1

Introduction

A growing number of prescription drugs, including some of the most expensive ones, are dispensed in variable doses that are administered based on a patient’s weight or body surface area (BSA) rather than in fixed or flat doses. Fixed or flat doses of prescription drugs are familiar to patients who have taken antibiotics, pain medications, cholesterol-lowering drugs, and other medications in pill or tablet form; by contrast, many cancer drugs are administered by weight. Such medications have no such thing as a standard dose. Instead, each patient receives a personalized dose based on his or her weight or body size. Because of safety considerations, the typical approach in the United States is to package these medications in single-dose vials that are intended for use by a single patient. This leads to a situation that has been seen by many as a major concern: discarded drugs. Single-dose vials come only in a limited number of specific sizes,1 so the amount of the drug contained within a vial often exceeds the required weight-based dosage2 for a given patient, and whatever amount is left over will be discarded. In some cases, that is a significant percentage of the vial. This situation has garnered a great deal of attention because a simple calculation, multiplying the nominal per-milliliter cost of these drugs by the number of milliliters discarded

___________________

1 The phrase “vial size” used throughout this report refers to the volume per vial of a drug.

2 Hereafter, the committee uses weight-based dosing to refer to drug dosing based on measures of “body size,” including dosing based on either weight or BSA, which is closely correlated with body weight. Although these two approaches can be distinguished and justified clinically, for the purposes of this report, both are considered under the single phrase “weight-based.”

each year, yields an apparent result of a value in the billions of dollars. The natural question becomes whether it could be possible to save billions of dollars per year by finding a way to avoid discarding these drugs.

STUDY CHARGE

In light of this issue and others related to discarded drugs, the U.S. Congress mandated that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) should enter into an agreement with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) “to conduct a study on the federal health care costs, safety, and quality concerns associated with discarded drugs that result from weight-based dosing of medicines contained in single-dose vials.”3 The National Academies appointed the Committee on Implications of Discarded Weight-Based Drugs to carry out this task. The full Statement of Task for the committee is presented in Box 1-1.

In addition to the study’s formal Statement of Task, CMS required the committee to address some key items as they relate to the Statement of Task.

- Provide a comprehensive assessment of federal health care costs, to both the Medicare program and to Medicare beneficiaries, due to billing for wasted drugs and biologicals from single-dose vials.

- Using available data sources, quantify the amount of waste associated with single-dose injectable drugs and biologics in billing units and/or proportion of available vial sizes and calculate the associated dollar amounts.

- Identify relevant drugs, vial sizes, dosing practices, and delivery practices most associated with waste.

- Evaluate dosing strategies that may contribute to or mitigate excessive drug waste where possible (e.g., dosing based on weight, BSA, and institutional rounding/dose capping protocols).

- Investigate manufacturer rationale for developing particular vial sizes and safety standards (such as those from the United States Pharmacopoeia) influencing requirements for single-dose versus multi-dose vial development and use.

Although the committee acknowledges the importance of discarded drugs as it pertains to other drugs—including outpatient prescription

___________________

3 See Committee on Appropriations bill (S. 3040) for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2017. See https://www.congress.gov/114/crpt/srpt274/CRPT-114srpt274.pdf (accessed August 31, 2020).

drugs covered under Medicare Part D that are oral or self-administered—this report focuses on weight-based, single-dose vials covered under Medicare Part B, which are typically administered by clinicians in physician offices and hospitals’ outpatient departments by infusion or injection. This report and its conclusions may be relevant to situations in which private health insurance payers use similar methods to reimburse providers for drug administration, but the charge limits the committee’s purview to federal programs.

COMMITTEE’S APPROACH

The study committee contained individuals with various areas of expertise, including public health, health care access and affordability, health economics and finance, health care delivery, health care services research, pharmacy, federal health care payment policy, ethics and health care policy, drug manufacturing and packaging, oncology, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversight, and private health insurance. (See Appendix D for the biographical information on the committee and staff.) The committee conducted an extensive review of the literature pertaining to this topic, supplementing it with a variety of sources—including three public information-gathering sessions and written comments from

interested stakeholders. The committee also commissioned two analyses: one examining Medicare data intended to help the committee better understand the financial burden of discarded weight-based drugs for the Medicare program and the other examining MarketScan claims linked to Health Risk Assessment data, to help the committee to better understand the financial burden of discarded weight-based drugs for payers and patients in the private health insurance market. The committee also drew on the 2018 National Academies report Making Medicines Affordable: A National Imperative (NASEM, 2018).

