Part II of the workshop began with a session exploring complex systems in society that provide the context for obesity and have the potential to shape population health and well-being. Shiriki Kumanyika, emerita professor of epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and research professor in the Department of Community Health & Prevention at the Dornsife School of Public Health, Drexel University, moderated the first half of the session, during which two speakers discussed power dynamics, structural racism, and relationships. Giselle Corbie-Smith, the Kenan Distinguished Professor and director of the Center for Health Equity Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, moderated the second half of the session, during which two additional speakers discussed resources, place-based issues, policy, and political will.

POWER DYNAMICS AND STRUCTURAL RACISM: INSIGHTS FROM CRITICAL RACE THEORY

Chandra Ford, associate professor of community health sciences and founding director of the Center for the Study of Racism, Social Justice & Health at the University of California, Los Angeles, discussed power dynamics and structural racism from the lens of critical race theory (CRT). She began by noting that she conducts her work on lands originally inhabited by the Tongva people, which, she said, shows that even those fighting for racial equity are complicit with and benefit from the historical and ongoing injustices to which indigenous peoples of the Americas have been subjected.

Ford began by drawing a parallel between systems science approaches, which help uncover complex relationships among systems that contribute to morbidity and mortality, and CRT, which she said draws on sophisticated conceptual and empirical approaches to identify and explain otherwise imperceptible racial drivers of inequities in society. She quoted Camara Jones’s (2000) definition of racism as “a system of structuring opportunity and assigning value based on the social interpretation of how one looks that unfairly disadvantages some individuals and communities, unfairly advantages other individuals and communities, and saps the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources.” According to Ford, nuanced forms of racism remain entrenched and effective at sustaining racial inequities.

CRT, Ford continued, originated with legal scholars of color in the late 1980s as a set of intellectual ideas, principles, and approaches to identifying, understanding, and undoing the root causes of racial hierarchies as they operate in the post–civil rights era. Critical race theorists ask how racism is relevant to a project, Ford explained, and to the production of knowledge about a problem. She highlighted several founding critical race theorists: Derrick Bell, who asserted that to address the less perceptible forms of racism, their mechanisms must first be made explicit through racism-conscious research; Kimberlé Crenshaw, who coined the term “inter-sectionality” to explain the presence of multiple overlapping, interacting social group identities (such as being both Black and low-income) that have synergistic effects on an individual’s risks and cannot be disentangled; and Cheryl Harris, who promulgated the concept of whiteness as property, which maintains that “holders” of whiteness have the same privileges and benefits accorded holders of other types of property. Ford briefly mentioned a model for applying CRT to the health sciences—Public Health Critical Race Praxis—which she described as an offshoot of CRT (Ford and Airhihenbuwa, 2010a,b, 2018).

Ford moved on to explain that models are imperfect representations of reality and that most systematically overlook the primacy of racialization. She suggested three ways in which CRT can help obesity-focused systems science approaches address these constraints. She cited first identifying and incorporating racism in mental models and analyses. Substantial evidence links racism to health, she maintained, and system dynamics models that include appropriate measures of racism could illuminate how structural racism contributes to obesity. She provided several resources1 for measuring racism at the individual, institutional, and socioecological levels, and urged measurement of race and ethnicity as social constructs. “Races” are not absolute entities, Ford asserted, elaborating that racialized groups exist relative to one another and that race is a differentiating trait that serves as a social mechanism for producing groups and hierarchies. She suggested that focusing on social construction indicates the importance of assessing (1) perceived versus self-reported race, noting that the latter might differ from identity; and (2) how gender, ethnicity, and other factors may inform both perceived and reported identity. She briefly noted that ethnicity is also a social construct and that strategies exist for measuring it as such.

Ford’s second suggestion for helping systems science approaches better represent reality was to address racialized power dynamics. She identified community-based participatory research as an approach that has encouraged equitable partnerships between researchers and communities as an

___________________

1 Racism: Science & Tools for the Public Health Professional. See https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/book/10.2105/9780875533049 (accessed September 11, 2020).

ethical and sustainable path to health equity. Power sharing will become more important in a systems science environment, Ford stressed, to the extent that the environment enables researchers to access more information about communities than communities can access themselves. Racism is embedded in some sources of big data, she argued, and big data may be used in ways that reinforce racial or ethnic marginalization (e.g., Benjamin, 2019; Noble, 2018). To illustrate this point, she observed that surveillance mechanisms disproportionately target people of color for criminal, social, and other forms of policing, and that systems may share data about individuals in communities without involving or seeking consent from those communities. She pointed out that social movements, such as Data for Black Lives,2 are emerging to challenge these practices, with the objectives of limiting surveillance of communities and democratizing access to data.

Ford’s third suggestion for improving systems science approaches was to address the social construction of knowledge. She elaborated by quoting sociologist Lawrence Bobo (2004): “Data never speak for themselves. It is the questions we pose (and those we fail to ask) as well as our theories, concepts, and ideas that bring a narrative and meaning to marginal distributions, correlations, regression coefficients, and statistics of all kinds.” Ford went on to note that although the scientific method enhances the reliability of empirical findings, it does not necessarily eliminate the influence of racial bias (Ford and Airhihenbuwa, 2018).

