2

Evaluating Outcomes Based on Thoughtful Program Designs (Step 5)

HIGHLIGHTS1

- Faculty development is a knowledge translation activity. (Artino and Thomas)

- Using a framework can help guide the design, implementation, and evaluation of faculty development programs. (Thomas)

- There are limitations to using self-reported satisfaction surveys as evaluation tools. (Artino)

STARTING WITH THE END IN MIND: DESIGNING AND EVALUATING FACULTY DEVELOPMENT

Anthony Artino, The George Washington University, and Aliki Thomas, McGill University

Beginning with the end in mind, said Anthony Artino, tenured professor at The George Washington University, the fifth step of designing and evaluating faculty development becomes the first step. Faculty is defined broadly, said Artino, to include anyone who is involved with the education and training of health professionals, including professors, clinical teachers, and others. Artino’s opening remarks drew comments in the chat box throughout

___________________

1 This list at the beginning of each chapter is the rapporteurs’ summary of the main points made by individual speakers (noted in parentheses). The statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

the presentation and while he and Aliki Thomas, associate professor at McGill University, described a case example to illuminate their points (see Box 2-1) throughout the presentation, which was divided into three topics:

- Faculty development as a knowledge translation (KT) activity

- Using a framework to guide design

- Evaluation and sustainability

Faculty Development as a Knowledge Translation Activity

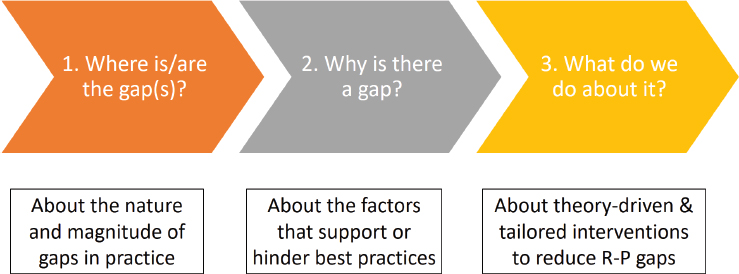

As part of best practices in virtual education, Thomas began by asking the workshop participants to complete the poll, “Is faculty development a knowledge translation intervention?” While many responded “yes,” quite a few respondents indicated they were not sure what KT was. KT, said Thomas, is a process that aims to optimize the uptake of knowledge and scientific evidence to improve educational practices and policies (Thomas et al., 2014). Faculty development can be considered a KT activity because the goal is to increase or change the faculty’s knowledge, skills, attitudes, and practices, with the ultimate goal of improving learner outcomes and eventually patient care. KT is divided into three steps, said Thomas (see Figure 2-1). The first step is identifying the research to practice (R-P) gap: what is the magnitude and nature of the gap between current practices and best practices in the literature? The second step is finding out why there is a gap: what are the factors that support or hinder the uptake of that

SOURCES: Presented by Artino and Thomas, August 11, 2020. Data from Thomas and Bussières, 2016b.

evidence? Finally, the third step is determining what to do, using theory-driven and tailored interventions to reduce the gap.

In response to a workshop participant question, Thomas clarified that the term knowledge translation is an umbrella term. KT is a process used to address knowledge, skills, attitudes, behaviors, and other constructs, if they are the causes of the R-P gap, with the penultimate goal of promoting use of best practices. A gap between current practices and best practices might be due to a lack of knowledge, a lack of skills, or a specific attitude, she said. Once the reason for the gap is identified, the intervention would focus on making changes in that area. Thomas noted that in “knowledge translation” there are more than 100 different terms used to refer to the same process and that often terms such as research use, diffusion, dissemination, and implementation are used interchangeably although they mean different things. In the chat box, Warren Newton, president and chief executive officer for the American Board of Family Medicine, worried about knowledge being presented as binary or gaps, as opposed to higher-order “wisdom.” Getting facts seems a low bar when compared to demonstrating implementation and critical skills. Artino agreed saying, “Education is about preparing participants for yet-to-be experienced problems.” Sherman expounded on the idea suggesting faculty development be viewed as continuing professional development where there is ongoing assessment of the needs of the faculty, both as a group and as individuals.