In this report, the committee uses the phrase single-dose vials to refer to drug vials that contain approximately one dose and are intended to be used a single time for a single patient. The committee recognizes that single-dose vials and single-use vials have been commonly used interchangeably in the literature to mean vials that contain drugs for a single patient. The use of single-dose vial is consistent with the approach taken from FDA (2018). The committee uses multiple-dose vial to refer to any vial that contains more than one dose of a drug and is intended to be administered multiple times, to either the same or different patients. In 2018, FDA began using a new phrase, single-patient-use vial, to describe a vial that contains multiple doses of an injectable medical product and is intended to be used in a single patient (FDA, 2018). The committee chose not to use this label, preferring to employ multiple-dose vial for any vial that contains more than one dose of a drug and is intended to be administered multiple times; because the focus of this report is on single-dose vials, the committee saw little utility in introducing an additional term to distinguish between types of multiple-dose vials.

The committee uses weight-based dosing to refer to drug dosing based on measures of “body size,” including based on either weight or BSA, which is closely correlated with body weight. The committee recognizes that weight-based dosing has been used at times in slightly different senses in the literature. Dosage adjustment in children is not addressed in this report, in light of its focus on Medicare Part B. However, the findings and recommendations of this report may well be used by policy makers and the health care industry beyond Medicare Part B.

Additionally, while the main focus of the report is on Medicare Part B, which involves primarily administered and injected drugs, not drugs for which the physician typically writes a “prescription” for a drug to be directly acquired by the patient, this report uses the term prescription drugs in a broader sense to indicate all drugs whose use is directed by a physician.

CONTEXT OF RISING HEALTH CARE COSTS

The issue of discarded weight-based drugs from single-dose vials takes place in the larger context of concerns about skyrocketing drug prices and, more generally, about the high cost of health care in the United States. Making Medicines Affordable documented that Americans spend, on average, twice as much on health care as people in other high-income countries. Currently, approximately 18 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) is spent on health care—a portion that is significantly greater than any other country in the world (NASEM, 2018; Papanicolas et al., 2018).

However, despite this high health care spending, the health of Americans is not noticeably better than that of people living in other wealthy nations, and by many measures it is worse (Papanicolas et al., 2018). For example, according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Global Health Observatory data, when countries are ranked by life expectancy, the United States is only 34th on the list, behind several middle-income countries (WHO, 2020). Much of the greater life expectancy in other countries can be attributed to evidence that individuals in other high-income countries tend to have healthier lifestyles than Americans and that these countries generally place greater emphasis on public health practices and social needs—an indication that most other countries are getting a much greater return on their health care spending, in terms of the citizen health, than the United States is (Papanicolas et al., 2018). Furthermore, because the United States is projected to have a steadily aging population over the coming decades, it seems likely that the percentage of GDP spent on health care will continue to increase for the foreseeable future unless some fundamental changes are made in the health care system (NASEM, 2018).

Prescription Drug Expenditures

Many factors contribute to the high costs of U.S. health care, but spending on prescription drugs is a major component of the problem. Making Medicines Affordable (NASEM, 2018) described the steady rise in the cost of prescription drugs that has taken place in the United States over the past few decades and discussed the reasons for that rise. As of 2016, prescription drugs accounted for approximately 17 percent of the total cost of U.S. health care services (Kesselheim et al., 2016), and such drugs have been—and continue to be—significant for the increasing health care costs.

In particular, specialty drugs have played a major role in the rapidly rising costs of drugs. Many specialty drugs (which include weight-based

injectable and infused drugs) are used for treating different types of cancers and diseases of older persons and are administered in a physician’s office or hospital (Lotvin et al., 2014). Currently, while specialty drugs comprise only about 2 percent of the prescriptions written annually in the United States, they account for about one-half of the total U.S. drug spending (IQVIA, 2019).

