4

MAKING DECISIONS ABOUT IMPLEMENTATION

Given the broad array of care interventions, services, and supports that have been developed for persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers and the varying degree to which these interventions are supported by evidence of efficacy, stakeholders in dementia care face challenging decisions regarding whether and how to implement a given intervention. How these decisions are made, including the type of evidence and other information taken into account, will vary for different stakeholders, such as persons living with dementia, care partners and caregivers, health care and long-term services and supports (LTSS) providers, care systems, payers, and policy makers. Innovative, evidence-based models of dementia care often are not widely deployed or put to broad practical use in care settings (Gitlin et al., 2015), and those interventions that are implemented often lack a strong evidence base supporting their use (Lourida et al., 2017). Many providers and consumers, moreover, have little information about the interventions available to them.

Different processes are used to develop the evidence base for nonpharmacological and pharmaceutical interventions for dementia care. Once efficacy has been established for a nonpharmacological intervention, implementation testing in real-world care settings is required to define the benefit of the intervention in actual care settings in preparation for its widespread dissemination. Implementation testing builds the evidence base on just what benefits the intervention provides under which conditions. It also helps identify adaptations that may be needed for the intervention’s successful application within different systems of care, organizational structures, workflows, payment models, and cultures, and can assist decision makers in

anticipating the resources required to implement and sustain the intervention in their own care systems (Sohn et al., 2020). The sustainability of an intervention being implemented in a facility, organization, or system is an important consideration, as the dynamic nature of dementia care practice requires the allocation of limited resources to proven interventions and an understanding of the integration of interventions into particular systems and organizations (Walugembe et al., 2019). Studying approaches for dissemination is also an important component of implementation testing.

In considering which dementia care interventions, services, and supports are ready for dissemination and implementation on a broad scale, the committee sought to understand the implementation science behind the translation of evidence-based interventions into routine practice in care settings, as well as in the community (i.e., by persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers). Reviews of the salient literature reveal few published reports on the implementation of evidence-based dementia care interventions (Gitlin et al., 2015; Lourida et al., 2017), despite evidence that both individual and contextual factors can alter the effectiveness of an intervention in achieving desired outcomes (Unützer et al., 2020). Accordingly, the committee’s deliberations on implementation issues were further informed by discussions with experts in implementation science and with representatives of care systems, payers, and advocacy organizations and associations that took place during the public workshop held for this study (see Appendix B).

APPLYING IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE1

Implementation science is the study of methods and strategies for promoting the translation of research findings and evidence-based practices and interventions into routine care and policy (Eccles and Mittman, 2006; University of Washington, 2020). Research in implementation science strives to understand what facilitates adoption of an intervention by end users, as well as what creates barriers to its uptake. Applying implementation science to the growing body of interventions for dementia care reveals that stakeholders consider many types of information in addition to effectiveness when making decisions about whether and how to implement these interventions in the real world. Care and service providers, as well as payers, also may consider such metrics as costs, return on investment, value, and quality indicators (Lees Haggerty et al., 2020; Teisberg et al., 2020).

___________________

1 Some of the content of this section was drawn from the committee’s discussion with two experts in implementation science research—Laura Gitlin of Drexel University and Melissa Simon of Northwestern University—which took place during the public workshop held on April 15, 2020. See Appendix B for the public workshop agenda.