Using a Framework to Guide Design

Changing behavior is a complex process, said Thomas, and faculty behavior takes place in complex clinical and educational environments. Using

theories and frameworks can help to guide implementation efforts aimed at modifying behaviors. Implementation science is the scientific study of KT, said Thomas, and offers theories, models, and methods. Frameworks can help explain and predict the intended change and identify the multiple factors that can increase or decrease the likelihood that the change will occur. Furthermore, the use of a framework that considers different stakeholders emphasizes the notion that action plans should take into account the perspectives of all those who will be involved in and affected by the proposed change in behavior; such a framework also addresses issues of inclusion and diversity. There are multiple types of theories, models, and frameworks that can guide the design and evaluation of faculty development programs, including models that describe the process of translating research into practice, theories to explain what influences the outcomes, and frameworks to evaluate implementation.

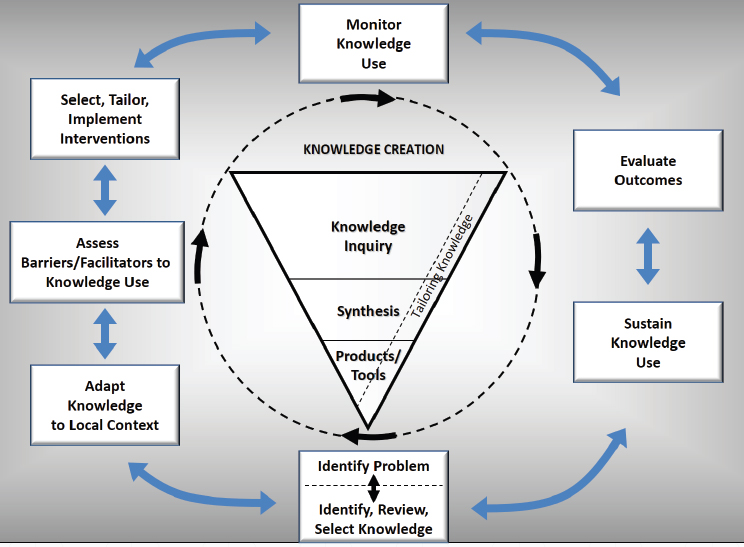

Thomas presented a conceptual framework called the knowledge-to-action framework, which is based on a review of more than 30 planned-action theories (Graham et al., 2006) (see Figure 2-2). The knowledge-to-action framework takes local context and culture into account and offers a holistic

SOURCES: Presented by Thomas, August 11, 2020. Data from Thomas and Bussières, 2016a.

view of the KT phenomenon. The framework considers how stakeholders will respond to anticipated changes and how change agents can facilitate the changes in educational practice. The funnel in the middle of the framework, said Thomas, represents the creation of knowledge from research findings and outcome evaluations that will be translated to the users. As the funnel becomes smaller, the knowledge becomes more synthesized and potentially more useful to the end users. The seven steps surrounding the funnel, while sequential in theory, might occur simultaneously, and there may be interactions between the steps as well as the knowledge base (e.g., if new evidence emerges). Thomas noted that the authors of the framework acknowledged that KT interventions rarely take place in environments where the knowledge gaps are clearly defined and where the actions required to change behavior are readily implementable and sustainable.

Looking at the framework with the aforementioned case example in mind (see Box 2-1), Thomas said the first step is identifying that the problem is “suboptimal feedback practices” in the teaching hospital. After identifying the problem, the literature is reviewed for evidence on strategies for giving effective feedback, and current feedback practices are examined in order to confirm the presence and nature of the gap between current practices and best practices. The second step is adapting the knowledge to the local context to ensure that it is relevant, applicable, and useful for the particular setting. At this step, said Thomas, it is critical to involve multiple stakeholders for their perspectives; in the case example, this could include teachers, learners, program directors, and curriculum chairs. The third step is assessing facilitators and barriers to knowledge use: what factors will make it more or less likely that feedback behavior will change? At this step, it is important to look at both individual and organizational facilitators and barriers (see Table 2-1).

TABLE 2-1 Some Individual and Organizational Facilitators and Barriers to Change

| Individual | Organizational | |

|---|---|---|

| Facilitators |

|

|

| Barriers |

|

|

SOURCE: Presented by Thomas, August 11, 2020.