Given the rapidly rising costs of prescription drugs in the United States, the significant part of overall health care spending that they represent, and the fact that Americans pay so much more for prescription drugs than those in other countries (Kanavos et al., 2013; Sarnak et al., 2017), steps to lower drug costs or slow the increases in those costs could be an important part of the solution to the broader problem of rising health care costs. It was against this backdrop that the committee took on the task of determining whether efforts to reduce “waste” associated with discarded drugs resulting from weight-based dosing of drugs contained in single-dose vials, or to increase efficiency in the dispensing of such drugs, holds promise in that broad effort.

Medicare Part B

The U.S. government has health care programs that serve older persons, persons with disabilities, low-income individuals, veterans, active-duty military personnel and their dependents, and Native Americans. The populations these programs serve, the types of health care services they cover, and, specifically, their prescription drug coverage influence the trends in drug use and spending across these programs. Medicare Part A covers inpatient hospital costs, whereas Part B covers outpatient care and certain drugs—primarily infusible and injectable drugs and biologics—if they are administered in physician’s offices and hospital outpatient departments and certain other drugs provided by pharmacies and suppliers. Medicare Part B also covers some outpatient prescription drugs, mainly certain oral cancer and antiemetic drugs that are exact replacements for covered infusible drugs (ASPE, 2020). Medicare Part D covers most outpatient prescription drugs, which patients typically administer themselves.

In Medicare Part B, the health care provider or facility (clinic, physician office, or hospital) buys drugs directly from manufacturers or from intermediaries such as wholesalers or specialty pharmacies, stores them in its practices, and administers them to a patient as needed. The health care provider then submits a claim to either Medicare or the patients’ health insurance for reimbursement. The Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) of 2003 changed Medicare’s payment methodology for drugs covered by Part B from an average wholesale-price-based approach to a market-based

price approach, which is based on the drug’s average sales price (ASP) plus a percentage add-on for administering the drug.4 The ASP is computed using the manufacturer’s unit sales of a drug to all U.S. purchasers submitted to CMS in a calendar quarter divided by the number of units sold, minus all price concessions, such as volume discounts, cash discounts, and rebates. Under the budget sequestration cuts, payments to health care providers for most Part B drugs were changed from the ASP plus 6 percent to the ASP plus 4.3 percent (Werble, 2017).

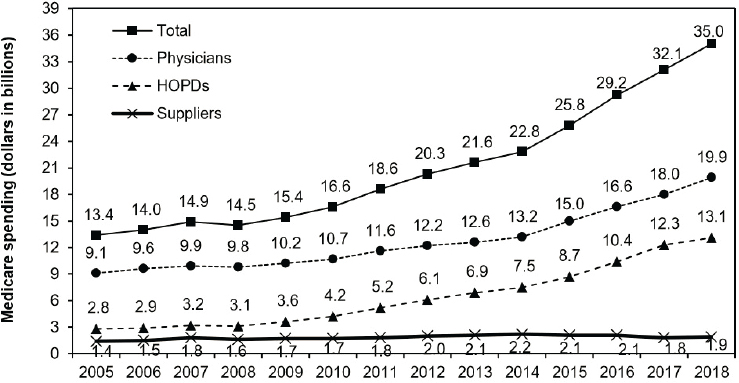

Drug spending has been growing more rapidly in the Medicare Part B program than in any other federal health care program (ASPE, 2020). In 2020, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), an independent commission established to advise Congress on issues affecting the Medicare program, released a report that included an analysis of Medicare Part B spending from 2005 to 2018 (MedPAC, 2020). While these data were not adjusted for inflation or the number of enrollees, the analysis found that spending on Medicare Part B drugs increased from $13.4 billion in 2005 to $35 billion in 2018, for an average annual growth rate of 7.7 percent (see Figure 1-1). Physician offices accounted for 57 percent ($19.9 billion) of the total Medicare Part B drug spending in 2018. Hospital outpatient departments accounted for 38 percent ($13.1 billion), and suppliers—including retail pharmacies that supply classes of oral drugs covered under Part B—accounted for 5 percent ($1.9 billion).

