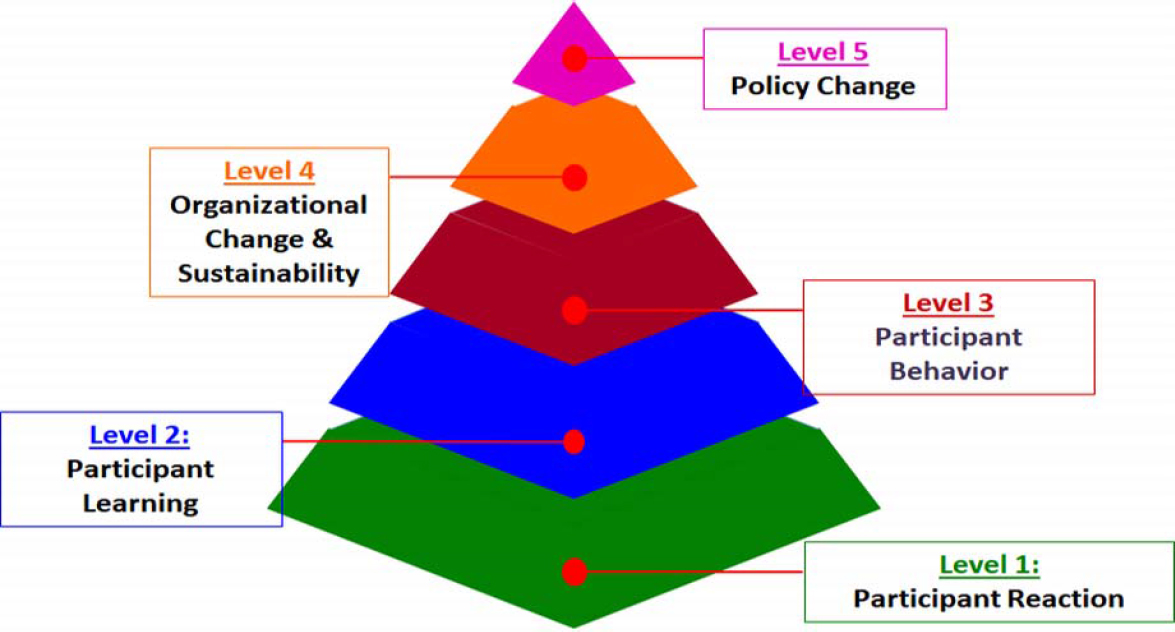

Over time, HCI has developed a five-level evaluation process (see Figure 3-4). Level 2 evaluation, for example, uses surveys at the end of the train-the-trainer phase to assess staff knowledge. It also uses surveys and focus groups at the end of health literacy trainings to assess what parents have learned, and it administers both pre- and posttraining surveys to measure knowledge changes in staff and families. Level 3 evaluation assesses how the trainings affect behavior. In one study, parents were asked where they go first for help when their child is sick. Before training, 75 percent of parents said they would take their child to the doctor or emergency room, while after training nearly half said they would refer to a health book written at the third grade literacy level (Herman and Jackson, 2010). Similar behavioral changes occurred during pre- and posttraining on how to take a child’s temperature and what to do when a child has a temperature of 99.5°F. Training, said Herman, produced a 29 percent drop in the average number of school days missed and a 42 percent drop in the average number of work days that a parent missed. Similarly, training reduced doctor visits by 42 percent and emergency department visits by 58 percent.

Qualitative assessment of outcomes for families and staff has shown that this program increases parental awareness of health warning signs, prompts parental response to early signs of illness, and leads parents to the appropriate use of health reference materials for first-line help. Families also report that they have a better understanding of common childhood illnesses, communicate better with health care providers, and make more effective use of health services. Herman’s team has also found that training increases engagement of parents and staff in health decisions. “Working with Head Start communities, where it starts with pregnant moms and goes to parents of children ages 0–5, this is the perfect time to start engag-

SOURCE: As presented by Ariella Herman at the Community-Based Health Literacy Interventions workshop on July 19, 2017.

ing families because they care about their children,” said Herman. “When you give them the right tools, it definitely makes a difference.” Quoting a letter she received, she said, “A parent who has the tools to make appropriate decisions about the health of their child has been given self-esteem. When a person has self-esteem, they can move a mountain,” said Herman. “Mountains have been moved in the lives of the families that I work with through health education with L.O.V.E.”