A workshop participant used the chat box to ask about systemic barriers; for example, faculty may have the knowledge about appropriate feedback but may have problems implementing it because of difficulty reconciling their dual roles of teacher and clinician. To mitigate these issues, it is critical to get a variety of stakeholders, including faculty, leaders, and managers, involved in the process “from the get-go,” said Thomas. A participant shared her personal experience in the chat saying input from faculty is not widely sought for designing faculty development programs that truly address the needs of faculty. Bushardt responded, saying that this view “is not all that different from patients’ involvement (or lack thereof) across health care delivery, [but] that’s hopefully changing now with more focus on person-centered care paradigms.”

The fourth step is selecting, tailoring, and implementing the actual KT intervention, Thomas explained. At this step, the faculty development activity (as the KT intervention) is implemented to try to reduce the gap between current practices and best practices. For example, if the gap is a lack of knowledge on how to give effective feedback, the intervention could be giving faculty regularly scheduled, online opportunities to learn and to practice feedback. This step includes (1) considering who needs to do what differently and how, (2) the involvement of multiple stakeholders to promote uptake of new strategies, and (3) an examination of KT interventions in the literature. Thomas noted, in response to a participant’s question, that interventions should be chosen based on whether evidence in the literature supports use of the intervention. After the intervention is implemented, the fifth step is monitoring knowledge use. This could include looking for measurable changes in knowledge, attitudes, skills, and behaviors, such as increased knowledge about effective feedback or improved feedback practices.

Evaluation and Sustainability

The sixth step of the knowledge-to-action framework—and an essential part of any faculty development program—is evaluation. Artino defined evaluation as the “systematic acquisition and assessment of information to provide useful feedback about some object” (Trochim, 2006), and its goal is to “determine the merit or worth of some thing” (Cook, 2010). In the case of faculty development, the “object” or the “thing” being evaluated is the faculty development program. There are three reasons that one might conduct an evaluation, said Artino. The first is to be accountable for the time, money, and effort that have been invested in the faculty development program. The second is to generate understandings and new insights about what is working and what is not working. The third reason is to support and guide improvement of the faculty development program.

Evaluation is both similar to and different from research, said Artino. Research is broader, and is often aimed at discovering generalizable knowledge, understanding, or theory. However, many of the same precepts apply to both evaluation and research: both should ask relevant questions, be rigorous, use appropriate methods, adhere to ethical principles, and report and disseminate findings. Artino noted that dissemination does not have to be national or international; local dissemination to key stakeholders is relevant and important. One key difference between evaluation and research, said Artino, is that evaluation is often situated in a “potentially sensitive political and ethical context” with many different stakeholders, including policy makers, funders, regulators, teachers, and students. When considering evaluation, it is helpful to consider the different perspectives and goals of these stakeholders, he said.

Even after evaluation of a faculty development program, said Thomas, there is one more step. It is essential to ensure the sustainability of knowledge; that is, to ensure that the changes in knowledge or behavior last past the “honeymoon period” of a month or two. One strategy for sustainability is having a “champion” on site, who can hold regular meetings with the team, have regular check-ins with team members, and ensures that the program remains a priority.

What and How to Evaluate

Evaluation is often framed as a way to answer the question “Does the faculty development program work?” However, said Artino, framing it in this way suggests a quasi-experimental design that looks for a clear, linear relationship between the program and changes in attitudes, learning, and behavior. Instead, he said, it may be more helpful to consider the question, “Why does the faculty development program work (or not), for whom, and under what circumstances?” While this framing is more complex and requires evaluating multiple constructs, it invites a nuanced, mixed methods, holistic approach to evaluation. A program evaluation might look at both proximal and distal constructs, said Thomas. A proximal construct would be, for example, changes in the feedback practices of a particular teacher. A distal construct could be the knowledge of the learner, and ultimately his or her performance as a health care professional. This type of construct, while more important in the long run, is more difficult to measure. To select relevant and feasible constructs for evaluation, said Thomas, it is essential to have multiple stakeholders at the table to lend their perspectives.