A relatively small number of drugs, most of which are specialty drugs, accounts for a substantial share of Part B spending (ASPE, 2020; GAO, 2015). In 2018 the 10 highest-cost drugs, which mainly treat cancer, macular degeneration, and immune-mediated diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, accounted for $12.2 billion in Part B payments (not including beneficiary cost-sharing), or 46 percent of the $26.6 billion in total Part B spending for all drugs (ASPE, 2020).

Traditional fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries pay 20 percent of the Medicare-approved amount for covered Part B prescription drugs (CMS, 2020). Approximately 81 percent of these beneficiaries have supplemental health insurance or drug coverage that is purchased separately, comes from Medicaid, or comes from prior employers (Cubanski et al., 2019). The remaining 19 percent who have no supplemental coverage pay 20 percent coinsurance for Part B drugs, with no cap on annual total-out-of-pocket expenses. The committee recognizes that not all Medicare beneficiaries will use Part B drugs, and most of them have supplemental coverage. However, the way Part B drugs are acquired and paid for places a significant out-of-pocket burden on those who do need Part B drugs

___________________

4 See https://www.congress.gov/bill/108th-congress/house-bill/1 (accessed September 23, 2020).

NOTES: Data include Part B–covered drugs furnished by several provider types including physicians, suppliers, and hospital outpatient departments, and exclude those furnished by critical access hospitals, Maryland hospitals, and dialysis facilities. “Medicare spending” includes program payments and beneficiary cost-sharing. Data reflect all Part B drugs whether they were paid for based on the ASP plus 6 percent or another payment formula. Data exclude blood and blood products (other than clotting factor). Components may not sum to the total due to rounding.

SOURCE: MedPAC, 2020.

and lack supplemental coverage. These individuals are typically older Americans and often on fixed incomes (Jacobson et al., 2017). High patient out-of-pocket spending is associated with financial hardship, asset depletion and medical debt, distress and worry about household finances, and trade-offs in paying for routine daily needs, including food and housing (Ubel et al., 2013; Yabroff et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2019). Patients may delay or forgo needed medical care because of expected out-of-pocket costs (Briesacher et al., 2007; Laba et al., 2020; Reynolds et al., 2020). Again, while the number of patients affected by high out-of-pocket expenses for Part B drugs may be small, this population may be among the most vulnerable, and the financial burden on those patients to get the care they need may be overwhelming.

Although clinician-administered drugs currently account for a relatively small share of overall spending on prescription drugs, the spending is projected to increase in the coming years because of the rapidly increasing number of specialty medications coming to the market as single-dose

vials. The fundamental issues addressed by this report can inform an overarching approach to reducing certain inefficiencies in the system in which drugs are developed, administered, or paid for that lead to discarded drugs and the associated costs and could set a precedent that the rest of the health care sector could adopt.

QUESTION OF WASTE

According to its Statement of Task, the committee was charged to offer findings and recommendations on how to reduce waste in the biopharmaceutical supply chain, and given that the committee’s work was to focus specifically on the discarded portions of single-dose vials of weight-based drugs, it understood waste to be referring specifically to these discarded portions, which raised the question of how to understand the term. WHO uses the phrase waste pharmaceuticals to describe drugs that need to be disposed of for various reasons—because they are past their expiration date, for instance, or labeled in a way that makes them unrecognizable (WHO, 1999)—and the discarded portions of weight-based drugs could certainly be described as waste in this sense.

However, the term is used in a different way by researchers and other observers who are interested in the issue of efficiency in health care spending (Bentley et al., 2008; Berwick, 2019). In this context waste refers to any spending that does not produce as much value as it could have if it were directed differently. The existence of this sort of waste does not require a physical manifestation (e.g., discarded drugs), as the focus is on inefficiencies of any sort, but discarded drugs or other medical supplies could be an indication of waste. This waste can appear in a variety of forms: administrative waste (e.g., excess overhead costs), operational waste (e.g., duplication of services), and clinical waste (e.g., practices that do not improve health outcomes or are detrimental to the patient) (Bentley et al., 2008). In this conceptualization of waste, discarded portions of weight-based drugs might fit into the category of clinical waste—assuming that these indicated excessive spending.

