10

Dissemination and Implementation

The gap between discovery of public health knowledge and application in practice settings and policy development is due in part to ineffective dissemination.

The dissemination and implementation of scientific evidence into regular and effective use is complex due to the multiplicity and capacity of health care systems and providers and the diversity of the target audiences. However, such efforts are imperative in order to improve the quality of care, patient outcomes, and population health. Several reports of the Institute of Medicine describe opportunities for the implementation of evidence to improve population health and health care delivery (IOM, 2009, 2011a,b, 2012, 2013, 2015). The gap between the existence of evidence-based practices and the application of such practices has been linked to poor health outcomes (Conway et al., 2012; Shever et al., 2011; Sving et al., 2012). Two main challenges exist for the dissemination and implementation of information related to the social isolation and loneliness of older adults. First, better dissemination is needed regarding the evidence of the health impacts of social isolation and loneliness. Second, the best practices of implementation science will need to be used in order to ensure that health care systems and providers are able to more quickly adopt evidence-based practices. This will be particularly important as the evidence base on the effectiveness of specific interventions for social isolation and loneliness improves.

DEFINITION OF TERMS

Multiple and inconsistent terms are used in the field of dissemination and implementation science (Rabin and Brownson, 2018). For purposes of this report, evidence-based practice is defined as the conscientious and judicious use of current best evidence in conjunction with clinical expertise, patient values, and circumstances to guide health care decisions (Straus et al., 2010; Titler, 2014). Ideally, when enough reliable research evidence is available, practice is guided by findings from research in conjunction with clinical expertise and patient values. In some cases, however, a sufficient research base may not be available, and health care decision making relies on other evidence sources, such as scientific principles, case reports, and outcomes of quality improvement projects.

Dissemination research in health is the scientific study of the targeted distribution of evidence-based information and intervention materials to specific public health or clinical practice audiences with the intent of spreading and sustaining knowledge use and evidence-based interventions (HHS, 2018). The mechanisms and approaches to packaging and conveying the evidence necessary to improve public health and community and clinical care services are dependent on the type of audience (users), how the messages are framed, and the local context in which users reside, work, and live. For example, successful dissemination of health information may occur differently, depending on whether the audience consists of consumers, caregivers, practitioners, policy makers, employers, administrators, or other multiple stakeholder groups.

Translation science, more recently known as implementation science, focuses on testing interventions to promote the integration of evidence-based practices in order to improve patient outcomes and population health and also to explicate what implementation strategies work for whom, in what settings, and why (Eccles and Mittman, 2006; HHS, 2018; Titler, 2010, 2014). Implementation research seeks to understand the practice behaviors of health care professionals, health care organizations, consumers, and policy makers in their respective contexts or settings (HHS, 2018).

Evidence-based practice and implementation science, though related, are not interchangeable terms. Evidence-based practice is the actual application of evidence in practice (the “doing of” evidence-based practice), whereas implementation science is the study of implementation interventions, factors, and contextual variables that affect knowledge uptake and use in practices and communities.

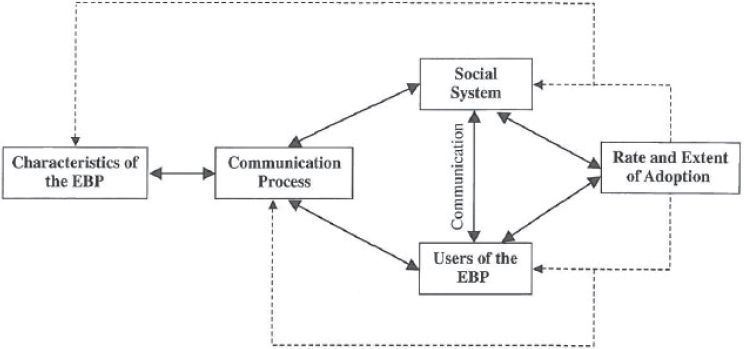

The translation research model (Titler and Everett, 2001; Titler et al., 2009, 2016; see Figure 10-1) is based on Rogers’s (2003) diffusion of innovations framework in which the rate and extent of the adoption of evidence-based health care practices are influenced by the nature of the innovation (e.g., clinical topic for the evidence-based practice) and the manner in which the innovation is communicated to the users of the evidence-based practices within a social system. Successful implementation requires strategies to address each of these areas (Titler, 2010; Titler et al., 2016).