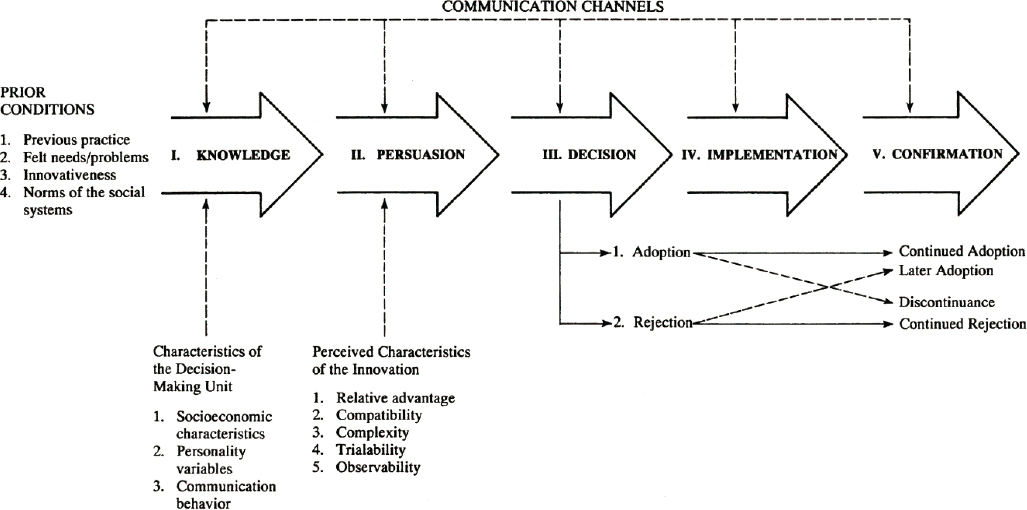

Ultimately, it is the organization implementing or individuals receiving an intervention—not the intervention’s developer—that determine its value or “relative advantage” (Rogers, 2003) (see Figure 4-1). That value derives from the benefits or outcomes that end users perceive they are receiving from use of the intervention. An intervention might be chosen, for example, because, compared with other interventions, it saves time, is convenient or hassle-free, offers greater patient satisfaction, or has a good reputation or image (Callahan et al., 2018). It is therefore important to identify those stakeholders and end users (e.g., persons living with dementia, care partners and caregivers, health care and LTSS providers, care systems, payers, policy makers) who hold the decision-making power and to understand what qualities they value in an intervention (Callahan et al., 2018; Gitlin et al., 2015).

Frameworks for Implementing and Evaluating Interventions in Complex Systems

The paucity of published reports describing the translation of research on dementia care interventions into practice hinders the advancement of translation efforts (Gitlin et al., 2015). Reviews of dementia care intervention studies that report on implementation efforts have found that a theory or framework is often used to facilitate practice change and audit translation success. This section describes a few of the many theoretical frameworks available for evaluating translation efforts and understanding the facilitators of and barriers to implementation (Gitlin et al., 2015).

One instrument commonly used to evaluate translation in implementation science and health services research is the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework, designed to facilitate the translation of scientific evidence into public health impact and policy by increasing transparency in research and reevaluating the balance between internal validity and external validity (generalizability) (Glasgow et al., 2019). RE-AIM has been used in several studies evaluating dementia interventions (Gitlin et al., 2015; Lourida et al., 2017).

Another framework used in the field of implementation science is Normalization Process Theory (NPT), which lays out specific factors researchers might consider when incorporating and evaluating complex interventions in practice, posing questions related to coherence, cognitive participation or engagement, collective action, and reflexive monitoring (Murray et al., 2010). This framework, which considers the interactions of individual- and organizational-level factors, helps identify factors within these four components that enable or inhibit the normalization of complex interventions or their full integration into routine practice. NPT argues for considering how interventions can be sustained in practice from the start of their development.

SOURCE: DIFFUSION OF INNOVATIONS, 5E by Everett M. Rogers. Copyright © 1995, 2003 by Everett M. Rogers. Copyright © 1962, 1971, 1983 by Free Press. Reprinted with the permission of The Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

Other frameworks take into account the complexities of health care delivery, potential barriers to implementation, and stakeholder perspectives on value. One example is the Agile Implementation Framework, developed by Indiana University. This framework reprioritizes eight implementation steps, so that the process starts with proactive assessment of the demand from end users rather than with the innovator’s perspective and then directs the development of a scalable, sustainable solution accordingly. The framework facilitates tailoring of an intervention to the local environment; timely feedback and process modification; monitoring and assessment of impact, unintended consequences, and emergent behaviors that promote or deter uptake; and regularly updated documentation of the process to facilitate the spread and scaling of the intervention (Boustani et al., 2018; Callahan et al., 2018). This framework has been demonstrated in the implementation of a sustained collaborative dementia care model (Boustani et al., 2018).

Curran and colleagues (2012) propose a hybrid approach to study design that combines components of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to allow for more rapid translational gains, effective implementation strategies, and useful information for decision makers. They describe three hybrid models: (1) test a clinical intervention while collecting information on its delivery and implementation, (2) simultaneously test both a clinical intervention and an implementation intervention or strategy, and (3) test an implementation intervention or strategy while collecting information on the clinical intervention and its outcomes (Curran et al., 2012).

Proctor and colleagues (2011) developed a taxonomy of eight implementation outcomes—acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, penetration, and sustainability. Researchers can use this taxonomy to conceptualize and evaluate the implementation of an intervention (Proctor et al., 2011).

Carroll and colleagues (2007) provide a conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. They describe three areas of evaluation: (1) adherence (content, coverage, frequency, and duration); (2) moderators that might influence fidelity (intervention complexity, facilitation strategies, quality of delivery, and participant responsiveness); and (3) identification of essential components (i.e., components of the intervention that have the most impact) (Carroll et al., 2007).

Finally, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), developed by Damschroder and colleagues (2009), synthesizes existing theoretical frameworks to produce a list of constructs that guide researchers to examine what works, where, and why across multiple contexts. The 37 CFIR constructs fall within five major domains: intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of the individuals involved, and the implementation process (Damschroder et al., 2009).

Barriers to Implementation

Many of the barriers to the uptake of new models of dementia care, services, and supports that have been described are organizational, often revolving around workforce issues and workload/time constraints (Lourida et al., 2017). Implementing a new model might require redesigning practice, redefining professional roles, providing training for existing staff, or hiring new personnel. The ability to integrate a new care model into practice and to train or hire the necessary workforce is also impacted by the model’s complexity. In some cases, a shortage of qualified personnel (e.g., limited availability of behavioral health professionals with expertise in dementia) presents a barrier. Higher rates of staff turnover have also been described as a barrier to implementation, decreasing fidelity to an intervention’s defined practice model (Woltmann et al., 2008). Costs and financial sustainability can be additional considerations in deciding to implement a new model of care. There may be start-up costs (e.g., the need to acquire technology or adapt infrastructure), or coverage by third-party payers may be insufficient (Callahan et al., 2018; Lees Haggerty et al., 2020). Moreover, the pace of uptake of new models of care is impacted by the extent to which implementation requires changes in organizational culture or coordination across departments (Bradley et al., 2004; Proctor et al., 2011).