Ford suggested that researchers engage in “critical reflexivity” to assess how they may apply inadvertent subjectivity to their work. She explained this process by describing the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Testing, Linkage and Retention in care (HIV TLR) study (Ford et al., 2018). This 5-year retrospective cohort study linked multiple large datasets to electronic medical records, she explained, to examine contextual determinants of racial/ethnic disparities in outcomes along the HIV care continuum in Southern California. Each member of the study team completed a confidential questionnaire prior to each new arm, Ford explained, that assessed the member’s expected results, the level of certainty about each prediction, the nature of any expected disparities, and the basis for those expectations. The purpose of the questionnaire was to understand whether team members were inclined to endorse potential results that aligned with their a priori assumptions. According to Ford, the results indicated that raising people’s awareness of their biases and increasing the amount of time they have to respond to those biases may reduce the biases’ inadvertent effects.

Based on her broader experience in this area, Ford listed five questions that could potentially guide the next steps for applying systems science approaches to obesity efforts:

___________________

2 See https://d4bl.org (accessed October 9, 2020).

- What are best practices for sharing power with communities in a systems science approach?

- What racial biases are embedded in the data on which systems science approaches rely?

- How does the (uncritical) use of such data reinforce the marginalization of communities of color (e.g., via surveillance)?

- How might racialization/racism affect biological systems?

- To what extent are relational gains for the dominant racial group (i.e., Whites) obscured even in work on disparities?

Ford closed by stating that systems science approaches hold promise for tackling the complex phenomenon of obesity, and that these approaches can illuminate racism-related dimensions of the morbidity and mortality associated with obesity. Racism pervades every societal system, she maintained, although its greatest impacts are difficult to perceive, and she argued that CRT can help systems science approaches identify underlying racial drivers of obesity and associated inequities.

SOCIAL NETWORKS AND RELATIONSHIPS

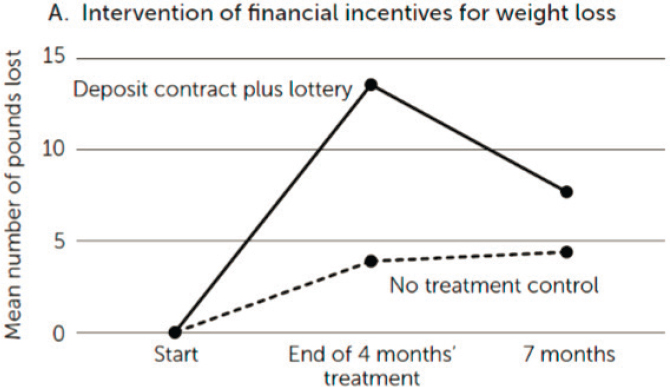

Kayla de la Haye, assistant professor of preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, prefaced her presentation on social networks and relationships by referencing the difficulty of changing eating and activity habits. A triangular relapse pattern is well known in obesity interventions, she said, whereby people who can access and adhere to evidence-based interventions often cannot sustain their initial modifications in lifestyle behaviors (see Figure 3-1). This pattern may occur, de la Haye explained, because people are able to exert personal agency, choice, and effort toward behavior change at the outset of an intervention, but they are not embedded in social and environmental structures that support healthful habits over the long term. She stressed that people with low incomes and communities of color are unequally exposed to structural influences that do not support healthful habits; therefore, interventions need to target multiple factors across layers of individual, social, physical, and macro-environmental systems that influence obesity risk.

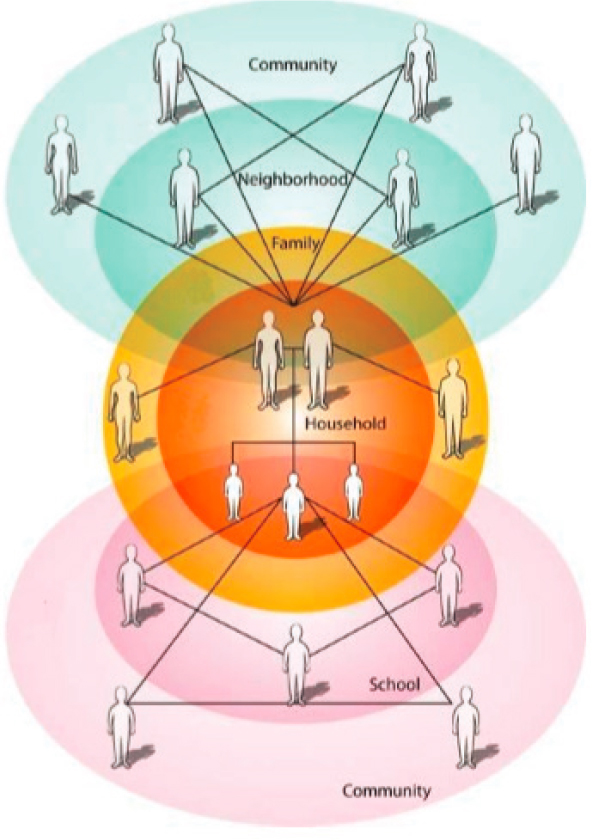

de la Haye suggested that much potential exists to leverage social environments, particularly the rich social networks that make up social fabrics, in systems science solutions for obesity. These include local social networks of family, friends, and community contacts that can influence obesity risk (see Figure 3-2), she elaborated, as well as global social networks of community members, stakeholders, and decision makers that shape the structural features of lived environments. She clarified her definition of “social networks” as denoting social structures comprising social actors and their