Herman’s team has conducted Level 4 evaluations using long-term impact surveys of grantees they trained 5–10 years ago, well after their funding to implement the Health Improvement Project had ended, and found an increase in cross-sector collaboration within their communities. They also found that while the training focused on common childhood illnesses, many of the programs had adopted the model for a variety of health topics. With regard to sustainability, Herman and her collaborators surveyed 203 Head Start agencies from 50 states and found that 84 percent had sustained the Health Improvement Project activities beyond the initial year and 71 percent continued to provide this training annually without her team’s help.

The key predictors to sustainable success, Herman noted, included engagement of the leadership of the Head Start community and the community in which the Head Start program operated, as well as providing incentives and removing barriers to attending training sessions. Many Head Start agencies have included funds in their training budgets to send teams to HCI so that staff turnover does not bring the program to a halt (Nelson et al., 2014). Nearly 70 percent of the grantees reported that they leverage community resources to sustain HCI training and 72 percent said that they have been able to continue providing incentives to parents as part of the training program. In addition, 89 percent of the grantees have adapted training to meet the needs and design of their local program, 82 percent were able to engage and motivate their leadership team to continue the training program, and 80 percent said that they have been able to engage and motivate staff to continue the trainings.

In 2017, Herman and her colleagues created a new online survey for both agency leadership and families that have participated in past trainings. The goal of the new survey was to identify the critical elements that foster strong, impactful health education and family engagement. “What grantees know is that once a family came to one training, they were standing in line to come to others,” said Herman. “Every parent wanted this kind of information when it was given to them with respect and with materials that they can use and understand and that is adaptable to their needs.” From the survey, her team found that the most important things agencies can do to continue to engage families were to first provide a meal—a meal means a great deal for these underserved families—and then deliver low-

literacy messaging. Also important were rewarding parent participation in the interactive portions of training with prizes and having staff attend and mix socially with families.

With regard to which strategic elements of the HCI model were used by agency leadership to organize parent trainings, 74 percent reported that they used L.O.V.E., 85 percent used the Health Improvement Project activity, 75 percent relied on community engagement, 89 percent took advantage of parental motivation, and every grantee said that staff motivation was important. Herman said that the Health Improvement Project helps agencies repeat the training process in a strategic way. Every one of the 652 parents surveyed reported that they would recommend the training to a family member, friend, or neighbor, and 99 percent or more said that they were planning to use other health services in the community based on staff recommendations, that the training provided them with health information or other help that they needed for their children, and that the information presented during the training was easy to understand.