Challenges persist for those implementing evidence-based interventions that could improve the quality of life for both persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers. Many persons living with dementia, care partners and caregivers, and providers are not aware of or able to access these interventions. Another challenge is the clinical relevance of the evidence. For example, interventions being studied for dementia care are often not classified according to disease stage or etiology, making it difficult for providers to identify interventions that might achieve a desired outcome for a given patient at a particular stage of disease (Gitlin et al., 2015). Information on the use of interventions in demographic subgroups is also limited.

Still another challenge is that studies often do not discuss the clinical significance of the findings they are reporting—that is, whether the effect being demonstrated really matters to stakeholders. There is often little information available about the cost of implementing an intervention or about its cost-effectiveness, potential cost savings, or what burden of cost families are willing to bear to realize desired outcomes. Furthermore, not all studies consider outcomes that might be considered meaningful by caregivers, such as outcomes that improve their quality of life and reduce the personal, physical, and financial burdens of caring for a person living with dementia, or address other unmet care needs (Gitlin et al., 2015).

Underlying many of the barriers to implementation are core differences in priorities. The research process prioritizes the discovery of new

and, ideally, generalizable knowledge, and is not necessarily focused on pragmatic application in real-world settings. Furthermore, few scientists in the field of aging research have expertise in implementation science. A challenge in the field of dementia care research is bridging researchers’ expectation that the implementation and dissemination of their interventions will be taken up by other parties, which is often not the case (Callahan et al., 2018), and the demand for effective interventions. Policy makers, practitioners, persons living with dementia, and care partners and caregivers prioritize knowledge about practical ways to apply interventions in their context. Although the purpose of developing dementia care interventions is to meet the needs of persons living with dementia, care partners, and caregivers, they are rarely consulted or engaged in the development or implementation process. This represents a lost opportunity for researchers to allow persons living with dementia, care partners, and caregivers to determine the outcomes that matter to them and should be measured. This lack of up-front consideration of dissemination and implementation during intervention design is a key barrier that some intervention development models are working to address. The National Institute on Aging’s (NIA’s) IMbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease–related dementias Clinical Trials (IMPACT) Collaboratory has begun to address this barrier by promoting embedded pragmatic clinical trials to evaluate dementia care interventions in real-world health care systems. Nonetheless, much work remains to be done to bridge the gap in priorities between health services researchers and the individuals who want access to effective interventions.

Facilitators of Implementation

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development is a six-stage process designed to facilitate the production of “highly potent and maximally implementable behavioral interventions that improve health and well-being” (NIA, 2018). The six stages of the model are

- Stage 0: basic science research that occurs prior to intervention development;

- Stage I: activities related to the creation and preliminary testing of an intervention;

- Stage II: pure efficacy research that involves experimental testing of interventions in research settings with research-based providers;

- Stage III: real-world efficacy research that involves experimental testing in community settings with community-based providers, while still maintaining control to establish internal validity;

- Stage IV: effectiveness research in community settings with community-based providers that aims to maximize external validity; and

- Stage V: implementation and dissemination research that examines strategies of adopting an intervention in community settings.

According to the model, “intervention development is not complete until an intervention reaches its maximum level of potency and is implementable with a maximum number of individuals in the population for which it was developed,” and the model specifically calls for implementation to be considered in the early stages of development (NIA, 2018).

Conditions that have been identified as being supportive of the uptake and implementation of new care models by organizations include alignment with health system priorities, buy-in and managerial support by organizational leadership, clinical leaders who champion the model, workforce education and training, sustainable funding/financial resources, and a dedicated infrastructure for translation activities (Bradley et al., 2004; Callahan et al., 2018; Lourida et al., 2017). The NIH Stage Model emphasizes that designing training and supervisory materials is an essential part of intervention development, helping to ensure that an intervention is administered with fidelity by providers or caregivers (NIA, 2018). There are also external factors, such as regulatory compliance, reimbursement incentives, and market pressures, that can compel implementation (Bradley et al., 2004).