SOURCES: Presented by Kayla de la Haye, June 30, 2020. Wood and Neal, 2016.

interrelationships. These networks, she explained, transcend the online space and represent diverse types of relationships and social actors, such as kinship or friendship among community members; collaboration among organizations; or even partnerships among cities, states, and countries. She added that they are often illustrated with nodes representing social actors and with lines or ties between the nodes representing relationships that can have many different qualities.

Next, de la Haye described social network analysis, a broad theoretical and analytic framework used to study emergent patterns of actors and ties in a network, such as by identifying the occupants of knowledge-brokering positions that link disconnected communities and determining which social actors share close and clustered connections. As an example, she pointed to the use of social network analysis to study the racial and ethnic underpinnings of friendship network structures in high schools or the patterns of collaboration among different types of member organizations in a community coalition.

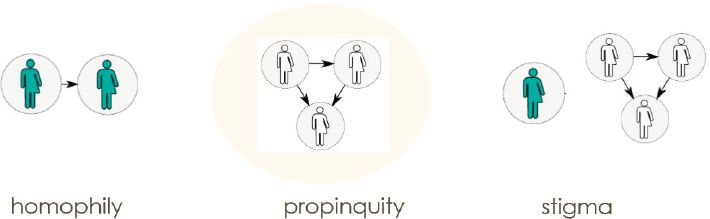

Social network analysis is also used to study the impact of social structures on individual and group outcomes, de la Haye continued, referencing research indicating that adults and children with obesity tend to cluster in social networks and that social connections with obesity increase a person’s obesity risk over time. She added that longitudinal research has linked these patterns to several contributing factors, which include homophily, propinquity, and stigma (see Figure 3-3). Homophily is a phenomenon whereby people tend to select or form social ties with others who have similar

SOURCES: Presented by Kayla de la Haye, June 30, 2020. Koehly and Loscalzo, 2009.

characteristics, de la Haye explained, such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or health risks and inequalities (Centola, 2011; de la Haye et al., 2011; Schaefer and Simpkins, 2014; Schaefer et al., 2011; Valente et al., 2009). Propinquity, she went on, refers to people connecting to others through shared social and physical spaces in homes, communities, and organizations, where structural and environmental influences are similar. Weight-based stigma is a third driver of these patterns of obesity in social networks, she

SOURCE: Presented by Kayla de la Haye, June 30, 2020.

said, explaining that people with obesity are often socially rejected by peers who do not have obesity. Over time, she continued, this phenomenon results in the formation of more social connections among individuals with similar weight status and marginalization of those who have overweight.

In addition to those three drivers, de la Haye explained, evidence indicates that social ties directly influence people’s weight norms and weight-related behaviors through a number of social influence mechanisms, which can lead to similarities in the risks for overweight among family members and friends (Aral and Nicolaides, 2017; de la Haye et al., 2011; Hammond et al., 2012; Simpkins et al., 2011; Trogdon et al., 2008; Valente et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2018). Resource support and social capital within networks can also impact obesity risk, she added, citing a study of the personal networks of Mexican American adults that found that having more health support in one’s personal social network predicted better diet quality, especially for people experiencing food insecurity (Flórez et al., 2020).3

Overall, de la Haye summarized, these dynamics of social selection, social influence, and corresponding shared exposures give rise to the clustering of obesity that researchers have observed in social networks. This observation highlights a critical feedback loop and intervention target, she pointed out, because people at high risk of developing obesity and impacted by inequities are more likely to find themselves in social networks that also confer health risks, and that influence and exacerbate people’s future risk for obesity.

In the final portion of her presentation, de la Haye shared examples of intervention approaches designed to leverage or change social networks as part of obesity solutions. She highlighted segmentation as one common strategy for local social networks, an approach that targets at-risk social groups (e.g., family or peer groups) rather than individuals for collective

___________________

3 See http://www.pfeffer.at/sunbelt/talks/1142.html (accessed December 1, 2020).

behavior change and as promoters of positive social influence, norms, and support for healthy habits (Valente, 2012). As a second strategy she cited alteration, in which an intervention aims to change people’s social networks by building new, adjacent health networks that can increase access to positive social influences, norms, and support (Valente, 2012).