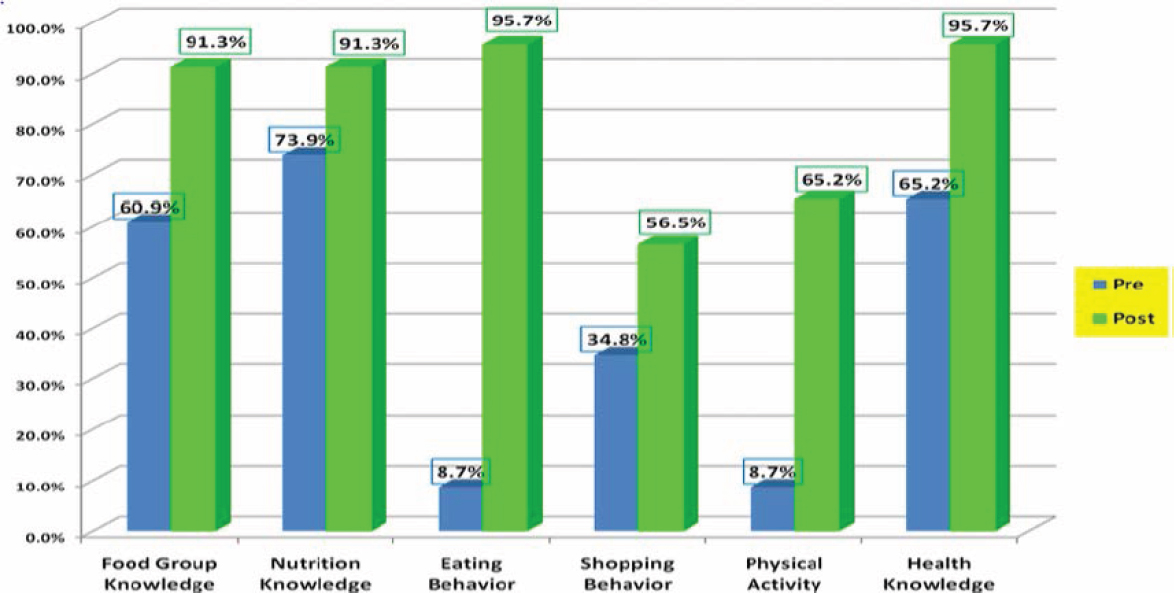

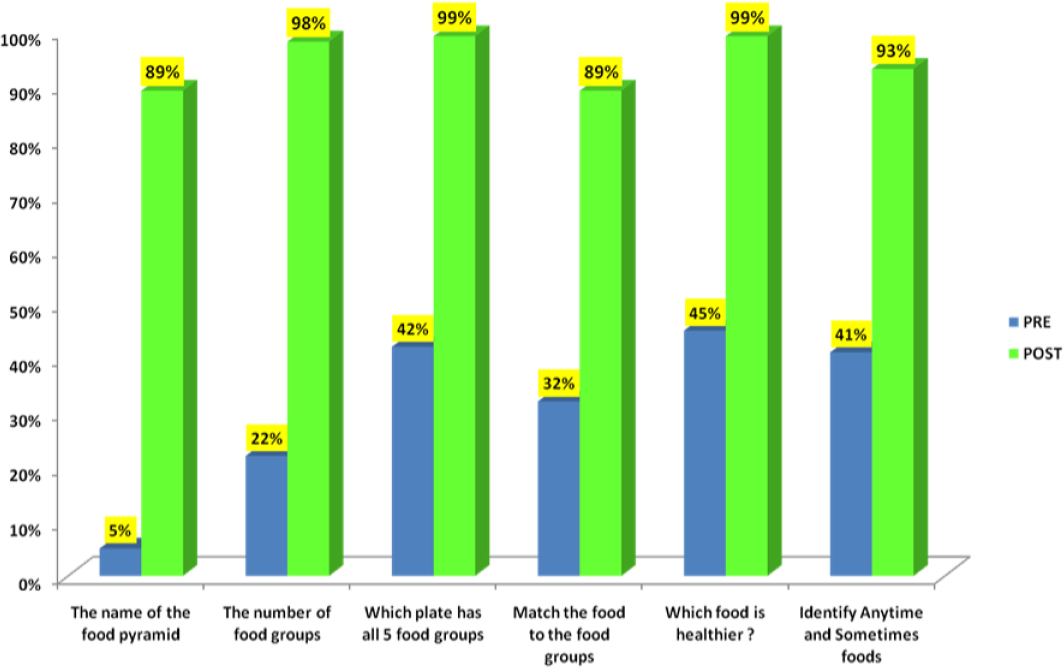

As she mentioned earlier, Herman and her colleagues found that once the method is understood and implemented, it is easily adapted with minimal investment to other health topics, including oral health, diabetes, obesity prevention, and prenatal care. As an example, she described the Eat Healthy, Stay Active model (see Figure 3-5) that trains staff, families, and children to have a stronger impact on both knowledge and behavior. Evaluation data showed that this program produces a significant increase in knowledge and behavior regarding healthy eating in both adults and children (see Figures 3-6 and 3-7). Perhaps most importantly, the percentage of children with a body mass index in the normal range increased from 59.8 to 65.2 percent and the percentage of children with a body mass index in the obese range fell from 30.4 to 20.5 percent when measured 9 months after training (Herman et al., 2012). She noted that at least one Head Start program created a farmers’ market where children can learn how to buy food, and when they bring the food into the classroom, the children learn about calories and how to cut food and taste it, while also learning numbers and math.