The evolution of the health care payment system from a fee-for-service to a value-based model has been described as a positive development for the implementation of evidence-based dementia care. The Population Health Value framework was designed to create value and reduce costs by developing targeted pathways to care for patient populations with high expenses due to chronic conditions, including individuals living with dementia (Gupta et al., 2019). Yet, the current reimbursement system for dementia care has numerous gaps and does not cover the delivery of many of the evidence-based care models that a care plan might include. Notably, Medicare offers very limited reimbursement for LTSS (Colello, 2018). New payment models specific to dementia care have therefore been proposed. In 2017, for example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) added a new reimbursement benefit covering the development of a written care plan for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias and cognitive disorders (Borson et al., 2017). This benefit provides for assessment and care planning, but its scope is limited, excluding ongoing care management services. In fact, services are covered only if they are provided by selected medical professionals, and not if they are provided by community-based organizations or in the context of collaborative dementia care models. One proposal to close this gap is an alternative payment model covering care management services for community-dwelling persons living with dementia.

This model would provide a per-beneficiary, per-month payment to beneficiaries, and would also provide services, education, and support to their unpaid caregivers (Boustani et al., 2019).

Finally, as noted earlier, involving all relevant stakeholders early on in the development of dementia care interventions has been discussed as an approach to reducing the barriers to dissemination and implementation (Callahan et al., 2018; Gitlin et al., 2015). By partnering with stakeholders up front, researchers can better understand the context of use of an intervention and the potential end users’ needs and decision-making processes (i.e., the demand).

Deciding Whether and How to Implement an Intervention

The care delivery system has been described as a complex adaptive system in which networks of stakeholders coevolve within a changing environment. Implementing new interventions and evaluating their performance in both complex health care and public health systems is challenging, and traditional randomized controlled trials or systematic reviews are often not well suited to the task (Boustani et al., 2010; Rutter et al., 2017). There is no consensus around what constitutes sufficient evidence for deciding which interventions should advance to the implementation testing stage and dissemination. Furthermore, different studies use different methodologies to assess the evidence, and methods for evaluating the extent to which a methodology or metric is relevant to dementia care do not currently exist.

Tools have been developed to aid clinicians, policy makers, and other stakeholders in rating the quality of the available evidence as they make and implement recommendations and decisions that will guide care. One widely used decision tool is the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) group’s Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework which can be applied to making and using clinical recommendations, coverage decisions, and health system and public health recommendations and decisions (Alonso-Coello et al., 2016; Moberg et al., 2018). This framework takes systematic reviewers and decision makers through a structured and transparent process of formulating a question based on a defined problem, making an evidence-based assessment, and drawing conclusions based on the best available research evidence. Factors taken into account in the assessment go beyond effectiveness and can include the priority of the problem, how substantial the benefits and harms of the intervention or option in question are, the certainty of the evidence, the value of the outcomes to stakeholders, how the intervention or option compares with others, resource requirements, cost-effectiveness versus comparable options, the impact on health equity, the acceptability of the intervention or option to stakeholders, and the feasibility of implementa-

tion. Conclusions drawn from the assessment might also include guidance for implementation and recommendations for monitoring and evaluation (Moberg et al., 2018). It is essential for care decisions to be based on the available evidence, and frameworks such as GRADE EtD not only support the experts who make those decisions but also help those affected by the decision understand why and how a decision was made (i.e., the strength of the evidence on which it was based) as they work to implement it in their specific circumstances. The GRADE EtD framework is discussed in greater detail and applied to specific interventions in Chapter 5.

There is also an evolving approach to systematic review in support of decision making on health interventions that incorporates a complex interventions and systems-oriented perspective (Petticrew et al., 2019). This perspective may be particularly useful when an intervention consists of multiple components, when the casual pathway between intervention and outcome is not linear, or when the effects of the intervention are context-dependent.

Monitoring and Evaluation, Quality Improvement, and Information Sharing

Given that much of the learning and knowledge generation for complex systems occurs in local and individual settings, monitoring and evaluation are crucial components of intervention implementation that need to be considered from the outset of intervention development (NAE, 2011). Monitoring can be considered an ongoing activity carried out throughout the implementation process to track the performance of an intervention by measuring inputs, such as financial and staff resources, and outputs, such as services provided and the intervention’s coverage (WHO, 2004). Monitoring is often performed by the staff who are implementing the intervention. Evaluation is an episodic assessment that can be performed by project staff, sponsors, or an external third party, aimed at understanding the intervention’s effect in producing specified outcomes (WHO, 2004). The outcomes targeted by these evaluations can be categorized broadly as (1) process outcomes (e.g., the intervention’s content, coverage, or quality); (2) short-term outcomes (e.g., behavior, depression, cost-effectiveness); or (3) long-term impact (e.g., quality of life). It is important that monitoring and evaluation encompass both anticipated benefits of the targeted outcome and any unintended consequences that worsen the care of a condition or a system outside of the targeted area.