NOTE: EBP = evidence-based practice.

SOURCE: Adapted from Titler et al., 2016.

An important principle to remember when planning for implementation is that the attributes of the evidence-based practice topic as perceived by users and stakeholders (e.g., ease of use, valued part of practice) are neither stable features nor sure determinants of their adoption. Rather, the interaction among the characteristics of the evidence-based practice topic, the intended users, and the context in which practices will be implemented all determine the rate and extent of adoption (Dogherty et al., 2012; Greenhalgh et al., 2005).

OVERVIEW OF IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES

To narrow the gaps between the known evidence and what is applied in routine health care, implementation scientists have prioritized the development, refinement, and testing of implementation strategies. Implementation strategies are methods or actions (i.e., interventions) to promote and facilitate the adoption, implementation, sustainment, and scale-up of evidence-based programs, practices, or models of care. Interventions can be discrete, involving one action or process (e.g., clinical reminders), or they can consist of two or more discrete strategies (Kirchner et al., 2018).

The challenges facing implementation include the inconsistent terminology used in naming and defining implementation strategies, the lack of an agreed-upon taxonomy, and the variations in how the implementation strategies are operationalized (e.g., who is targeted, who delivers it, temporality). The following sections describe implementation strategies that address each of the four components of the model illustrated in Figure 10-1.

ADDRESSING THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE TOPIC

The complexity of a topic influences implementation. For example, evidence-based practices to decrease the social isolation and loneliness of older adults will likely include several actionable recommendations applicable across health care settings and the community (Andermann, 2016; Malani et al., 2019; Veazie et al., 2019). Several implementation strategies can be used to address the characteristics of the topic. For example, quick reference guides give targeted concise information in a manner to assist those implementing recommendations in performing specific tasks (Titler, 2018). A variety of quick reference guide formats are available, such as laminated checklists and decision-making algorithms. Quick reference guides concisely and accurately convey essential actions and information from the practice recommendations and are accessible at the point of care delivery (Anderson and Titler, 2019; Arditi et al., 2017; Pantoja et al., 2019). The design and content of quick reference guides will affect their use in practice and the subsequent implementation of evidence-based practices (Flodgren et al., 2016; Versloot et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2016). As discussed in Chapter 9, Humana developed a one-page (two-sided) guide for physicians that focuses on defining social isolation and loneliness, highlighting the major health impacts of social isolation and loneliness, presenting the three-item UCLA Loneliness Scale, and advising physicians on potential referrals and resources (e.g., area agencies on aging, ride-sharing services, food resources) (Humana, 2019).

The empirical support for electronic clinical decision support interventions is mixed (IOM, 2011a). Reminders embedded in electronic health records have small to modest effects on clinician behavior and appear to be more effective when included as part of multi-faceted implementation strategies than when used alone (Anderson and Titler, 2019).

Conveying key messages about recommended practices at the point of care delivery is another way to foster the implementation of recommendations and is useful for reducing complexity. Distilling the recommendations to a few key points on visual displays can be very effective when the displays are designed appropriately. Examples include posters and infographics. Selecting the key message tools to promote implementation requires consideration of the knowledge of the end users, the context in which the tools will be used, and their design and usability (Flodgren et al., 2016; Grimshaw et al., 2012).

ADDRESSING USERS OF THE EVIDENCE-BASED INFORMATION

When designing implementation strategies that address the users of the evidence-based practices, it is essential to first delineate the targeted audiences or key stakeholders for the use of the information as well as the nature of the context in which they work or interact with the specified patient population. For example, interventions to decease social isolation may include social workers, psychologists, public policy makers, community health workers, and clinicians such as primary

care physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, mental health care providers, and physical therapists (among others). The interventions may target the general population to increase awareness about the issue (i.e., social isolation, loneliness) and considerations for addressing it.