Evaluations of policy change, Herman said, have documented changes at the system level in both Head Start grantees and the Office of Head Start Policies. Health literacy, for example, is now included in new Head Start performance standards released by the Department of Health and Human Services (see Figure 3-8). Health literacy has also been included as a crosscutting concept for the Office of Head Start’s National Center for Early Childhood Health and Wellness, she noted.

With regard to her team’s greatest successes, Herman noted that the HCI model strengthens management’s capacity to better plan and implement health trainings; measure the impact of training on parents; meet multiple performance standards; use data to implement continuous quality

SOURCE: Adapted from a presentation by Ariella Herman at the Community-Based Health Literacy Interventions workshop on July 19, 2017.

NOTE: n = 497.

SOURCE: As presented by Ariella Herman at the Community-Based Health Literacy Interventions workshop on July 19, 2017.

SOURCE: As presented by Ariella Herman at the Community-Based Health Literacy Interventions workshop on July 19, 2017.

NOTE: H.I.P. = Health Improvement Project.

SOURCE: As presented by Ariella Herman at the Community-Based Health Literacy Interventions workshop on July 19, 2017.

improvement; build an internal culture of health and wellness; and enhance job satisfaction. The program has also strengthened community partnerships to collaborate on building a culture of health in the broader community, and it provides ready-to-use tool kits to equip communities to foster health and practice prevention. In addition, HCI’s efforts have improved the health literacy of Head Start staff and families and increased staff, parent, and community engagement.

Finding funding for implementation has been one of the program’s biggest challenges, as has explaining how all of the elements of the method are integrated, essential, and contribute to success. Herman said that she and her colleagues have learned that shortening the trainings, expecting less from trainees, not providing materials, or providing materials without training does not work as well. They have also learned how important building a team and building leadership are to success. One challenge going forward, said Herman, is figuring out how to embed this program in other settings, such as childcare and public school, that are heterogeneous and differently resourced. Other challenges going forward include determining how to take the next step to build parents’ health advocacy in their own communities, how to ensure that the knowledge and experience of she and her collaborators at HCI can be transferred to an entity that can spread this work more broadly and continue to evolve it, and how to link this work with medical students, providers, and medical centers. Herman also pointed out that governmental and institutional policies will be critical for creating and sustaining demand and support for health literacy activities.

As her final message, Herman said that her team has seen that family engagement is fostered through health literacy and a management system approach. “Once parents have the knowledge, tools, and motivation to protect the health of their children, and barriers are removed, then meaningful change can occur,” said Herman. “With a systematic approach to community-based health literacy interventions, we can make a difference. We can help set entire families and communities on a better health trajectory.”

MODERATED PANEL DISCUSSION6

To start the discussion, Earnestine Willis asked the panelists to elaborate on how they set priorities for action when it comes to addressing the

___________________

6 This section is based on the comments by Marisa New, board member of the Oklahoma Health Equity Network and chair of the Southwest Regional Health Equity Council; Leslie Gelders, health literacy coordinator at the Oklahoma Department of Libraries; Catina O’Leary, president and chief executive officer of Health Literacy Media; and Ariella Herman, research director at the Johnson & Johnson Health Care Institute and senior lecturer on decisions, operations, and technology management at the University of California, Los Angeles,

concerns of the different stakeholders in a community. O’Leary replied that her team used a consensus model process that first involves getting as much input as possible from community members and then discussing the resulting ideas. “What we tried to do is come to an agreement with the community about what makes sense now within a short period of time and what we can then do to get more funding to do more over time,” explained O’Leary. Funding is not the only perspective, she added, given that many community partners have a limited amount of time that they can contribute to these activities. “We had to think about their bandwidth and what they could do now and what they want to do later,” said O’Leary. She noted that as long as her team kept the conversation going and listened carefully to what the community members were saying, the list of priorities became clear rather quickly.