A preimplementation assessment of the capacities and needs of the individuals and organizations involved in the intervention can help identify barriers to and facilitators of implementation, as well as areas that may require closer monitoring during implementation (Damschroder et

al., 2009). Similarly, the monitoring of progress during implementation and the collection of real-time data are important to detect unanticipated barriers to or facilitators of implementation, as well as to identify and address any potential problems before they can compromise the intervention’s viability. The data collected may include both quantitative and qualitative information gathered through reflection, debriefs, and feedback among intervention staff regarding the progress and quality of implementation, discussions that can also promote shared learning and quality improvement as the implementation proceeds. In addition to ongoing monitoring, evaluations of clinical outcomes and formative evaluations are critical to understand the processes by which the intervention is implemented, the financial resources required, how context modifies effectiveness, and how the intervention can be optimized for other contexts (Curran et al., 2012; Damschroder et al., 2009; Proctor et al., 2011). It is essential for formative evaluations to be designed to assess the perceptions of stakeholders delivering and receiving the intervention, such as persons living with dementia, care partners and caregivers, providers, and administrators (Curran et al., 2012; Damschroder et al., 2009). In some instances, evaluations may be informative in indicating that there is little chance of successful implementation, and resources could better be used elsewhere (Murray et al., 2010).

To support monitoring, evaluation, and quality improvement, data will ideally be gathered from clinical research as well as clinical encounters and other services and supports settings in the community. These data will then be stored and shared among various settings involved in the delivery of care, services, and supports to persons living with dementia, care partners, and caregivers (IOM, 2013). To improve the data collection, implementers can leverage health information technology—for example, using information that is already collected in electronic health records. Patient-generated health data, provided directly by intervention participants or their designees, are another rich source of information about patients’ health-related experiences and concerns in daily life (IOM, 2015).

To support comprehensive understanding of an intervention’s implementation, it is important to collect performance and quality data across the spectrum of care settings, including medical care and LTSS (NASEM, 2016). The National Strategy for Quality Improvement, developed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), advocates for transparent, accountable, person-centered, and higher-quality care through partnerships between provider networks and across varying settings. According to a previous report of the National Academies, however, these attributes often are not present in quality measurement practices. Within HHS, CMS, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are some of the federal agen-

cies working specifically on health data quality improvement efforts (IOM, 2015). The National Quality Forum has also recommended priorities for addressing gaps in the quality assessment of home- and community-based services, including the integration of quality data with encounter, authorization, and administrative data to facilitate the use of real-time data collection to support quality improvement (NQF, 2016). Importantly, long-term care facilities and community-based providers, which operate outside of traditional health systems that routinely collect clinical and personal data, need a data infrastructure capable of capturing and sharing data that can be used to improve the quality of care (IOM, 2015). An Electronic Long-Term Services and Supports Plan that was part of CMS’s Testing Experience and Functional Tools demonstration showed promise for harmonization of data and coordination across care settings (The Lewin Group, 2018).

UNDERSTANDING DEMAND: STAKEHOLDER PERSPECTIVES ON DECISION MAKING2

During its public information-gathering workshop, the committee heard on-the-ground perspectives from stakeholders in dementia care, including representatives of advocacy organizations and associations and care systems and payers.

Advocacy Organizations and Associations

Representatives of advocacy organizations and associations expressed to the committee their view that persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers need interventions and support now. They stated that decisions regarding which interventions to try, for which individuals, in which situations, with the available resources are being made using the best evidence currently available. Ideally, the selection of interventions would be based on rigorous evidence of effectiveness, but lacking that evidence, decision makers take a range of individual, interventional, and contextual criteria and characteristics into consideration.

Lynn Feinberg of AARP shared her perspective that the main barriers to scaling up evidence-based dementia interventions are the lack of technical assistance and guidelines for providers in determining which caregivers could benefit from which interventions; the lack of up-front consideration of dissemination and implementation during intervention design; and the

___________________

2 The content of this section was drawn from the committee’s discussions with representatives of advocacy organizations and associations and care systems and payers that took place during the public workshop held on April 15, 2020. See Appendix B for the public workshop agenda.

lack of sufficient funding and payment mechanisms covering evidence-based caregiver support services in practice settings. Despite the persistent gaps in the implementation evidence base for dementia care interventions, persons living with dementia and care partners and caregivers must move forward and make evidence-informed decisions regarding the available interventions. The view Feinberg expressed to the committee is that the need for more rigorous research should not delay the scale-up and promotion of evidence-informed practices and caregiver support services and programs for families that need help.

Kathleen Kelly of Family Caregiver Alliance stated that care situations are dynamic, and the Alliance looks to identify interventions and supports that meet a dementia caregiver’s needs wherever they fall along the spectrum of care. The Alliance conducts a uniform assessment to develop a care plan tailored to the needs of the family, and moves forward using the best evidence-based interventions available at the time. Unfortunately, where an intervention fits best along the spectrum of care is not always clear, and efforts are further hampered by the lack of a common language for assessment of caregiver needs. Practical issues of intervention implementation also need to be considered, such as staffing needs (e.g., whether the intervention is delivered in a group or one-to-one); training needs (and whether a training or operations manual or technical assistance is available); and resource needs (e.g., whether app, online, or telehealth resources are available and whether the family has access to the Internet).