On the surface, it can seem extremely wasteful that health care providers discard significant portions of a drug in single-dose vials that can cost thousands of dollars. And, indeed, it is that appearance of significant economic waste that has led observers to attempt to calculate the total value of drugs discarded in this way each year and to look for ways to minimize this waste. On the other hand, as the committee discovered in its deliberations and discussions with invited speakers to the committee’s public session, many economists who examine this system contend that the concept of waste is not the appropriate construct for assessing and addressing the issue of discarded drugs. Some even suggest that this

seemingly wasteful system of distributing weight-based drugs might actually be reasonably efficient. The reasons, as discussed in greater detail later in the report, can be found in the marginal costs of producing more drugs and in the factors that go into determining their pricing and paying for them.

This state of affairs presented the committee with a conundrum. But what if it is not appropriate to consider the discarded portions of single-dose vials to actually be fiscal waste? The committee’s solution was to approach this report as follows. In the next three chapters, the committee examines the issues surrounding discarded portions of weight-based drugs in single-dose vials from various perspectives—manufacturing, clinical, regulatory, and so on—and offers conclusions about some of the weaknesses of the system in which drugs are developed, administered, or paid for. In Chapter 5, the committee examines the economics of these weight-based drugs and, particularly, the issue of whether it is appropriate to consider discarded portions of single-use vials to be waste. Because the Statement of Task specifically charged the committee to look at financial implications, the committee focused on the economic value of discarded drugs. While a fuller discussion appears in Chapter 5, the committee ultimately decided that it is not appropriate to refer to the discarded portions as “waste” and that even if some inefficiency exists in the way these drugs are administered, the total economic value of discarded drug is nowhere near the amounts that have been suggested by simple calculations that multiply the nominal per-milliliter cost of the drugs by the total milliliters discarded each year. Nonetheless, there are important improvements that can be made to the system in which drugs are developed, administered, or paid for, and the committee does offer recommendations for such improvements in subsequent chapters.

STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT

Chapter 2 examines the factors in the U.S. biopharmaceutical supply chain that interact or compete to influence the amount of discarded drugs from weight-based dosing of drugs in single-dose vials and the patient safety and quality-of-care issues related to weight-based drugs. Chapter 3 gives an overview of the amounts of drugs being discarded. Chapter 4 discusses the actions of various stakeholders, including Congress, nongovernmental and professional organizations, and hospitals and clinicians, to reduced discarded drugs resulting from the use of weight-based drugs in single-use vials. As noted earlier, Chapter 5 focuses on the economic issues related to single-dose, weight-based drugs and explains why waste is not the right construct to analyze the issue of discarded drugs. Chapter 6 contains the committee’s goals and reiterates its recommendations.

The report’s appendixes present supplemental information on conducting the study. Appendix A contains the glossary of key terms used in the report; Box 1-2 provides some of these. Appendix B contains supplemental information for the committee’s commissioned analyses. Appendix C lists experts who spoke at the committee’s public sessions and organizations that submitted comments on the study. Appendix D provides committee and staff biographies. Finally, Appendix E provides information on the disclosure of unavoidable conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

ASPE (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation). 2020. Report to Congress: Prescription drug pricing. May 2020. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/aspefiles/263451/2020-drug-pricing-report-congress-final.pdf (accessed October 27, 2020).

Bentley, T. G., R. M. Effros, K. Palar, and E. B. Keeler. 2008. Waste in the US health care system: A conceptual framework. The Milbank Quarterly 86(4):629–659.

Berwick, D. M. 2019. Elusive waste: The Fermi paradox in US health care. JAMA 322(15):1458–1459.