When Willis asked her if her priorities changed after receiving a community’s input, O’Leary said that she comes from a background of community-engaged research and has the perspective that the priorities for action need to come from the community. “The strategies were not predefined for me,” she said, adding that there are some things that she knows will work and she would like to provide those to the community, but the choice is up to them. She noted that she was never surprised by the priorities that communities chose given her experience that most communities are after the same things.

New and Gelders said that their organizations take the same basic approach as O’Leary. “We did not tell them what their priorities were, but we told them where to find the resources that would help guide them,” said Gelders. She added that the Oklahoma Department of Libraries’ only priorities have been to provide resources so that public libraries could become active, visible, and effective partners in health literacy, and to help Oklahoma children, adults, and families get additional resources and access to information to improve their health.

Willis then asked the panelists if they considered how to evaluate their programs and if they had adequate tools to do so. Herman, a statistician, said that evaluation is always on her mind, and when she and her colleagues started their project in 2001, they decided to create evaluation surveys on different prevention topics. However, when they went into communities to see how they were implementing their projects, they found that half of the families did not fill out the surveys because the literacy level was too high. As a result, what started as a seven-page survey is now one page. “We grew our evaluation method with the feedback from the agencies,” she said. Herman added that every Head Start grantee received the survey data

___________________

Anderson School of Management, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

from their community so they could learn from it. She also explained that her team has not used health literacy evaluation tools and instead created their own evaluations.

O’Leary said that her team also thought about evaluation at the start of its project, but there were no available evaluation tools that they could use off the shelf. “The communities were so different and diverse that we had to create our own,” she said, adding that the availability of electronic tools such as Google forms and iPads enabled the team to create evaluation tools quickly and collect a great deal of data in real time in the four communities. One challenge the team faced was evaluating behavioral changes in the communities. “The question is whose behavior are we measuring when,” she said, referring to the fact that behavioral changes extended beyond the individuals who participated directly in the intervention. “I think the tools are weak everywhere, but in community work it is hard to find a good tool that works for every sort of question and problem,” said O’Leary. Her hope was that the workshop’s session on evaluation would provide some guidance on tools that are robust and usable.

The organizations funding Gelders’s project require evaluation, and every site involved in the project gets feedback from as many participants as possible. The sites then submit that information in the final project report. In addition, each site develops three measurable outcomes for their projects and reports on those outcomes. She said that there is always the opportunity and the need for new tools to evaluate these projects. New said that her coalition used the roundtable’s 10 attributes of a health literate organization as the basis for the evaluation tools it has used.

The next request from Willis was for the panelists to speak to some of the strategies they used for transitioning from laying the groundwork to raising community awareness and building capacity in the communities related to their programs. New said that her coalition had just started building its capacity in its communities, which involves building the capacity of individuals who would be willing to volunteer their time to projects that improve health in their community. Within her organization, she had to find champions who would help take information about addressing health equity and administer a survey with the coalition members, and then provide trainings to those organizations. “That was critical in taking [the project] from awareness building to actually integrating it into our institutions,” said New.

Gelders said that the first step for her project was to educate librarians about what health literacy means. An important service she provides is to be the person a librarian can call with questions, and to provide that service, she learned as much as possible about health literacy by going to a variety of conferences. “I did a lot of research so that I could provide

some information and assistance to these grantees,” said Gelders. She noted that her team holds regular conference calls for the grantees to share ideas, solve problems, and learn about best practices, and it also encourages them to share their successes at meetings such as the Oklahoma Library Association conference. Her team has presented at literacy conferences and at Oklahoma Health Equity Campaign meetings that are broadcast to most of the state’s county health departments. She also provides opportunities for the grantees to receive continuing education in health literacy, including through an annual summit she organizes, and by providing funds for grantees to attend the Wisconsin Health Literacy summit.