Douglas Pace of the Alzheimer’s Association highlighted the finding from the AHRQ systematic review that insufficient evidence of an intervention’s effectiveness does not equate to its being ineffective. He emphasized the importance of ensuring that interventions remain available to those who find them helpful while the evidence base to support more widespread dissemination is being assembled. He pointed out that many care interventions are ready for dissemination, and for others, existing data can be leveraged and shared collaboratively to grow the evidence base. In considering which interventions to try, it is important to consider the desires of persons living with dementia and care partners and caregivers and the accessibility of the interventions to them. For example, “short-term low-touch interventions” are needed in conjunction with or as an alternative to more comprehensive programs and services.

In reflecting on the five domains in which the AHRQ review assessed the strength of the evidence base for interventions (study limitations, consistency, directness, precision, reporting bias), Kelly, Pace, and Feinberg each indicated that criteria related to consistency and directness (a direct link between intervention and outcome) were the most important contributors to their organization’s decision-making process. The recommendations of the Service Providers Stakeholder Group at the 2020 Research Summit

on Dementia Care were also noted,3 and Pace emphasized the underlying recommendation themes of person-centered care and diversity, equity, and inclusion in the development, evaluation, dissemination, and implementation of dementia care interventions.

Care Systems and Payers

Representatives of care systems and payers expressed opinions similar to those of other stakeholders regarding elements of decision making.4 Payers are particularly interested in whether interventions are consistently achieving the intended outcomes in the intended population, as integrated in the care system and implemented by the end user.

Patrick Courneya of HealthPartners suggested that implementation and dissemination decisions sit at the intersection of what is determined to be of value based on evidence of efficacy and what is meaningful to individuals and their personal experiences and circumstances. The principle of “first do no harm” must be balanced against the strength of the evidence for whether an intervention does or does not work. According to Courneya, there is an opportunity to create infrastructure for the collection of pragmatic, real-world information about the effectiveness of organizations and service providers in delivering covered services consistently, and about whether the intervention’s delivery is having the intended impact in the community or there are any unanticipated effects. From a decision-making perspective, it is important to understand who specifically derives benefits from the intervention (e.g., persons living with dementia, care partners and caregivers, employers, society, other stakeholders). Payers take into account how widely available the intervention is, the associated costs, and how it compares with other approaches. Other considerations might include how practicable and logistically feasible an intervention is, whether it can be deployed with fidelity, and whether its performance can be reliably monitored.

David Gifford of the American Health Care Association said he often hears from providers that interventions supported by a solid evidence base are not effective in their hands. He attributed this disconnect not to issues with the evidence but to problems with workflow, integration, and implementation. To be successful, tools and strategies must be integrated within the health care delivery system, and this aspect of an intervention

___________________

3 More information about the summit and recommendations developed by the Service Providers Stakeholder Group is available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/research-summit-dementia-care-2020-stakeholder-groups (accessed August 18, 2020).

4 More information about the summit and recommendations developed by the Payer Stakeholder Group is available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/research-summit-dementia-care-2020-stakeholder-groups (accessed August 18, 2020).

is often overlooked. Another consideration for implementation is the type of intervention. Pharmaceutical products that target the pathophysiology of dementia are not necessarily the type of intervention that will provide the desired outcome for an individual grappling with a lost function or cognitive domain. With regard to decision making, providers and policy makers bypass studies that conclude only that more study is needed, and they gravitate toward those studies that do draw a conclusion, even if the evidence is poor. According to Gifford, the evidence base used by decision makers would benefit from researchers drawing conclusions when possible, with caveats if needed.

Lewis Sandy of UnitedHealth Group pointed out that many persons living with dementia are Medicare beneficiaries, as are many care partners and caregivers. Thus, when considering who will be implementing dementia care interventions, it is important to understand how Medicare operates. Whereas what can be covered by traditional Medicare is governed by statute and regulation, Medicare Advantage plans have more flexibility to offer additional benefits, and many provide in-home support, telemonitoring, and support for caregivers. There are special needs plans for those with chronic health conditions; however, very few of these plans are targeted toward dementia. From a payer perspective, evidence that might not meet the evidentiary standards for publication or is not statistically significant can still be of interest to inform their decisions. Payers are particularly interested in interventions that are ready to scale and have been demonstrated to be robust across a range of implementation conditions (e.g., populations, geographies, care settings).

Shari Ling of CMS said that a challenge for CMS is making decisions based on an evidence base that varies widely in the outcomes reported. The Medicare population lives with multiple comorbidities, and it would be helpful to have a core set of meaningful outcome measures to help align the science with practice and policy. It would also be helpful to define universal processes and indices of outcomes that are meaningful for caregivers and could be incorporated into clinical trials. When considering readiness for implementation, it is important to identify who will implement an intervention (e.g., persons living with dementia, care partners/caregivers, clinicians, practices, systems) and understand how they will use it (including how it will fit into the workflow). Medicare is defined by statute, and CMS must adhere to program and policy implementation levers when deploying interventions. When deciding about coverage, for example, CMS must look for evidence that an intervention meaningfully improves outcomes in the intended population. In this case, it is important for the target population to be clearly defined. Quality measurement requires having a clearly defined numerator (the outcome to be achieved) and denominator (the population in which it is to be achieved). In the work of the CMS Innovation Center, it

must be demonstrated that care models and payment models are achieving improved quality.