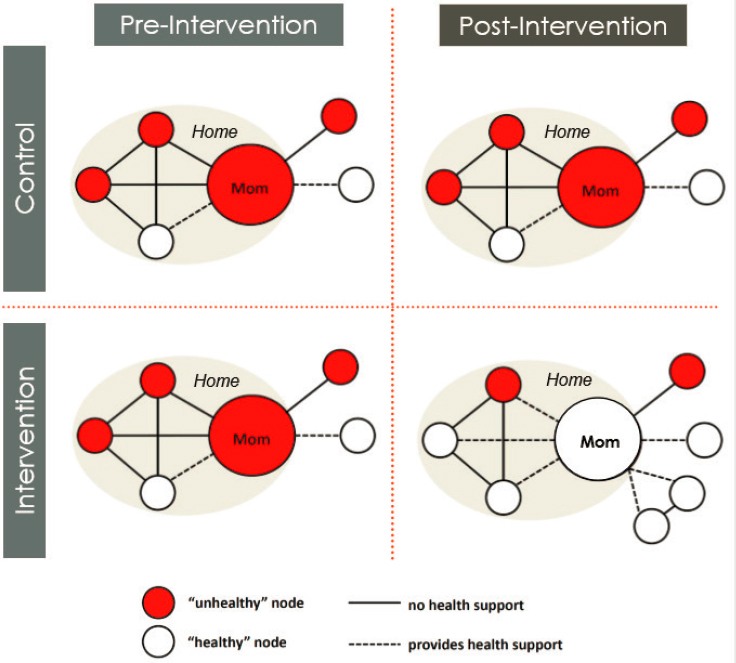

Next, de la Haye described the application of both segmentation and alteration in an intervention called Healthy Home, Healthy Habits that she and her colleagues designed and are evaluating (de la Haye et al., 2019). This intervention, she explained, aims to promote healthy dietary and activity habits for low-income mothers and their infants while simultaneously creating healthy changes in the home environment and creating new social ties among mothers in the program through group-based interventions and activities that seek to build meaningful and lasting social connections (see Figure 3-4). The intervention also connects mothers to community

SOURCE: Presented by Kayla de la Haye, June 30, 2020.

organizations that can support their families’ healthy habits, de la Haye added, which rounds out the intervention’s targeted social network changes. She described the overall goal of these changes as increasing social influence, social supports, and resources for healthy habits across mothers’ home and community settings.

To illustrate the role of social network strategies in changing global environments, policies, and broader systems—which she said are often shaped by networks of community members, organizations, and decision makers—de la Haye described research that mapped networks of collaboration among organizations in a community coalition tasked with creating whole-of-community changes to prevent childhood obesity (McGlashan et al., 2019). The research examined the structure of these collaboration networks, she recounted, and how their actions mapped to the risk factors that were identified in a community causal loop diagram. According to de la Haye, the exercise provided insights into and diagnostics for these networks during implementation, as well as a method for studying how the structure of these multilayer networks supported or hindered whole-of-community change.

Lastly, de la Haye highlighted the promise of diverse and novel data sources for providing insights into complex social systems and how they evolve and affect obesity solutions. She cited as examples of data that are emerging as valuable population-level signals of social structures and social mixing big data that are captured on smartphones, such as human mobility metrics, and network information that is visible in social media. She cautioned that certain voices, relationships, and social phenomena are likely to be privileged or hidden in different data sources. Finally, she suggested that the most powerful insights into social networks and their future role in obesity solutions will be drawn from the strengths of community partnerships, survey and interview data, and emerging sources of big data and secondary data.

PANEL DISCUSSION

Moderating a panel discussion following the presentations by Ford and de la Haye, Kumanyika began by asking the two speakers to comment on the direct relationship between the operation of racism and the operation of social networks and how both issues could be interrupted or restructured. In response, de la Haye explained that when researchers study the evolution and emergence of social networks, they often examine a rich set of variables that might predict the formation and maintenance of social ties and the exclusion of or discrimination against network members. Multiple features are often at play, she continued, and it is common to find that social selection and social mixing are based on race, ethnicity,

and socioeconomic status (and on gender in children), even more so than on obesity status. With respect to inequities and the concentration of health risks among certain populations, she added, these factors contribute to the social clustering and allocation of resources, to the segregation of certain populations in broader social networks, and to exposures to different types of social environments.

Ford postulated that critical race theorists would suggest considering the differences or similarities between stigmatization ties to racialization and stigmatization ties to obesity. She highlighted one of her research projects that analyzed networks with respect to various forms of discrimination against substance abusers, and reported that people who had experienced discrimination were more likely to form their own social groups and network ties. This phenomenon, she explained, reinforced the potential for HIV risk among people who had experienced discrimination, and she added that findings of this research differed by the level of residential racial segregation in which those networks existed.

Kumanyika next invited Ford to discuss implications of the use of data with respect to facial recognition algorithms and their interpretation or in other ways. Ford referenced anecdotal evidence suggesting that health care vendors believe certain characteristics are associated with appointment truancy, and their integration of those characteristics into appointment scheduling algorithms results in longer wait times for patients with those characteristics. According to Ford, the types of general issues that will emerge from the use of big data, let alone the potential racial or racism-related issues, are not yet fully understood. Partnerships with communities are an important safeguard to facilitate the appropriate use of big data, she asserted, by ensuring transparency and access so that people understand what information is available and can drive and monitor the kinds of data that are collected. As an example of this point, she pointed to policing-related surveillance tools, which she said are developed and directed to point toward existing/prevalent or expected crime. She added that different types of tools would be needed to examine the causes of crime and to understand how analysis results derived from surveillance tools may be influenced by the person who is doing the surveillance. She added that racial justice advocates are asking these kinds of questions with regard to big data content and ownership.