Herman said that her program had the luxury of starting small, with 200 families, during the first 6 years of her project thanks to funding from Johnson & Johnson. They were also fortunate to have worked in the creative and innovative environment of the Head Start program. Each year, she and her team would observe the trainings, get feedback on challenges and successes, and then enrich the curriculum based on that feedback. By 2008, the program was being used in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, which allowed the program to receive an innovation grant from the Office of Head Start and enabled her and her colleagues to make teaching health literacy part of what Head Start agencies do when providing comprehensive services to families.

Next, Willis asked the panelists how they developed and sustained the resources to implement their interventions, particularly with regard to finding staff and volunteers. Gelders replied that her program received a grant from the Library Services and Technology Act funds awarded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. These funds, she explained, are federal dollars given to state libraries to address priorities listed in that Act, and her program’s health literacy projects address at least three of those priorities. Gelders noted that the project has received a budget increase every year that she has been involved with the project and her agency, allowing her to dedicate an increasing amount of time and effort to the project. As far as the grantees themselves are concerned, they use a mix of paid library staff, volunteers, and paid presenters. They also network with other health literacy programs in their communities. “They have been successful in getting in-kind and community support,” said Gelders. She noted that many organizations are interested in health literacy, are looking for partners, and are willing to provide their services at no charge. She added that the Institute of Museum and Library Sciences is one of the agencies that the current administration has proposed eliminating.

New said that her coalition does not have any direct funding support, and it recently decided to become a nonprofit organization in the hopes that doing so will expedite its efforts to work with the Department of Libraries and other public and private institutions. In past years, the coalition sus-

tained its efforts with in-kind contributions from volunteer partners and by working with entities whose interests lie beyond literacy, such as housing. “We are not talking specifically about health literacy, but [we] are talking about health and how we want to see health improved,” said New. “Health literacy is key, but working with our non-traditional health partners has been one of the best things to leverage our resources and opportunities in Oklahoma.”

Willis noted that when she surveyed other audiences interested in health literacy interventions in their communities, she heard that time is a scarce resource. Given that, she asked the panelists if it took longer to build their programs than they expected and if time was a critical issue. O’Leary said that her organization received funding in May and then spent the next 4 months explaining to the Missouri Foundation for Health exactly how they were going to use the funds and how they were going to brand their project. Once that process was behind them, O’Leary and her colleagues had to pick the communities and have the communities agree to be part of the project, which took another 6 months of work and regular conversations with the selected communities. Now that the projects are running, her team has found that time is an important consideration. “We are constantly trying to get people to have coffee or lunch with us because those are the minutes that they have,” said O’Leary.

Herman said that she appreciated Willis’s question given that she has had 15 years to work on her project and learn from the different Head Start communities across the nation. She said that although her program’s resources were varied enough to satisfy the needs of those programs, the demand today is greater than what they can meet. She said that after about 6 years, Head Start agencies realized that her program exists to help them with their core missions and that the data her program shares with them can make a big difference to their activities. She noted that although her program has reached 140,000 families, they have 1 million more to reach. “We are not ready to retire,” she said.

As her penultimate question to the panelists, Willis asked if there were successful initiatives that did not go as planned, and if so, if there were lessons learned during the development and implementation phases. Herman said that what she has learned is that there is no cutting corners. “When you do not do it intentionally, you will not have impact,” she said. For example, some of her funders wondered why her program could not just distribute a book and measure impact or conduct training without distributing the book, but doing that did not produce the desired impact. O’Leary agreed completely with the need for activities to be planned and intentional, and added that once a program gets into the community, it has to be flexible enough to evolve with the community. “So many things do not go as planned, yet it all turns out okay as long as you are still there together,” she

said. One point O’Leary said that she should have mentioned in her presentation was about the importance of having humility, being humble and flexible, and recognizing that community members are the experts when it comes to identifying what their community needs.

Gelders said that her program has been highly successful and has had no failures. One outcome that she hoped was about to be successful will have been the direct result of her attending the workshop. To be at the workshop, she had to get permission from the cabinet secretary for out-of-state travel. As a result, the cabinet secretary requested a meeting with her to talk about health literacy and what she learned from attending the workshop. “I am hoping this will be another big success,” said Gelders. New said that the Oklahoma Health Equity Campaign is changing what it is doing as it transitions to being a nonprofit organization. She believes that this change will expedite other changes happening in relation to health literacy as its primary determinant and to advance health equity.