Members of a group such as individuals within a health care system (e.g., nurses, physicians, community health workers) influence how quickly and widely evidence-based practices are adopted (Rogers, 2003). Implementation strategies that have demonstrated effectiveness in improving evidence-based practices of the users include performance gap assessment, audit and feedback, trying the evidence-based practice, engaging with the recipients of the evidence-based practices to address their values and preferences (e.g., shared decision making), and ongoing meetings to address barriers and acknowledge success (Fønhus et al., 2018; Greenhalgh et al., 2005; Hysong, 2009; Hysong et al., 2006, 2012; Ivers et al., 2012; Stacey et al., 2017; Titler and Anderson, 2019). These strategies are discussed in the following sections.

Performance Gap Assessment

Performance gap assessment is the provision of baseline or current practice indicators at the beginning of a practice change. It is used to engage clinicians in discussions about the current practice and about the formulation of strategies to promote alignment of their practices with evidence-based practices. As discussed in Chapter 7, many health care delivery systems are exploring practice-based strategies to identify and address the social determinants of health (including social isolation and loneliness); yet, clinicians may see such approaches as burdensome. As evidence-based practices for social isolation and loneliness emerge, performance gap assessment could provide the opportunity for clinicians to engage in the alignment of their practices for the implementation of these evidence-based practices.

Audit and Feedback

Audit and feedback is the ongoing auditing of performance indicators, aggregating data into reports, and discussing the findings with practitioners on a regular basis during the practice change (Hysong, 2009; Hysong et al., 2012; Ivers et al., 2012). This strategy helps clinicians see how their efforts to improve care and patient outcomes are progressing throughout the implementation process (Ivers et al., 2014).

Trying the Evidence-Based Practice

The users of evidence-based practices usually try the method for a period of time before fully adopting (Greenhalgh et al., 2005; Rogers, 2003). When an

evidence-based practice is given a trial as part of an implementation, users have an opportunity to use the evidence-based practice, provide feedback to the implementation team, and modify the practice as necessary. This feedback loop will be key to Recommendation 7-1, the performance of assessments to identify social isolation or loneliness in older adults. As the committee noted, more needs to be learned about who should receive assessments, who should conduct the assessments, the ideal frequency of assessment, and appropriate referrals. Feedback garnered by the initiation of assessment in clinical settings will provide valuable data on how to best intervene.

Engaging with the Recipients of the Evidence-Based Practices

An important component of implementing evidence-based practices is engaging with the recipients of the practices to address their values and preferences. Putting the patient, family, and community at the center of health care decisions is a core component of implementing evidence-based practices. It is essential to address patient values, characteristics, and contextual factors that are important to them. This is similar to the finding in Chapter 9 that a common factor of many successful interventions for social isolation and loneliness is the active engagement of the older adult in the design of the intervention itself to ensure that the voice of the individual is at the center of interventions.

Furthermore, shared decision making is a process by which patients and health care workers partner to make informed health decisions that benefit the patients and are aligned with consumers’ knowledge and values (Msowoya and Gephart, 2019). One approach to promoting shared decision making is the use of patient decision aides. Patient decision aides (also known as shared decision-making aides) are evidence-based documents or tools that support patients by making decisions explicit, providing information about options and associated benefits and harms, and helping to clarify congruence between decisions and personal values (Msowoya and Gephart, 2019; Stacey et al., 2017). These types of processes will be important, again, to ensure the autonomy of individuals who are identified as socially isolated or lonely. Participation in interventions, and personal preferences for lifestyle (e.g., living arrangements, community participation) need to be respected and honored in interventions.

When engaging patients, families, groups, and communities in health care decision making, it is important to be attuned to health literacy, health numeracy, and primary language. Health literacy, or the ability to understand written information about health, and health numeracy, the ability to understand quantitative data or information presented as numbers or graphs, are important for health care decision making. Thus it is necessary to ensure that patient materials and tools are in the patient’s primary language and convey the appropriate meaning following translation (Msowoya and Gephart, 2019).

Meetings with Key Stakeholders

Another implementation strategy is to have regular meetings with key stakeholders and those implementing the evidence-based practices in order to track the process of implementation, provide guidance, address questions that arise, solve ongoing challenges, and share implementation strategies that are working (Titler et al., 2009, 2016).

COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES

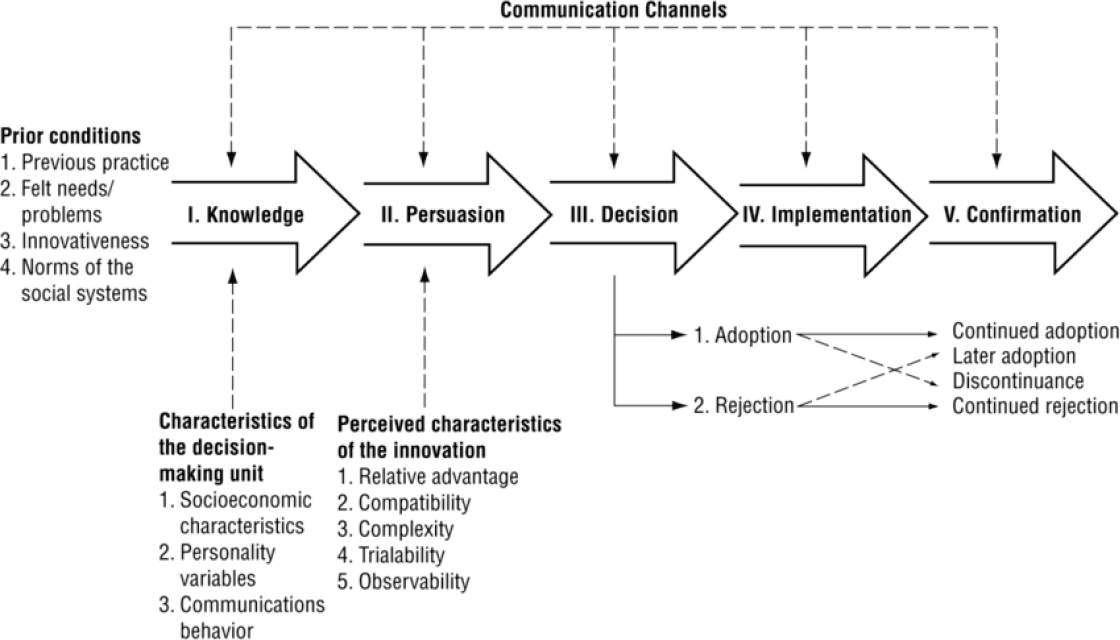

Information and shared understanding move through communication channels, such as mass media, and interpersonal or interactive communication routes, such as the Internet and social media. Which of the various communication strategies one uses for implementation depends on the stage of implementation (see Figure 10-2), the audience targeted for communication, the nature of the information to be communicated, and the desired outcomes. For example, if the desired outcome is to increase awareness about the impact of social isolation on the health of community-dwelling older adults, implementers may consider using mass media delivered through the Internet by professional organizations and consumer groups. (See Chapter 8 for more on public health campaigns.) When selecting communication strategies, it is important to be clear about the types of audiences to be reached and the information sources they use. This section describes the following communication strategies to promote implementation:

- Mass media and social media

- Education

- Opinion leadership and change champions

- Educational outreach

Mass Media and Social Media

Mass media and social media can help to address the initial steps of implementation—knowledge and shared understanding. “Mass media” refers to various technologies that allow for the imparting of information in a directional message from one source to many people. The primary channels of mass media are television, radio, print materials, Internet sources, and digital technology (Bala et al., 2017; Carson-Chahhoud et al., 2017). The characteristics of a mass media communication that influence the amount of attention that the communication attracts include the seriousness of the issue being discussed, the human interest (as with a personal story), timeliness, and conflict and controversy (Brownson et al., 2018a). The use of mass media to align clinician professional practices with the evidence most likely increases awareness and persuasion early during implementation (Grimshaw et al., 2012).

SOURCE: Rogers, 2003.

The definition of social media is broad and constantly changing, but social media can be thought of as a form of electronic communication using a variety of platforms through which users create online communities to share information, ideas, messages, and other content such as videos. Social media makes it possible for information and knowledge to be rapidly shared (Kirton, 2019; Roland, 2018; Ventola, 2014). The types of social media can be grouped by function (Djuricich, 2014; Kirton, 2019; Ventola, 2014), such as:

- Social networking—Facebook, Google Plus, Twitter

- Professional networking—LinkedIn

- Media sharing—YouTube, Flickr, Instagram

- Content production—blogs such as Tumblr and Blogger and microblogs such as Twitter