Kumanyika next asked the two speakers to comment on whether efforts to help people avoid discrimination or exclusion, including in the methods used to analyze data in relation to racism and social networks as systems, are not really working against human tendencies (e.g., inclinations toward ethnocentrism and pecking orders). In response, de la Haye flagged this possibility as a potential intervention point, elaborating that researchers identify new intervention points as they gain understanding of social and

network dynamics, such as the role of weight-based stigma and discrimination in network structuring. She added that the social network literature has increasingly used the concept of contagion to describe the spread of beliefs and behaviors through networks, which has highlighted that concept as a potential intervention point.

Ford remarked on the apparent parallels between systems thinking and CRT in terms of their aims to study a topic systematically, using various tools to uncover underlying, complex relationships. She expressed optimism about the promise of systems science approaches as applied to obesity solutions.

AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Following the panel discussion, Ford and de la Haye addressed workshop participants’ questions about promoting breastfeeding as a strategy for preventing obesity, countering homophily to address obesity and other health concerns, measuring race as a social construct, addressing systemic bias favoring biological causes, and addressing structural racism while influencing systems.

Promoting Breastfeeding as a Strategy for Preventing Obesity

A workshop participant asked about promoting breastfeeding as a strategy for preventing obesity and incorporating race and racism in breastfeeding interventions. In response, de la Haye commented that some interventions aimed at preventing obesity in the first few years of life have included breastfeeding as one component. Promotoras and other community-based partners, she explained, have delivered such interventions within family systems and provided insight into relevant family beliefs and cultural factors influencing breastfeeding. She identified as an emerging area of study how breastfeeding behaviors are influenced by different sources of information and influences within social networks. Kumanyika agreed with the importance of examining systems that may drive the historically lower rates of exclusive and long-duration breastfeeding among Black women.

Countering Homophily to Address Obesity and Other Health Outcomes

A workshop participant asked about the desirability of proactively countering homophily in networks to address obesity and other health outcomes. In response, de la Haye said that countering homophily is an interesting intervention strategy because humans have evolved to connect with people with whom they can communicate and relate. People often seek out others who speak the same language, she elaborated, and feel a

connection with others who share a similar background. She reported that, according to her research, stigma is a key force driving the homophily observed in health networks, such that people with selected characteristics (e.g., obesity) and health attributes are actively excluded from certain relationships. Interventions aimed at addressing stigma and discrimination, she argued, can help reduce this marginalization of certain individuals and their segregation into homophilous segments of a social network. Ford suggested that critical race analysis would pinpoint the inequality in the stigmatization of obesity (or other health condition) as the problem, rather than the homophily resulting from it.

Measuring Race as a Social Construct

Ford responded to a workshop participant’s question about how to measure race as a social construct in research settings. A first step, she offered, is to anchor race to a specific project to see how racism’s operation is tied to, for instance, the experience people have when they are walking down the street and how others perceive them. She added that although the self-reported experience of racism is often held up as the ideal measure of race, how one’s race is perceived by others would provide a better measure of the social experience of racism in that circumstance.

Addressing Systemic Bias Favoring Biological Causes

Another workshop participant alleged a fundamental bias in favor of biomedical research, maintaining that despite evidence and recognition of social constructs such as race, people continue to espouse essential-ism, according to which causes are at least partially biological rather than socially constructed. In response, Ford cited a lack of investment in studying the subjectivities that researchers bring to their work. She suggested that researchers regularly fill gaps in their results with their a priori assumptions. More study would be helpful, she argued, to reveal empirically the extent to which researchers do or do not reify biologically deterministic understandings of race. This process could be supported by Public Health Critical Race Praxis, which she reminded participants is intended to facilitate the application of critical race principles and methods to public health research approaches.

Addressing Structural Racism While Influencing Systems

A workshop participant asked for examples of methods that organizations like the Roundtable on Obesity Solutions can use to address structural racism when attempting to influence complex systems. In response, de la

Haye suggested that such methods as social network analysis can provide insight beyond the perspective of individual experiences to highlight how phenomena like structural racism operate and structure people’s experiences, exposures, and health risks. Ford emphasized the importance of calling racism by its name and discussing it openly. She encouraged examination of how researchers understand structural racism and how that understanding manifests in their work, as well as how structural racism operates in society and relationships.

Kumanyika stated that the process of calling out racism and understanding potentially counterproductive characteristics of social networks involves both people who are in positions of power and people who are not. She invited the speakers to suggest next steps for engaging those who have power and who benefit from structural racism or homophilic behavior that excludes others. Ford reminded workshop participants that race is a relational construct in that it has meaning when one is comparing racial groups and understanding how one group gains from another. She reiterated that it is important to avoid treating this disadvantage as an attribute of the minority population, and advocated instead for capturing it as one of the gains of the dominant group.