Workshop participants also discussed the level of evidence needed and other considerations in deciding whether to launch an embedded pragmatic clinical trial, noting that buy-in from providers and organizational leadership is essential for trial success. Considerations include the burden the trial will impose on providers who will have to implement the intervention for the trial (e.g., whether the intervention will integrate into the existing workflow); the potential scalability of the intervention; and the adaptability of the trial design, as adaptable designs are more likely to yield useful results. Cost considerations for both care systems and payers include not only the costs of the intervention itself but also the costs entailed at every step in the implementation process, from identifying and then engaging the target population for the intervention, to delivering the intervention with fidelity, to carrying out measurement and evaluation. Cost savings that an intervention may offer to payers or providers are also a consideration (and are a mandated consideration for programs of the CMS Innovation Center).

CONCLUSIONS

Given the complexity of dementia care interventions, it is challenging to evaluate how and under what circumstances they can be implemented to move the evidence base beyond efficacy and even pragmatic trials toward readiness for implementation and dissemination. The collection and publication of translational evidence relevant to implementation remain insufficient. Multiple frameworks and tools are available to help fill this evidence gap and enable evaluation and better understanding of the barriers to, facilitators of, and readiness for intervention implementation. More work to incorporate implementation science into the design, monitoring, and evaluation of interventions will be important to the continuing advancement of improvements in dementia care.

CONCLUSION: Interventions that demonstrate efficacy in a clinical trial or other controlled research setting need to be adapted to local settings, tailored to the targeted populations, and monitored and evaluated to assess their effectiveness when translated to an uncontrolled clinical or community setting and to guide adjustments to the implementation process. Some adaptations of and changes to the implementation context and conditions will undermine effectiveness, and some interventions with efficacy may not work in real-world settings.

CONCLUSION: To inform decisions about whether and under what circumstances to implement and fund an intervention, stakeholders—such as persons living with dementia, care partners and caregivers, health care and long-term services and supports providers, care systems, payers, and policy makers—consider evidence on effectiveness; stakeholder values; and the contexts in which an intervention may be implemented, such as individual characteristics of participants (e.g., stage of dementia, race/ethnicity), organizational structure, workforce, and payment models. Different stakeholders may use different criteria to inform their decisions on the implementation of dementia care interventions.

REFERENCES

Alonso-Coello, P., H. J. Schünemann, J. Moberg, R. Brignardello-Petersen, E. A. Akl, M. Davoli, S. Treweek, R. A. Mustafa, G. Rada, S. Rosenbaum, A. Morelli, G. H. Guyatt, and A. D. Oxman. 2016. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: A systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ 353:i2016.

Borson, S., J. Chodosh, C. Cordell, B. Kallmyer, M. Boustani, A. Chodos, J. K. Dave, L. Gwyther, S. Reed, D. B. Reuben, S. Stabile, M. Willis-Parker, and W. Thies. 2017. Innovation in care for individuals with cognitive impairment: Can reimbursement policy spread best practices? Alzheimer’s & Dementia 13(10):1168–1173.

Boustani, M. A., S. Munger, R. Gulati, M. Vogel, R. A. Beck, and C. M. Callahan. 2010. Selecting a change and evaluating its impact on the performance of a complex adaptive health care delivery system. Clinical Interventions in Aging 5:141–148.

Boustani, M., C. A. Alder, and C. A. Solid. 2018. Agile implementation: A blueprint for implementing evidence-based healthcare solutions. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 66(7):1372–1376.

Boustani, M., C. A. Alder, C. A. Solid, and D. Reuben. 2019. An alternative payment model to support widespread use of collaborative dementia care models. Health Affairs 38(1):54–59.

Bradley, E. H., T. R. Webster, D. Baker, M. Schlesinger, S. K. Inouye, M. C. Barth, K. L. Lapane, D. Lipson, R. Stone, and M. J. Koren. 2004. Translating research into practice: Speeding the adoption of innovative health care programs. Issue Brief (Commonwealth Fund) (724):1–12.

Callahan, C. M., D. R. Bateman, S. Wang, and M. A. Boustani. 2018. State of science: Bridging the science-practice gap in aging, dementia and mental health. Journal of the American Geriatriatric Society 66(Suppl 1):S28–S35.

Carroll, C., M. Patterson, S. Wood, A. Booth, J. Rick, and S. Balain. 2007. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Science 2(1):40.

Colello, K. J. 2018. Who pays for long-term services and supports? Congressional Research Service, August 22. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF10343.pdf (accessed January 21, 2021).

Curran, G. M., M. Bauer, B. Mittman, J. M. Pyne, and C. Stetler. 2012. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care 50(3):217–226.

Damschroder, L. J., D. C. Aron, R. E. Keith, S. R. Kirsh, J. A. Alexander, and J. C. Lowery. 2009. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science 4(1):50.

Eccles, M. P., and B. S. Mittman. 2006. Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science 1(1):1.