Willis’s last question for panelists was whether they share data with their stakeholders. O’Leary replied that sharing data is essential to helping the local programs make decisions about what they are going to do next. New said that program documents on a projector screen in real time, showing what people are saying at community forums, is something that participants appreciate. One reason for the coalition existing is to get comments from the public and provide them to city councils, Oklahoma Health Improvement Plan committees, and other stakeholders, she noted. Gelders replied that her program shares all of its data with its grantees. In addition, because her program receives federal funds, it must report statistics from each site as well as overviews and comments, all of which are publicly available.

DISCUSSION

Bernard Rosof opened the discussion by asking Herman if her program had any data on its effect on childhood immunization. Herman replied that those data are coming.

Cindy Brach from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) asked O’Leary what criteria she used to decide which tools worked and what she did if a community had a need for which there was no evidence-based intervention. O’Leary replied that what works are the tools developed over several years of working with the Cover Missouri Coalition. She has learned from talking to assisters and navigators that many of the materials and resources that communities have are not accessible, and that her team can help with language and quality and get communities to expect materials to reach a higher standard. “We have data about what kinds of trainings and programs can help people change their knowledge, skills, and attitudes,” she said. “We know that we can help people get to the point that

they can make the best decision for themselves and their family. We have trainings to help people do that.” In particular, she and her colleagues can deliver all of the materials that are the bread and butter of health literacy and have evidence to support their effectiveness. Her team has also developed a training menu for all of the program’s community partners, and all of these trainings have been vetted and approved based on evidence and are available to the community. Her program has measures of satisfaction for some interventions, such as sending the program’s public relations partner into communities to teach people how to do an interview with the media about health insurance, but the evidence is “looser.”

As far as what she does when a community asks for something for which her program does not have an evidence-based solution, O’Leary said that she has 25 smart people who have the skills to find information, put it together in an accessible way using health literacy strategies for the appropriate audience, deliver it to the requesting community, and then solicit the community’s feedback. “We do not make up messages, but get them from the evidence across the board,” she said. For more difficult requests, she relies on the interns that her program gets from the graduate programs in the St. Louis area.

Paasche-Orlow asked New if she believes that health literacy is a social determinant of health. She replied that when she and her colleagues developed the position statement for their program, they looked at different sectors of the community and came to the conclusion that literacy was a foundational element connecting education and health. “Literacy is the determinant I am focusing on when I talk about health literacy,” said New. Paasche-Orlow then commented that when states measure social determinants of health for purposes of risk adjustment in their Medicaid programs, they do not include health literacy as one of the items they measure. O’Leary replied that as a social worker, she would consider health literacy as not exactly a social determinant of health, but more of a crosscutting theme. Herman said that she would say that health literacy is a social determinant of health, but the problem is in how to measure it. Rosof commented that this may be the subject for a future roundtable workshop.

Terry Davis from the Louisiana State University Health Science Center in Shreveport asked Herman how she managed to create a one-page assessment that people can understand and respond to independently. Herman replied that it took 5 years and multiple rounds of developing surveys and getting feedback from focus groups to try to understand why they were not answering certain questions. Even then, difficulties arose when they translated the survey into other languages.

Andrew Pleasant from Health Literacy Media noted that each panelist has managed to “embrace the lovely messiness of community,” and he asked them for any advice that they could provide to the states, cities, and

neighborhoods that are trying to create coalitions and umbrella organizations. New said that her advice would be to get involved in a community beyond merely doing one’s job by volunteering and being part of a civic organization or professional association. “Those that have been involved in our efforts have been those people who are the movers and shakers,” she said. “Oftentimes, we say those are the same people at every table, but those are the people who are really doing things.” One impact that she has seen recently is that those same people have started mentoring others to be involved in making things happen. “You have to go beyond just your work to share the message in many different ways that relate to those people you are encountering on a daily basis,” said New.