The importance of considering who conducts the research and collects and uses the data was stressed by de la Haye. She highlighted the focus of systems science approaches on teams that are multisector and multidisciplinary and involve and equally privilege views of community partners and other stakeholders. That inclusion is critical to understanding the data that are collected and privileged, she argued, and it is also key to promoting practices of data analysis and interpretation that can illuminate social phenomena and provide opportunities to address them.

THE IMPACT OF NEIGHBORHOOD ENVIRONMENTS ON HEALTH

Ana Diez Roux, dean and the Distinguished University Professor of Epidemiology in the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel University, discussed the impact of environmental factors, particularly neighborhood characteristics, on health. She explained that neighborhoods are important contexts for physical and social exposures and can supplement individual-based explanations for health behaviors and outcomes. She also suggested that neighborhood differences may be important contributors to health inequities and that they have major public health and policy relevance because of the strong neighborhood segregation by race and income in U.S. society.

Diez Roux stressed that identifying causal effects of neighborhoods is complex because many factors drive neighborhood differences in health.

Examples of these factors include neighborhood features (e.g., availability of places to be physically active) and the sorting of people into neighborhoods based on individual attributes (e.g., people with lower incomes live in neighborhoods with fewer resources for physical activity). According to Diez Roux, much of the traditional empirical work on neighborhoods and health has attempted to disentangle the effects of a neighborhood’s context from the effects of its residents’ attributes in order to understand the impact of each, which she explained would help reveal causal effects. She argued, however, that the issue is much more complex because some people may be able to select where they live based on preferences for certain attributes (such as resources for physical activity), and some people may change their behavior in response to that of others around them. Furthermore, she added, neighborhoods themselves can change in response to residents’ behaviors; for example, the presence of a high proportion of physically active residents may attract proprietors of recreational resources to locate in those neighborhoods. Ultimately, Diez Roux asserted, these processes form a system in which individuals and their environments evolve and interact over time to produce the neighborhood patterns that emerge, and she added that neighborhoods also affect each other.

In the face of this complexity, Diez Roux continued, interest abounds in applying systems science approaches, particularly agent-based modeling, to neighborhood effects research. According to Diez Roux and her colleagues, one reason these approaches are suitable for this research is their utility for better understanding the bidirectional person–environment relations that occur in neighborhoods, such as selection and endogeneity (e.g., understanding whether neighborhood physical activity levels increased because of local zoning and land use changes, or physically active people were more likely to move to the neighborhood because the changes made it more activity-friendly) (Auchincloss and Diez Roux, 2008). Other reasons for applying systems science approaches to this research, she added, are to better understand interactions among people, interactions and interrelations between physical and social environments, and spatial patterning (i.e., segregation) of individual and environmental characteristics.

Diez Roux highlighted research applying a particular systems science method, agent-based modeling, to explore drivers of income inequalities in diet in the context of residential segregation (Auchincloss et al., 2011). For background, she stated that income differences in dietary behaviors are well established as potential contributors to health disparities, and that spatial segregation of access to healthy food has also been documented (e.g., certain stores do not locate in lower-income neighborhoods). However, she said that questions remain regarding causality and policy implications.

According to Diez Roux, the model developed for this research was designed to address two questions. The first was whether spatial segregation

contributes to income disparities in diet absent price or preference differentials, because, Diez Roux explained, it has been argued that neighborhoods simply offer what residents demand. The model was used to investigate whether the spatial segregation of stores was sufficient to generate income inequalities in diet, she elaborated, if price and preference differentials were eliminated. The second question that the model was used to address, she continued, was the degree to which price and preference manipulations affect disparities in dietary behaviors.

Diez Roux went on to explain that the two types of agents in the model are households and stores, which each have individual attributes and behaviors. She pointed out, for example, that people shop based on distance and prices, and stores react to the volume of shoppers. To address the first of the above questions, Diez Roux continued, the model compared income differentials in diet under various spatial segregation scenarios, assuming no differences between healthy and unhealthy foods in either price or preferences. It then compared income differentials holding spatial segregation constant but varying price and preferences. According to Diez Roux, the model tested different hypothetical segregation scenarios in which people with lower incomes were clustered with unhealthy stores or vice versa to see which scenario produced income differentials in diet comparable to real-world observations.

Diez Roux reported that the researchers identified a scenario most likely to result in people with higher incomes having healthier diets relative to people with lower incomes. In this scenario, lower-income households were clustered with unhealthy food stores and high-income households with healthy food stores. This result led the team to conclude that income differentials emerge in the presence of co-segregation of lower-income residents and unhealthy food stores (or higher-income residents and healthy food stores), even when food price and preferences are constant. The model then explored the effects of manipulating preferences, Diez Roux continued, such as convincing all residents to prefer healthy food. Even then, she reported, preferences could not overcome the spatial inequities, and the income differentials in dietary behaviors persisted. She added that when the model manipulated price to make healthy foods less expensive than unhealthy foods, lower-income households had better diet quality (e.g., preference for whole grains and fresh vegetables versus preference for energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods) compared with high-income households. Diez Roux remarked that this simulated outcome occurred because the relatively more expensive, unhealthy food stores closed in lower-income neighborhoods, which increased those neighborhoods’ access to healthy foods.