In the case example, said Thomas, one could measure outcomes such as the number of learners receiving appropriate feedback, the nature and frequency of feedback, or teachers’ and students’ self-reported experience of the feedback interaction. Measuring these types of outcomes can be done

with a variety of methods (see Table 2-2). Surveys and questionnaires are common ways to measure knowledge, attitudes, practices, and self-efficacy, while observation can be an effective way to measure actual practice and competence. Ideally, said Artino, multiple evaluation methods would be combined to gather the most robust evidence about outcomes. One method that is frequently used for evaluation is the “butts-in-seats” measure, which simply reports the number of people trained or educated. This measure, Artino said, is like “evaluating how you did in a battle by how many bullets you used.” The number of program participants is a useful starting point but cannot be the end of the evaluation.

Using Surveys for Evaluation

A method that is frequently used to evaluate faculty development or other educational programs is a self-reported survey of satisfaction, also called a “smile sheet,” said Artino. Workshop participants were polled on whether smile sheets are a good way to collect outcome data for evaluation purposes; while many said yes, more replied no. Artino said that the literature on this issue is a bit “all over the map,” but that the most recent literature suggests that satisfaction surveys are a poor way to evaluate learning outcomes. A recent meta-analysis (Uttl et al., 2017) looked at 51 published studies on satisfaction surveys, and found that satisfaction ratings are “essentially unrelated to learning.” In other words, said Artino, being satisfied with the course is usually unrelated to how much was learned in the course.

Another study found that providing participants with cookies at the end of a course session could create statistically significant and very large increases in the ratings of the course, course materials, and teachers (Hessler et al., 2018). In addition, satisfaction surveys have been shown to be biased against a number of groups, including women, minorities, and short people,

TABLE 2-2 Examples of Various Methods for Measuring Outcomes

| Construct | Method |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | Survey, vignette, test |

| Attitudes | Survey, standardized questionnaire, interviews |

| Self-reported practices | Survey, standardized questionnaire, interviews |

| Self-efficacy | Survey, standardized questionnaire, interviews |

| Actual practice | Observation, chart audit, video recall |

| Competence | Simulation, vignettes, observation, videoconference |

SOURCE: Presented by Artino, August 11, 2020.

said Artino. A workshop participant asked how to mitigate this type of bias, and Artino responded that even with a high-quality, well-written satisfaction survey, bias will likely still exist. He encouraged people to focus on measuring the specific skills, knowledge, and behaviors that the activity is designed to change, rather than measuring satisfaction with the course or the instructor.

The crucial message, said Artino, is that smile sheets are of limited value, and rigorous evaluation of faculty development needs to use other methods. However, he said, surveys can still provide valuable evaluation data if they are well designed, linked to theory or a framework, and focused on constructs beyond satisfaction. For example, surveys can be used to measure outcomes such as self-reported knowledge, attitudes, or practice patterns. He noted that the literature is replete with examples of validated surveys that measure these types of constructs, so there is no need to “reinvent the wheel.” Even when validated, surveys should be reviewed with an eye toward how they will function in the particular setting and population, and they should always be pretested before using.

REFERENCES

Cook, D. A. 2010. Twelve tips for evaluating educational programs. Medical Teacher 32(4):296–301. doi: 10.3109/01421590903480121.

Graham, I. D., J. Logan, M. B. Harrison, S. E. Straus, J. Tetroe, W. Caswell, and N. Robinson. 2006. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education for Health Professionals 26:13–24.

Hessler, M., D. M. Pöpping, H. Hollstein, H. Ohlenburg, P. H. Arnemann, C. Massoth, L. M. Seidel, A. Zarbock, and M. Wenk. 2018. Availability of cookies during an academic course session affects evaluation of teaching. Medical Education 52:1064–1072.

Thomas, A., and A. Bussières. 2016a. Knowledge translation and implementation science in health professions education: Time for clarity? Academic Medicine 91(12):e20. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001396.

Thomas, A., and A. Bussières. 2016b. Towards a greater understanding of implementation science in health professions education. Academic Medicine 91(12):e19. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001441.

Thomas, A., A. Menon, J. Boruff, A. M. Rodriguez, and S. Ahmed. 2014. Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: A scoping review. Implementation Science 9:54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-54.

Trochim, W. M. K. 2006. Evaluation research. http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/evaluation.php (accessed December 15, 2020).

Uttl, B., C. White, and D. Gonzalez. 2017. Meta-analysis of faculty’s teaching effectiveness: Student evaluation of teaching ratings and student learning are not related. Studies in Educational Evaluation 54:22–24.

This page intentionally left blank.