Briesacher, B. A., J. H. Gurwitz, and S. B. Soumerai. 2007. Patients at-risk for cost-related medication nonadherence: A review of the literature. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22(6):864–871.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2020. Medicare Part B: Drug average sales price. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Part-B-Drugs/McrPartBDrugAvgSalesPrice (accessed August 4, 2020).

Cubanski, J., T. Neuman, S. True, and M. Freed. 2019. What’s the latest on Medicare drug price negotiations? http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Whats-the-Latest-on-Medicare-Drug-Price-Negotiations (accessed August 31, 2020).

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2018. Selection of the appropriate package type terms and recommendations for labeling injectable medical products packaged in multiple-dose, single-dose, and single-patient-use containers for human use guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/117883/download (accessed August 8, 2020).

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2015. Medicare Part B: Expenditures for new drugs concentrated among a few drugs, and most were costly for beneficiaries. GAO-16-12 October. Washington, DC: GAO.

IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. 2019. Medicine use and spending in the U.S.: A review of 2018 and outlook to 2023. https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institutereports/medicine-use-and-spending-in-the-us---a-review-of-2018-outlook-to-2023.pdf?_=1596563978024 (accessed August 8, 2020).

Jacobson, G., S. Griffin, T. Neuman, and K. Smith. 2017. Income and assets of Medicare beneficiaries, 2016–2035. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/income-and-assets-of-medicare-beneficiaries-2016-2035 (accessed December 16, 2020).

Kanavos, P., A. Ferrario, S. Vandoros, and G. F. Anderson. 2013. Higher U.S. branded drug prices and spending compared to other countries may stem partly from quick uptake of new drugs. Health Affairs 32(4):753–761.

Kesselheim, A. S., J. Avorn, and A. Sarpatwari. 2016. The high cost of prescription drugs in the United States: Origins and prospects for reform. JAMA 316(8):858–871.

Laba, T. L., L. Cheng, A. Kolhatkar, and M. R. Law. 2020. Cost-related nonadherence to medicines in people with multiple chronic conditions. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 16(3):415–421.

Lotvin, A. M., W. H. Shrank, S. C. Singh, B. P. Falit, and T. A. Brennan. 2014. Specialty medications: Traditional and novel tools can address rising spending on these costly drugs. Health Affairs 33(10):1736–1744.

MedPAC (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission). 2020. A data book: Health care spending and the Medicare program. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/july2020_databook_entirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0 (accessed August 4, 2020).

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2018. Making medicines affordable: A national imperative. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Papanicolas, I., L. R. Woskie, and A. K. Jha. 2018. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA 319(10):1024–1039.

Reynolds, E. L., J. F. Burke, M. Banerjee, K. A. Kerber, L. E. Skolarus, B. Magliocco, G. J. Esper, and B. C. Callaghan, 2020. Association of out-of-pocket costs on adherence to common neurologic medications. Neurology 94(13):e1415–e1426.

Sarnak, D. O., D. Squires, G. Kuzmak, and S. Bishop. 2017. Paying for prescription drugs around the world: Why is the U.S. an outlier? Commonwealth Fund Issue Brief 1–14.

Ubel, P. A., A. P. Abernethy, and S. Y. Zafar. 2013. Full disclosure—out-of-pocket costs as side effects. New England Journal of Medicine 369(16):1484–1486.

Werble, C. 2017. Medicare Part B. Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20171008.000171/full (accessed November 20, 2020).

WHO (World Health Organization). 1999. Guidelines for safe disposal of unwanted pharmaceuticals in and after emergencies. https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/medicalwaste/unwantpharm.pdf (accessed November 20, 2020).

WHO. 2020. The Global Health Observatory. Life expectancy at birth (years). https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/life-expectancy-at-birth-(years) (accessed November 20, 2020).

Yabroff, K. R., J. Zhao, Z. Zheng, A. Rai, and X. Han. 2018. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: What do we know? What do we need to know? Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers 27(12):1389–1397.

Zheng, Z., A. Jemal, X. Han, G. P. Guy, Jr., C. Li, A. J. Davidoff, M. P. Banegas, D. U. Ekwueme, and K. R. Yabroff. 2019. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer 125(10):1737–1747.