- Knowledge or information aggregation—Wikipedia

Although dissemination of evidence-based practice information through social media is significantly and positively associated with more downloads and citations of the evidence, it is unclear if the use of such dissemination pathways has a positive effect on practice behaviors (Brownson et al., 2018a; Puljak, 2016). Studies have demonstrated that the use of social media increases users’ knowledge about evidence-based practices and, based on self-reports, the application of evidence in their practice (Dyson et al., 2017; Frisch et al., 2014; Maloney et al., 2015; Tunnecliff et al., 2017). Bernhardt et al. (2011) describe how social media can be leveraged to enhance the dissemination and implementation of research evidence. More research using rigorous designs is needed to fully explicate the impact of social media on improving the knowledge, skills, and application of evidence in health care.

When using social and mass media, the considerations about messaging include knowing the audience, defining the customer, specifying the message and framing it, and selecting the communication channels (Brownson et al., 2018a; Steensma et al., 2018). A challenge for the dissemination of information related to evidence-based practices is defining the customer. “Failure to properly identify customers is the undoing of many valuable innovations” (Steensma et al., 2018, p. 193). Defining the customer helps frame the message and identify the proper communication channels and social media platforms for reaching them. This is particularly relevant for social isolation and loneliness in that there are likely a variety of underlying causes that likely require very key messages and intervention approaches.

Education

As discussed in Chapter 8, educating the users of evidence-based practices is necessary but not sufficient in order to change practice, and didactic education

alone does little to change practice behavior (Forsetlund et al., 2009; Giguère et al., 2012). There is moderate evidence that educational meetings that include both didactic and interactive learning are more effective in aligning professional practice behaviors with the evidence-based practices than didactic meetings alone or interactive learning alone (Forsetlund et al., 2009). Depending on the complexity of the evidence-based practices to be implemented, a variety of educational approaches can be considered, including train-the-trainer programs, high-fidelity simulation, and ongoing point-of-care coaching (Brownson et al., 2018a; Titler and Anderson, 2019). Many Web sources have packaged selected resources into implementation toolkits that include printed materials, training videos, and slide presentations. A toolkit could be developed for communities and health systems to facilitate the implementation of evidence-based practices to address social isolation and loneliness. For example, as discussed in Chapter 9, Humana created a Loneliness Toolkit (Humana, 2018) directed at consumers. The toolkit includes information on health-related issues (e.g., stress, substance abuse, vision and hearing impairment), staying engaged (e.g., transportation alternatives, housing options, use of social media), supporting loved ones (e.g., personal coping skills, caregiver support groups), and general community resources (e.g., area agencies on aging, ride-sharing services, support groups).

Opinion Leadership and Change Champions

Studies and systematic reviews have demonstrated that opinion leaders are effective in changing the behaviors of health care practitioners (Anderson and Titler, 2014; Cranley et al., 2019; Dagenais et al., 2015; Flodgren et al., 2011; McCormack et al., 2013; Van Eerd et al., 2016; Yousefi Nooraie et al., 2017), especially in combination with educational outreach or performance feedback. Opinion leaders are from the local peer group, viewed as a respected source of influence, considered by associates as technically competent, and trusted to judge the fit between the evidence-based practices and the local situation (Dobbins et al., 2009; Flodgren et al., 2011; Grimshaw et al., 2012). Opinion leadership is multifaceted and complex, with role functions varying by the circumstances, but few successful projects that have implemented evidence-based practices have managed without opinion leaders (Greenhalgh et al., 2005; McCormack et al., 2013). Opinion leaders among groups of older adults may encourage participation in interventions, most likely for community-based interventions.

Change champions are also helpful for implementing innovations (Dogherty et al., 2012; Rogers, 2003). They are practitioners within the local setting (e.g., clinic, patient care unit, public health agency) who are expert clinicians, are passionate about the evidence-based practice topic, are committed to improving the quality of care, and have a positive working relationship with other health professionals (Rogers, 2003). They circulate information, encourage peers to adopt the evidence-based practices, arrange demonstrations, and orient peers to the

evidence-based practices (Titler et al., 2016). The scope of influence that change champions have is usually within a specific unit or team within an agency, whereas the influence of an opinion leader spans multiple units or teams across an agency. For example, if an evidence-based practice tool to assess social isolation is being implemented across multiple primary care practices in a health system, to implement the practice, one nurse and one physician opinion leader could work across the practice sites in collaboration with change champions who are located in each primary care setting. This will be key to the implementation of Recommendation 7-1 (assessing for social isolation and loneliness) wherein the committee concluded that an important aspect of selecting a tool for use in clinical settings is standardization, meaning that within a specific health care system or organization all clinicians would use the same tool or set of tools rather than resorting to different tools.