Ultimately, Diez Roux said, the model simulation enabled the research team to conclude that segregation can create disparities in diet even if differences in price and preferences do not exist, and that changing preferences

is not enough to eliminate those disparities. Price manipulation appears to have a stronger impact than that of preference manipulation, she noted, but price and preferences reinforce each other. She emphasized that the modeling exercise compelled the team to consider the processes through which dietary disparities arise, which helped generate ideas for new data collection (e.g., such variables as shopping behavior and store dynamics) and empirical analyses to fill research gaps.

Diez Roux summarized the benefits of modeling approaches, reiterating that they oblige researchers to develop dynamic conceptual models with which to illuminate mechanisms that generate associations rather than focusing on separate independent effects, account explicitly for the interrelatedness of people and environments, and allow for input from various stakeholders. Modeling tools can yield insight through simulation, she added, and thought experiments can evaluate the effects of hypothetical interventions in a systems context.

Diez Roux next outlined caveats regarding modeling approaches. First, she advocated for “keeping it simple, but relevant.” Second, she stressed that establishing transparent inclusion criteria for a model’s elements is critical, as is producing data with which to support a model’s assumptions, calibrate its parameters, and validate it. Developing and refining a model is an arduous process, she acknowledged, during which transparency and communication can be a challenge. Finally, she declared that a model’s outputs reflect the degree of effort invested in creating it.

Diez Roux moved on to describe how systems science approaches prompt users to rethink their research questions. This may be the most valuable aspect of a systems science approach, she speculated, and she shared an example of transforming a relatively limited research question into a more nuanced, policy-relevant question:

Diez Roux proposed that the toolkit for generating knowledge and evidence about population health includes modeling, observation, experimentation, action, and evaluation of action as methods that reinforce and feed back into each other. More complete understanding can be gained by combining these approaches, she argued, and by using them to quadrangulate across different methods.

Diez Roux closed her presentation by describing the SALURBAL (Salud Urbana en America Latina) study, which focused on urban environments in Latin America and health equity (Quistberg et al., 2018). She explained that one of the study’s aims was to evaluate urbanicity–health–environment links and plausible policy impacts using systems thinking and simulation modeling methods, which included a participatory group model-building exercise. She described this method as engaging multiple stakeholders in building systems maps of a particular problem or process, informed by the stakeholders’ lived experiences, professional backgrounds, and individual knowledge and experience. A group develops a causal loop diagram to illustrate the system, she continued, and uses it to identify critical factors as potential intervention targets and mechanisms; she added that these maps may also inform subsequent agent-based modeling.

Diex Roux ended her presentation with a quote from epidemiologist Raoul Stallones: “If we consider disease to be embedded in a complex network in which biologic, social, and physical factors all interact, then we are impelled to develop new models and adopt different analytic methods.”

INTERSECTION OF POLICY AND SYSTEMS SCIENCE MODELING TO EXAMINE SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND OBESITY

Tiffany M. Powell-Wiley, Earl Stadtman tenure-track investigator at the National Institutes of Health and chief of the Social Determinants of Obesity and Cardiovascular Risk Laboratory, discussed the intersection of policy and systems science modeling in the context of social determinants of physical activity and obesity. She referenced the association of obesity and diabetes with premature mortality from cardiovascular disease in the United States, noting that non-Hispanic Black populations are disproportionately affected. Ideally, she suggested, interventions to address these disparities will target health behaviors related to obesity, promote health equity, and account for the social environment (Ceasar et al., 2020).

Powell-Wiley enumerated key components of her work on the relationship between cardiometabolic risk and neighborhood social environments, including perceptions of the environment and such factors as crime and safety. She also highlighted community engagement, a process in which communities help define their vision of health and suggest potential interventions, and review of epidemiologic studies, which help researchers determine how to extend the findings of community-engaged work. Systems science approaches such as simulation modeling help bridge the first two components, she explained, to support the development of interventions that account for the complexity of how social environments relate to obesity and other cardiovascular risk factors.

Powell-Wiley described how these components played out in her group’s work with the Washington, DC, Cardiovascular Health and Obesity Collaborative, which she said is built on engaging communities through a community advisory board of multidisciplinary church and community leaders dedicated to addressing cardiovascular health. The board facilitates community engagement and provides input for the development and design of research projects, she explained, such as the collaborative’s first project, the Washington, DC, Cardiovascular Health and Needs Assessment.

Powell-Wiley highlighted the assessment’s use of principles of community-based participatory research, describing how researchers gathered data at community sites and used mixed methods to evaluate environmental and psychosocial factors related to cardiovascular risk and potential intervention tools. The assessment found that physical activity could serve as a target for improving cardiovascular health in the city’s Wards 5, 7, and 8, Powell-Wiley reported, and showed the feasibility of using mobile health technology to develop a physical activity intervention. Results also indicated that community members perceived crime and limited safety as barriers to physical activity.