Gardenier made a comment about the importance of paying attention to differences in perception and comprehensibility when sharing data with communities. She then asked how the Head Start project relates to the data Herman presented on emergency medicine and primary care. Head Start starts at pregnancy and serves children and families with children ages 0–5, said Herman, and she and her colleagues have learned over time that parents care for their children in the best way they can. When parents do not know if a child is too hot, they run to the emergency department, and when they do not know the difference between a teaspoon and a tablespoon, they can easily overdose a child and end up in the emergency department. “That is why we introduce hands-on tools over time, distributing thermometers and teaching them how to use them and what to do first instead of rushing to the emergency department,” said Herman.

Wilma Alvarado-Little from Alvarado-Little Consulting, LLC asked if Herman knew of any partnerships that might be considering extending what her program has done with Head Start agencies to the elementary school setting. Herman replied that her program is trying to give families the confidence to understand and use health information, and she has not been able to track what happened to these families when their children moved on to public school. What she has seen, though, is that a large percentage of these families become part of the policy council and become strong advocates for children. “For us, it is a start at the moment when parents are most open to learn and to get the tools they need, but by no means do we provide a lifetime of tools,” said Herman. Willis, who happens to be the chair of a Head Start board, said that many Head Start programs do have partnerships with school districts, and that with new performance standards, she believes there will be more tracking into the secondary school setting.

Lindsey Robinson from the American Dental Association thanked O’Leary and Herman for emphasizing oral health in their programs. She said that it is often an unmet need in many communities and is an important contributor to overuse of the emergency department. She then asked

Herman if her program has been able to measure its impact on families and communities as a whole. Herman said that her program’s oral health prevention model is geared toward parents at the beginning of pregnancy and toward children, and she has not measured the community impact. “We did measure the impact in the community for our Eat Healthy, Stay Active model, where we measured the impact on families’ knowledge, behavior, and weight, but also the families going into the community and making changes on what needs to happen and being much more active,” said Herman.

Gem Daus from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) asked O’Leary if she has had the opportunity to observe communities acting on their own initiative to teach others and diffuse these innovations without the so-called experts in the room. O’Leary replied that because of the coalition’s relationships, she and her colleagues have been in these communities for several years and have seen the resources they possess, but they have monitored what happens when the project team is not actively involved in the intervention. Herman commented that her program just completed a survey of Head Start programs and found that the thousand or so responding agencies all reported that they had become the center of information in their neighborhoods and are now going out into the community to give talks and discuss the resources they have. “That is, I believe, the first step toward expanding,” said Herman.

Jay Duhig from AbbVie asked the panelists for their ideas on the greatest opportunity for using Web-based interventions to improve community-wide health literacy. O’Leary said that most of the issues that her communities raised had to do with eating, exercise, and moving, so while a Web-based program can provide information, the actual activity people need to do is best done with others. “Diet is not fun or exercise is not fun until you start to do it and make friends,” she said. The opportunity she sees for Web-based programs is to provide information and facts and to build communities that connect people. Gelders said that this is where public libraries can play a role because they not only have the technology, but also spaces where people can gather and have the personal interaction that O’Leary mentioned.

The final question in this session came from Rudd, who asked the panelists to address the tension between the need to measure and gather baseline data and the pressure to take action. O’Leary said that tension always exists, and one challenge is putting the systems in place to make sure that any data that is collected gets reviewed and used. “Nobody wants to pay for that, and it is expensive and complicated,” she said. New noted that it takes a great deal of time and effort to not only prepare a survey, but also to get it to the right person so that the response is meaningful. Herman said that her program does not experience that tension because of the partnerships it

creates with the Head Start grantees. “They know that we are giving them the tools to be able to succeed, but as part of the contract, they know that they need to provide the data that we then analyze and share with them. It is a give and take on both sides,” said Herman. “We are there for them if they have barriers, but they know that this is part of their responsibility to provide both qualitative and quantitative data, and they also see how we use it to make progress.” Rosof added that anybody involved in quality and improvement work knows that tension. “It exists every day, but it should not arrest innovation,” said Rosof.

This page intentionally left blank.