Gitlin, L. N., K. Marx, I. H. Stanley, and N. Hodgson. 2015. Translating evidence-based dementia caregiving interventions into practice: State-of-the-science and next steps. Gerontologist 55(2):210–226.

Glasgow, R. E., S. M. Harden, B. Gaglio, B. Rabin, M. L. Smith, G. C. Porter, M. G. Ory, and P. A. Estabrooks. 2019. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: Adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Frontiers in Public Health 7(64).

Gupta, R., L. Roh, C. Lee, D. Reuben, A. Naeim, J. Wilson, and S. A. Skootsky. 2019. The population health value framework: Creating value by reducing costs of care for patient subpopulations with chronic conditions. Academic Medicine 94(9):1337–1342.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2013. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2015. Vital signs: Core metrics for health and health care progress. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Lees Haggerty, K., G. Epstein-Lubow, L. H. Spragens, R. J. Stoeckle, L. C. Evertson, L. A. Jennings, and D. B. Reuben. 2020. Recommendations to improve payment policies for comprehensive dementia care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 68(11):2478–2485.

Lourida, I., R. A. Abbott, M. Rogers, I. A. Lang, K. Stein, B. Kent, and J. Thompson Coon. 2017. Dissemination and implementation research in dementia care: A systematic scoping review and evidence map. BMC Geriatrics 17(1):147.

Moberg, J., A. D. Oxman, S. Rosenbaum, H. J. Schünemann, G. Guyatt, S. Flottorp, C. Glenton, S. Lewin, A. Morelli, G. Rada, P. Alonso-Coello, E. Akl, M. Gulmezoglu, R. A. Mustafa, J. Singh, E. von Elm, J. Vogel, and J. Watine. 2018. The GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework for health system and public health decisions. Health Research Policy and Systems 16(1):45.

Murray, E., S. Treweek, C. Pope, A. MacFarlane, L. Ballini, C. Dowrick, T. Finch, A. Kennedy, F. Mair, C. O’Donnell, B. N. Ong, T. Rapley, A. Rogers, and C. May. 2010. Normalisation process theory: A framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Medicine 8(1):63.

NAE (National Academy of Engineering). 2011. Engineering a learning healthcare system: A look at the future: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Families caring for an aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NIA (National Institute on Aging). 2018. Stage model for behavioral intervention development. https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/dbsr/nih-stage-model-behavioral-intervention-development (accessed August 18, 2020).

NQF (National Quality Forum). 2016. Quality in home and community-based services to support community living: Addressing gaps in performance measurement. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum.

Petticrew, M., C. Knai, J. Thomas, E. A. Rehfuess, J. Noyes, A. Gerhardus, J. M. Grimshaw, H. Rutter, and E. McGill. 2019. Implications of a complexity perspective for systematic reviews and guideline development in health decision making. BMJ Global Health 4(Suppl 1):e000899.

Proctor, E., H. Silmere, R. Raghavan, P. Hovmand, G. Aarons, A. Bunger, R. Griffey, and M. Hensley. 2011. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 38(2):65–76.

Rogers, E. M. 2003. Diffusion of innovations, 5th ed. New York: Free Press.

Rutter, H., N. Savona, K. Glonti, J. Bibby, S. Cummins, D. T. Finegood, F. Greaves, L. Harper, P. Hawe, L. Moore, M. Petticrew, E. Rehfuess, A. Shiell, J. Thomas, and M. White. 2017. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. The Lancet 390(10112):2602–2604.

Sohn, H., A. Tucker, O. Ferguson, I. Gomes, and D. Dowdy. 2020. Costing the implementation of public health interventions in resource-limited settings: A conceptual framework. Implementation Science 15(1):86.

Teisberg, E., S. Wallace, and S. O’Hara. 2020. Defining and implementing value-based health care: A strategic framework. Academic Medicine 95(5).

The Lewin Group. 2018. Final evaluation report: Testing experience and functional tools in home and community-based services demonstration program. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2019-12/teft-evaluationfinal-report.pdf (accessed January 21, 2021).

University of Washington. 2020. What is implementation science? https://impsciuw.org/implementation-science/learn/implementation-science-overview (accessed September 8, 2020).

Unützer, J., A. C. Carlo, R. Arao, M. Vredevoogd, J. Fortney, D. Powers, and J. Russo. 2020. Variation in the effectiveness of collaborative care for depression: Does it matter where you get your care? Health Affairs 39(11):1943–1950.

Walugembe, D. R., S. Sibbald, M. J. Le Ber, and A. Kothari. 2019. Sustainability of public health interventions: Where are the gaps? Health Research Policy and Systems 17(1):8.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2004. Monitoring and evaluation toolkit: HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/a85537/en (accessed January 21, 2021).

Woltmann, E. M., R. Whitley, G. J. McHugo, M. Brunette, W. C. Torrey, L. Coots, D. Lynde, and R. E. Drake. 2008. The role of staff turnover in the implementation of evidence-based practices in mental health care. Psychiatric Services 59(7):732–737.

This page intentionally left blank.