Powell-Wiley recounted that her group then reviewed epidemiologic studies in an attempt to extend the findings of the community-engaged work. After examining data on crime, safety, and change in cardiometabolic risk from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis cohort, the researchers found an association between a greater decrease in safety over time and a greater increase in adiposity, but not a clear relationship between objective crime and adiposity (Powell-Wiley et al., 2017a). According to Powell-Wiley, this finding illuminated the concept of increased perceived safety as a potential target for intervention, which could both increase physical activity and account for residents’ concerns about crime and safety.

Powell-Wiley next described the intervention’s use of agent-based modeling to simulate intervention effects on community members. She explained that this method facilitates exploration of how individuals within the community interact with each other and with their environments, as well as how those relationships and environmental changes affect the system as a whole (Hammond, 2009; Nianogo and Onyebuchi, 2015). The simulation examined the impact of crime on physical activity and obesity among Black women from 80,000 households in Wards 5, 7, and 8, Powell-Wiley recalled, and community assessment data were used to validate the model. As an individual’s propensity to exercise increased, reductions in crime that increased the accessibility of locations for physical activity were associated with a greater decrease in the prevalence of obesity, which she suggested showed the importance of multilevel approaches to reducing crime in order to increase leisure-time physical activity and reduce obesity (Powell-Wiley et al., 2017b). She offered as an example targeting crime through urban

renewal policies so as to improve perceived safety in resource-limited urban communities.

Powell-Wiley observed that the term “urban renewal” often evokes such concepts as gentrification, which she said may have negative consequences for health equity. She shared the example of an urban renewal process with a health equity focus that is under way in Ward 8, highlighting its community economic development planning process, which engages both community residents and research partners (Mustafa, 2020). The researchers can advise community-driven efforts, she said, such as by conducting asset mapping to identify economic development opportunities that can meet community members’ needs. Powell-Wiley added that in the future, her research group will be developing and using agent-based models to test multilevel mobile health interventions for promoting physical activity, and may also be testing how crime may limit the intervention.

Lastly, Powell-Wiley encouraged use of a health equity framework to guide the development of interventions focused on health promotion and health behavior change (Kumanyika, 2019). This framework, she explained, suggests four focus areas—increase healthy options, reduce deterrents, improve social and economic resources, and build on community capacity—to address when pursuing health equity for obesity prevention.

PANEL AND AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Corbie-Smith moderated a discussion with Diez Roux and Powell-Wiley following their presentations. She began by asking the two speakers how their systems science approaches can help build political will for structural changes to address obesity. Diez Roux replied that it has been noted that systems science approaches featuring modeling can help elucidate situations in which there is resistance to policy and in which the effects of policy are the opposite of what is intended, such as magnifying instead of reducing health equity. She argued that modeling can help stakeholders understand why those results occur and what changes could be made for policy to have its intended effect, adding that modeling can also help identify new leverage points for policies. According to Powell-Wiley, opportunity exists to build momentum for policy change by engaging community leaders in model building and use so they can visualize the potential results of different policy options.

Corbie-Smith then asked the two speakers questions submitted by workshop participants. Those questions addressed the impact of policing on community safety and physical activity, the study of systems of advantage in highly segregated White communities, and the use of models to examine the dynamics of structural racism.

Impact of Policing in Communities

The speakers were first asked whether their research had examined the impact of policing versus other neighborhood development investment approaches. Powell-Wiley reported that her team has considered building a model to explore the impact of community policing in neighborhoods targeted by their research. She also replied to a follow-up question about nonpolicing strategies for increasing safety to increase physical activity by sharing that her team would like to study how community policing or even “violence interrupters” (i.e., individuals in the community who try to prevent escalations of violence) might impact physical activity and obesity.

Study of Systems of Advantage in Highly Segregated White Communities

Next, Diez Roux responded to the question of whether systems of advantage, such as community investment, in highly segregated White communities have been compared with circumstances in communities where there may have been disinvestment or no investment. She suggested that systems science approaches are well suited to addressing this type of question because they can be used to explore the dynamics that occur and drive health differences, such as those by which the segregation of White advantaged residents results in certain businesses locating or not locating nearby. Systems thinking is critical for understanding drivers of health inequities, she maintained, and for understanding how structural racism affects health.

Using Models to Examine Dynamics of Structural Racism

Powell-Wiley shared an example of her team’s thinking about discrimination and segregation and their relationship to decision making about physical activity. The team considered how Black women may feel less comfortable engaging in physical activity if the people around them look different, she explained, or more comfortable if the people around them look similar. She suggested that this comfort level might affect physical activity preferences or the likelihood of engaging in physical activity, which are factors involved in this decision making.

Diez Roux argued that structural racism affects neighborhoods through the multifaceted ways in which it drives residential location. This phenomenon is related to historical redlining, she asserted, and to history that leads to differences in resources where people live. She suggested that the concentration of certain kinds of people in an area has consequences for the area (such as the location of businesses and the role of the police) as a result of institutional racism, which reinforces segregation and health inequities.

This page intentionally left blank.