Educational Outreach

Multiple studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of educational outreach, also known as academic detailing, in improving the practice behaviors of clinicians (Avorn, 2010; IOM, 2011a; O’Brien et al., 2007; Titler et al., 2009, 2016; Wilson et al., 2016). Educational outreach involves interactive face-to-face education and dialogue with practitioners in their setting by an individual (usually a clinician) with expertise in a particular topic (e.g., the prevention of social isolation). Academic detailers are able to explain the research foundations of the evidence-based practices and respond convincingly to specific questions, concerns, or challenges that a practitioner might raise. Clinicians’ perceptions of educational outreach as an implementation strategy are quite positive and perceived as helpful in overcoming implementation barriers (Wilson et al., 2016).

ADDRESSING THE SOCIAL CONTEXT

The social context for evidence-based practice implementation refers to the characteristics of the physical setting of implementation and the dynamic practice factors in which implementation processes occur (May et al., 2016; Shuman et al., 2018a; Squires et al., 2015). Context factors that affect implementation include

- Organizational capacity for evidence-based practice (Brownson et al., 2018b; Doran et al., 2012; Everett and Sitterding, 2011; French et al., 2009; Kueny et al., 2015; Stetler et al., 2009; Yamada et al., 2017),

- Leadership support (Aarons et al., 2014; Birken et al., 2016; Hauck et al., 2012; Jun et al., 2016; Richter et al., 2016; Riley et al., 2018; Shuman et al., 2018a; Wong and Giallonardo, 2013),

- Practice climates for use of evidence-based practices (Ehrhart et al., 2014; Jacobs et al., 2014; Shuman et al., 2018a; Yamada et al., 2017), and

- Evidence-based practices competencies of mid-level managers and supervisors (Gifford et al., 2007; Melnyk et al., 2014; Shuman et al., 2019).

The organizational capacity needed includes strong leadership, a clear strategic vision, good managerial relationships, visionary staff in key positions, a climate conducive to experimentation and risk taking, and effective systems for data capture and transforming data into information (Brownson et al., 2018b; Riley et al., 2018; Titler and Anderson, 2019). Elements of system readiness for assimilating evidence-based practices into care delivery include a tension for change, a fit of the evidence-based practices with the system, clear implications of adopting or not adopting the evidence-based practices, support and advocacy for the evidence-based practice topic (e.g., reducing the social isolation of community-dwelling older adults), the time and resources necessary for implementation, and the capacity to evaluate the impact of evidence-based practices on processes and outcomes of health care during and following implementation (Brownson et al., 2018b; Titler and Anderson, 2019).

When promoting the use of evidence-based practices, it is crucial to consider the context in which the potential users of the evidence will work because the settings for implementation are dynamic, and each setting carries its own set of contextual factors, such as the practice climate and leadership behaviors that influence the implementation and sustainability of the evidence-based practices (Riley et al., 2018; Titler and Anderson, 2019).

Implementation strategies that target the social context generally address infrastructure elements of the system (Riley et al., 2018). These strategies, described in the following sections, include

- Performing an environmental scan,

- Understanding the governance of the organization,

- Engaging with key leadership stakeholders,

- Addressing the standards of practice and documentation systems, and

- Promoting linkages among health systems and communities.

Environmental Scan

An environmental scan is a process that assesses internal strengths and challenges for a specific topic—in this case, the implementation of evidence-based practices. Environmental scans include the structure and function of the organization—how things are done within a system or community. One purpose of an environmental scan is to understand the mission, vision, and values of an organization and to articulate how the proposed evidence-based practices will contribute to meeting these organizational attributes. Those who lead the implementation

of evidence-based practices to address social isolation and loneliness will need to articulate how these recommendations will contribute to comprehensive care for the older adults served by the particular health system. (See Chapter 7 for more on comprehensive care.)

Organizational Governance and Engaging with Key Leadership Stakeholders

Understanding the governance structure is necessary so that work can be integrated into existing structures. Selected members of the implementation team will need to meet with key leadership stakeholders representing each of the disciplines that will be users of the evidence-based practices. Given the wide variety of health care workers who will be required to fully address social isolation and loneliness (see Chapter 8), it will be important for such meetings to include representatives across the health care workforce.

Addressing Standards of Practice and Documentation Systems

Written standards of practice (e.g., policies, procedures, clinical pathways) and documentation systems need to support the use of the evidence-based practices (Titler, 2010). Clinical information systems may need to be revised in order to support practice changes; documentation systems that fail to readily support the new practice thwart change (IOM, 2011b). For example, having an electronic health record or medical record that is capable of capturing data on social isolation and loneliness will be key to the implementation of Recommendation 7-3, the inclusion of social isolation in the electronic health record or medical record.

Promoting Linkages Among Health Systems and Communities

Several models of care delivery and role specialization have emerged to provide continuity and linkages across levels and sites of care delivery and with communities. These models include case management, care coordination, patient navigation programs, and transitional models of care (Hirschman et al., 2015; IOM, 2011b; Lamb and Newhouse, 2018; NASEM, 2016c; Naylor et al., 2013). People working within these models of care are key stakeholders to engage in implementing evidence-based practices and to provide linkages with the community. A care coordinator or patient navigator may be among the first to know if community-dwelling older adults are suffering from social isolation and can help navigate referrals and follow-up for community services to address the issue (see Chapter 8). These professionals are also well positioned to communicate the importance of this issue broadly among the health care workforce. To realize the full impact of implementing evidence-based practices within health care settings, it is essential to have partnerships and linkages with communities and those

outside the health sector (e.g., social services, law enforcement, urban planning and housing programs) (Brownson et al., 2018b; McMillen and Adams, 2018). To that end, Recommendation 9-1 calls for the integration of health care and social care in order to provide effective team-based care and promote the use of tailored community-based services to address social isolation and loneliness.

SUSTAINABILITY

As noted in Chapter 9, the sustainability of an intervention is a key element in the design and evaluation of that intervention. Sustainability refers to the degree to which the implemented evidence-based practices continue after implementation. Given the considerable effort and resources required to implement such practices, it is crucial to determine which improvements are sustained or decay following implementation. However, few studies have addressed the determinants of sustaining evidence-based practices following adoption (Stirman and Dearing, 2019). Experts agree, however, that planning for sustainability during development and delivery of implementation interventions contributes to sustainability and continued improvements (Ploeg et al., 2014; Shuman et al., 2018b; Stirman and Dearing, 2019; Tricco et al., 2016). The following principles are helpful to consider when planning implementation (Chambers et al., 2013; Colón-Emeric et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2019; Lennox et al., 2018; Ploeg et al., 2014; Shuman et al., 2018b; Stirman and Dearing, 2019; Titler et al., 2009; Tricco et al., 2016).

- Use implementation strategies that address the needs and context of the organization.

- Address alignment with the organization’s values, mission, and vision.

- Integrate evidence-based programs or practices into existing staffing models and workflow.

- Engage with key stakeholders early and often (stakeholder participation).

- Include programs for training new staff and conducting annual competencies of all staff.

- Plan for workforce turnover.

- With use of non-professional health workers such as lay health workers, plan for mechanisms to support their ability to deliver the evidence-based practices.

- Plan for and adapt to the dynamic contexts in which the evidence-based programs or interventions are implemented.

- Set boundaries for potential adaptations, including impact on outcomes.

- Include outcomes meaningful to the key stakeholders in evaluations, and share the findings.

- Incorporate selected metrics into quality and performance improvement programs for ongoing monitoring.

CONCLUSION

Promoting and sustaining use of evidence-based practices and programs is a dynamic process that is influenced by the context or setting, the population served, and the attributes of what is being implemented. The science of implementation is growing with multiple challenges and opportunities in advancing this field of inquiry. As the evidence base for effective interventions in health care settings for social isolation and loneliness in older adults is improved (as discussed in previous chapters), consideration of best practices for dissemination and implementation of this information is needed both in the planning of the intervention to be tested as well as in consideration of any implementation plan.

This page intentionally left blank.